Visual artist Luca Markó graduated from MOME (Moholy-Nagy University of Art and Design—the Transl.) in 2018, with a degree in Media Design and today she is the happy mother of a little girl. On her Instagram page, she shares her analog photos on a daily and weekly basis, through which one can almost feel the mystical, yet self-evident naturalness of the mother-child relationship. Her work was recently featured in Photo Vogue’s Mother’s Day selection as part of the Eye Mama Project. In our interview with her, we talked about photography, motherhood, and the dual balance of the two.

Before art, you studied aesthetics. How did you go from theory to practice, more specifically to photography?

I knew when I was about 17 or 18 that I wanted to be involved in art, and more precisely the creative part of it. When I didn’t get accepted to MOME after my graduation, it was very clear to me that I wanted to study liberal arts. On the one hand, I had an interest in that direction, and also, because my parents had both studied liberal arts, there was a certain coziness to it. It was kind of in the air that I wanted to go in this direction. Then I attended MOME’s Media Design department, earning both a bachelor’s and a master’s degree, and by the third year, I knew what I wanted to focus on. Even then I was already attracted by more personal or women-oriented themes, but I also made video installations or objects during this time.

Six months after graduating, I started to focus exclusively on photography, and then the real breakthrough came with analog photography. I had already used damaged Polaroids in my diploma work, so I had this interest in experimenting from earlier, and I had wanted to shoot analog for a while, but somehow I only found enough time and space to try it when I became pregnant. It was then that I looked at the photos taken around the time of my birth and documented my own pregnancy with the same camera that was used to capture those images.

How did motherhood influence your relationship with photography? What attracted you to the analog medium?

It gave me a much more concentrated, flow-like experience which for some reason digital photography just couldn’t. It has unleashed a ton of energy in me. As my belly grew, I was able to do fewer and fewer things; but when it came to photography, even at seven months pregnant, I was still climbing fences or entering abandoned properties. For some reason, it has given me a lot of strength, energy, and motivation. Also, I really love the anticipation that is inherent in this type of photography, and this has also resonated well with the pregnancy itself. And since then I have been shooting almost exclusively analog. Somehow the visual world that this technique offers is much closer to me.

A cohesive visual world is revealed through your work. How do you compose your images? Do you plan them in advance or do you play with the power of chance?

Photography is completely integrated into my everyday life, there is no time when I am not taking photos. I take analog pictures every week, but planning plays a very big part in it. I often think in pictures: compositions flash through my mind and then photos are born. On the other hand, I watch and observe phenomena, which I also write down. It was typical of my earlier work as well that the initial phases were in this sense done in a “notes folder”, which allows me to better capture the moment when it is happening.

My series of photographs start spontaneously: in lesser part, they are made up of candid, diary-like images; but sometimes a theme, a life situation will find me. Then I consider whether it should become a photo series. Then I give myself clues and internal rules that also give a framework to the projects. These can then change from series to series, but the footage of the last three and a half years, the multiple series on motherhood, are also interconnected. In principle, I also think in series, which have a starting and an endpoint in my head. But in certain situations, I’m particularly fond of happenstance, even slip-ups or defects. For example, I have a separate collection of my pictures that are were somehow damaged during the analog process. But these are also often the most exciting pictures, both in terms of color and subject matter. I love these mistakes and this combines well with the fact that I can’t foresee what will come out of a roll, so I am also surprised by the end result.

We get a sensitive and intimate insight into your everyday life. How do you decide what to keep as personal memory and what to share with others through your images?

