How does the Western world intertwine with the nomadic lifestyle? How do folk traditions rooted in closeness to nature transform our relationship to sustainability and development? Réka Neszmélyi and Balázs Máté gained valuable experience in Mongolia on such and similar issues: their impressions are now captured in a zine. Let’s have a look!

Réka Neszmélyi and Balázs Máté started their exploration in Mongolia in 2019, where they spent two months. Since they both work as freelancers—Réka as a graphic designer and Balázs as a photographer—they feel the need to put aside their work from time to time and move into a completely new environment, even if it is a difficult road. Réka says there are personal reasons behind their choice of destination. “When I was a child, my father traveled to Germany a lot as a musician, and once when he returned home, he brought me a photo album as a gift, which presented the culture of distant peoples. For some reason, I was absolutely fascinated by the Mongolian landscape already at that point and from then on it was clear that I would like to go there someday,” she said enthusiastically.

The creative duo wanted to learn about the Mongol nomadic culture, so they contacted several locals with the help of a Hungarian-Mongolian friend before the trip, so that by the time they arrived, they could get a glimpse of this unique world through acquaintances. Since Balázs had already started longer journeys by train or hitchhiking, they decided to take the Trans-Siberian Railway line to the Mongolian capital, Ulaanbaatar. “The trip eventually took two weeks, because we got off at a few places in Ukraine and Siberia on the way, such as the unimaginably huge Lake Baikal. By the way, if you want to go without interruption, you have eight days of train ride waiting for you,” Balázs detailed.

