In the exhibition Borderline Case—which opened its doors to the public on 22 January—Hungarian, Polish, Czech, Slovak and Romanian artists born after 1989 explore the relationship with their own regional identities. What can the region do, after being conditioned to forget its own past in order to move on after the fall of the Soviet Union?—asked Flora Gadó at the exhibition opening. The artists of the works on display at the MODEM exhibition space in Debrecen are starting the process of coming to terms with, and moving past, the legacy of socialism. Part of the strategy is to deal with pressing social issues, and to use nostalgia, critical perspective and irony. We spoke to curator Don Tamás about the exhibition.

During the guided tour you mentioned that you first started dealing with the relationship between Central European identity and your own generation two and a half years ago. What sparked your interest in this topic?

I’ve already had several curatorial projects dealing with the issues of identity, including the exhibition For family reasons, organized in 2019 at MODEM, as well as my project series titled Vanishing Points, which explores anti-Semitism and Jewish identity in different periods of the twentieth century (Editor’s Note: the current event– A Slower Dawn!—Vanishing Points 4.0 is on show at Trafó Gallery until 30 January). On the other hand, the Határeset exhibition is also connected to my Master’s degree thesis, which I completed at the Hungarian University of Fine Arts. I researched the possibilities of integrating emerging artists into the institutional system of the arts. In regard to this, we organized a group exhibition at MODEM, together with Vanda Sárai and Ferenc Margl, titled Times of our lives?—starting perspectives, where we presented the works of artists in their first five years after graduation. In some ways, this is a continuation of the Borderline Case exhibition, where a broader immersion in the topic can be seen, with Hungarian artists alongside emerging artists from the region. Despite the fact that the artists featured don’t have a first-hand experience of the socialist era, I was interested to see whether its legacy is relevant to them in today’s globalized world.

What kind of responses have you seen? Is it possible for the works to express how artists in the region experience their Central European origins?

I would have liked for the works to raise different perspectives and further questions rather than similar answers. However, if we would really like to identify a common ground, then it could be irony—as this is an element that appears in a relatively large number of works, however, it’s used differently by everyone. Additionally, the majority of artists have focused on aspects of different periods in the past. Vasile Câtârâu, for example, dealt with urbanization and industrialization, David Prílučík focused on the breeding of Czechoslovakian border guard dogs in the 1950s, while Jiři Žák dealt with the relationship between Syria and Czechoslovakia in the 1960s and 1970s. Furthermore, besides specific historical events, Olga Dziubak addressed more general issues, who pointed out how power is exercised over the bodies of individuals, or for example, Dániel Bozzai and Dániel Máté examined the relationship between the areas where food commodities are grown and artificially defined national borders.

How has your research shaped your opinion on the search for a Central European identity?

I had to come to terms with the fact that it’s a far more complex issue than I originally thought it would be when I first started working on it. You can’t blame the region’s disconnection on decades of socialism in the region—it has to do with a much more complex social and historical phenomenon that goes back centuries in time. The novel Borderline Case (and also the exhibition’s name) by Péter Hunčík, a Hungarian psychiatrist living in Slovakia, which tells the story of the region’s twentieth-century history through the inhabitants of a small Slovak town with a mixed population living on the border, also had a major influence on my thoughts about the region.

Most of the works showcased at the exhibition were created especially for the occasion, and the event was also supported by extensive historical research. Did you have active discussions with the artists in regard to historical foundations?

The process of working together was smooth, although I had to realize that it’s not only young Hungarian artists who are difficult to find in the online space, but also artists from the region. The list of artists was compiled over several months with the help of many colleagues from home and abroad, but before I reached out to the artists, I asked Gábor Egry, Director of the Institute of Political History, to join me in the research process. We discussed the various definitions we would use pertaining to Central and Eastern Europe (In the end, artists from the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Slovakia and Romania participated in the exhibition—Ed.). Together, we defined the period from 1848 to present as the time frame for the study, as well as the themes of language, borders and regional self-definition as simplifying aspects that can help focus the research. Once this was done, I sent English translations of the research findings to the artists abroad, and we consulted a few times. Originally, I had plans to visit the countries taking part in the exhibition, and go and visit studios, etc., but unfortunately, Covid prevented these trips from happening. In this respect, it was easier with Hungarian artists because I had worked with them before, or in their case, I could visit their studios.

