The preservation of pre-digital typefaces has gained momentum over the past quarter of a century, and in the last few years more and more type revival typefaces have been born in the region. Why did the practice become popular, and what benefits can a well-done type revival project bring to the graphic design scene or to the everyday user? We look at some exciting work from the Central and Eastern European region.

Not a single day goes by without coming across written letters: they are with us in the morning on the subway posters, on our monitor screens, on the street, on the products we buy, but little is known about their different forms and their history. There is a dwindling number of typefaces that do not have a direct or indirect historical antecedent. The title of this article, for example, is set in Termina, a typeface inspired by a 19th-century typeface called Industria, although its designer Mattox Shuler insists that it is not a type revival project. Then what can we call a type revival?

Type revival—historically authentic, technologically contemporary

There is general agreement in the literature on type revival that revival means a shift between two platforms, and its history can be traced back to the 19th century, when William Morris used photographic enlargement to create the Golden typeface, inspired by the Renaissance lettering of typographer Nicholas Jenson. In contemporary type revival projects, the typographer adapts a typeface from an era before the advent of the digital technology, such as a Renaissance or even a twentieth-century typeface onto the digital surface—a good example of the latter is Tibor Szikora’s Margaret Neue, in which he modernized an antique variant of Margaret, one of the versions of which was made by typographer Zoltán Nagy in 1963 and which can also be found in Hungarian passports. Type revival is more than simply copying and translating old letters into pixels. Beyond preserving an important memory of the past, the exercise aims to add something new and unique to the history of the profession, and to us, the users.

“During a revival project, it can happen that the designer adds nothing to the original lettering other than adapting it to a new platform, just as it can happen that an overly abstract idea fails to retain the character of the lettering. I think the best type revival work is somewhere in between the two extremes,” says graphic designer Ákos Polgárdi, one of the founders of SUBMACHINE studio.

In this regard, graphic designer Nóra Békés quotes Matthew Carter, who says that “in a revival, as designers we stand on the shoulders of giants—but this means not only building on the work of the great typographers of the past, but also looking further from the shoulders of giants, thus we must learn from the products of the past to strive for new, more innovative results.”

