Stereotype or reality? - alcoholism in our region.

Alcoholism is probably one of the most complex addictions: Firstly, alcohol is easily accessible; thus, many people can become addicted to it. Secondly, it is part of our culture to a large extent, so drinking alcohol is socially acceptable. Thirdly, alcoholism is stigmatized, so many people cannot seek help. Moreover, Central and Eastern Europe has been historically known for the population’s problems with alcohol abuse. But what is the truth behind this prejudice? And if the allegation is true, why did this become the case?

They are cold and corrupt, and above all, they drink heavily. This will be the verdict if one summarizes the characteristics of postsocialist countries’ people based only on stereotypes. But we must admit that the last element is partially true. The percentage of people struggling with alcohol dependence is the highest in Central and Eastern European societies. According to a 2022 survey, seven of the top ten states with the highest rate of people suffering from alcohol use disorder are former Eastern bloc countries; the other three are South Korea, the United States, and Slovenia. Hungary takes first place with a shocking 21.2%, while Russia is the second, just a bit behind, with 20.9%. Belarus comes third with 18.8%, a figure more than double the global average, followed by Latvia with 15.5%. There is a tie for fifth place: the figure is 13.9% in Slovenia, South Korea, and the United States. The last three on the list are Poland (12.8%), Estonia (12.2%), and Slovakia (12.2%).

Who is considered an alcoholic?

Many people might naively believe that alcohol dependence affects only the poor, less educated, marginalized groups of society. But well-educated people also often deal with alcoholism, despite that, at first glance, everything seems fine in their lives. Drinking alcohol is normalized in European culture; in a way, it is even expected. Most Europeans raise an eyebrow at someone who is not drinking and not at someone who is lulled to sleep every other day by booze. Alcohol dependence can be diagnosed by observing the patient’s specific behavioral patterns. If at least two criteria manifest, the person can be considered an alcoholic. Symptoms may include: the person has repeatedly been in a situation of self-harm because of excessive alcohol consumption, the person continues consuming alcohol despite having anxiety or depression from it, the person experiences withdrawal symptoms or has problems at school or work due to alcohol consumption. There are different stages of alcoholism: while some symptoms are only initial signs of addiction that could still be easily reversed, severe alcohol dependence can cause permanent physical and mental health problems with a risk of premature death.

Why is alcoholism prevalent in this region?

Surveys reveal that alcoholism is an enormous issue in Central and Eastern Europe, but what are the root causes behind the figures? The question is open to speculation. For instance, can our communist past play a role with its deep-rooted customs and idiosyncrasies still pervading the region? Turbulent history, the isolation of the bloc, and the communist system’s difficulties still significantly shape the region’s present. But it would be an oversimplification to claim that only historic reasons lie behind the fact that a significant proportion of the population has an alcohol dependence problem today.

Undeniably, the communist past contributed to the widespread prevalence of alcohol use disorder in the region. A 2018 survey revealed that those who lived under communist regimes consume significantly more alcohol than their Western counterparts. What is more, the more years someone has lived in a former Eastern bloc country, the higher their alcohol consumption is on average. Furthermore, this correlation is even stronger for women. Women from post-communist countries drink much more than women from Western countries, and the more they lived before 1989, the more they drank alcohol.

The causes behind the statistics are complex. Soviet propaganda encouraged alcohol consumption. Drunkard men were portrayed as liberated and attractive; even cookbooks often encouraged the readers to drink rather than eat. Those who did not drink regularly were considered outsiders. Mikhail Gorbachev, then General Secretary, tried to curb the spread of alcoholism with the 1985 anti-alcohol campaign by regulating alcohol consumption and putting up anti-alcohol posters. In the ’80s, alcohol dependence was already seen as a serious threat to society and responsible for hundreds of premature deaths. The Gordian knot of excessive alcohol consumption, already embedded in Russian culture, could not be cut that easily. The measures can be considered a failure, as alcohol consumption in Russia increased by 233% between 1988 and 1998.

Socio-cultural attitudes, permanent insecurity, poverty, and cold winters have all pushed people to drink heavily. And habits like alcohol consumption cannot disappear overnight; it takes generations to change people’s behavior. Moreover, an alcoholic parent’s child will be more likely to become an alcoholic than a non-alcoholic parent’s child. This is especially true in Central and Eastern Europe, where democratic transition did not lead to a change in drinking culture.

Melancholy is part of Central and Eastern Europeans’ identity, and the region's mental illness rate is also high. Mental illnesses are still stigmatized; it is almost taboo to talk about them in some areas. In Central and Eastern Europe, sweeping the problems under the carpet and not talking about our struggles is more common than openly facing personal challenges. The co-occurrence of alcoholism and other mental disorders, such as depression or anxiety, are well-documented. This reinforces the vicious circle: family and cultural patterns and the unwillingness to change can push nations into a negative spiral from which the way back is very difficult.

The consequences of alcohol use disorder affect the whole society, not just the alcoholists' families and immediate environment. Alcohol misuse is associated with an increased risk of premature death, accidents, and domestic violence, among many other negative things. Improving the shocking and depressing Central and Eastern European statistics will be lengthy and hard, requiring a joint effort. We should make reaching out for help and providing assistance the norm in the future regarding alcohol dependence. And above all, moderate alcohol consumption should be the new standard instead of heavy drinking. With these steps, we might achieve in the long term that not Central and Eastern Europe will provide the most data for addiction research.

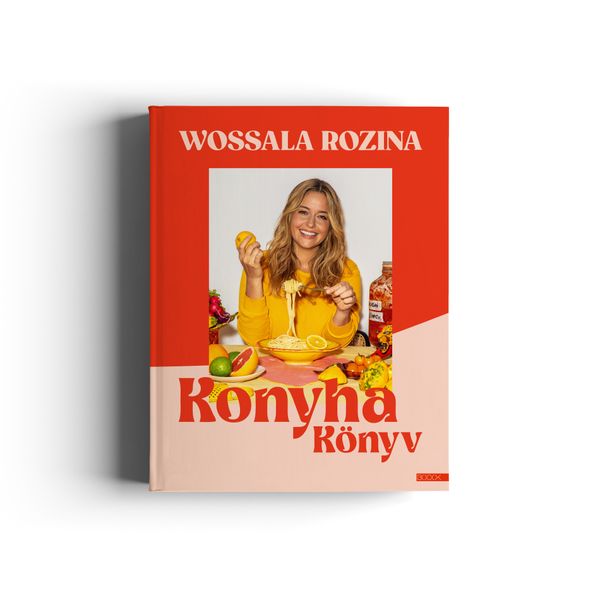

A journey round the table—introducing Konyhakönyv by Rozina Wossala

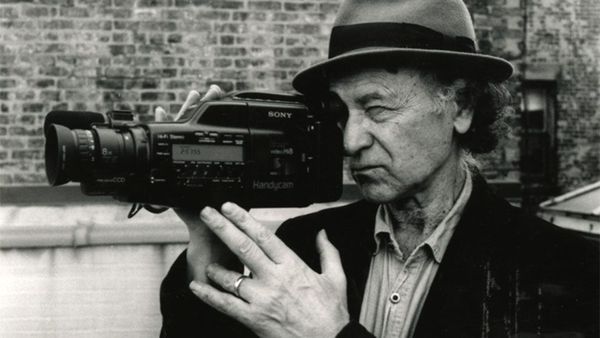

Memories and images—portraits of Eastern European artists at the Verzió Film Festival