There is a good chance that those who follow the gastro scene in Hungary have already met Antonio Fekete; they just might not know about it. Striking details, a clear, vivid look and the message that shines through, a quest for perfection—these are just a few of the things that characterize not only his photographs but his entire oeuvre, whether it is about cookbook rarities or his kitchen praxis.

Antonio grew up in Cluj Napoca and spent a large part of his childhood outdoors. Through countless hikes with family and friends, he quickly fell in love with nature and all things that have deep roots in it. He was fascinated by the raw authenticity of wild plants and mushrooms, the purity of honest flavors, how everything is right in front of us in its best form. You don’t have to look for it, you just have to notice it. Later, however, with a U-turn, he became interested in the technical field, in communications technology, but, strangely, at the urging of his family, he ended up choosing a career in the hospitality industry. His practical master was József Szántó, who saw his diligence and talent and threw him into the deep end by sending him to competitions already in his second year. At the time, cold-plate competitions were very popular in Hungary, and the elegant, aspic-covered splendid food creations and the feat of technique required to make them were hailed by the profession. Antonio had stood his ground and had been sucked into the competition world for 10 years, but he started to feel that he was not on the right track. After all, where are the naturalness, the roots, and the true professional foundations? In search of fresh air, he moved to Ireland and took up a position in a fine dining restaurant there, where he encountered a very different approach. For example, they harvested their own fresh ingredients from the restaurant garden and worked in a way that prioritizes sustainability.

