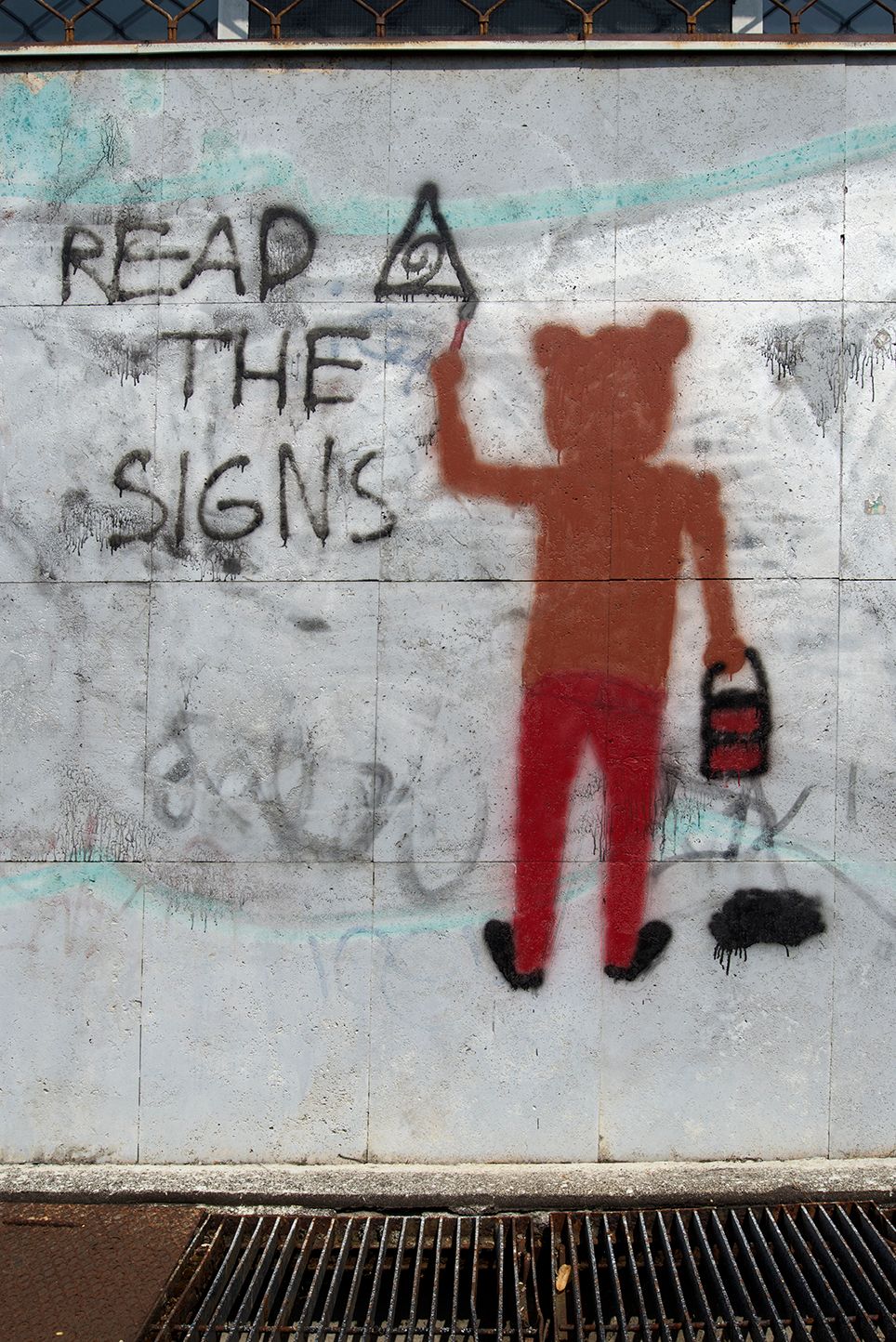

Short messages, unusual typography, amorphous figures, and boundless imagination—that’s graffiti, or “urban folk art” as photographer László Lugo Lugosi called it. GRAFFITI. Read the Signs is a posthumous album of one of the last series of photographs by this important figure of Hungarian photography.

“Essentially, I want to photograph the changes in time. In the case of graffiti, it’s about how interesting such a photograph will be in fifty years,” Lugo said of his graffiti series. In 2019, when I organized a building photography workshop led by him, standing on the steps of the Ludwig Museum, we talked about Budapest. At the time, as he told me, he was working on his images capturing the changes in the Ferencváros district of Budapest. As we looked to the left, on the other side of the Danube, on the Kopaszi Dam, the MOL Tower and its surrounding houses were already under construction. He said he liked it. That he liked all changes. I was shocked at first, and later I thought of his words many times. Then I realized that he had a different view of the city because change can only be photographed where it occurs.

In his 1994 album Eltűnő Budapest (Vanishing Budapest—the Transl.), published in collaboration with Aliona Frankl, he captured the last representatives of dying crafts, workshops, and store interiors. In Budapest 1900-2000, he re-photographed György Klösz’s (1844-1913) images of turn-of-the-century Budapest, highlighting the changes in the capital’s representative sites over the course of a century. In contrast, in the GRAFFITI series, he roamed the city’s non-sites—abandoned buildings, rust-belt areas, or simply spaces overlooked by all—to document the unrecognized and illegal art of anonymous artists.

The transformation of cities by modern graffiti began in the 1970s in New York, a city whose extremes provided a fertile ground for graffiti art fusing different cultures and classes. Pioneering artists such as Taki 183, Julio 204, Cat 161, and Cornbread—who painted their names on walls and subway cars in the Manhattan area—gave birth to American graffiti, which then attracted millions of young people and swept the world, and which is now abundant on the walls of every major city.

However, graffiti, drawings, and inscriptions carved into or painted on walls have been around for much longer. Yet what is (or was) not at all clear is that they can (or should) be preserved. The first photographer who thought it worthwhile to conceptually document this type of street art was Hungarian-born Brassaï (born Gyula Halász, 1899–1984). He spent three decades wandering the streets of Paris, and in 1961, published a book of the drawings and scribbles he photographed, entitled Graffiti (although they are only partially identical to the type of graffiti we see today). Lugo, who similar to Brassaï was a chronicler of a city, followed in his footsteps, and by capturing graffiti, they brought it officially into the realm of recognized art.

In addition to Lugo’s three hundred and fifty images, the album explains the basic concepts of graffiti, its various styles, legal aspects, the most important graffiti lines in Budapest, and includes interviews with four Hungarian graffiti artists—Floek Uno, Trans One, Fat Heat, and Jok13. The book is a unique piece of work in terms of both its visual and textual content.

The album was produced jointly by the private art collection of Tibor Jakabovics, the Budapest-based Equibrilyum Art Collection, and the Equibrilyum Book Publishing House, edited by Boglárka Cziglényi (cultural manager), János Kurdy Fehér (curator, poet), Blanka Lugosi (art manager, successor) and Szabolcs Szilágyi (SI-LA-GI, visual artist), based on a book design by Gábor Gerhes (visual artist, book artist).

Residential area from Prague’s old port

Brutalism and personal stories in the spotlight | Film and Architecture Festival 2022