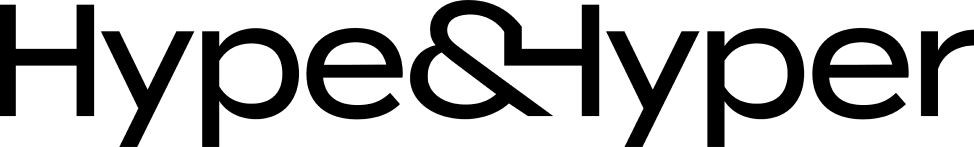

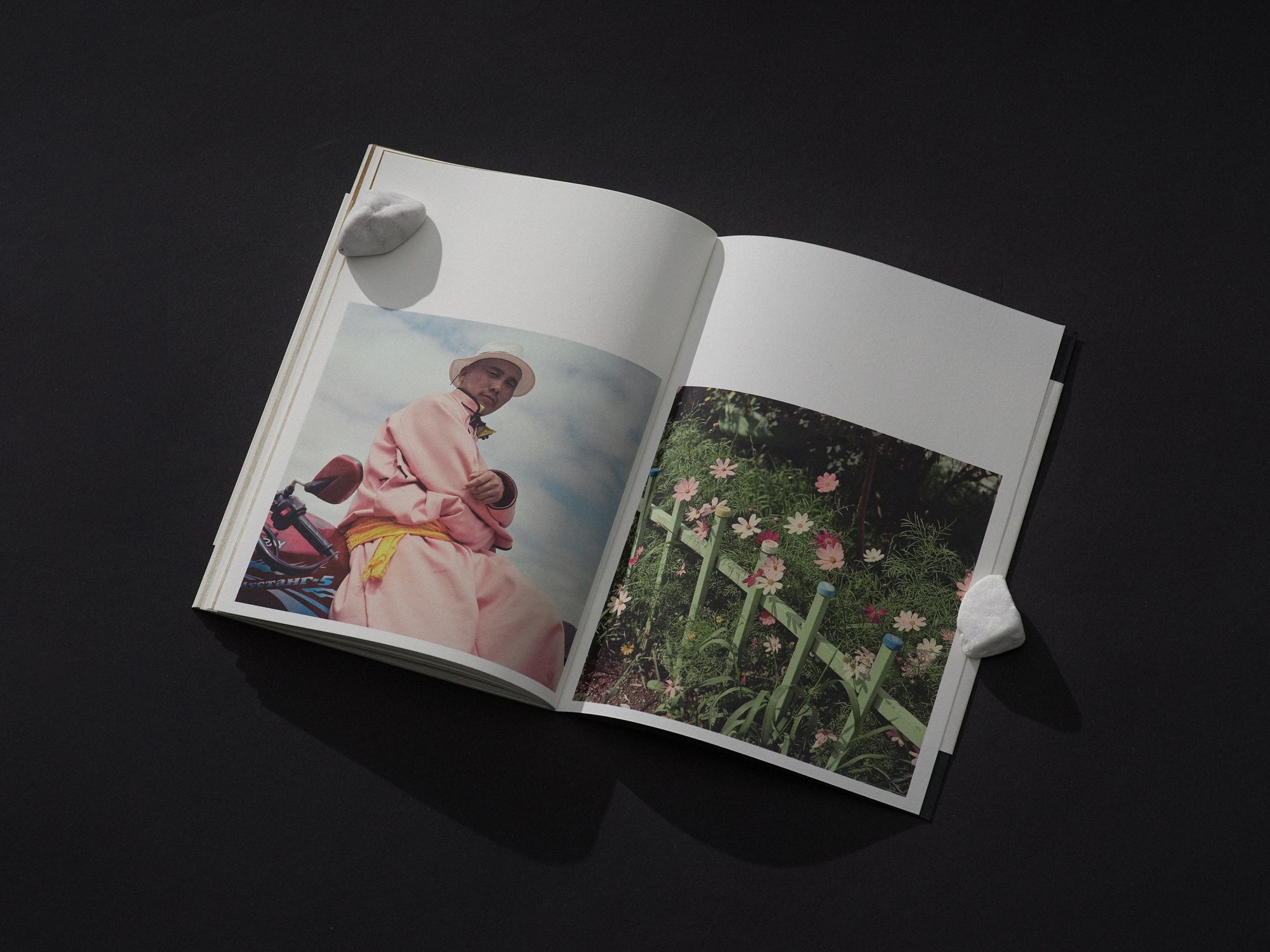

When they arrived, they didn’t have a clear idea of what they wanted to create from the photographs.

