The designer leads the way, the industry drops behind—the usual story. No one actually used Borz Kováts’ armchair, yet it still made it into the big book of Hungarian design, and it could have accomplished even more. This time, we focus on the Vargánya and the “red Ferrari of the Museum of Applied Arts”.

Armchair in the museum

The PVC armchair made in 1971 is a truly spectacular piece. Let’s disregard the data known already for a minute and approach the object from a fresh angle. Its shape goes against our classic ideas about chairs completely: this chair does not stand on four legs, one could also say that it doesn’t even have legs. Its crescent-shaped “tail” fits to the floor solidly. Backrest, legs and armrests merge into one here, and the whole armchair has a statuesque feel to it—this designer’s feat could have hardly been accomplished with the usual choice of materials (meaning: wood): it required plastic. Thanks to the upholstery, made with the collaboration of interior designer Judit Görgényi, the piece is almost calling us. In terms of colors and shape as well as use of materials, it is an absolutely bold piece—of course, in 2021 we hardly get surprised by anything, yet if we think of Hungary in the seventies, we must admit that Borz’s armchair was an extraordinary piece of furniture in its own day (another interesting fact: the Museum of Applied Arts added the object to its own collection in 1972, which means it purchased a contemporary object).

Space Age in the Balkan… and a little detour to Italy

Of course, a bit farther out West, neither plastic nor the cherry red color was surprising. The Space Age design wasn’t as far from us as one would think, only it had a different name around here. In the decades of the Cold War, the faith in the scientific-technological revolution reached design, too: in the late sixties, plastic prevailed in furniture and object design, especially in Italy, and the designers became much braver in general, they dared to experiment with new forms. The use of plastic opened new paths to designers in itself: the previous formal constraints became overridable, and in addition to glass used for lamps until then, synthetic plastics also appeared. In addition to the previously required elegance and practicability, playfulness also gained relevance: the shape of lamps were many times reminiscent of satellites and various celestial bodies, table lamps started to resemble mushrooms, and every nation created its own version. In Hungary, this was Borz’s “Vargánya” lamp (more on that later), it was called “Nesso” in Italy, and the likewise Italian Elio Martinelli also designed a mushroom lamp. Our latest discovery was when we came across a super-cool, orange-white-toned table lamp on the Instagram feed of made.in.yugoslavia—and even though it differs from the Borz lamp in terms of ratios, the mushroom phenomenon somehow still bugs us. This means that the Italian design got to the Balkan, too (and if it got there, then sooner or later it must have appeared in other fields of Eastern Europe in one way or another).

We went after it, and it turned out that the “Meblo” sign displayed on the plastic lamp denotes a furniture factory operating in the city of Nova Gorica, which also manufactured lamps from 1976, commissioned by Italian companies. The story is quite complex, as in 1963, six Italian brothers, the Guzzini brothers, launched their joint venture in Recanti, North Italy, under the name „Harvey Creazioni”—first they only manufactured decorative objects made of brass, and then from the second part of the seventies they shifted their focus to lamp production, and even experimented with plastic. They changed names several times over the decades (Harvey Creazioni di Guzzini, Guzzini, iGuzzini, Illuminazione Guzzini), and then they outsourced part of production to the city of Nova Gorica, Slovenia, to the Meblo factory, thus allowing the Balkan to get a bite of the best of Italian design. The mushroom lamp displayed on the picture was presumably designed by Luigi Massoni and Luciano Bottura in 1965 for the Guzzini brothers.

“The Hungarian Joe Colombo”

In terms of the international scenery, we see that many similar objects were born around the same time, regardless of geographical location. What determined the outcome of the design objects’ story was most often the economic situation and the preparedness of the given country’s industry (or rather its unpreparedness). There’s one more thing we cannot leave without mentioning: the spirit of the age and the public taste—in Italy, the road to success was open for the series-produced objects of Joe Colombo in the sixties, while at the same time in countries to the east of the Iron Curtain, the word “design” only started to spread. In Hungary and the Soviet member states, discourse revolved around applied arts(!), no designers were employed in factories and so the culture of the designer contributing to the marketability of the product could not develop. While in Hungary, the lamps of Borz Kováts could only make it into the selection of the stores of the Applied Arts Corporation, Colombo’s furniture pieces were manufactured by companies like Cappellini or Kartell. The fact that we refer to Borz Kováts as “the Hungarian Joe Colombo” is for a good reason: Cesare „Joe” Colombo studied architecture in Milan, while Borz studied at the Faculty of Interior Design of the Hungarian College of Applied Arts between 1959 and 1964, as a student of István Németh and György Szrogh (the architect of Hotel Budapest, amongst others)—the biggest difference between them is perhaps the fact that Colombo also studied sculpture and painting, while Borz completely distanced himself from visual arts.

