The only constant in a city is change. This is especially true for public urban development projects in which the different layers of society meet the developer’s vision and its realisation in a complex way. In our article, we investigate two exemplary cases of this complex phenomenon. In the planned comprehensive alteration of Nyugati Railway Station—or Nyugati for short—and its surroundings, besides traffic organisation, the focus is on the community, while in the case of Városháza Park, questions about how our capital is represented arise while searching for the latest solutions in architectural design.

This article was published in print in Hype&Hyper 2022/2.

Author: Géza Kulcsár

Many experts on urbanism—like the amazing Kevin Lynch in his work titled The Image of the City—have explained that the essence of a public space unfolds in time. This means that while there are—besides architecture—many different engineering, design, and theoretical disciplines taking part in dividing up public spaces and assigning functions to their individual parts, the goal is always in creating a static unity, therefore an urban space born this way can only live while in motion. What’s more, even this urban time perception needs to be understood in two ways: it concerns those who experience and use these urban spaces as well as—and this aspect is the focus of our article—the life of the city itself, its constant evolution, and its continuous rebirth according to the different eras, needs, materials and technologies at play.

This duality—creation and the concept of being created or plannability and spontaneous change over time—is what we’re interested in when talking about urban development or more precisely, the transformation of our public spaces. It’s obvious that social movements, a long line of surpluses and deficits lead to the decision of interfering with an area in the city, similarly, as the effectiveness of the interference is something time will tell according to the tangible experiences, old and new habits of those living in the city. The plans, however, still stand in front of us like visions of the future, bounded by space, but still eternal and universal.

Since its opening in 1877, Nyugati Railway Station and its surroundings are not only a practical area from where you can travel and to where you can arrive, but more: the totality of different experiences, emotions, impressions, and notions—something that is true for most urban spaces, however, areas of transit usually unify these features more than others. The building of Nyugati was born from the philosophy that almost predestines the structure for its cognitive role: the ethereal, steel structure prompted by trends in the Great Exhibitions and industrialisation—such as the Crystal Palace from the first Great Exhibition in 1851 or Nyugati’s architectural sibling, the Eiffel Tower—not only emphasises humanity’s faith in technological advancement, but also—at least according to the initial intentions—, creates an open and welcoming space. (If you are interested in the background of this approach, you can find theoretical and practical details in Douglas Murphy’s book, Last Futures: Nature, Technology and the End of Architecture.)