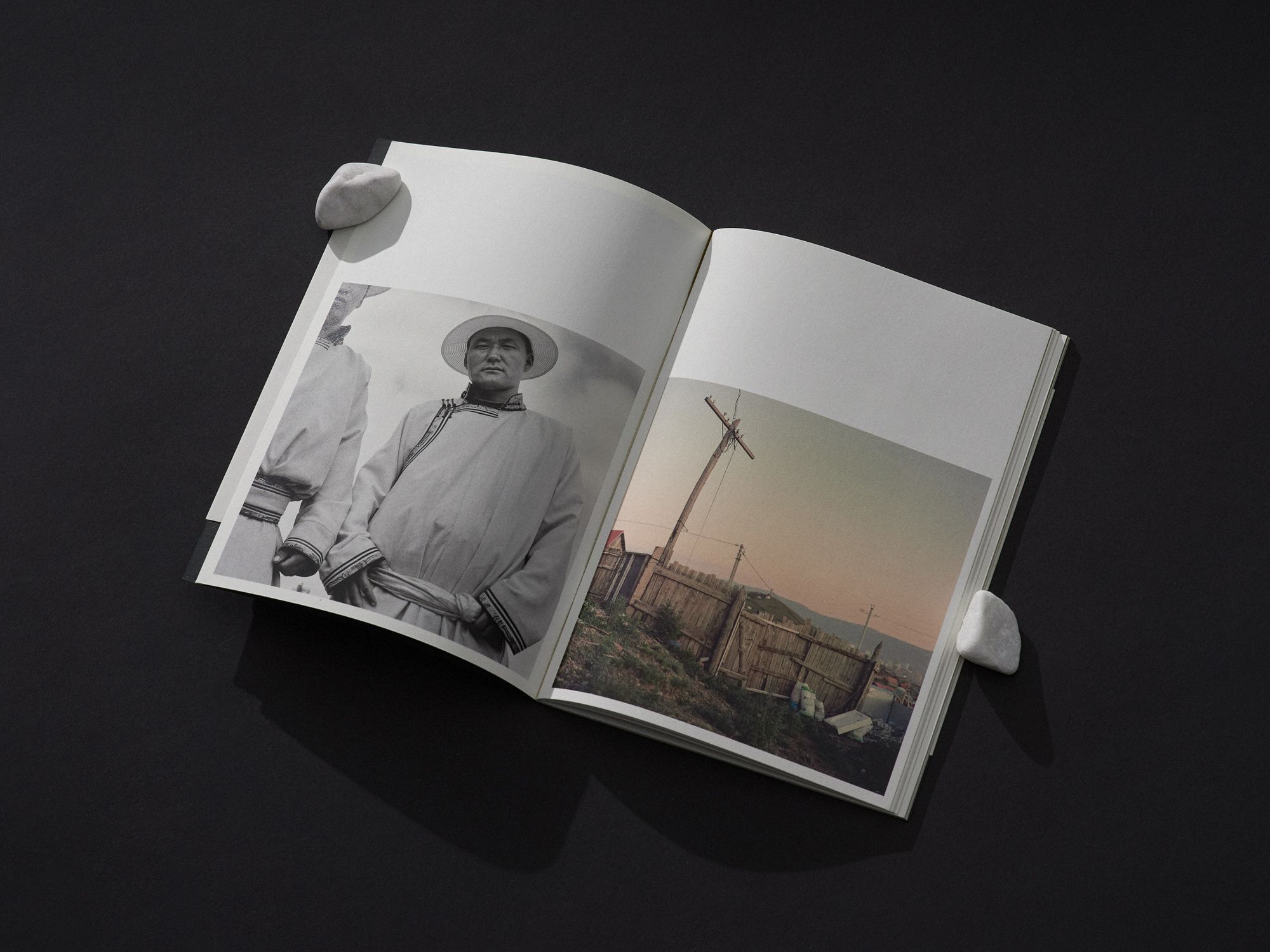

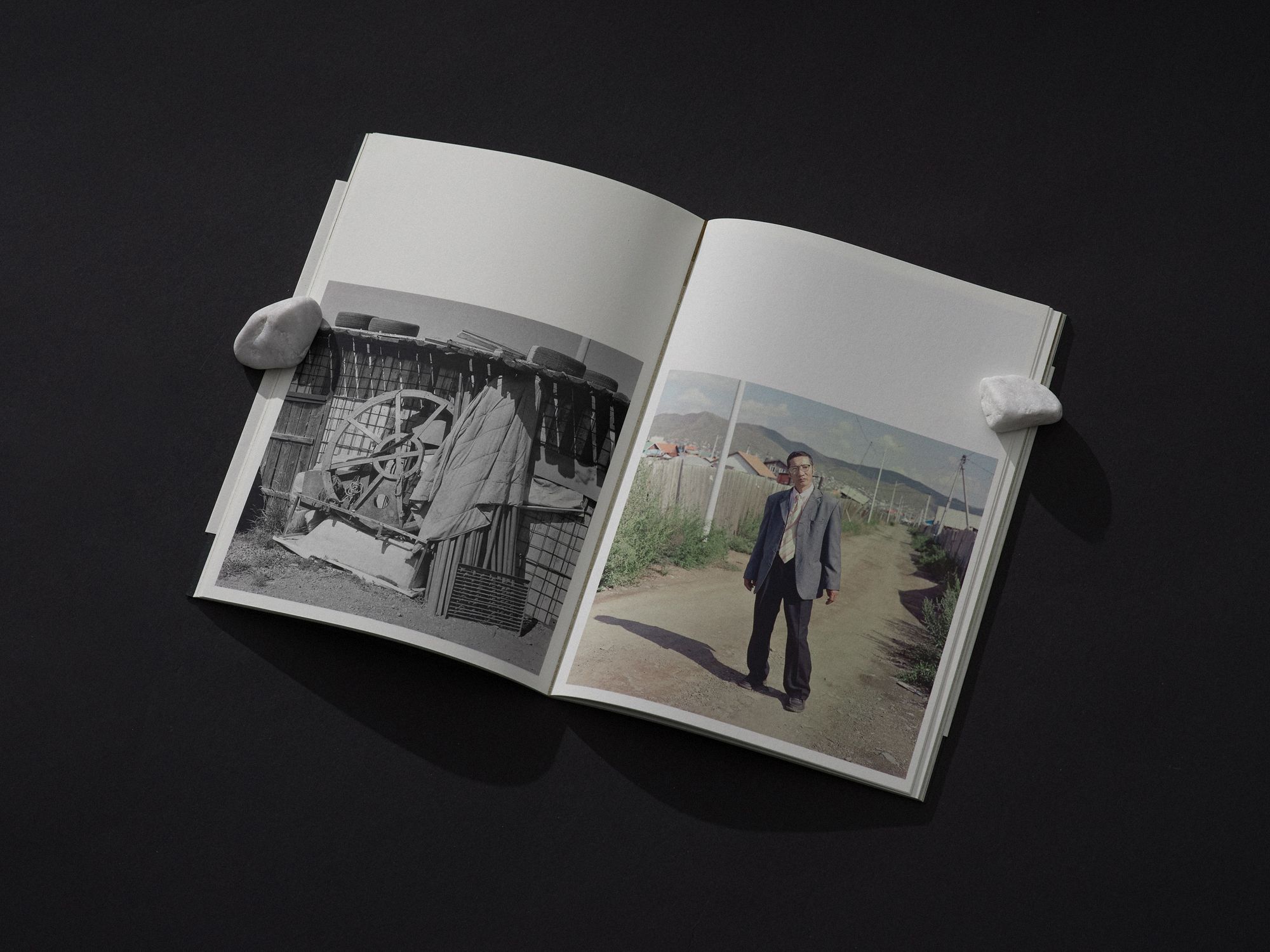

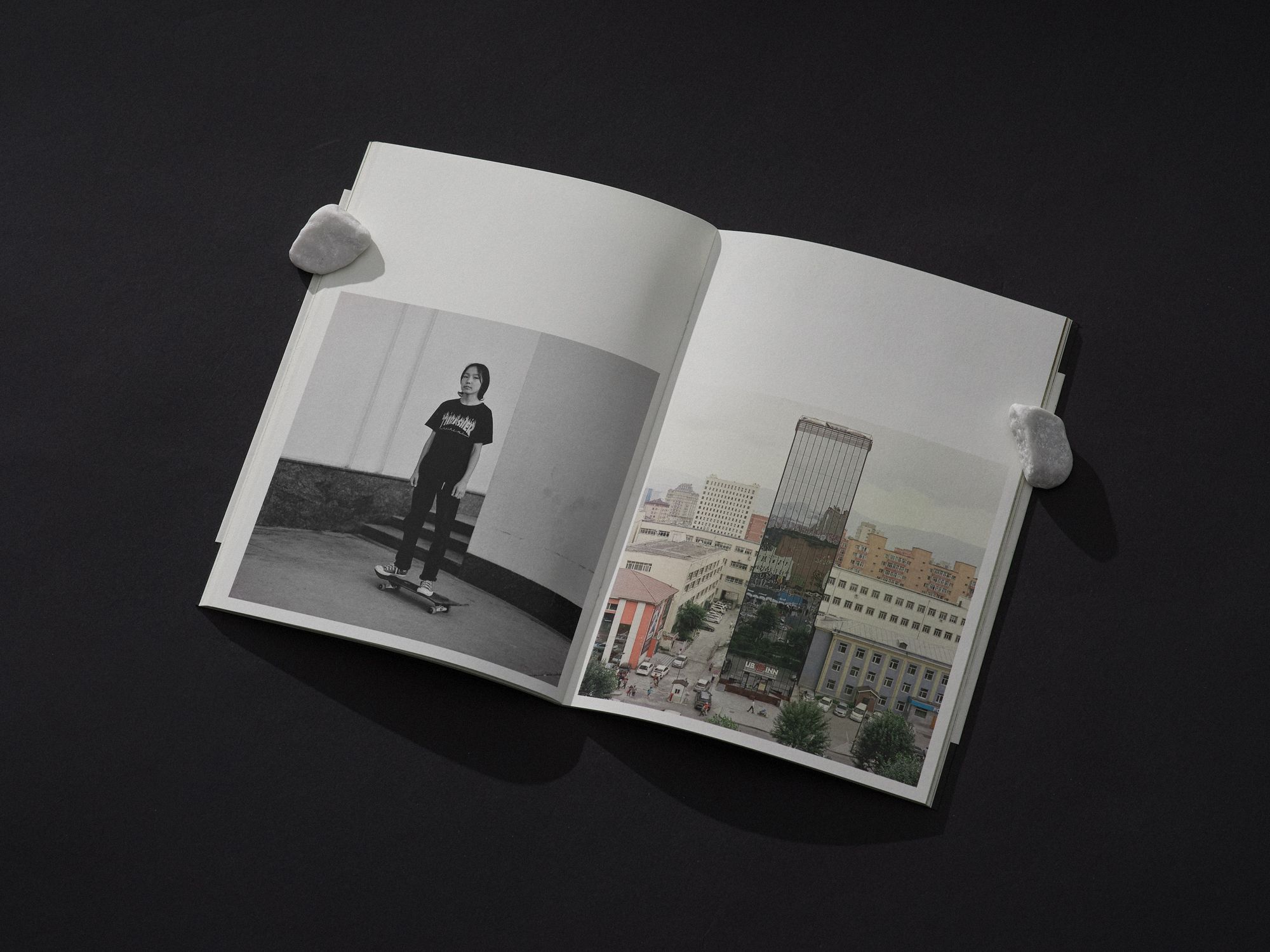

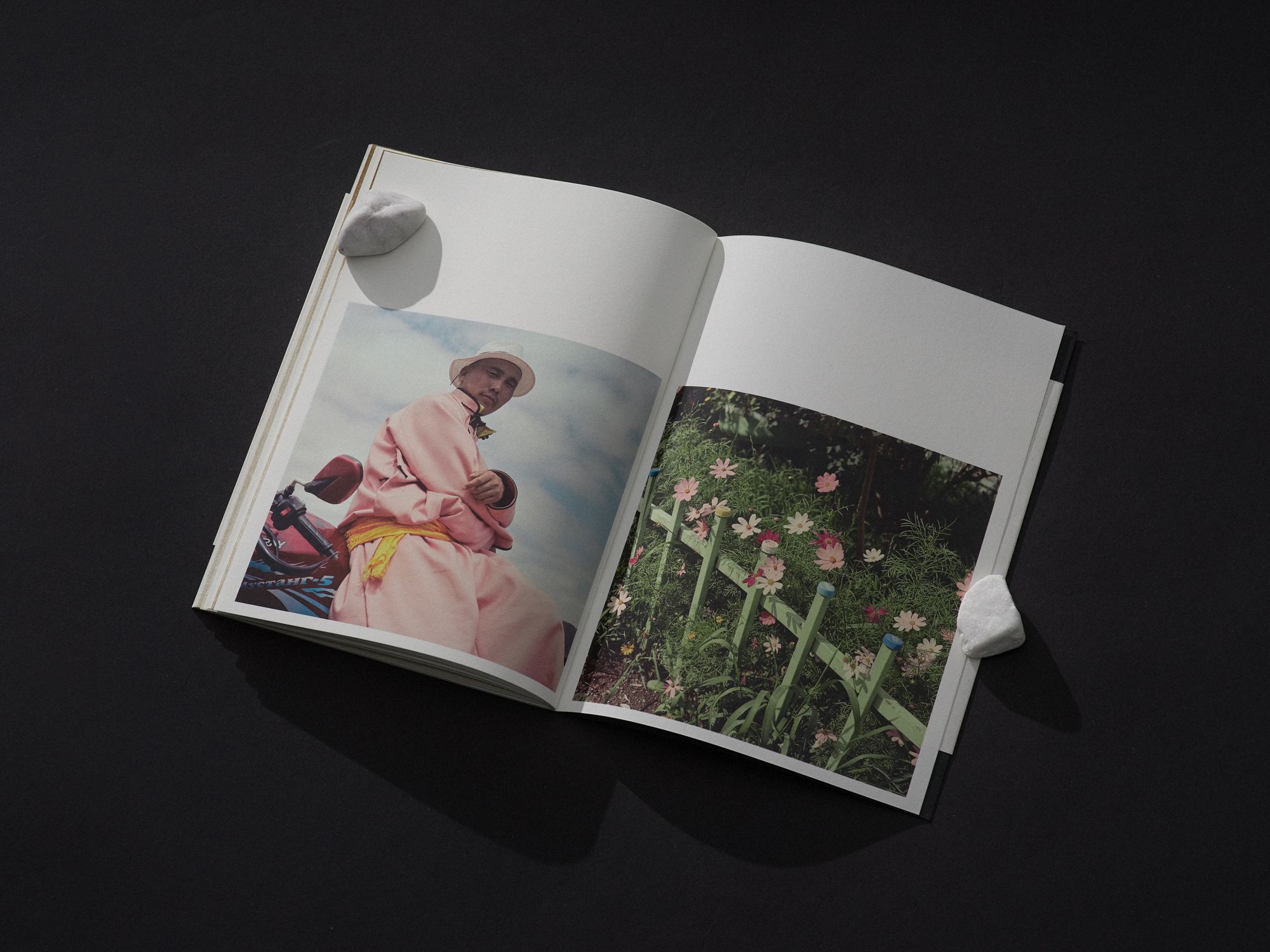

“I had a camera, so I started taking pictures without any special organizing principles. I think this is also apparent on the material: the finished zine is not a strongly conceptual work, but rather a series of impressions about a journey that remains from a short but intensive encounter with a culture that is distant for us,” Balázs pointed out.