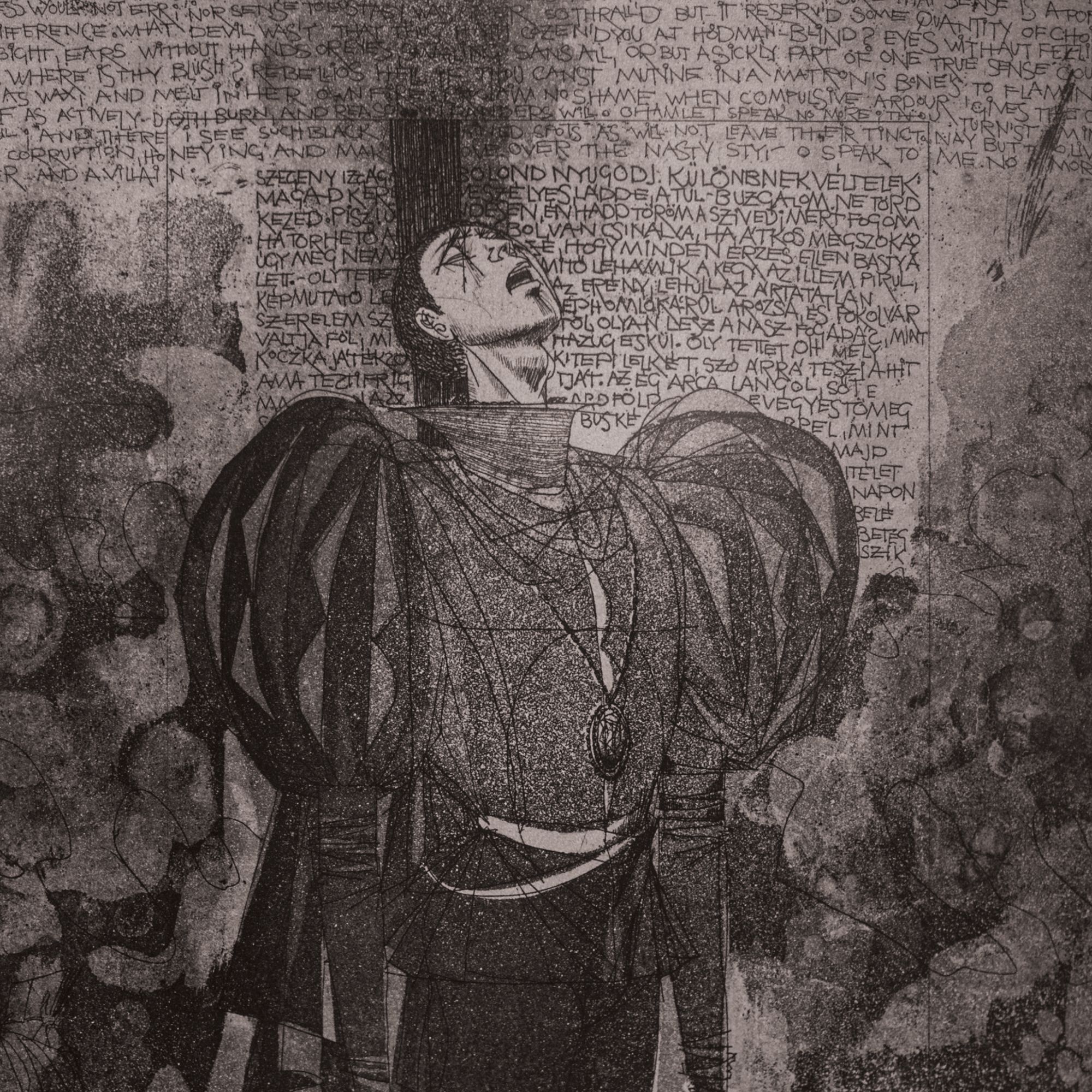

In a revival, sketches, a punch, a matrix, printed materials can all be used as sources, preserved in libraries, archives, museum collections. Typographic archaeology thus becomes an investigation for which a researcher’s attitude and interest in history are essential.

“When someone starts designing a revival or using a revival typeface, they are taking a typeface from a complex historical context and bringing it into the present. It’s important to understand what values and images are associated with the shapes, what their history is, who designed them and why we think it’s important for them to live on,” says Nóra Békés, who together with designer Céline Hurka spent years on various type revival projects at the Royal Academy of Art in Hague, the results of which are summarized in their book, Reviving Type.