Instead of series-production

In terms of talent, Borz did not drop behind his international peers: he applied a system approach and had an experimenting attitude, to him, instead of decorativeness, applied arts (or rather: design) equaled function. Resulting from his very nature and designer attitude, to him it was incomprehensible to join his applied artist peers in “serving” the Applied Arts Corporation—this was a dangerous thing to do, as we have already explained it regarding the “Felhő” lamp family. Borz didn’t want to expose himself to the Corporation (may it be about the quality of objects or the quite random product selection), thus, from 1966, he experimented in his own workshop, amidst small-scale industrial circumstances. In 1966, the “Rizike” and the admittedly Danish-inspired “Toboz” lamp families were born (Scandinavian design had always been very close to Borz due to their respect for artisan traditions and the organic, elaborate shapes—he even studied Finnish, and visited Finland once in 1968 in the framework of a study trip).

Even though Borz designed his objects to be suitable for series-production on a larger scale, the circumstances were not ripe—not a single factory showed openness to his ideas, so he was left with working in his workshop, of which Borz himself understood the limits and weaknesses. “…based on five years of manufacturing experience, I can say that the products carry the typical marks of specifically small-series production due to the limits of my workshop. This is because I am not in the possession of the relatively complex machines with which it is possible to make objects serving the very same function in a much simpler method, in a single phase of work,” reads his manuscript written in 1971.

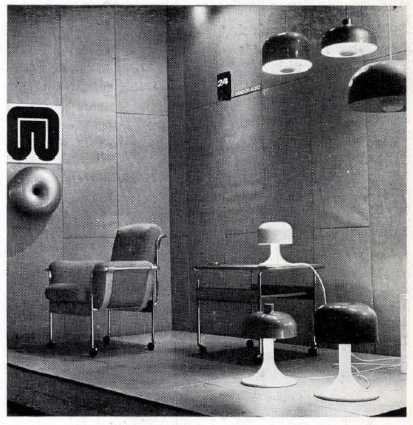

The Vargánya

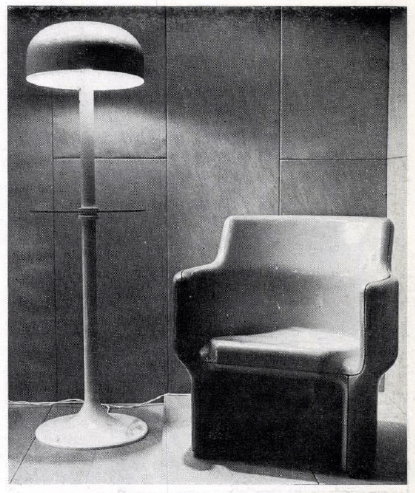

Between 1968 and 1969, the “Vargánya” (the name means porcini mushroom) lamp family was born, introducing table, pendant and standing versions. The kind of systematic design that is later manifested in the “Felhő” lamp family can also be observed here: the designer was not thinking in individual objects, separate from each other, and not only for aesthetic reasons, quite on the contrary. The identical structure enables cheap production (or, to be more correct: it would have enabled if the industry had been open to it). Borz formed the clean lamp shade and base out of aluminum, using the technique of metal stamping, and hides the light bulb away from the user—and for us, spectators, it might evoke the already mentioned “Nesso” lamp by Giancarlo Mattioli, released on the market in 1965 thanks to Artemide. And even though Borz had an aversion to the Applied Arts Corporation, he gave in eventually: the “Vargánya” and “Toboz” lamps both appeared in the selection of the Corporation’s stores, even though Borz remained in charge of manufacturing.

As opposed to the armchair preserved in the museum, the audience had a lot of opportunities to meet the “Vargánya”. The rooms of the Hotel Olimpia handed over in 1972 and made based on the plans of Zoltán Farkasdy not only had foreign tourists and Hungarian athletes among their permanent guests, but Borz’s lamps, too (Sándor Bedécs and Villő Detre were in charge of the hotel’s interior design—unfortunately the building has been demolished since). But there’s another hotel where one can still spot Vargánya lamps: the standing lamps pop up on the frames of the Hungarian movie “The Pagan Madonna”, in the hotel’s lobby.