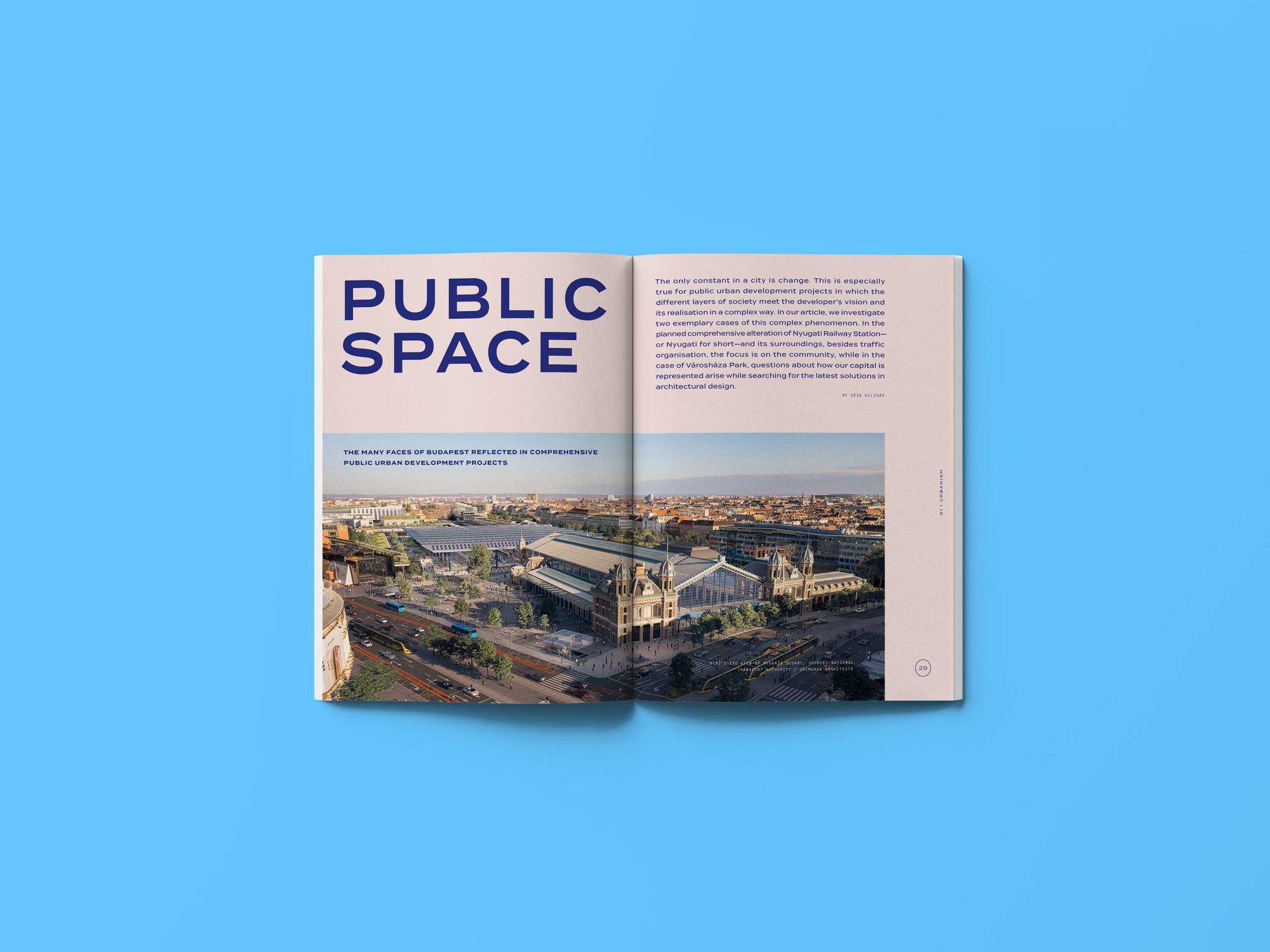

The plan of Grimshaw Architects, winning the open tender that takes into account the current guidelines for design and utilising space, as well as technological developments of the last 150 years, passes this intellectual heritage on, embedding it into a complex concept that extends and reimagines the railway station—similar to the firm’s already realised projects in London in which the Victorian spaces aesthetically resonate well with Nyugati’s space. But let’s stay for a moment with the centre of the new urban space: the station building that while staying structurally intact, in regard to its function it has been entirely reinvented—the platforms of the terminal station will be taken underground, meaning that the main hall contrary to standard practice—even on an international scale—of functioning as a multiple-purpose space, is reimagined to fulfil its function and become a welcoming, central community area. The underground railway tracks, of course, open up a whole new array for possibilities: while allowing for more trains coming in from the urban agglomeration, it also serves as a baseline for the next ambitious phase of rethinking the mobility of Budapest: creating a tunnel between Nyugati and Kelenföld railway stations. However, the question arises: can a railway station hall not receiving trains anymore retain its original identity? Even though the architecture of community and shopping spaces is reminiscent of the steel frame structure of railway stations and other industrial-functional spaces, it’s the sensory experiences of travelling by train—how it rattles on the tracks, or the sound of whistle blown as the train leaves the platform, and the image of people saying their goodbyes—that makes it what it is.

At the time when Nyugati was constructed, architects designed spaces with clear boundaries, while today city-wide planning is defined by networks—spaces and people dynamically moving together and opening up to each other. According to the plans, Nyugati is going to be turned into a car-free zone that’s essentially the natural, open-air extension of the railway station’s renewed spirit. While on this bustling side tightly woven into the urban fabric is still all about transit, the brownfield site in the back will also be renovated in the spirit of leisure time and relaxation in the form of a modern park that serves every layer of society. All in all, the ambitious plan represents an intellectually unified transition that changes the space and function to put motion and rest, work and leisure time into focus while respecting our old-new friend, Nyugati.

The rehabilitation of the space behind the station not only answers the age-old question of how public spaces should be utilised, but is also connected in many ways to another very current and exciting change in the city whose tender recently closed: the Városháza Park. Just like in the case of Nyugati, in this development plan, traditional European views and perceptions of space clash with modern community principles and technological opportunities. The idea is to create a park that—similarly to many representative European examples—positions the space expanding to Károly körút on the side of Városháza’s facade as a kind of hall for the building: a public space in the best possible sense. This approach makes the ideological and practical questions of design increasingly exciting since, besides the above-mentioned aspects of community and the usage of space, another big question needs to be answered: what is a city? How is it represented and by whom?

The winning design of the tender by Lépték-Terv Tájépítész Iroda in collaboration with Sporaarchitects answers this age-old question with one of the most universal symbols that is both evident and multifaceted just like a community: the circle. It protects, marks, and welcomes while organising the different goals, layers, and individuals present in the space into a system.

This thoughtful gesture, however, won’t ease the tensions surrounding the discussion of how to use social spaces. Architect at Mókembé, Ákos Takács, who likes dealing with theoretical debates, told us a bit more about this question. He was not only part of the team ranking a shared third place in the tender (with Áron Baki, Máté Gadolla, Márton Kőműves, Veronika Pápai, and Zsófia Csomay), but also researched the critical-speculative aspects of the utilisation of the space behind Nyugati Railway Station in his degree theses. The key to their development plan, tellingly named Janus, lies in emphasising the multifaceted yet controversial relationship between public space and community space that can be best illustrated by the traditional definition of the forum in urban architecture. “The space of the forum can be imagined as the container of rituals of democratic social life and its collective gestures. A dynamically designed, paved surface marks the boundaries of this collective living room’s action space as a magic carpet. Its abstract, simple, and generous design creates an opportunity for the space to be filled with new experiences every time by the residents, visitors, communities, and institutions utilising it. Instead of overcomplicated architectural and design gymnastics, the focus is on the diversity of being a multipurpose area. Space is not an icon in itself, rather a surface on which the energetic life of the community can be painted.”

We’ve seen how the relationship between a space and the community is not as evident and easily digestible as keywords want us to believe. But maybe this is exactly what gives real value to urban development projects since they provide an opportunity to have a discussion about our shared spaces and in essence, about ourselves—as this is what truly makes a city a city.

Prefer to read it in print? Order the fourth issue of Hype&Hyper magazine from our online Store!

One day with Martin Žák in Prague

Success requires a new and distinctive design