Christopher Nolan’s new film tells the story of theoretical physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer and his role in the development of the atomic bomb. The latter, of course, required many other scientists—many of whom came to the United States from Central and Eastern Europe.

Throughout the twentieth century, many great scientists from the Central and Eastern European region came to the United States, though in many cases not of their own volition, but rather to escape the lack of scientific research and opportunities, and increasingly oppressive and violent antisemitism. In any case, many of them contributed to scientific and technological advances in fields ranging from computer science to medicine—and, of course, played a major role in the invention of the atomic bomb. Nolan’s film features five scientists from Central and Eastern Europe who were involved in some way in the famous Manhattan Project.

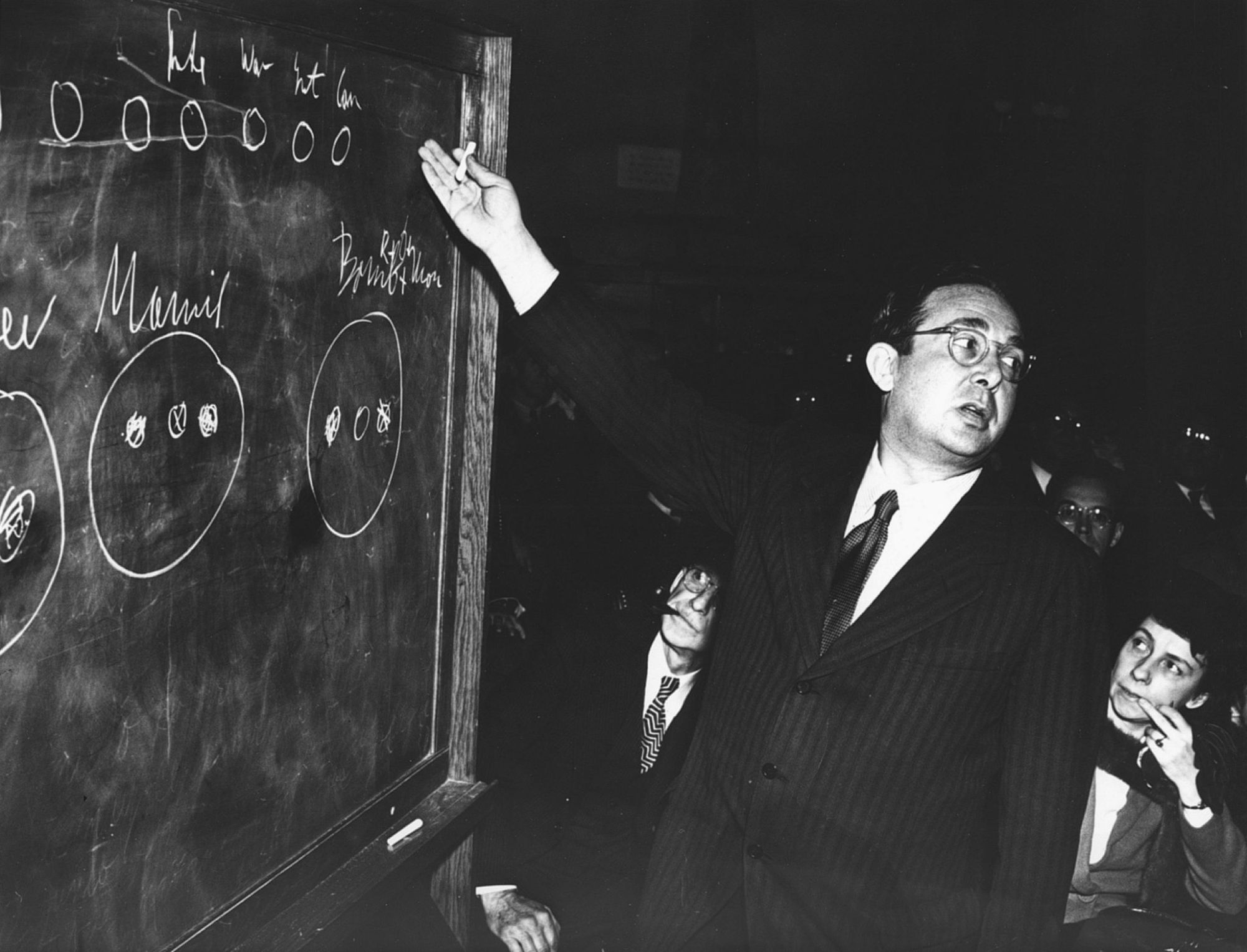

Leo Szilard (1898-1964) was born in Budapest. He studied in Germany in the early 1920s, where he was taught by Einstein, among others, and conducted his research until the Nazi takeover in 1933. He was the first physicist to discover that the nuclear chain reaction, and thus the atomic bomb, could be created. He was already living in the United States when he persuaded Einstein to write a letter to then-president Franklin D. Roosevelt urging him to be the first to create the atomic bomb, rather than Germany. He became a member of the Manhattan Project team and was actively involved in the development of the atomic bomb—the first self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction was developed with Italian-born Enrico Fermi, thus creating an important component in the production of an atomic weapon. However, Szilard later started a petition to stop the US from dropping an atomic bomb on Japan. Although many prominent scientists signed it, it did not reach President Truman; Oppenheimer, incidentally, did not support it and even dissuaded Edward Teller from supporting his compatriot. After 1946, the Hungarian scientist concentrated on biology instead of physics.

