Jewelry designer Patrícia Harsány started a 100 day design challenge for the period of the lockdown: in her visual object diary titled Quarantine Jewellery, she documents a new piece created out of the objects found in her environment every day. The quarantine will be over soon, but the project keeps going – here comes the series currently in the making!

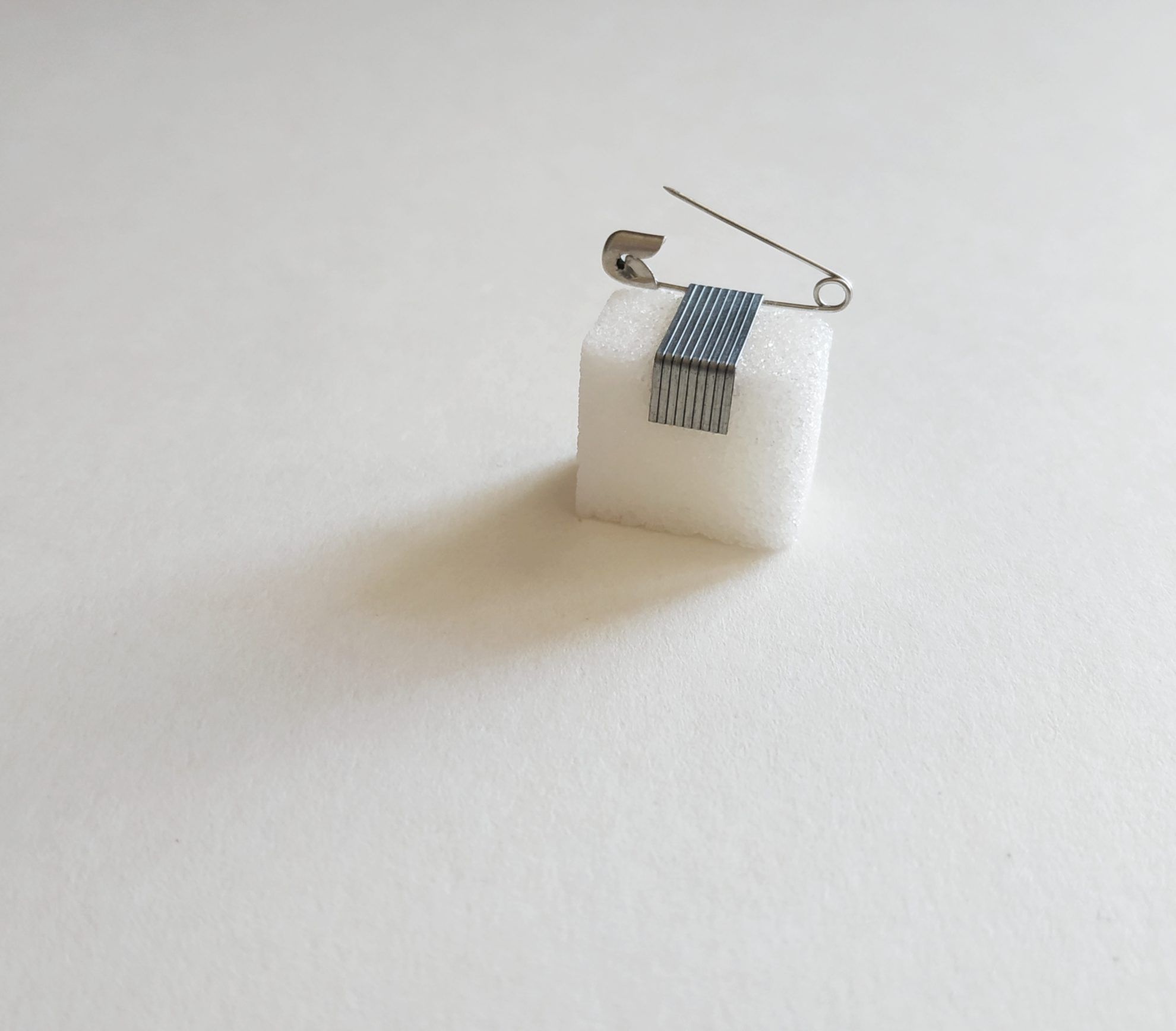

Threads, sponges, sugar cubes and a cookie cutter… perhaps jewelry won’t be among the first things that pop up in your mind when reading this list, however, Patrícia Harsány found a way to put the objects in her direct environment into new context in the form of contemporary jewelry. She started the Quarantine Jewellery visual diary in mid March, after the state of emergency was declared in Hungary due to the coronavirus epidemic.