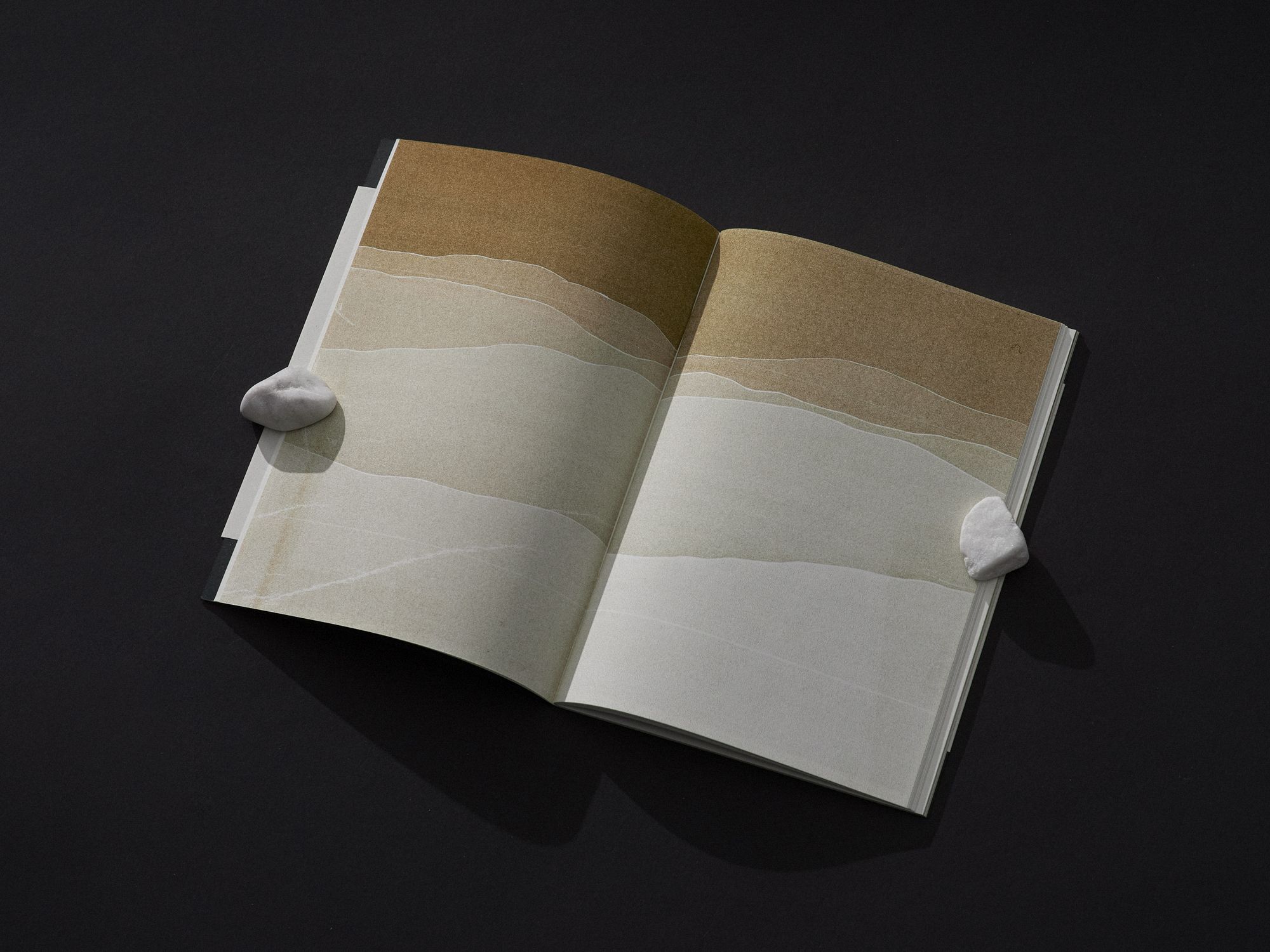

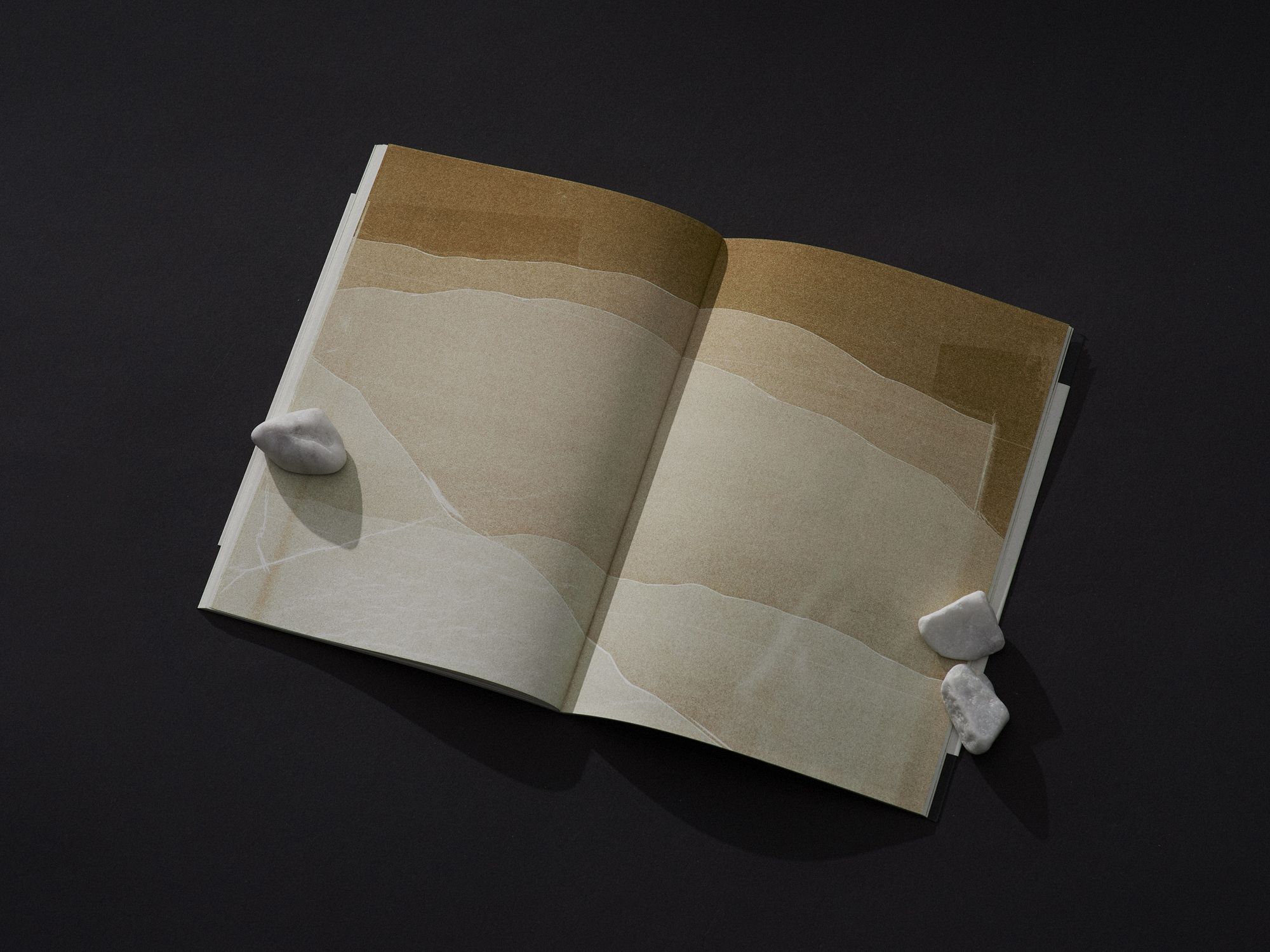

As both Réka and Balázs said, they were inspired not only by the society and the people but also by the landscape itself, the endless steppe and the fact that in Mongolia, the nomadic culture has made the land belong to everyone. “Almost nothing is private property, especially in the countryside: those who travel there will not really encounter fences or signs marked as private property,” Balázs added. “Another fundamental experience is that since there are no forests on the steppe, you travel in a completely different way: the landscape is like a big grassy sea, with mountains and hills. If I spot something in the distance that interests me, I’ll just go there, straight ahead. This wavy freedom of the landscape later inspired the riso prints in the zine, which are essentially collages designed to evoke the steppe,” he continued.

