Alluring female figures, mysterious landscapes, floral ornamentation, stylized cityscapes, and geometric shapes. It was not so long ago that tobacco packaging was characterized by artistic design and refined elegance. The virtual Tobacco Museum (Dohánymúzeum) collects and presents mainly the products of the Hungarian tobacco industry. We asked Balázs Hornyák, the museum’s founder and operator, about his collection, his favorites, and the design of tobacco products.

How did you start collecting and how did you launch your tobacco museum?

It started as a hobby, collecting empty cigarette packets, but I managed to collect quite a lot of them in a short time, so it wasn’t that interesting anymore. My general fascination with the past led me to investigate what cigarettes existed in our parents’ time. The collection grew from flea market and antique shop hunts, but it was not easy, because a cigarette is not a work of art, a painting or porcelain, made to be collected and treasured, but a utilitarian object that is destroyed when it is no longer needed. This is exactly what makes this area so interesting. What are the chances that a packet of cigarettes will not be consumed and will survive for decades, even through wars?

Not much, but as it turns out, it is sometimes possible. Tucked away in coat pockets as a moth deterrent, or dropped behind a drawer, a packet can escape, and sometimes entire collections from the past are recovered. A pack of Magyar pipadohány (meaning ‘Hungarian pipe tobacco’—the Transl.) made in 1918 in Kolozsvár was found during the demolition of a house, the carpenter accidentally forgot it on one of the beams, so it was boarded up. There it waited for ninety years. Similar stories and countless other interesting facts can be found about the history of tobacco in Hungary. After having collected since 1998, I felt in 2010 that I should share the treasures I had found with others. And thus, the virtual museum was born.

How do tobacco product designs reflect different shifts in society and aesthetics?

