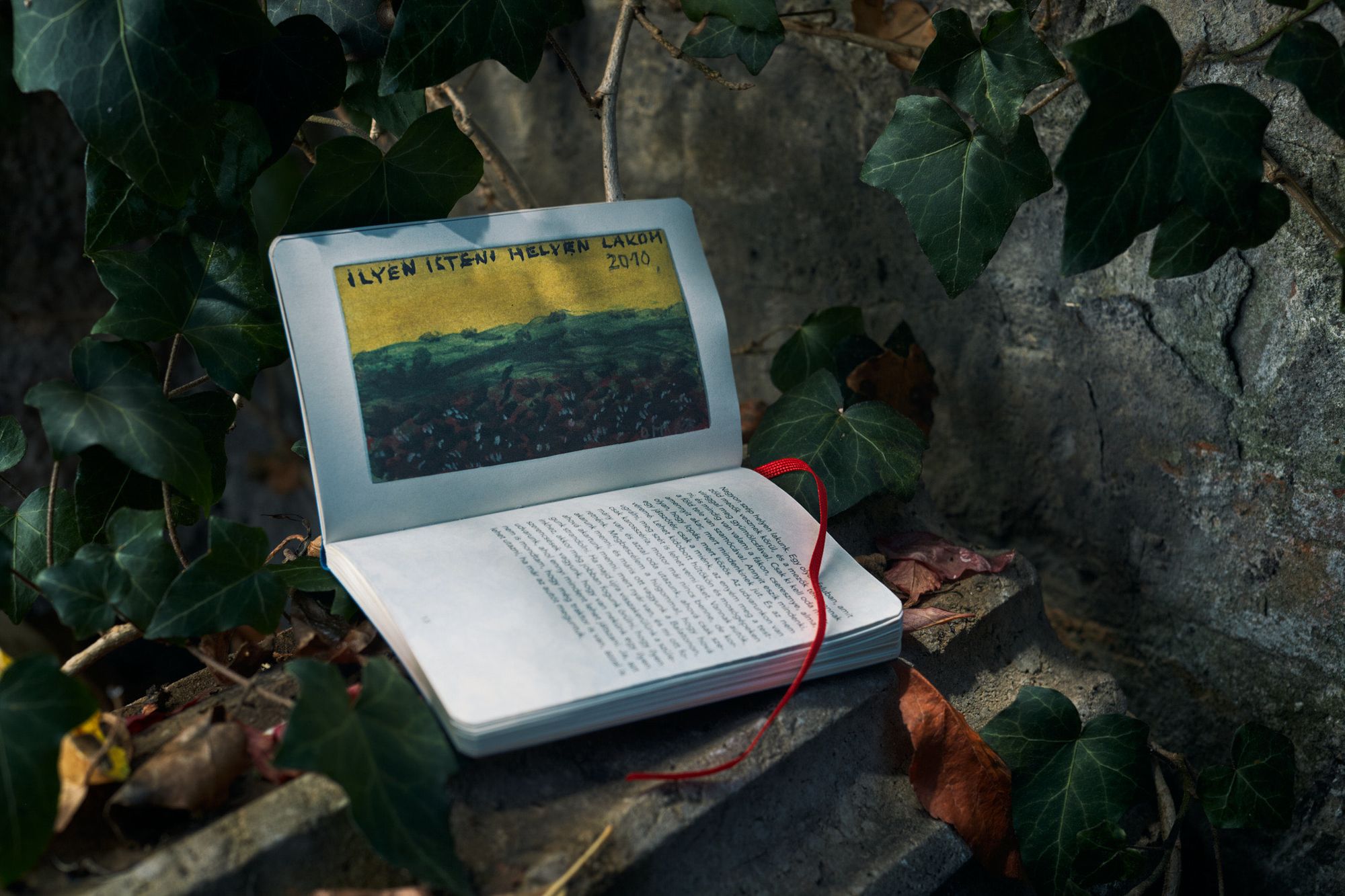

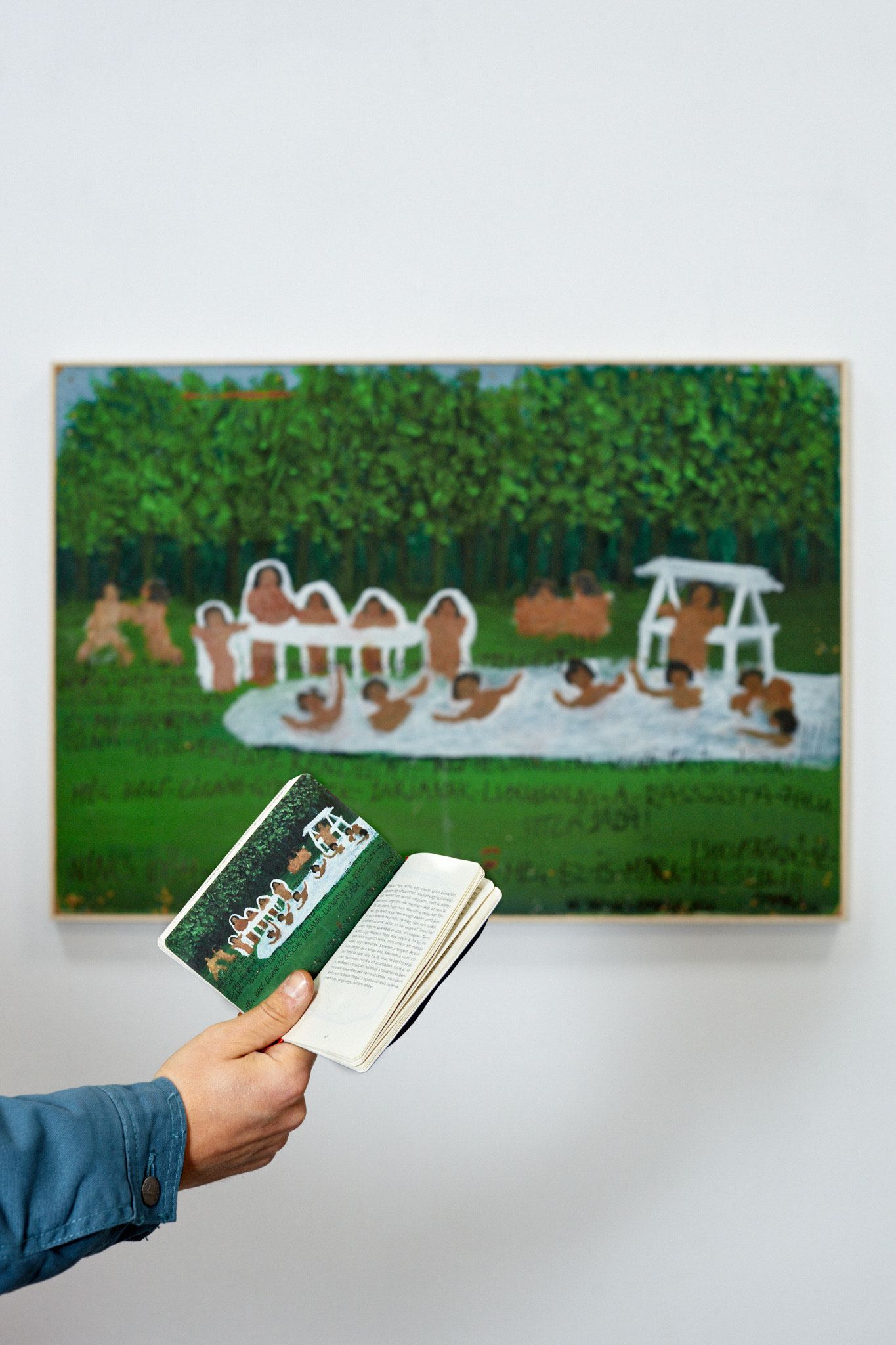

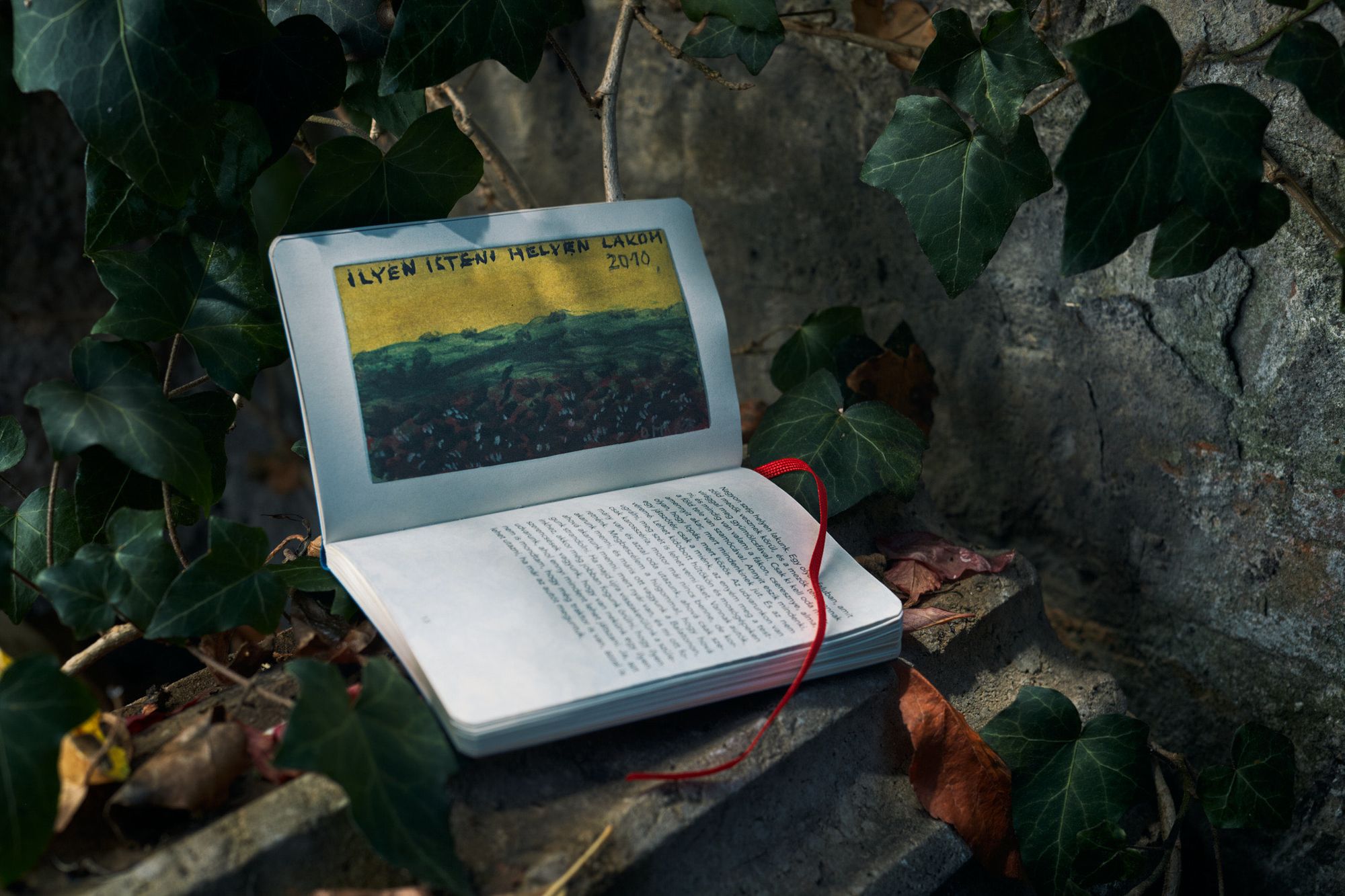

An exceptional encounter between two artistic disciplines and creators is embodied in POKET’s new, extraordinary all-arts volume. In the miniature book Amit gondolsz – az van lefestve (What You Think – It’s Painted—free translation), János Háy has written text sequences for sixty paintings by Omara—Oláh Mara (1945-2020). Over the weekend, we attended a book launch at the Ludwig Museum, where the author, accompanied by accordion (involving a third art form), read from his heartwarming and heartwrenching reflections.

POKET, a project of Miklós Vecsei H. and Krisztián Grecsó, aims to promote reading and to build community. They do this by placing pocketbook vending machines in busy spots across the country, providing access to small-sized but affordable reading material. The idea for this book came from POKET’s Emese Asztalos, Anna Sidó, Panna Horváth and Everybody Needs Art’s gallerist, Péter Bencze. “I don’t like to treat arts separated because mixing them can give a much more complex experience. That’s why we didn’t want to publish an analyzed catalog of Omara’s art. That wouldn’t be our thing. In the book, a question-and-answer relationship develops between painter and writer, in which the reader joins in as a third party. In this way, the three readings meet, which is an opening towards Poket’s overall artistic ambitions,” Panna told us.