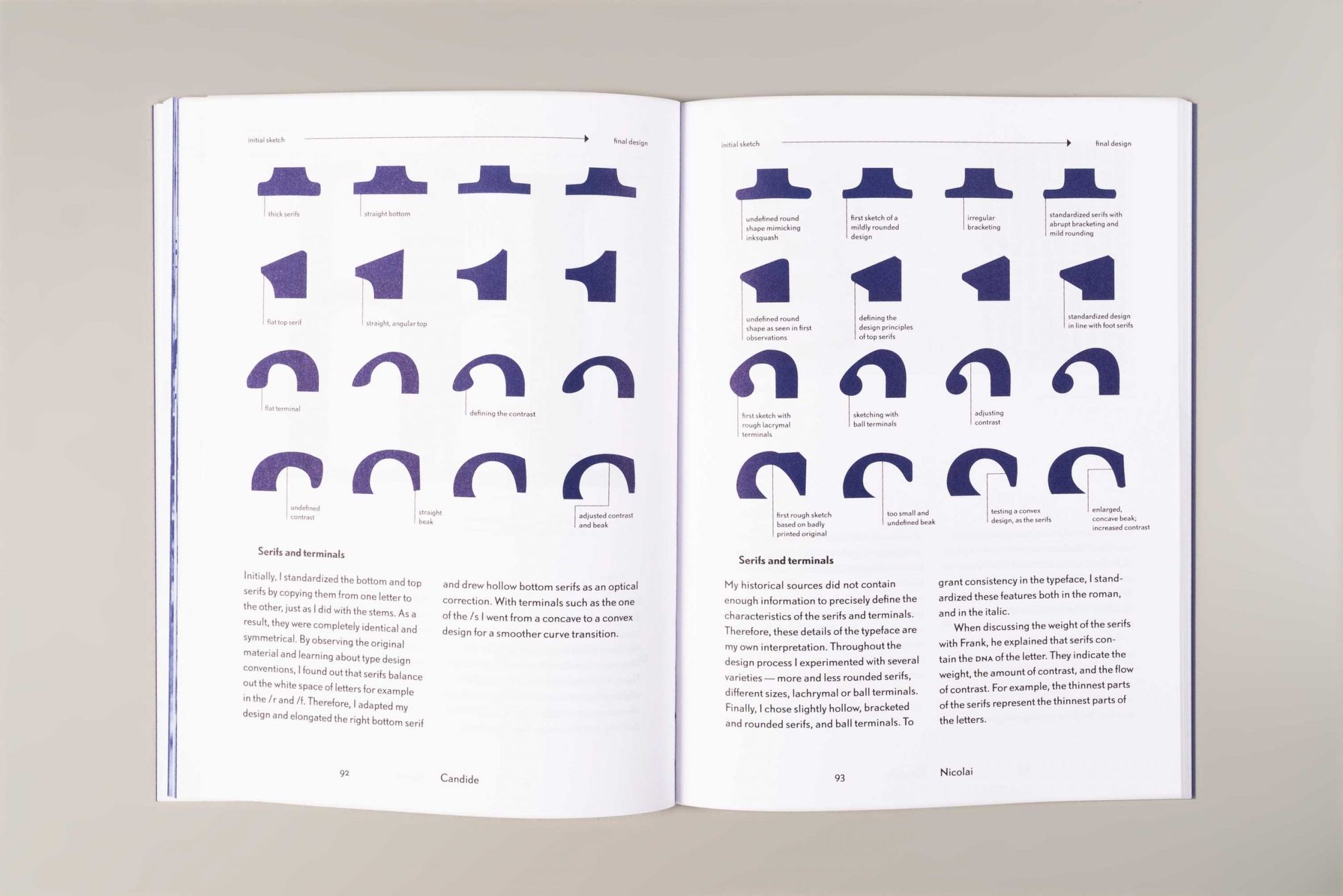

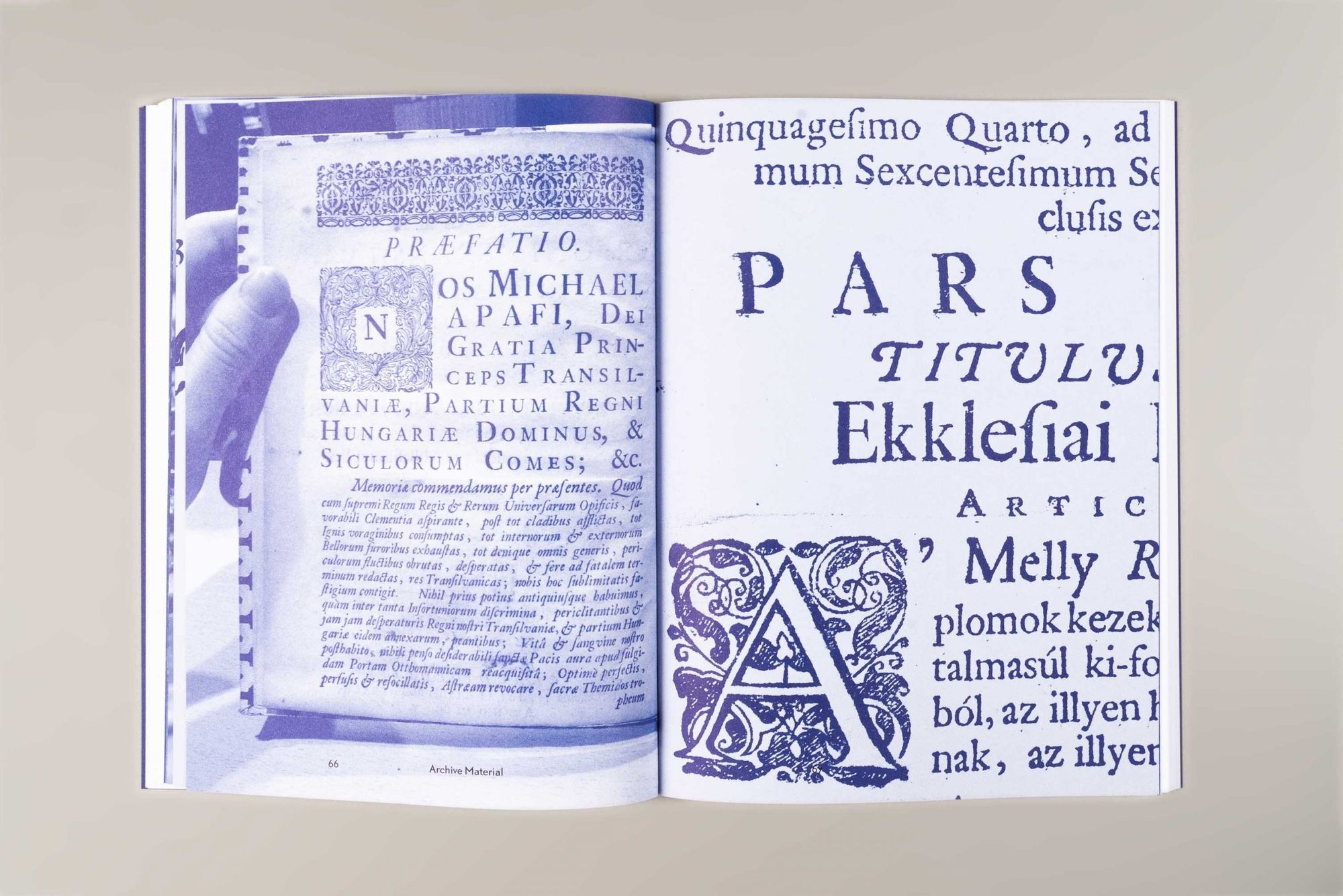

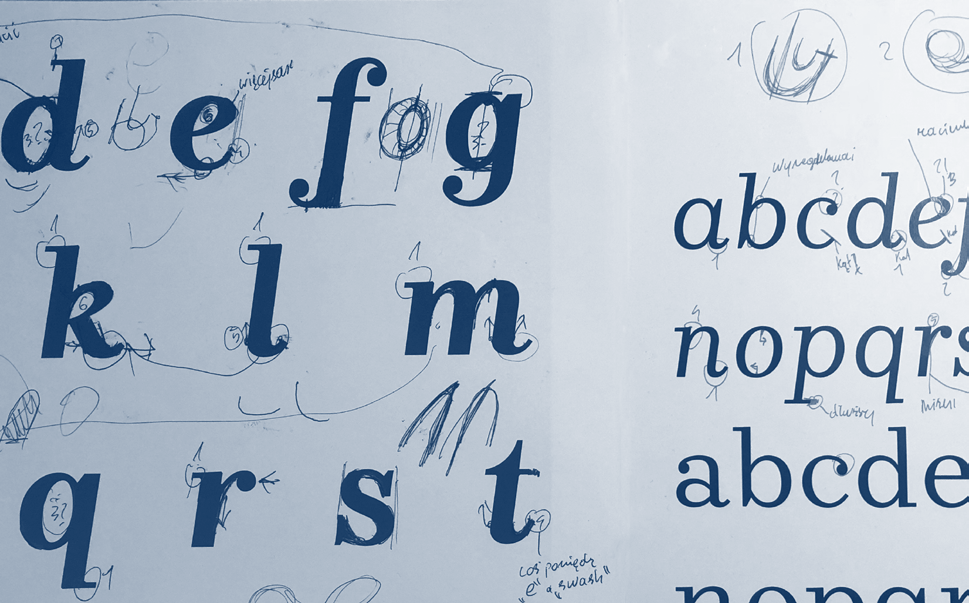

In the publication, Nóra Békés took the typeface of Miklós Kis Misztótfalusi, the only known Hungarian typesetter of the Baroque period, and Céline Hurka took the Renaissance typeface of Claude Garamon and Robert Granjon as their basis for the redesign. The strength of the book is that it presents the research and design process in a detailed and self-reflexive way, which should be useful for anyone starting a type revival project.