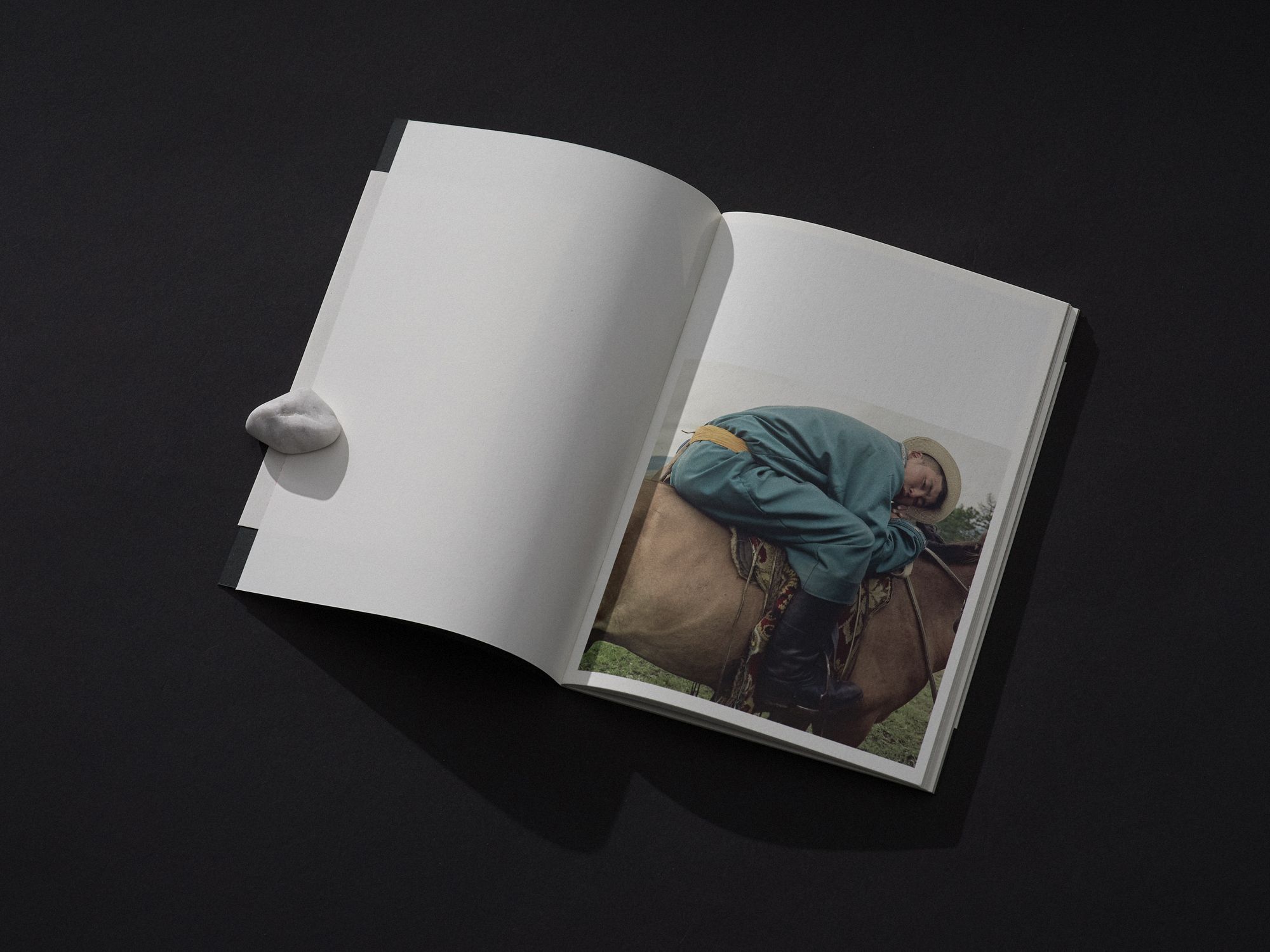

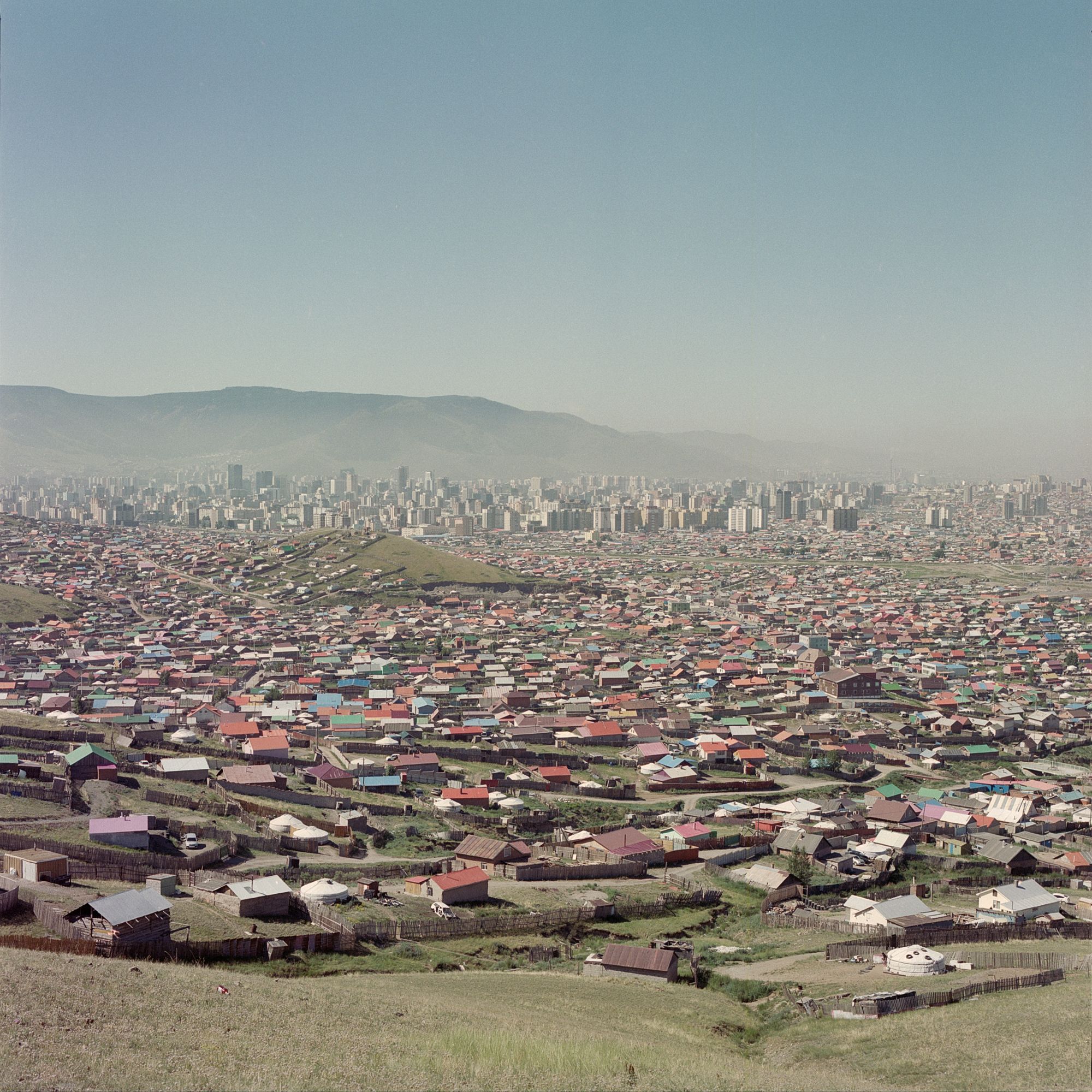

In the publication, which comes to life even as a visual diary, the contrast between the nomadic lifestyle and the metropolitan and western life is emphasized. The latter takes the lead at a rapid pace against the former: with some sixty-eight thousand Mongolians leaving nomadism and moving to the city every year. As the artist duo said, there are several reasons for this, including climate change, which makes summers more and more scorching, and winters devastatingly freezing. Thus, on the morning after a frosty night, the animals of the nomads may die, and then they must leave for the city on the same day.

This particular, momentary world is foreshadowed in the text that accompanies the cover of the publication, referring to both the vulnerability and the value of the nomadic life. “Nomad families move twice a year: they have a summer and a winter shelter. They pack up all their belongings and migrate with the animals to their seasonal place. Such a move leaves a mark on the landscape: a well-trodden circle, and a surrounding patch that has been trampled by the flock, that’s all that remains. No foundations, no fences, no pens. This kind of presence is modest and cooperative. That’s what we can call sustainable. Compared to this, the slogans in today’s Western culture seem deeply cynical to me,” Réka said.

We were also curious about the personal stories behind the photographs in this highly visual publication: Réka and Balázs shared some of these snapshots with us.

“Something that often comes to my mind is a family photo from the beginning of the trip. In the book, there is a cityscape, which was taken in one of the yurt boroughs surrounding Ulaanbaatar. These are the ever-expanding rings of yurts around the city, made up of families who have abandoned nomadism, either deliberately or by necessity. It’s like a huge harbor with ships that will probably never move again. There was also a yurt where we lived for a week with a family of three children: this was the first such living space we had ever entered. Apart