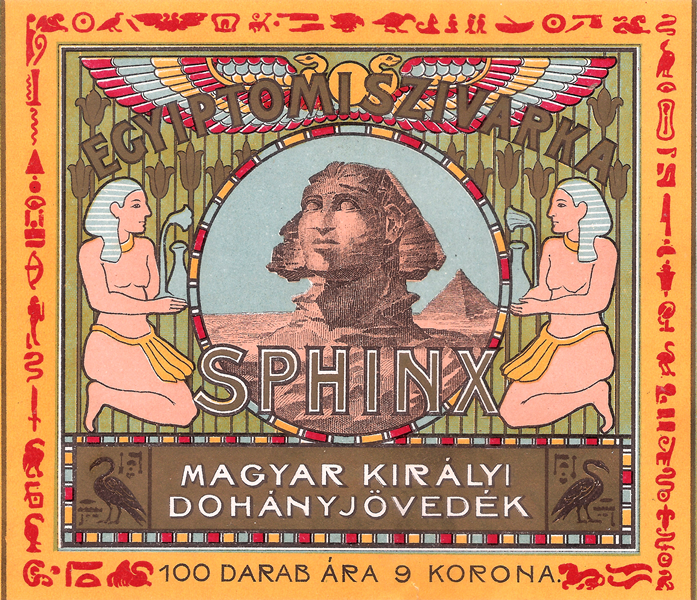

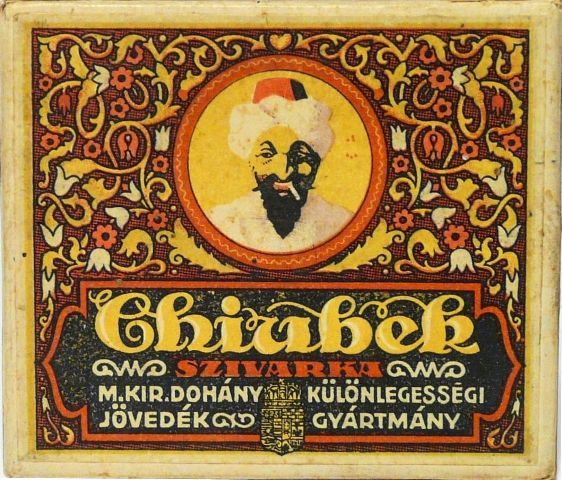

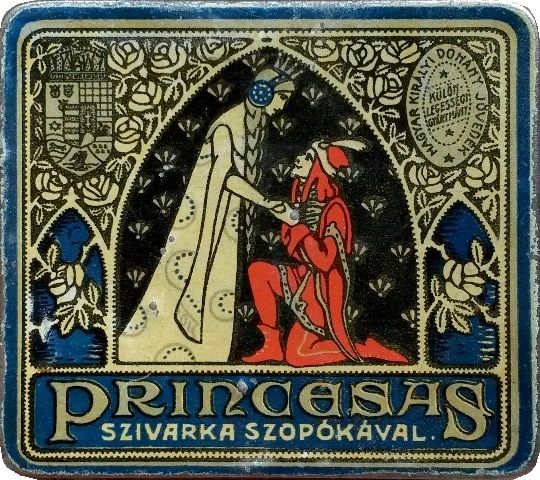

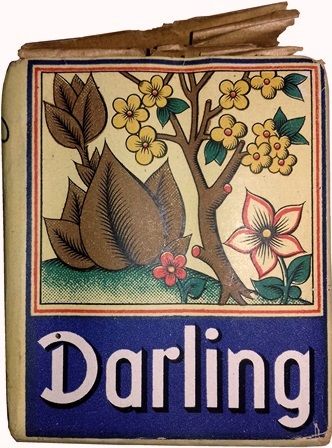

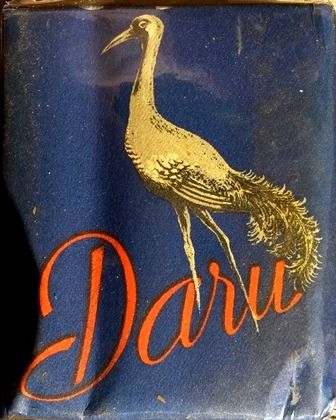

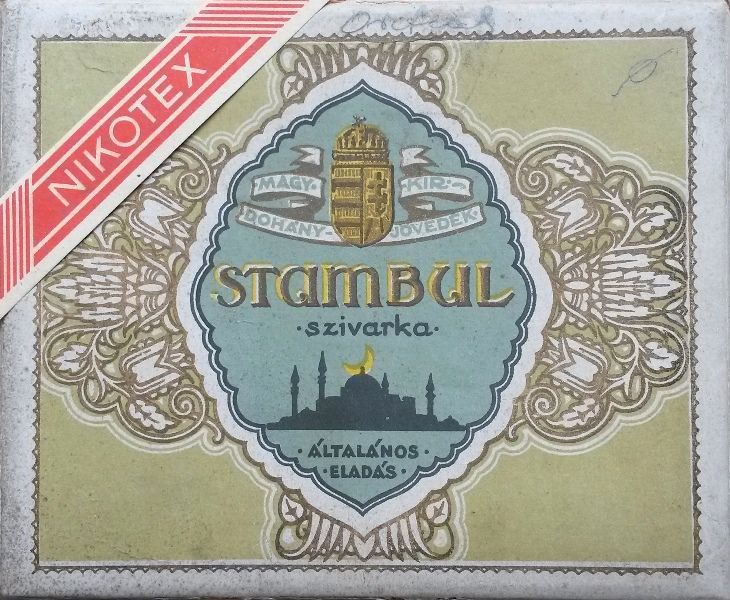

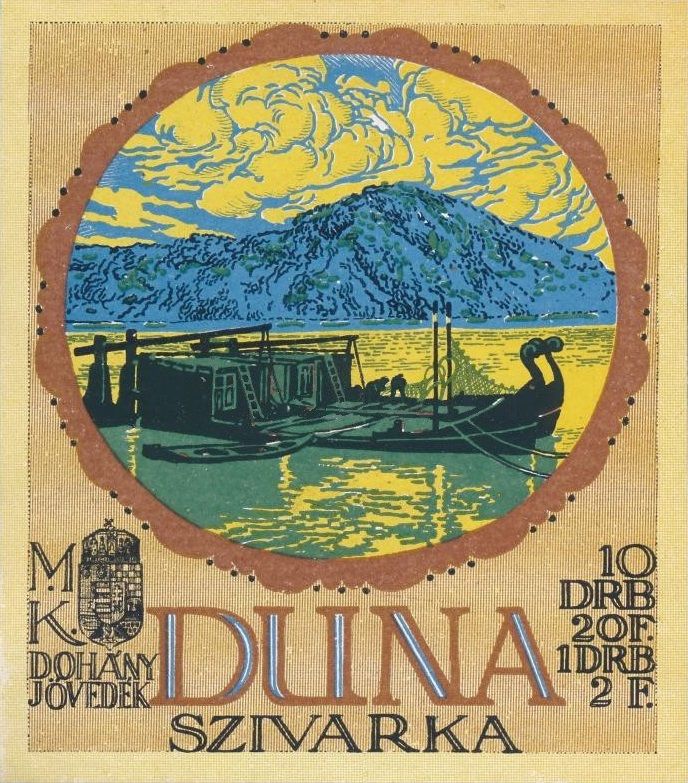

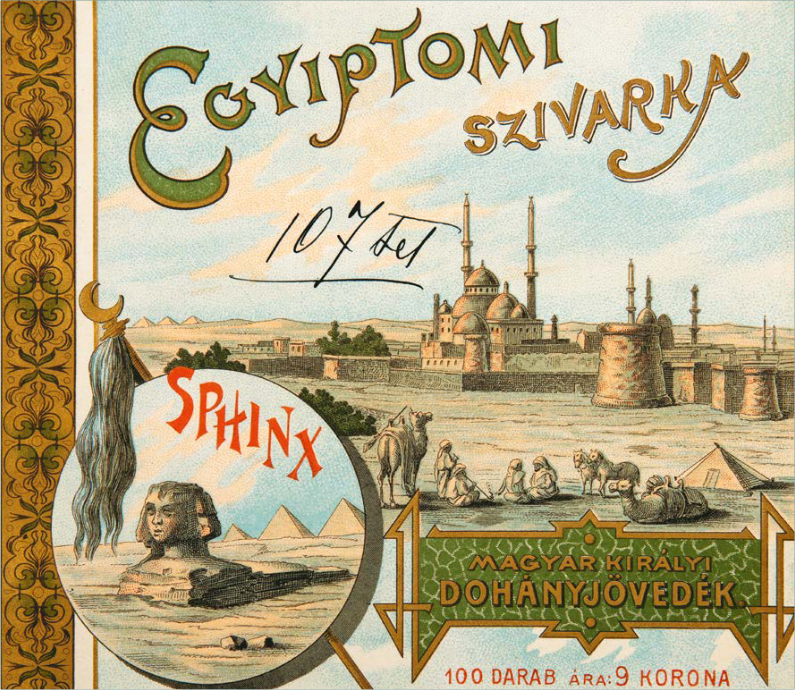

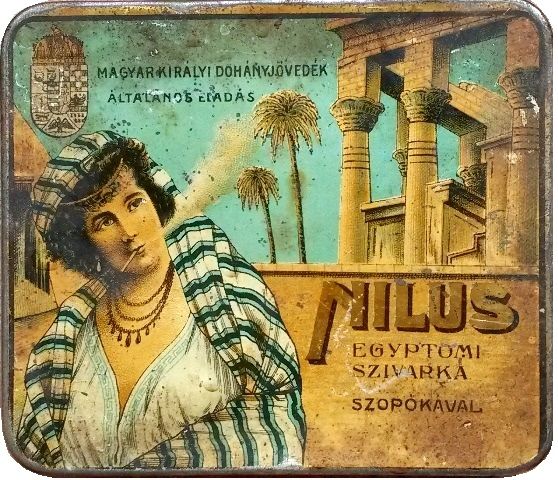

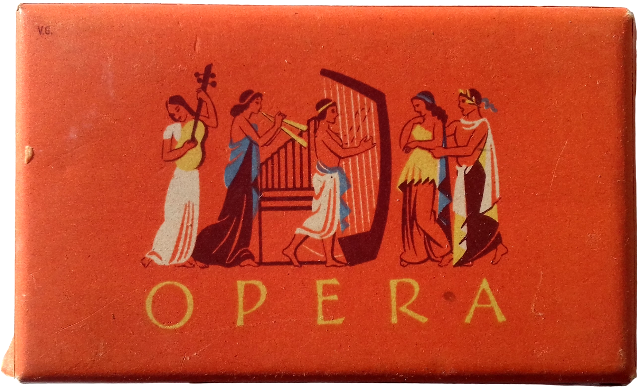

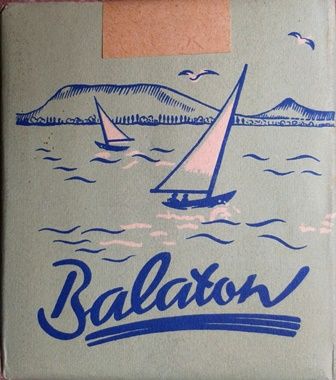

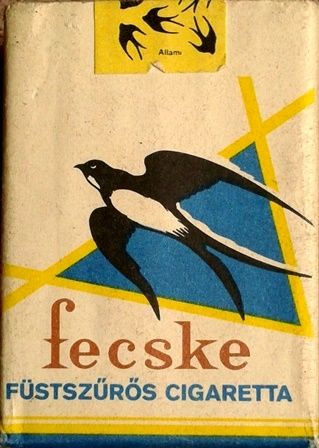

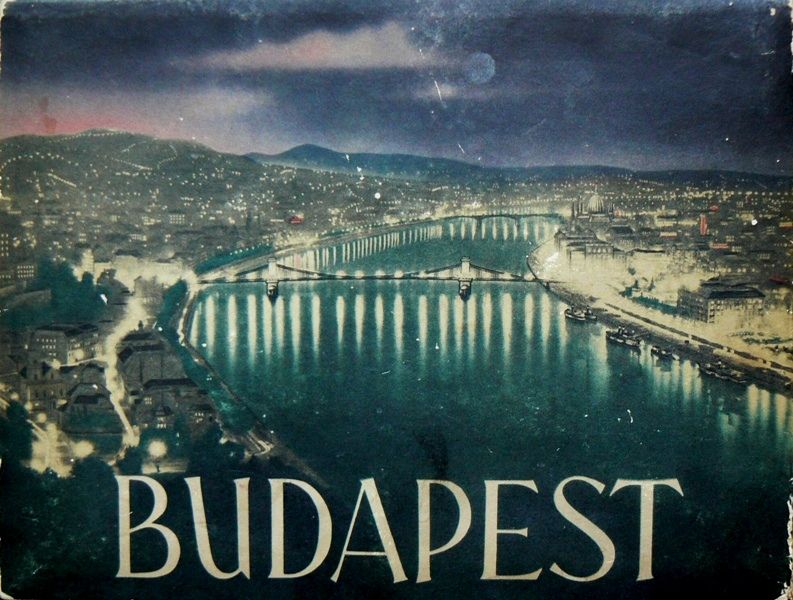

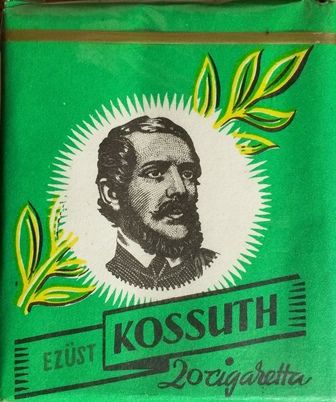

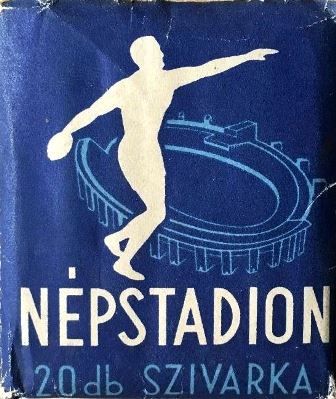

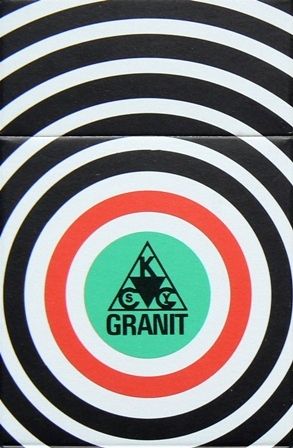

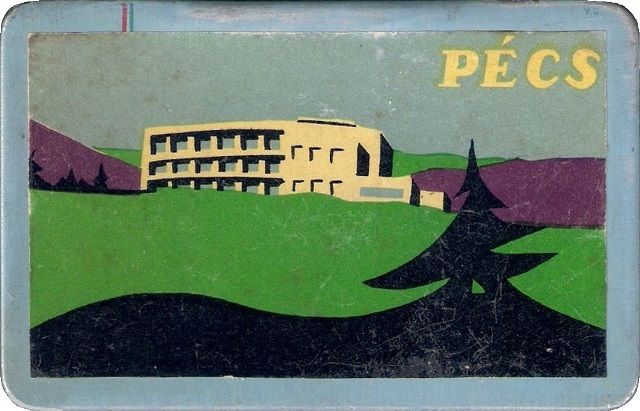

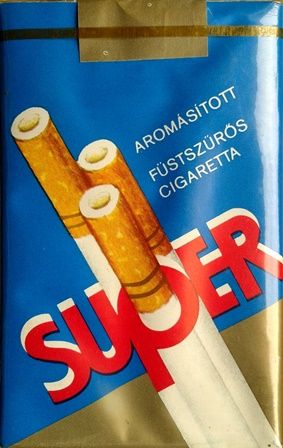

It’s relatively easy to identify a piece of clothing or an object by the stylistic characteristics typical of a certain period. Thanks to industrial design, the history of the last hundred years, along with artistic trends, is reflected in the packaging and names of our tobacco products. At the turn of the century, Art Nouveau was all the rage: wavy ornamentation based on floral or geometric patterns, bold, bright colors, everything rounded and curved. In the 1920s, a new stylistic trend began to emerge: Art Deco, which can be traced back to Art Nouveau, but also incorporated some of the characteristic elements of the avant-garde, resulting in straight lines and geometric designs. After the war, a sad change took place, with the former elegance and meticulous taste being replaced by a pathetic simplicity. And from the 1960s onwards, a plethora of stylistic features of Socialist Realism—curved shapes, geometric figures, handwriting-like typefaces—took over.