The DNA of the letter is what really matters

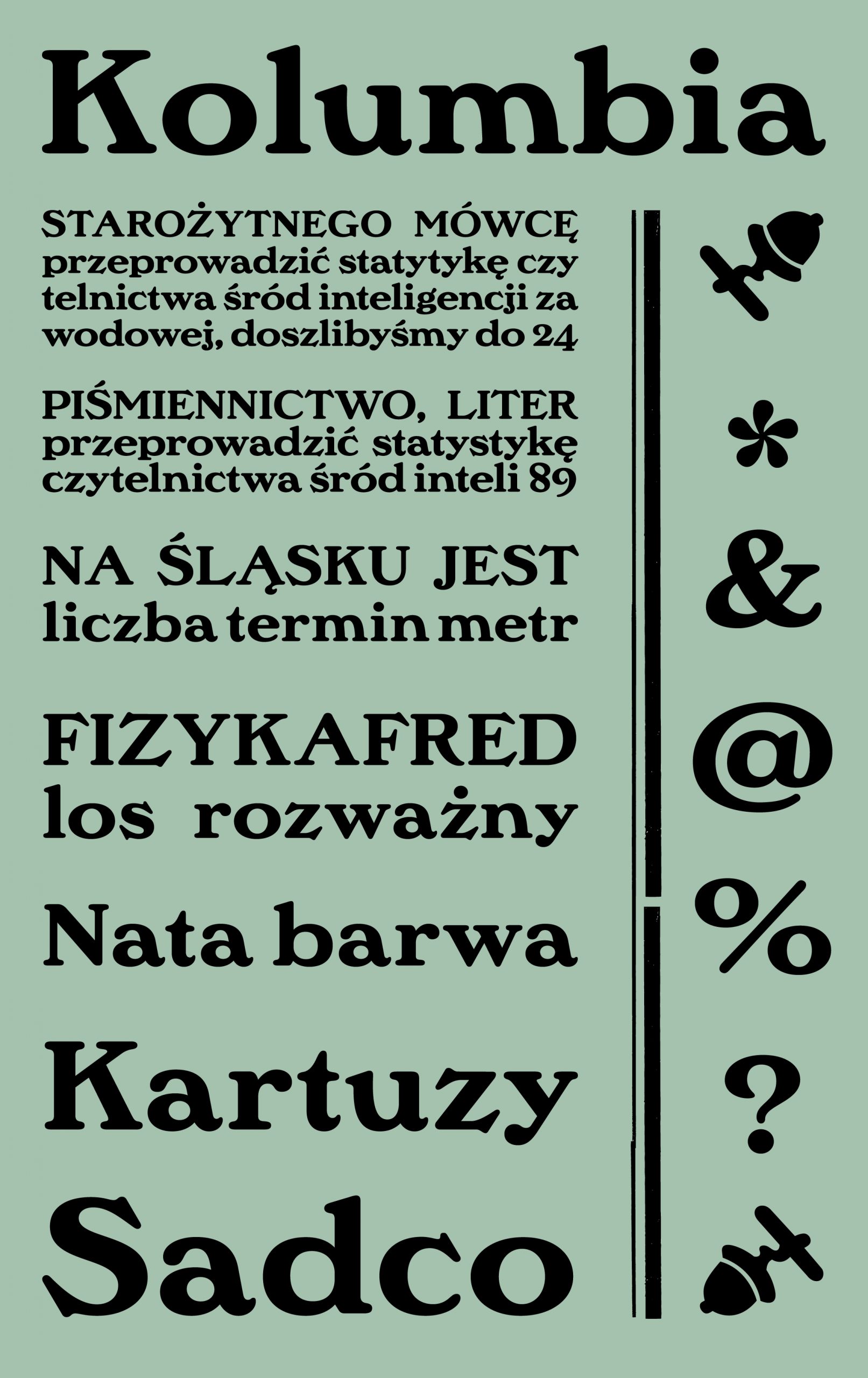

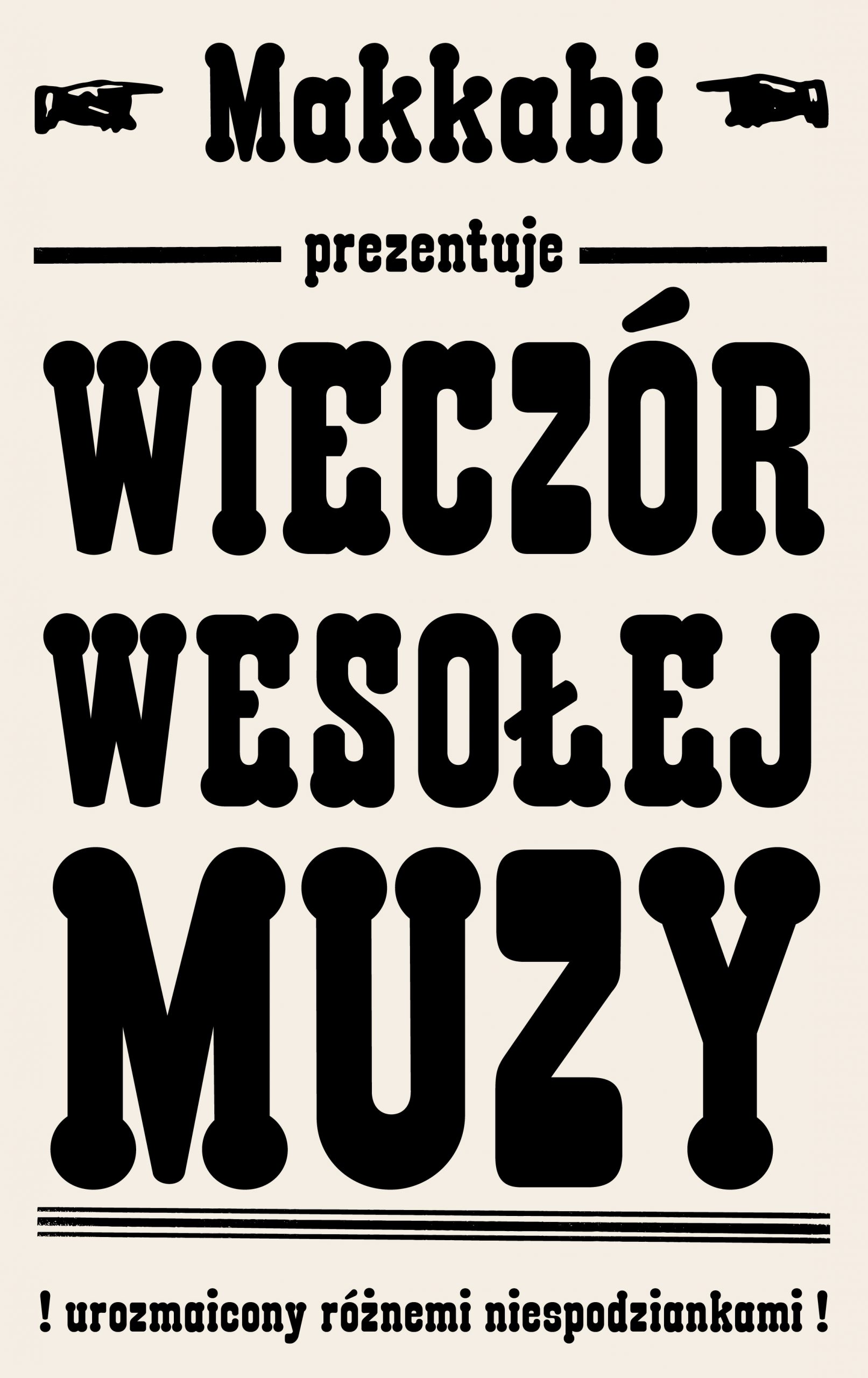

Historical revival projects are the most explicit forms of the genre, where the type designer captures the essence of the characters of a previous typeface and fixes them in a new, more functional form. However, the term type revival can be interpreted in a more inclusive way, as suggested by Ákos Polgárdi and Paul Shaw, author of Revival Type. According to a looser notion, handwriting, calligraphic work, or even letterings on posters, signboards, neon, graffiti can be considered as a source for a type revival. In this case, it is left to the typographer’s creativity to design the other letters of the alphabet and other characters. A good example is the typeface kass (cinketype) by Tibor Szikora, inspired by the handwriting of Hungarian graphic designer and illustrator János Kass, or the Polish Afiszuj się! project, in which professionals explored the history of Polish advertising material between the two wars. The joint work also included the digitization of three typefaces that were used on advertising prints of the time, although they are not Polish. In the liberated Poland after the First World War, Western typefaces were reborn with new names and minor changes.

A broader use of the term may also be justified because—unlike in France or Germany, for example—the Hungarian typographic history has far fewer Hungarian-designed predigital typefaces, but this does not mean that there is not enough material for exciting type revival projects in Hungary and the Central and Eastern European region. According to Ania Wielunska, on the Polish Typoteka site, for example, still many fonts are waiting to be digitized, and on the Hungarian part, even if the collection is not so rich in complete typefaces, there are still plenty of other inscriptions (for example, company logos or neons) and challenging materials worth preserving in the country, as Ákos Polgárdi points out. Some interpret the meaning of type revival in an even more inclusive way, including typefaces that reflect the visuality and creative spirit of a designer or artist’s work, rather than building on a specific written memory. Examples include the Mohol typeface family of Ádám Katyi (Hungarumlaut), which is most thoughtfully linked to the work of László Moholy-Nagy, or the Ladislav typeface of Tomáš Brousil (Suitcase Type Foundry), which pays homage to the legacy of Ladislav Sutnar, the designer known as the father of infographics.