In the exhibition space there are several references to memorials. What message do the works on this theme convey?

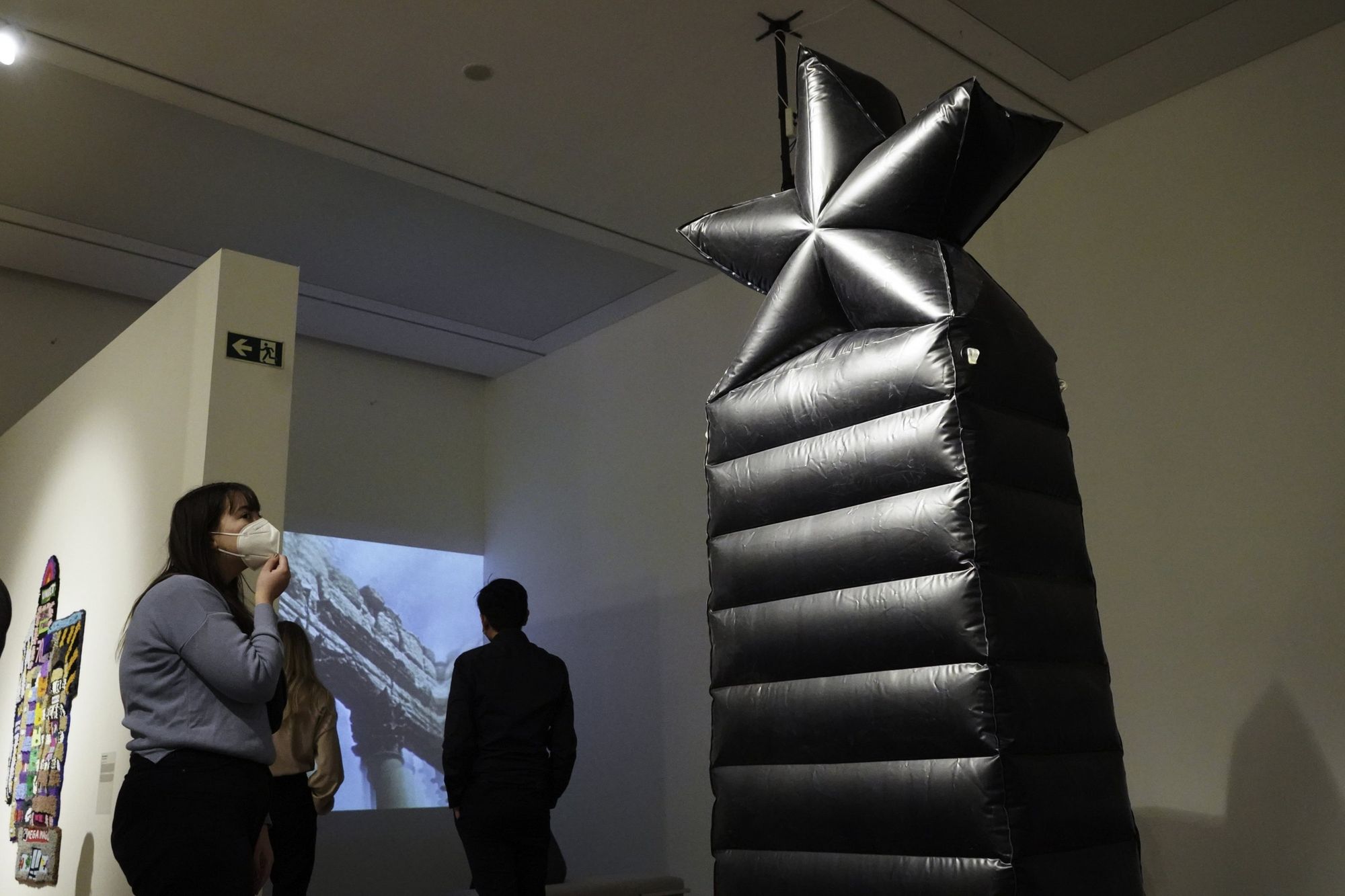

I have to state that I’m not an expert on the subject, however, it was clear from the research that the issue of memorials is of particular importance in the region, and indeed there are some works in the exhibition that deal with it in a direct way. For example, the work of Uladzmir Pazniak—a model of a Soviet heroic monument made of inflatable balloons—is in line with the theme of József Mélyi’s doctoral thesis on the export of monuments from the Soviet Union and how they defined the urban landscape in the countries of the region, even to this day. In contrast to Pazniak, Irmina Rusicka takes a more contemporary approach to monuments, questioning the very existence and legitimacy of the genre. The artwork is a strange, wrecked object, a bus stop that may stand somewhere between East and West, but we don’t know where we are or where we are going from here.

Besides the monuments, the visual and material culture of the socialist era is reflected in the space through other examples, such as with references to iron and concrete playgrounds, tapestries, and the world of 1970s cartoons…although the artists were born in a different period, it seems as if these elements also contribute to their articulation of a Central European identity.

Yes, the countries and cities of the region are still defined by the visual culture of socialism and its imprints. The paintings of Drozd Martina Smutná, for example, depict deconstructed social-realist statues, soldiers, partisans and workers. These figures are presented as frail and fallible, and with them the ideology in which they were born—a testimony to the fact that utopian ideas about socialism now seem naive. Or there’s Megan Dominescu’s equally ironic tapestry of an emblematic Bucharest building. One visitor of the exhibition even remarked that the work captures Bucharest perfectly. This work of art perfectly illustrates what can happen when an Eastern European city strains itself in its quest to be Western.

