The law of the conservation of energy states that it can neither be created nor destroyed, only converted from one form of energy to another. The art of Szilárd Gáspár is an analogy for this process in which human energy is transformed into artistic matter. The artist, creating in the inbetween land of performance and sculpture, breaks away from classic techniques to give a new context to inanimate matter with the expertise of a boxer. How does boxing become a tool of art? In what way can a boxing ring turn from a simple space into an object and a visual metaphor?

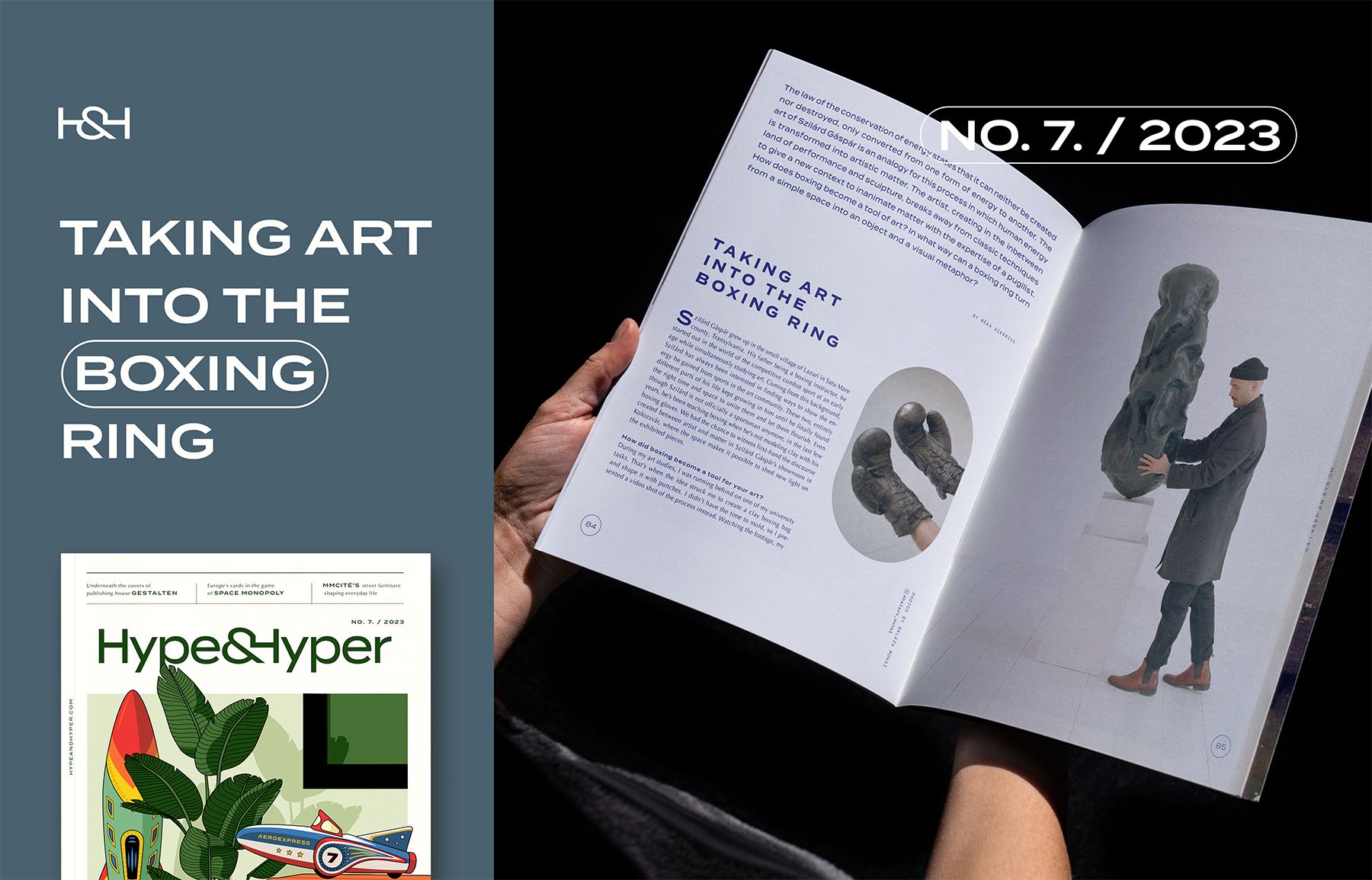

Szilárd Gáspár grew up in the small village of Lazuri in Satu Mare county, Transylvania. His father being a boxing instructor, he started out in the world of the competitive combat sport at an early age while simultaneously studying art. Coming from this background, Szilárd has always been interested in finding ways to show the energy he gained from sports in the art community. These two, entirely different parts of his life kept growing in him until he finally found the right time and space to unite them and let them flourish. Even though Szilárd is not officially a sportsman anymore, in the last few years, he’s been teaching boxing when he’s not modeling clay with his boxing gloves. We had the chance to witness first-hand the discourse created between artist and matter in Szilárd Gáspár’s showroom in Kolozsvár, where the space makes it possible to shed new light on the exhibited pieces.

How did boxing become a tool for your art?

During my art studies, I was running behind on one of my university tasks. That’s when the idea struck me to create a clay boxing bag and shape it with punches. I didn’t have the time to mold, so I presented a video shot of the process instead. Watching the footage, my professors were in awe to experience the emotions invoked by watching a professional boxer punch and radiate energy—to witness the kind of energy created by the expertise and devotion of fighting the punching bag. They emphasised the power of the movement and pointed out how it should be shown in an artistic setting. This was the serendipitous moment when I felt that the two fields united in me.

According to conceptual art, the idea becomes a piece of art, shifting the value of the artwork from the physical object to its concept. How does this work exactly in your art practice? Is it the process itself or the end result that becomes art?

In my works, the process and the piece realised are equally valuable. For me, every performance is like a boxing match, therefore it’s not just during the moment the performance is happening when I react to the matter with the same expertise and devotion, I also pay special attention to preparing my body and mind for the occasion. It’s important for the energy to leave its mark aesthetically on the body during the moment I deliver a punch to the clay.

When preparing the clay, it’s also crucial for it to be in perfect condition to be able to show the energy transferred with the punch sufficiently. It took some time to figure out the exact moment when the clay is the softest or folds the best to create the most expressive result possible.