Countries have an interest in preserving their cultural memories

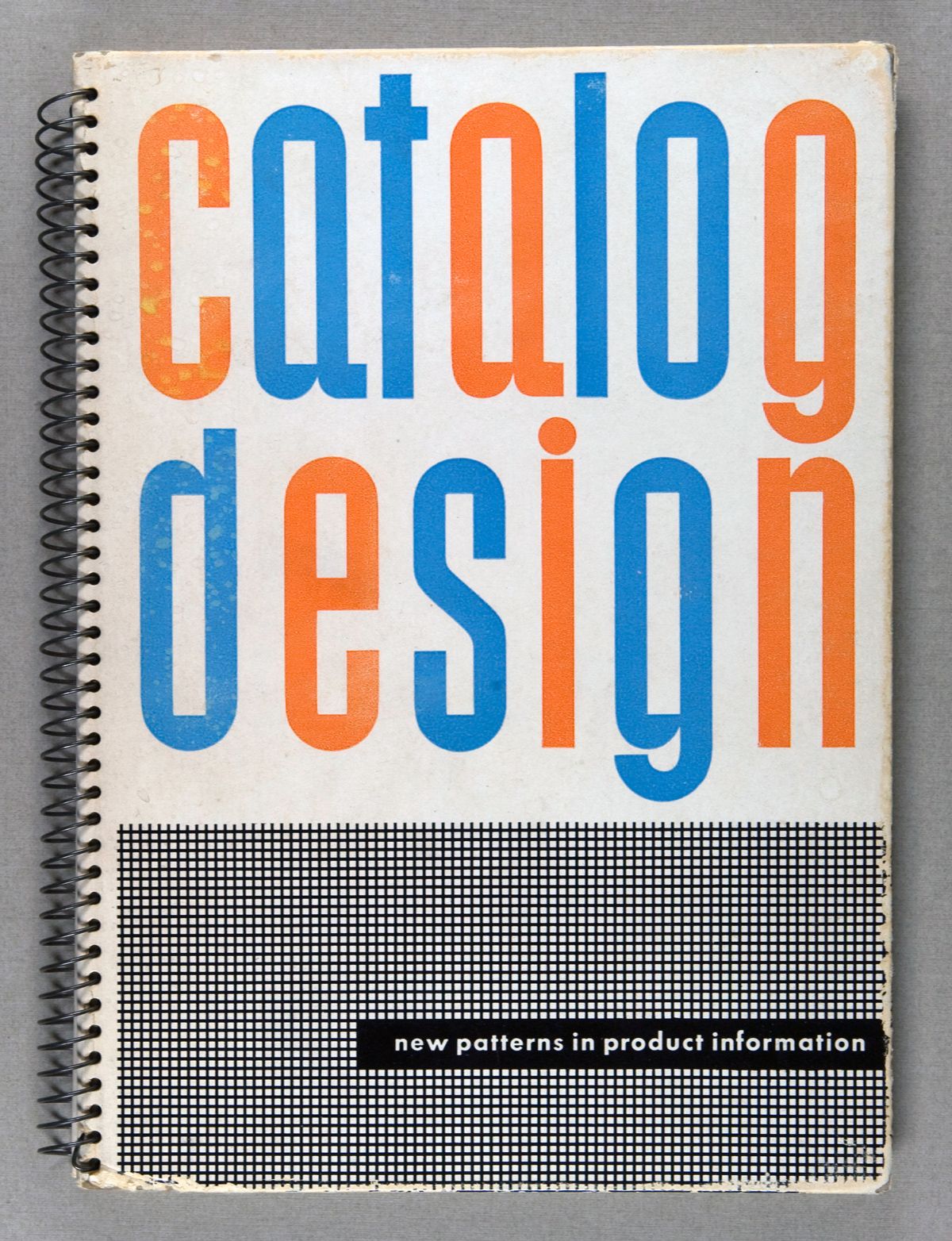

The Mohol typeface was created at the request of the László Moholy-Nagy Design Scholarship, which provides annual grants to young Hungarian designers and researchers, while the Ladislav typeface was used by the long-established Czech furniture brand TON in its 2014 catalogs. These examples show that a revival is much more than just another typeface when used in the right context—it can create continuity between the past and future values of a nation’s culture.

“While you’re working on a type revival project, you’re learning not only about culture and language, but also about type design, straight from your ancestors. Every revival contributes to the preservation of history—it’s a bit like conserving a piece of art and then displaying it in a museum, but here you’re creating a living, digital tool that people can use,” says Ania Wielunska, who, besides the above-mentioned Afiszuj się!, has been involved in several other type revival projects, including Brygada 1918.

Matrices of the original Brygada typeface were found in a Polish library in 2016. The typeface was probably made in 1928 to commemorate the tenth anniversary of Poland’s independence, but the designer’s identity is unclear, and it can only be presumed to be Adam Półtawski. The typeface was digitized for the centenary year with the support of the Polish Ministry of Culture and has been used by the government on official documents ever since. The Plecnik typeface family (Type Salon), inspired by the typographic work of architect Jože Plečnik, was also created in Slovenia with the support of the Ministry. The current popularity of the type revival in the Central and Eastern European region is thus fueled not only by technological advances and the emergence of software to aid design, but also by the need to preserve national heritage.

Many thanks to Nóra Békés, Ákos Polgárdi and Ania Wieluńska for their help in researching this topic.

Inclusive design development from Honda for the visually impaired

Hungarian success: a media designer won two Red Dot awards