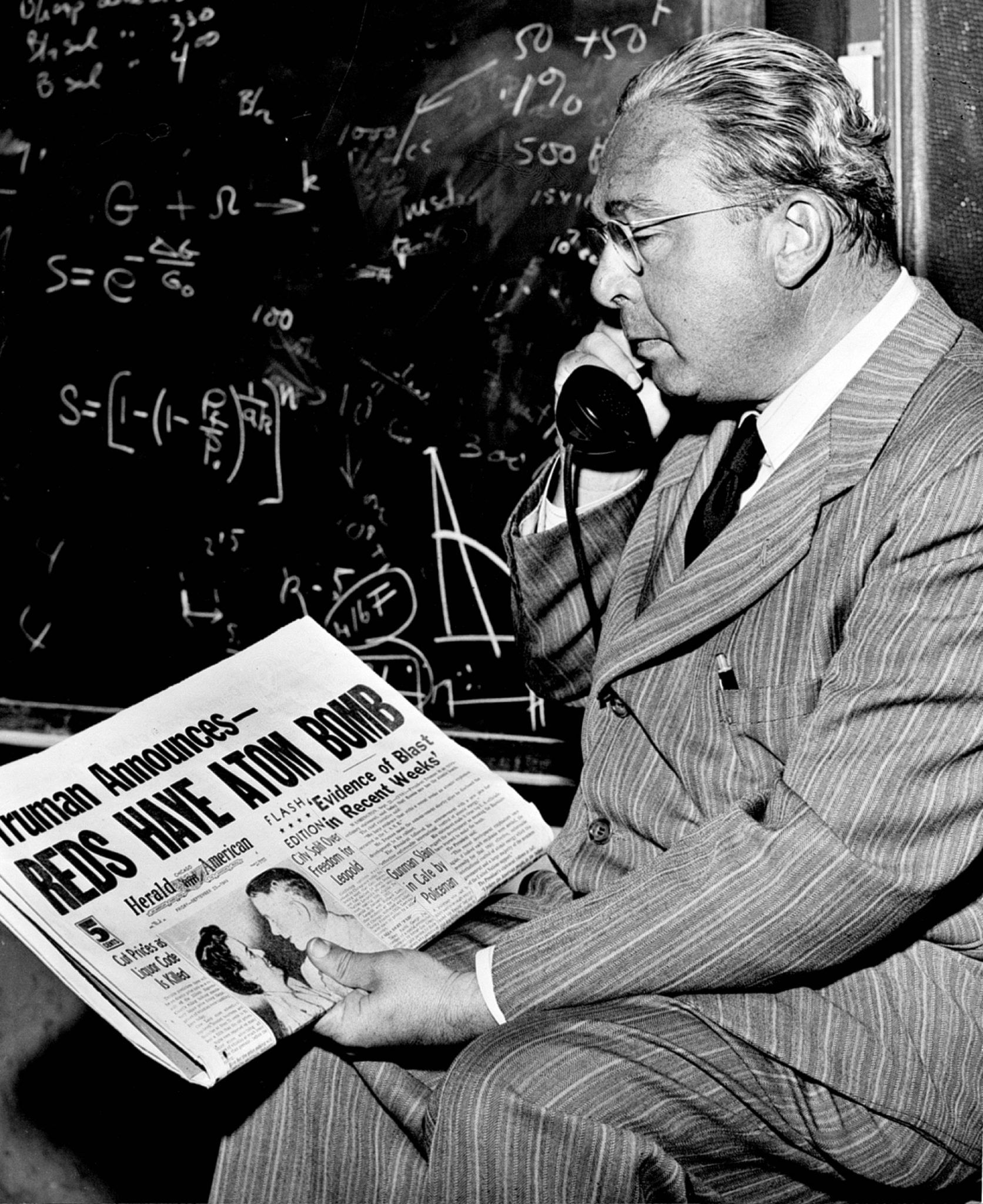

Edward Teller (1908-2003) was born in Budapest. He left Hungary in 1926, studied in Karlsruhe, Munich, and Leipzig, and received his PhD under Heisenberg in 1929. He emigrated to the United States in 1935, obtained US citizenship in 1941 and joined Enrico Fermi’s team. He then accepted an invitation from the University of California, Berkeley, to work with Oppenheimer on theoretical studies of the atomic bomb; and when Oppenheimer established the secret Los Alamos Laboratory in New Mexico in 1943, Teller was among the first to be hired. During the Los Alamos assignment, he increasingly moved away from the main thrust of his own research into a potentially much more powerful thermonuclear bomb. At the end of the war, he intended to shift the US administration’s nuclear weapons development priorities towards the hydrogen bomb. The Soviet Union’s atomic bombing in 1949 made him even more determined that the United States should make a hydrogen bomb, and after British nuclear scientist Klaus Fuchs was found to have been spying for the Soviet Union since 1942, President Truman ordered the weapon to be licensed, and Teller was able to continue working on its realization. Eventually, together with Polish scientist Stanislaw Ulam, they succeeded in developing the new weapon, which was successfully tested in 1952: the bomb exploded the equivalent of 10 million tonnes of TNT. (Ulam’s key role in the bomb’s design was not revealed until nearly three decades after the event, according to secret government documents and other sources.) Teller believed in freedom through strong defenses, a philosophy that was reflected in his views on arms control and nuclear policy. He was later credited with developing the world’s first thermonuclear weapon and became known in the United States as the ‘father of the hydrogen bomb’.