Mara Oláh, who had a troubled fate and worked as a cleaner for many years, was born in Monor in 1945 as the daughter of a musician and a Boyash Gypsy. She went through some severe illnesses during her life, including a tumor that required an operation on her eye. “I started painting during one of these critical periods in my life, after the sudden death of my mother in 1988. I felt killer headaches. On one of those migraine days, I asked my daughter for a pencil and paper because I felt I had to draw. That’s when my painting started because, by the time I finished the painting of Sophia Loren, my headaches were gone, as if they had never happened. My relatives thought I was stupid for painting. I painted over a hundred pictures. I gave them away, keeping only one painting of my eye operation. In November 1991, I took this painting to the National Gallery to ask for their opinion on whether it was worth continuing to paint it. The experts encouraged me to continue. After that, I started to receive invitations to various exhibitions,” says Omara on her website. Mara, who died last year, went on to become one of the most important figures in contemporary painting in Hungary, winning a place at the Venice Biennale and eight of her Blue series (which, despite misconceptions, has nothing to do with Picasso) are in the permanent collection of the Ludwig Museum. Hence came the inspiration for the venue of the book launch.

The sixty artworks that make up the texts’ basis were selected by Emese, Anna and Panna from Peter’s vast Omara collection. In the beginning, the question arose: should the undertaking be a gypsy book, a book by a gypsy painter? Then they agreed that it should be a reflection, not a direct community engagement. Therefore, they approached János Háy to reflect on the paintings without any formal limitations. They chose the writer for his recurring character texts (such as the recently published Mamikám), his sensitivity to the subject, and his ability to tune into a child’s perspective. It was also important that the texts should not illustrate the pictures, as the captions are an authentic part of the works. “It is part of Mara’s free conception of life that she painted exclusively figurative images without texts at the beginning of her painting career. Then she had an exhibition in Szeged, where she painted the funeral of one of her brothers. The Roma funerals are accompanied by a party. While crying and smiling, Mara’s glass eye rolled out and she got down on all fours to look for it. But the exhibition’s director named the painting ‘Mara at Rest’. When she saw this, she ran headlong into the first stationery and returned to the exhibition space with a felt-tip pen to write down the story. From then on, she started captioning her paintings so that what she wanted to say to the world would not be misunderstood. That’s what makes the whole oeuvre and the personality so authentic that she stuck to it until her death,” said Péter Bencze at the event. The free literary associations of Háy were born with this line of thought in mind. The artwork-pairs that can be interpreted separately but together form a new entity, tell stories of parent-child relationships, love, poverty, everyday joys and sorrows.

Háy had never met the artist in person, so a fresh yet deep emotional identification occurred during the text creation process. “When you start something, you already feel if you have a tendency towards it, but you don’t know how you’re going to do it. When I managed to put the images in order, suddenly the story, the emotional games of this life, appeared—to use a word foreign to Omara—metatexturally before me. My girlfriend told me that she saw that my heart had grown while writing these texts. Some profound change happened to me. By the end, I was like, why are there only sixty of them? It could have been eighty or a hundred. Any number,” said Háy, who finally handed in the finished texts to the Poket team well before the deadline. “Finding out what the creator wanted is what’s really interesting. I have to go down that road myself. By having it now as a task, there was no escape; you had to think it through, go into it, be there. It’s like when you translate something and you manage to find the heart of the original creator. This story is about nothing else but finding the heart of the images. Our greatest difficulty in life is how to keep a free and clear view of the world. In what Omara does, the chance to have a clear view is offered. This is a huge thing. In general, everything struggles to make us tunnel-visioned and canonize us, to pigeonhole us in our thinking, in our public life, in our customer habits. Everything that works against this is all about the truths of human life. It’s about the fact that emotional identification is the only way for human existence. Everything else is unnecessary and false,” the author said at the book launch.

The book has been well received by both Mara’s relatives and Poket readers, who, according to Panna, have written more messages than usual. And Péter Bencze evoked the spirit of the artist in the foreword, wondering what she would have said to all this: “Dikh a Mara!!! I’m laughing my head off; people are crazy about this miniature book. My scribbles, along with the writings of my beautiful soul, János. You see, my little boy, that’s why I always say I would be a whining bitch all the time if God hadn’t given me painting after my illness. I would be a fuddy-duddy, bitter old woman. But this way, you won’t find a bigger badass on Earth.”

At the intersection of culture and fashion—Interview with fashion historian Darnell-Jamal Lisby