In most of your performances, you fight alone in the ring. What does a match mean to you in this particular situation?

I used to be an athlete who also did art, but now, I’m an artist who still does sports. I often feel that I’m fighting with myself and the duality inside me: a boxer fighting the artist and the artist fighting the boxer.

How can your art reinvent itself? Have you ever thought about experimenting with materials other than clay?

I’m constantly thinking about other materials to work with such as synthetic resin. During creation, besides the performative conceptual aspect, it’s important to reach back to classic elements of sculpting, for example, to the clay itself. I’d like to give a brand new form to this matter that has never existed before.

Your art practice not only unites performance and sculpture, it also includes photo- and videography. Do you regard these two as ways to document your work or rather as works of art that can stand on their own?

I’d say that the photographs and footage document my performances but are also unique pieces of art. My performances happening in front of a live audience are kept in the moment of action, then they fade away. I believe that this experience can live on in the spectator, meaning, the piece can’t exist in a physical form. These works become fleeting elements only captured in photo or video whereas my molded sculptures are made in my workshop by myself.

Cluj-Napoca is one of the most exciting cities of the contemporary art scene: since the 2007 Biennale in Prague, the local art community has been referred to as the Cluj School. What do you think about the scene in Cluj-Napoca?

When the Fabrica de Pensule (Brush Factory) in Cluj-Napoca—an independent cultural centre that has closed since—and one or two Romanian galleries like Plan B or Nicodim showcased the works of local artists at international art fairs, an even more powerful interest in international collectors, curators and museums was ignited in regard to the Transylvanian art scene.

Even though there are new galleries popping up in Transylvania each year, they are quickly followed by the closing of others. There are only a handful institutions with a constant presence and the ability to stay open. Maybe this is why strong communication flourished among the artists living and creating or studying here and those who have already established their names in the art world. The community tirelessly works on creating a platform for the new generation and by rephrasing it, bringing contemporary art closer to the general audience. Still, the local art community is in need of more galleries and institutions that focus not only on paintings and classic art, but also other forms of art as well...

Photos: Balázs Mohai

Szilárd Gáspár | Web | Instagram

Continue reading in H&H issue no.7!

ORDER HERE

Luxury beliefs: what could replace Porsches and golf?

Vibrant atmosphere at the Spazio Maiocchi bar in Milan