Born in Czechoslovakia in a small town near Prague, Lili Hornig (1921-2017) moved with her family to Berlin in 1929, and in 1933 her father had to flee Germany and they moved to the United States. She studied at the University of Bryn Mawr but interrupted her studies for the Manhattan Project. Her husband Donald Hornig came to Los Alamos in 1944 and Hornig went with him. She initially worked on the chemical properties of plutonium but was transferred to the explosives group because of its potential dangers. She was one of the signatories to a petition started by Leo Szilard to drop the atomic bomb on an uninhabited island instead of Japan. After the war, she did her doctorate at Harvard, mainly in chemistry.

Isidor Isaac Rabi (1898-1998) was born in the town of Rymanów, in the former Austro-Hungarian Empire (now Poland). His family emigrated to the United States in 1899. Rabi graduated from Cornell University with a degree in chemistry, then earned a doctorate in physics from Columbia University, after which he spent two years in Europe. During World War II, he worked as co-director of the MIT Radiation Laboratory. He turned down an offer from J. Robert Oppenheimer to become deputy director of the Manhattan Project but became a consultant and made occasional trips to Los Alamos. In 1944 he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics for his ‘creation of the molecular-beam magnetic-resonance detection method.’ After the war, he became head of Columbia University’s physics department. Further research into the properties of nuclear magnetic resonance was later developed for medical applications in MRI machines. Rabi became an outspoken critic of the further development of nuclear weapons, opposing the hydrogen bomb with Enrico Fermi, and supporting the Baruch Plan for international control of nuclear energy with Oppenheimer.