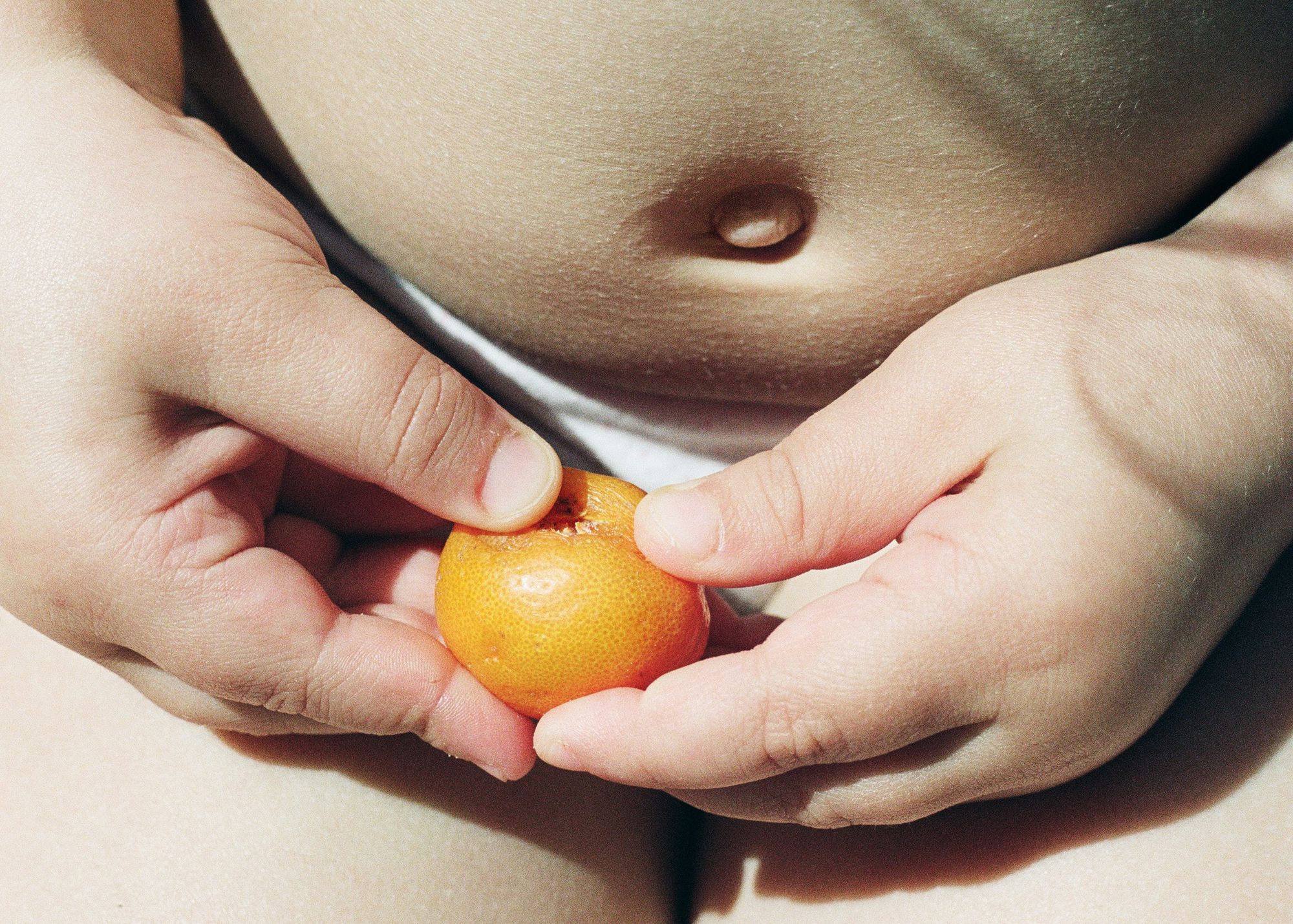

Precisely because I think beforehand about what I want to include in a series, or it is preceded by a curation, a long thought process, I usually have no problem deciding what to show and what not to show. I feel like I know my limits in this. For instance, a lot of my images show my own body or body parts, whether it’s milk spurting from my breasts or amniotic fluid on a hospital bed; not as a beautiful body in the classical sense. However, on one hand, they get detached from me—perhaps due to this awareness—once I make them. On the other hand, in a world of horribly sexualized or over-sexualized bodies, I think it is very important to encounter such images: real bodies, real women’s bodies in transition. Also on a personal level, I am quite fond of this type of series.

What causes a bigger dilemma is showing my child. But I think we need these kinds of images that show this period first hand, through the eyes of a mother. So that we don’t just see an idealized world, as is often shown in private photos: a family standing with everyone smiling, or pictures taken in the studio, and so on. But with my little girl, I’m more conscious, I often only show body fragments, and there are times when a picture doesn’t make it to Instagram, but only into an art album, or showcased in an exhibition. I feel like that’s what makes it work, if I show real bodies or if I truly let the situation get close to me.

The objects we surround ourselves with speak volumes about us. Your own home serves as the setting for most of your photographs, so your objects become important elements in the images. What is your relationship with them? Have you always been interested in material culture?

It is often said that you shouldn’t be too attached to objects, but for me, they are particularly important and especially those that store or evoke memories. For example, I really like writing desks and bookshelves in other people’s homes. I often ask their permission to photograph these, because for me they are linked to a sense of homeliness. I enjoy observing other people’s objects, and their surroundings; often when I take photos I want to show this space of home. When I’m not my own model and I have the opportunity, I like to show people’s personal spaces, even through portraits. Besides this, I also have a fascination with heirlooms. In our apartment, we cohabit with some of my great-grandmother’s objects. I love this type of contrast or blend, when the new and the old are juxtaposed. I also like objects that have a flaw, that are unique, that are irreproducible.

Will we see more images from you in the future that focus less on your own micro-environment and more on the outside world?

I think that the main thrust of my work will always come from a personal connection, simply because these are the subjects that I like to work on, even for years, and the ones that I have in my head. Perhaps that’s why my work can be categorized as personal photography, because I also present a variety of more universal themes through my own filter and life situation. For example, right now I am working on a series that deals with the theme of distance from nature: the climate crisis, motherhood and nature; but in this one too, the personal perspective is present. It is similarly important for me to step back from a work and look at it from a more distanced, social context. I am also working on another series: I want to photograph fifty mothers in their homes. For this project, it is greatly important to show as many stories and situations as possible, which is also a step back from the personal aspect that characterizes my series.

What foreign Instagram sites and magazines do you collaborate with, and how did these relationships develop?

I found the Eye Mama Project during the coronavirus epidemic, which was a startup platform at the time. This site gives visibility to artists who document their everyday life and their motherhood. At first, it wasn’t even apparent how it would turn out, but since then it has gained more and more visibility. I believe that today, grassroots communities and small groups like this have a lot of power through social media platforms. I think this is a very positive trend because I feel that there has definitely been a shift within the art scene—which is, let’s face it, very male-centric—where the female perspective, and in recent years the maternal perspective as well, have become much more prominent.

Touchable dessert experiences | The collaboration of Naspolya Nassolda and Renáta Zsiga