Literature:

- VADAS József: A magyar iparművészet története, Corvina Kiadó, 2014

- VADAS József: A Művészi Ipartól az Ipari Művészetig, Corvina Kiadó, 1979

- VADAS József: Nem mindennapi tárgyaink, Szépirodalmi Könyvkiadó, 1985

- VADAS József: Mindennapi dizájn. Egy 68-as bútor. In: Kritika 2008. November, pp 20-22

- VADAS József: Borz Kováts Sándor. Egy legendás tervező a nagy generációból. In: Artmagazin, Issue No. 123, pp 70-76

Photos:

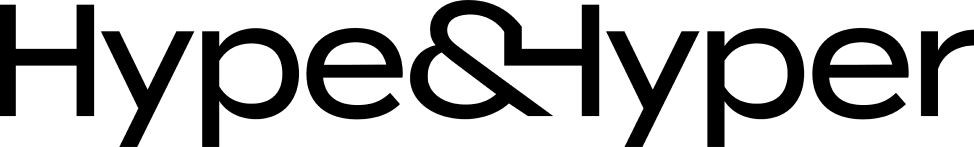

Photo 1: Plastic furniture. Source: Delta, 1972, Issue No. 4, pp 40-41

Photo 2: Sándor Borz Kováts. Armchair, 1971. Source: Museum of Applied Arts, Photo: Gellért Áment

Photo 5: Magyar Iparművészet, 1971, Issue No. 4, p 63, Photo: László Lelkes

Photo 6: Sándor Borz Kováts. Table, 1971. Source: Museum of Applied Arts, Photo: Dávid Kovács and Jonatán Máté Urbán

Photo 7: Sándor Borz Kováts. Armchair, 1971. Source: Museum of Applied Arts, Photo: Zsófia Kovács

Photo 8: Magyar Iparművészet, 1971, Issue No. 4, p 63, Photo: László Lelkes

Photo 9: Exhibition of applied arts corporations of Socialist countries. Source: Művészet, 1971, Issue No. 8

Photo 10: Sándor Borz Kováts. Table lamp—part of the so-called Vargánya lamp family, 1966-1968. Source: Museum of Applied Arts, Photo: Ágnes Kolozs

Photo 11: Sándor Borz Kováts. Pendant lamp with metal shade—part of the so-called Vargánya lamp family, 1968-1969. Source: Museum of Applied Arts, Photo: Dávid Kovács and Jonatán Máté Urbán

Photo 12: Sándor Borz Kováts. Metal casting form—the lamp family’s plastic metal stamping form, 1968-1969. Source: Museum of Applied Arts, Photo: Dávid Kovács and Jonatán Máté Urbán

Photo 13: Sándor Borz Kováts. Metal stamping form, 1968-1969. Source: Museum of Applied Arts, Photo: Dávid Kovács and Jonatán Máté Urbán

Photo 14: Sándor Borz Kováts. Pendant lamp—part of the so-called Vargánya lamp family, 1968-1969. Source: Museum of Applied Arts, Photo: Dávid Kovács and Jonatán Máté Urbán

Photo 15: Sándor Borz Kováts. Table lamp—part of the so-called Vargánya lamp family, 1968-1969. Photo: Museum of Applied Arts, Photo: Dávid Kovács and Jonatán Máté Urbán

Photo 16: Eötvös Road 40, Hotel Olimpia, 1972. Source: Fortepan / Sándor Bauer

Photos 17-18: Eötvös Road 40, one of the rooms of Hotel Olimpia, 1974. Source: Fortepan / Sándor Bauer

Photo 19: Eötvös Road 40, Hotel Olimpia, 1972. Source: Fortepan / Sándor Bauer

In our Object Fetish article series, we introduce the emblematic pieces of Hungarian object culture. We go after objects and their designers: we ask questions, we investigate and we learn. A four-hand piece by design theorists Kitti Mayer and Piroska Novák, published every two months.

In partnership with:

In the magical landscapes of Poland | Tatrzański National Park

Igloo-inspired prefab houses from the Faroe Islands | Kvivik Igloo