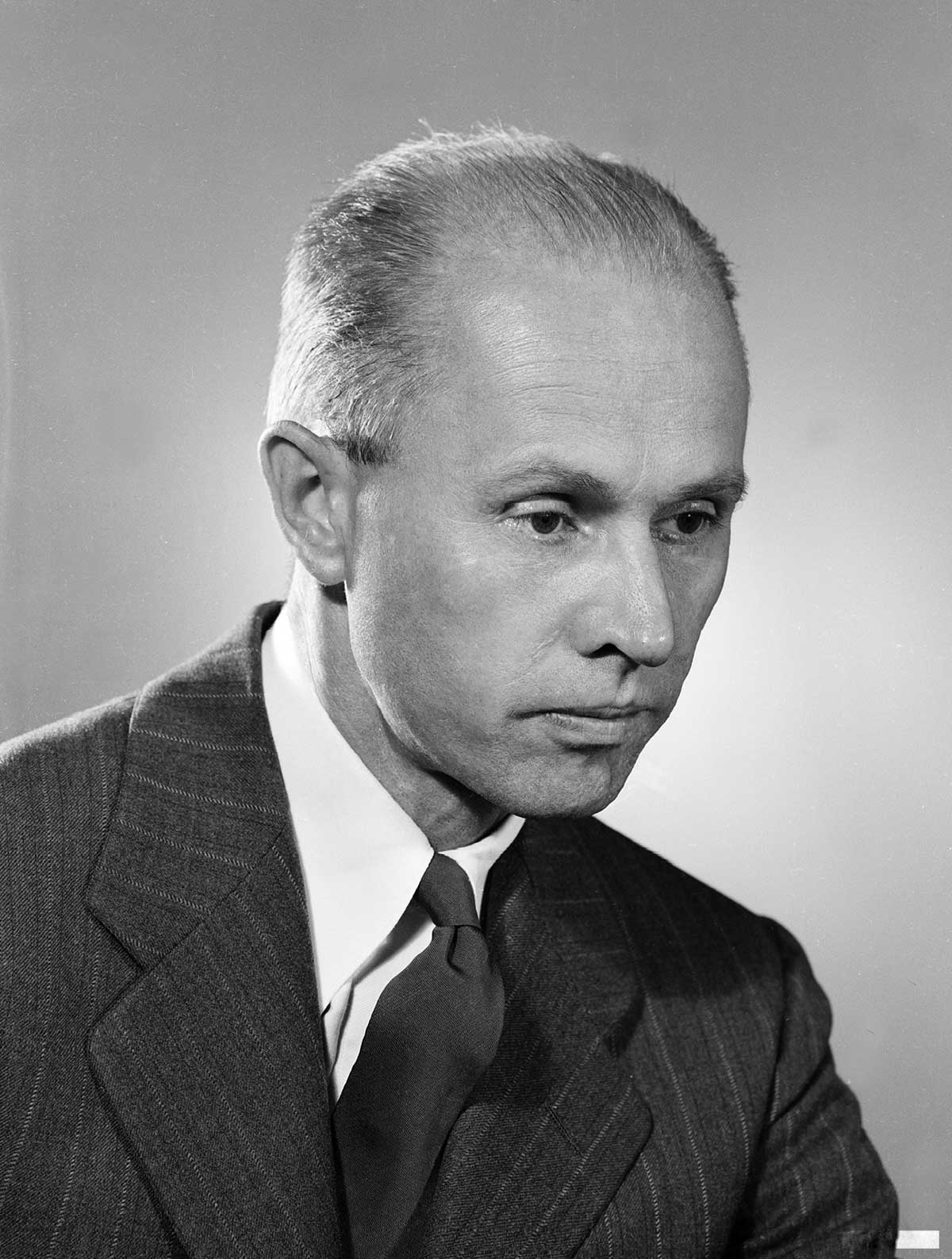

George Kistiakowsky (1900-1982) was born into a Ukrainian Cossack family in Boyarka, in the former Russian Empire (now Ukraine). He fled his homeland during the Russian Civil War, first to Germany, where he obtained a doctorate in chemistry from the University of Berlin in 1925, and then to the United States in 1926, where he became a professor at Harvard University in 1930 and was granted citizenship in 1933. He joined the Manhattan Project in early 1944 in charge of the X Division (Explosives), working on the development of the implosion. After the war, during the presidencies of Eisenhower and Kennedy, he was appointed to the President's Science Advisory Committee and was involved in negotiations on nuclear arms control. In 1968, he cut ties with the Pentagon in protest against the Vietnam War. He worked at Harvard until his retirement.

Sources: ahf.nuclearmuseum.org; Richard Rhodes: The Making of the Atomic Bomb. Simon & Schuster, New York, 1986