In the context of Judit Lilla Molnár’s work, the exhibition also raises the problem of the difficulty of establishing a global presence as a contemporary artist in the region, although this tendency is starting to improve. What are the reasons for this improvement and how can it be strengthened?

I don’t have enough insight into the contemporary art institutions in the neighboring countries to be able to comment on their situation, but for sure globalization is a helping factor. Today, if you manage yourself well, get into a gallery, and gain visibility in the online space, it’s easier to make your mark on the international scene. The fact that the region’s artists are lagging behind in the latter is not only their fault—it’s the responsibility of the entire contemporary institutional system of the arts, especially educational institutions. In the 21st century, an art university should also be about giving guidance to students on how to succeed in their post-graduate years. Furthermore, there’s also a need for a carefully considered renewal of the different segments of the institutional system—but this is not possible in most places due to a lack of resources and other problems.

Borderline Case—Contemporary Reflections on Central-Eastern European Identity

MODEM Modern and Contemporary Arts Centre, Debrecen

January 22, 2022.—April 10, 2022.

Exhibiting artists: Silvia AMANCEI & Bogdan ARMANU, Dániel BOZZAI & Dániel MÁTÉ, Vasile CÂTÂRÂU, Jakub CHOMA, Megan DOMINESCU, Olga DZIUBAK, Mátyás ERMÉNYI, Judit Lilla MOLNÁR, Uladizmir PAZNIAK, Renata PINTEROVA, David PRÍLUČÍK, Irmina RUSICKA, Drozd Martina SMUTNÁ, Jiři ŽÁK

Kurátor: Don Tamás

Photos: Ferenc Kocsis

Cover photo: Dávid Biró

Modern self-sufficiency on the island of tranquility | Mandrova house

Polar bears have moved into abandoned Russian houses