At one point there was a strong Egyptian theme (as in the case of cigarettes called Fáraó or Memphis). Why did that happen?

Egypt is essentially unsuitable for tobacco production. As the tobacco there was of very poor quality, its production was banned. On the other hand, the climate is very good for drying and processing tobacco, and labor was cheap, so before the turn of the century, many cigarette factories were established there. Thanks to British soldiers, their excellent products reached England and soon became world famous. The Hungarian tobacco monopoly was piggybacking this reputation by giving its products such names. On the other hand, since people at the turn of the century were fascinated by the idea of Egypt, the excavations and discoveries that took place there, the ‘mythical East’, I think it was also a kind of advertising ploy—with such names it was easier to sell products, people expected some special secret from it.

Which is your favorite product or era?

I have several favorite pieces, but my favorite era is pre-WWII. At that time, tobacco packaging often carried artful masterpieces, designed with the utmost meticulousness by renowned graphic designers and artists. It is also amazing to me the quality of printing achieved with the techniques of the time, and the quality of the boxes is impeccable. There are no poorly fitted or glued boxes, no misprinted graphics, and even the cigarettes are richly decorated and gilded. Favorite pieces are the blue Darling and a cigarette sample collection. From later times, the Balaton and the Mentha. Most distant from me because of the ideology it represents, but still worth mentioning as an important curiosity, a pack of cigarettes with a swastika, of which I have never seen another, not even from foreign collectors. It is strange that it survived, as cigarettes were considered currency during the war.

Is your collection still growing? What is your latest special acquisition?

Since my collection now numbers nearly 2600 pieces, it is, unfortunately, becoming increasingly difficult for me to find something that is still missing, but of course, it is not impossible. I know a lot of brands from other collectors, from foreign sites, that I don’t have. Despite this, there are often items that turn up that I have never heard of or seen. I keep a list of every item I come across, and so far I know of about 8,000 tobacco products with different graphics, different packaging, or different presentation manufactured or distributed in Hungary. This number does not include imports that appeared from the 1970s onwards (Dunhill, Peter Stuyvesant, St. Moritz, etc.), nor the thousands of international brands produced by the privatized Hungarian tobacco factories following the regime change (Marlboro, Multifilter, Pall Mall, etc.). There are many of these, and the collection is already endless—both financially and in terms of storage space. Some kind of limit had to be imposed. The most recent interesting pieces are not so old, but their absence has been frustrating, as I have seen them turn up several times at auctions, but either I missed them or they were unrealistically expensive. Now I finally have two types of Bányász (meaning ‘miner’—the Transl.) cigarettes from the early 1950s. I would have preferred pre-war ones, but they are very rare. Interestingly, when they do turn up, it’s usually the same variety.

Today you can get tobacco in the most appalling packaging possible (at least in our culture). Do you think there will ever be another eye-catching design for tobacco?

I personally find uniform packaging very irritating and terribly hypocritical. On the one hand, I think it goes against all competition rules, and on the other, I don’t think it has much effect. I would even go so far as to say that if you see rotting lungs and corpses dozens of times a day, it is there in your subconscious mind—and since you cannot or will not quit, it only increases your guilt or may even cause the disease itself. I don’t think it is likely that there are fewer cancer patients in countries with plain packaging, or more where there are nice cigarette packets. Every smoker knows that it is a harmful habit. I see no chance of this situation improving in Europe, in fact, I think it will get much worse.

Be sure to watch these Eastern European films! | TOP 5

The new taste of a mission—ZIRP