Zsófia Kollár, a Hungarian designer who is living in Amsterdam, moved to the Netherlands because of her studies nine years ago. Her Human Material Loop project, in which she explores how human hair can be integrated into the textile industry, has been covered by international news sites. More recently, Zsófia has published a book in which she also thematizes overconsumption through a very specific filter, the objects’ cultural history and their identity-shaping effects. We asked the designer about her professional journey, her recently published book and the Human Material Loop startup.

How did your design career start and how did you end up in the Netherlands?

I graduated from the Buda Drawing School as a jeweler. I didn’t have a vision of what I could create in Hungary. I saw that Hungarian design couldn’t grow at such a pace as I would like to develop myself and other political-economic factors were also influential in my decision. Thus, in 2013, I started university in the Netherlands, completing my bachelor’s degree in Interior Architecture & Furniture Design at the Royal Academy of Art in The Hague and my master’s degree in the Radical Cut-Up program at the Sandberg Institute in Amsterdam. Even at the bachelor level, I was much more interested in the materials themselves and the conceptual part of design. I never made a functional object, but I was very much involved in material experiments, which has accompanied me later on. My book Object-Oriented Identity: Cultural Belongings from our Recent Past, for example, was based on my Master’s thesis on how different materials represent our identities and, in this context, how brand communications, advertising and social media manipulate our perceptions.

It is also relatively easy to see from the Central and Eastern European region that critical thinking and speculative design play a key role in Dutch design education. What has been your experience with it?

Yes, speculative design is important here and designers get a lot of space to explore different themes. This is also the result of the fact that in the early 2000s, Dutch designers laid the foundations of product design and little room remained within this for renewal.

The design society in the Netherlands has become more of a thinking society than a product-oriented one.

At university, for example, it was never the end of a project to sketch out what you could design perfectly, ready for production, it was always more about the process and how you were thinking about design.

You mentioned that your book is based on your thesis. Did you apply for the Master’s program already with its research topic?

No, in fact, the Master’s program also came quite unexpectedly. I was thinking a lot about what I wanted to do after my bachelor’s degree. Although I applied for several courses, I didn’t want to start them, but I was accepted for a temporary program that only runs once, and I couldn’t pass up that opportunity. The basic premise of the Radical Cut-Up program was that authenticity no longer exists today, we are shaped by different information and knowledge, and everything is essentially like a collage. We all came to the program from different backgrounds; I had an actor, a graphic designer and a VJ teammate. I became really enthusiastic during the research; I couldn’t get some chapters of my thesis accepted because they exceeded the character limit and after graduation, I added more chapters for publication.

Since publishing isn’t the most popular activity to raise money for, I started an Instagram page as well—even before I got the funding—so that I would have a base in case I needed to promote the idea for community funding. (The page now has more than ten thousand followers—Ed.).

What does your book offer to readers?