“I moved back home to Karmacs, a little village in Zala county. This is the first time in some years that I spend a longer period of time at home. Everything that surrounds me is a little bit familiar and still new, as if I was reliving my environment as a child.”

The essence of the Quarantine Jewellery project is that the designer creates or documents a piece of jewelry every day during the lockdown that is made exclusively from the materials found in her direct environment. The junk drawers of the old family home, the pantry or the woods nearby all serve as sources of inspiration and a field for material collection. According to the designer, she doesn’t add anything to the pieces that she makes out of raw materials. Just like a puzzle; she is intrigued by the characters of the objects found and the possible ways of fitting the pieces together.

“When I find something, sometimes I see how I can connect it to the body right away, while at other times it’s primarily the combination of objects that appeal to me. Adjusting it to the body is more of a challenge in these cases.. Sometimes I don’t create anything at all, just discover a situation that results in a connection between the body and the object” – Patrícia told us. The latter method resembles the Dadaist artistic practice of appropriation, in the course of which the everyday object became a piece of art simply through the process of selection. However, the “found objects” put in a new perspective do not remain in themselves; the designer’s approach dictates in the moment of selection, and the creator looks at how the given object will be able to connect to the body. In this process, the shape of the object found and its characteristics allowing it to function as a piece of jewelry are just as important as chance.

I asked the designer about her favorite piece in the collection.

“One of my favorites is the Spiky Brooch. Probably all of us remember it from our childhoods; the annoying plant that keeps sticking to our clothes especially at times when it really shouldn’t… in this situation, however, all of it makes complete sense.”

Our childhood memories and seeing the abundance of objects piled up in the family home over years can make us all feel nostalgic. The absurdity of the situation brought on by the coronavirus is that the objects triggering nostalgia have suddenly become part of our everydays again. The narrative pieces of jewelry are the imprints of the everydays and habits of the designer; with her journal-like documentation, she invites us into her home and thus recalls a familiar feeling in those who found themselves in the seemingly endless video meetings of digital education and home office in the past period. According to the designer, Quarantine Jewellery was a good practice to maintain her creativity during the pandemic: “Every day seems the same, but with different objects, mood and creativity. There are days when I come up with multiple solutions and there are cases when I ruminate on a combination for weeks… Yet I feel that this daily routine keeps me focused professionally and gives me motivation.”

The personal and narrative nature of contemporary jewelry is demonstrated in a quite pronounced manner by several pieces of the collection, while the object diary is infused with spontaneity and humor. The work method applied is not completely new for Patrícia – a study trip abroad and the work of visual artist Mark Dion inspired her immensely, and later on she also incorporated collection as a work method into her design practice. Her LOST AND FOUND series which debuted at STAGE in 2019 was also born from the idea of recontextualizing everyday objects.

100 pieces of jewelry / 100 days – says the project description of Quarantine Jewellery. The 100 day period seemed realistic in mid March – and indeed, more than two months had to pass until the strict rules are slowly lifted, and we are still not where we were before the lockdown. Maybe we’ll never be there, and although each of us developed different strategies for survival and started different hobbies during the lockdown, one thing is common in all of us: we were locked in, with our objects.

A few weeks earlier Dutch designer Hella Jongerius talked about how we are urged by the time spent at home either consciously or subconsciously to pay more attention to our living space and our relationship with our objects in an interview (1). Whether the time spent in lockdown will bring a revolution in terms of how we think about the materiality and meaning of our objects as well as the social and ecological consequences of their production and disposal would be quite hard to tell at the moment. Nevertheless, the Quarantine Jewellery collection is an authentic manifestation of the fact that this period may introduce new factors into how we think about our object culture.

The quarantine story embedded into the jewelry is currently at Day 57. The works that have been created so far are available on Instagram and the website of the project.

(1) Jongariaus, H. (2020) Interview with Tim Marlow within the framework of #DesignDispatches. April 25, 2020 Available: https://www.instagram.com/p/B_Z3VSWnQ7C/ (Date of access: 20.05.2020)

"Designing with instead of designing for"

IKEA | Your very own bee apartment