from us, there was another guest living there, so there were eight of us living in a circular area about eight meters in diameter. One night, when we were all at home and everybody was doing something, I just saw the situation from the outside. Suddenly, I could feel that even without walls, everyone could give space to each other: the mother was preparing for dinner, the father was practicing from a dictionary with the other guest, and one of the older girls started practicing a dance that she had learned at school that day. Everyone was able to be present in their own intimate moments. Before the trip, it was inconceivable to me how an entire family could live together in a yurt,” Réka said.

“At one of the families that hosted us, we took a picture of a little blue truck and the meat drying on it. The air in the country is very dry, so it is easy to preserve food this way, they don’t spoil. One day Sukhbaatar asked me to get on the bike behind him, and then we drove off in this direction. We moved away from the yurt for about half an hour when about 400 sheep and goats of the family finally appeared behind one of the hills. Sukhbaatar picked up some small pebbles from the ground and threw them around to show me how to shepherd the herd and pointed in the direction we came from. Then he smiled and patted me on the shoulder, got on the bike and drove away. Anyone who knows me knows that I get lost easily in Budapest, so it was exciting, but I finally found my way back to our accommodation,” Balázs shared.

Another special feature of the photographs in the zine is that they were all shot on film, so the creative couple could only view the pictures after they arrived home. “The lack of instant feedback was a very nice and exciting process, which completely changes the way people take pictures,” Balázs said.

You can find Réka Neszmélyi and Balázs Máté’s own photo book on the shelves of ISBN Books+Gallery, Mai Manó House and the Írók Boltja.

Réka Neszmélyi | Behance | Instagram

Balázs Máté | Instagram

Taste manipulation by touch, or tactility in gastronomy

Where it all began | We visited Silicon Valley