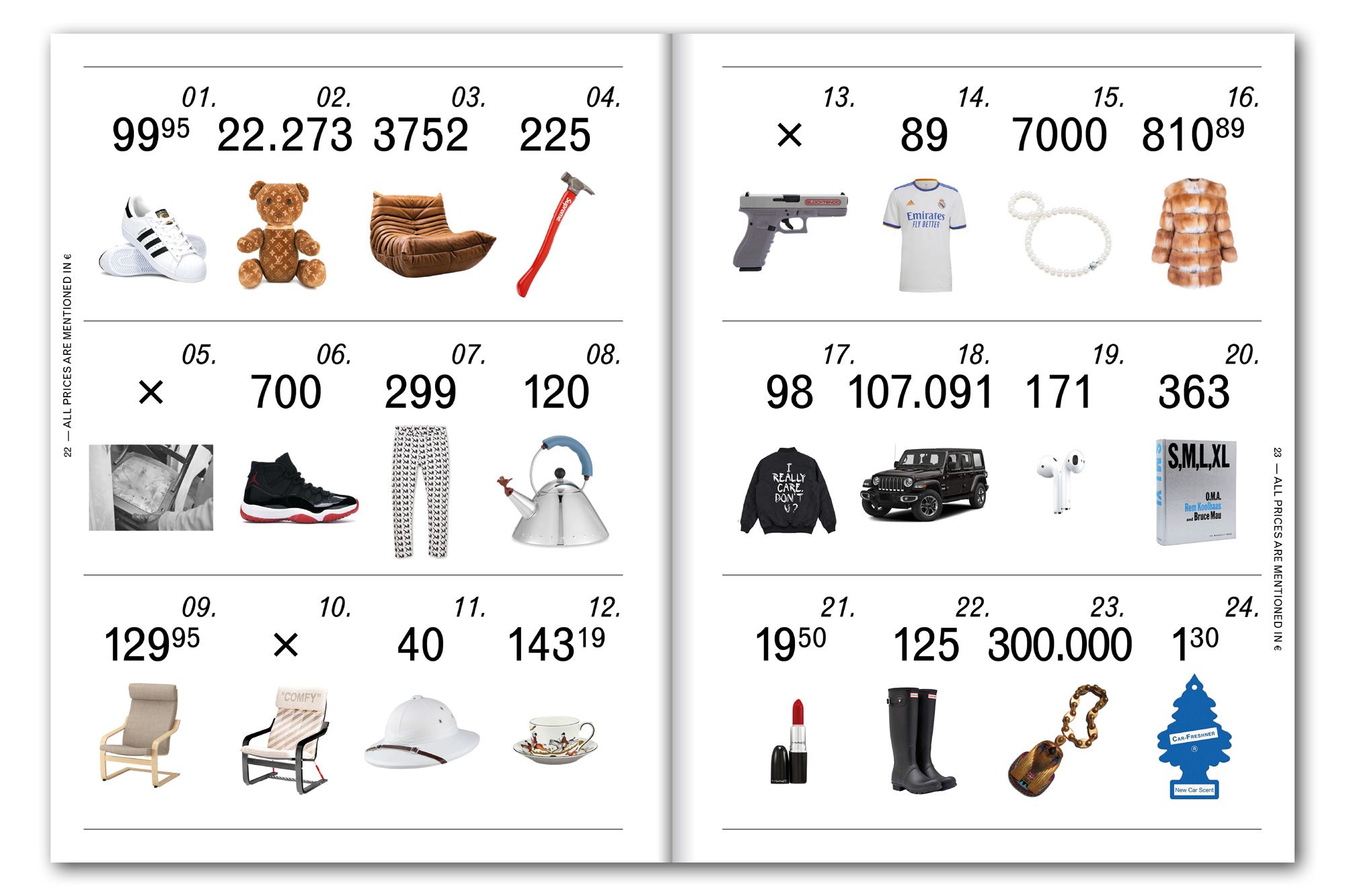

The book begins with five chapters that analyze the concept of identity, the logic of global capitalism and consumption, advertising, social media and the role of semiotics. This introduction shows what identity means in contemporary culture and what shapes who we are. Interestingly, people know all about the latest collections from fashion brands but little about what we celebrate at Easter or what Americans celebrate at Thanksgiving. Our knowledge has taken a completely different direction. Social media manipulates us; we are slowly turning into advertisements ourselves. Our clothes represent us.

I didn’t want to give a harsh critique; the book is more about how we can approach an object with different eyes at the moment of shopping—do we buy something because it has a logo on it? Or because it was worn by a celebrity? I analyze many different objects in the book, mainly from a cultural-historical perspective. For example, it’s interesting how jeans were initially a symbol of the working man, but after the fall of the Berlin Wall, they became a symbol of Western freedom. Today, it is hard to find quality jeans; most of them are made of polyester and will never decompose.

Another exciting example is Alessi’s products, which have shaped how we think about design. While they do an excellent job, it is also interesting to observe how their objects become set pieces on the stage of our own everyday lives.

Then there are the cars, for example, the Jeep, which has moved from the military field to the urban environment, into everyday American life. Although, in many cases, it is completely unnecessary to drive such a large, heavy vehicle on the road, yet, the idea that it can conquer the world has become important to people.

How has research affected your everyday life? Has the critical theoretical approach somehow become part of your daily life?

I changed a lot during the research. Not that branded pieces used to excite me, but now I won’t buy a single garment with a tiny logo. I don’t want to be represented by brands. Apart from shoes and underwear, I don’t buy anything new; I buy everything second-hand. However, I collect many designer items and furniture, but they are always about the stories behind the objects. I bought a chair, for example, which is interesting because it’s the first chair that was designed by a woman and went into production. I’m more interested in the historical aspects of the objects than, for instance, the fact that Kim Kardashian posed on a Tom Dixon-designed chair.

The Human Material Loop is another large-scale project in which you are experimenting with the use of human hair. At which stage is the work at the moment?

It’s in the early stages, we’re working on it, and right now, it makes up a big part of my work. The project has grown into a startup, where we are all trying to find ways to recycle hair waste back into the textile industry. We’re in partnership with several factories and engineers, jointly researching and developing how to make the material usable on an industrial scale.

The two projects may seem very different at first glance, but in fact, both the Human Material Loop and the Object-Oriented Identity are inspired by the same idea. While researching the textile industry and overconsumption, I learned a lot about the problems the world is facing today. Human Material Loop is a solution that can make a real positive change and influence consumers’ thinking. While in Object-Oriented Identity, I was exploring individual responsibility and choices, with the Human Material Loop project, I want to put humans back into the ecosystem and into a position that assumes that, in many ways, we are equal to the rest of the living beings on the planet.

Studio Zsofia Kollar | Web | Instagram

Human Material Loop | Web | Instagram

Object-Oriented Identity | Instagram

A fashion brand about the Georgian way of life

The embrace of nature—Fabulous public parks in the region | TOP 5