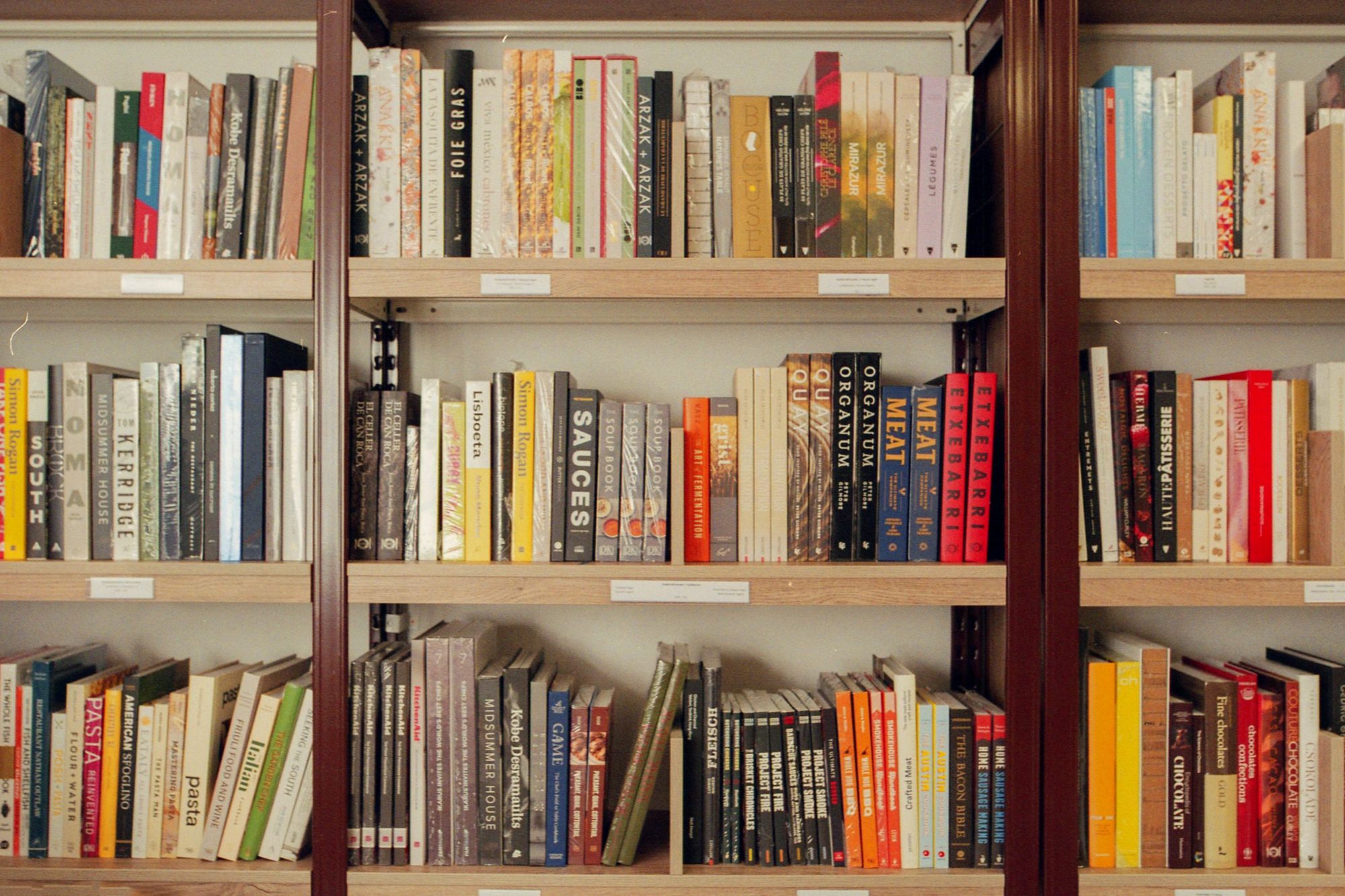

Once he returned home, he realized that what he had seen abroad was not working in Hungary for some reason. At that time, there was no Hungarian gastronomic revolution, no developed bistro culture or quality street food, just fast-food restaurants and a few old-fashioned places stuck in the last century, with one or two refreshing exceptions. The things got spiced up when Tamás B. Molnár’s critical articles on the culinary profession appeared. Although Antonio was also initially angered by the criticism, with time, he realized that there was some truth in it, which only increased his desire to learn. After his adventure in Ireland, he started collecting cookbooks and albums from all over the world, even in languages he didn’t speak—good old-fashioned dictionary learning never let him down. While working at LouLou Restaurant and later at the Golden Deer Restaurant, having seen his book collection, more and more friends approached him to get a copy for them, until he had so many quasi-orders that in 2011 he decided to start a business. And thus Cookbooks.hu was born.

“When I registered the company and told the administrator that my business would be bookselling, he asked me what type of books I was planning to sell. I said cookbooks, and the person started laughing. But I believed I was making the right choice.”

Books not only gave him inspiration about technologies and ingredients, but he also noticed a quality of food photography he had never seen before. There was no social media buzz back then, and current trends were dictating the standard of food photography. (The genre has been around since the 1950s when photographers replaced static images with romantic or even impressionistic compositions, and from the 1970s, with the advent of Japanese color printing, the limits disappeared. The starting point was no longer advertising but an aesthetic intention that makes you think— arouses desire as much as curiosity and excitement, or disinterest and disgust. The photographs initiate a dialogue with the viewer but do not exclude the consumability of their subject, starting a kind of visual “eating”—the Ed.)

Antonio saw the potential in this, a new form of creation and self-expression, and a new way to leave your mark. If something interests him, he will work on it until he polishes it to perfection, so he took up photography, went self-taught, took a deep breath and bought his first serious piece of equipment. At the restaurant where he worked, he was photographing the food after six months, and friends and colleagues were nagging him more and more to work with them. Previous relationships and experience as a chef helped him to look at the plate with different eyes than someone who had never worn a chef’s coat, so although his precision may have made him work slower, the results were significantly better and more natural.

In the meantime, Cookbooks.hu was also running in a handkerchief-sized, 12-square-meter shop while he was working at the restaurant kitchen and as a photographer. Although they belonged together, the different areas started to consume each other; therefore, he made a big decision again and gave up his career as a chef. Besides, he felt he had achieved what he could (only the Michelin star was missing from the collection) and was more moved by the broader discourse and other forms of creation.

“Nothing just comes and develops. You have to create it.”

As he became more and more known as a photographer in gastro circles, he had to create his own set of rules. He only takes on the amount of work that allows him to spend two days a week in the bookstore. He photographs no more than 15 dishes a day, preceded by a joint discussion: what will the color and composition be like? But, more importantly, what do we want to tell about the food and its ingredients? He believes that it’s not glossy gastro photos that make a real impact, but those with a noticeable message and details that almost come to life. It is a tribute to the food, the chef and the viewer/taster. Of course, freshness is another priority, which is why the dishes are finished together just before the picture is taken. There’s no other way to do it, but only in symbiosis, so you may be asked for your opinion and the recipe might change. It’s an absolute harmony, where, in the best case, there is no hierarchy—he is pleased by the fact that most of his collaborations go back years.

He believes that we can create value and make a difference if we are curious, precise and perfectionists, but we also reflect respectfully on each other. And if the chemistry is missing for some reason, you have to let go and move on—because, as with food, the ingredients can be a mismatch in real life.

Photos: Dániel Gaál

An exhibition on the celebration of information dumping

Gorgeous yet divisive—modern chapels in the region | TOP 5