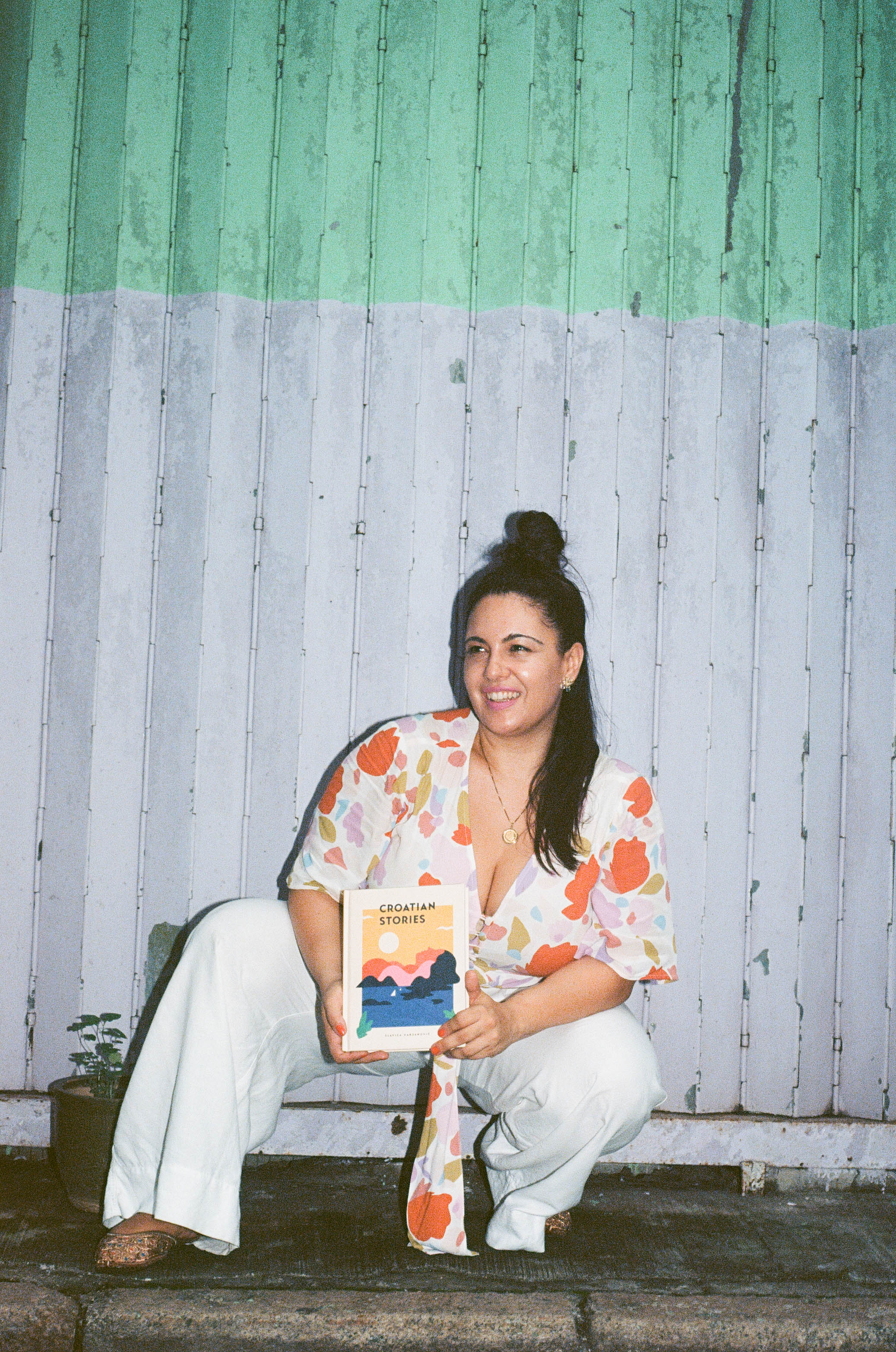

Slavica Habjanović is a Croatian born in Australia, who is now living in China—a curiosity in itself, not to mention that she is also part Hungarian on her mother’s side. What does our origin mean in a foreign culture? Slavica’s book, Croatian Stories, takes us on this journey while preserving small elements of Croatian culture with humor, taste, and respect.

Your personal involvement was what have probably sparked your interest, but can you tell us what exactly inspired you to launch Croatian Stories?

In 2008, I returned to Australia after having lived in Croatia for over a decade and I began working for the Melbourne-based newspaper Croatian Herald. I had a weekly column there called ‘Croatian Stories’. Over the course of 10 years, this column tracked my personal stories and observations on migration, diaspora, identity, life and culture, and idiosyncrasies particular to Croatia as well as comparisons with life in Australia. I thought it would be a nice idea to summarize my column and publish it as a book, as a way of reflecting on and closing out that part of my work. Digging deeper, I realized that my book was connected to the struggle around the world to give voice to the people from smaller cultures and countries, to stories that don’t come from the dominant groups with the most narrative space and power. Croatia is definitely one of those small cultures—and if we don’t stand up and tell our stories, one of two things might happen: either someone else will tell them for us, or they won’t be told at all. These columns are a small contribution to keeping the tapestry of our collective human existence as vibrant as possible.

Who exactly is the book aimed at? Does it build a bridge between Croats in the motherland and those leaving Croatia, or is it strengthening the identity of those living in the diaspora?

The audience I had in mind when I was working on the book was Croats in the diaspora, people traveling to Croatia, and even Croats in Croatia. We’ve had many waves of migration out of the country, so our diaspora is very diverse, and I’m really curious to see how it lands with different people and what they experience. For me, the book is like a flashlight that illuminates those participating in this discourse. The fact that so many non-Croatians have connected with the book was one of the really nice and unexpected things. For example, a Hungarian friend in Hong Kong, unable to travel to Hungary last summer due to Covid restrictions, used the book to relive memories of her childhood beach holidays in Croatia. Another reader from India loved the column on Borovo shoes, which has a connection to the Bata shoe company that she remembers fondly.

You describe charming peculiarities, such as the fact that Croats are sensitive to drafts, but we can also listen to a selection of Croatian music using the QR code. How can identity be preserved in a remote environment?

This is a really great question that I think about a lot. I can’t say I have a definitive answer, but I can offer a current perspective that probably opens up more questions than it answers. Should identity be “preserved”? Or is it rather something that naturally evolves and changes over time?

I think identities shaped by different places and cultures, such as mine, are constantly changing, so personally, I find it more interesting to think about how the elements of one’s culture and identity interact with the world. Context is a really interesting lens through which to view this. For example, in Australia, where there’s a large Croatian community spanning several generations, it’s easier to “preserve” or rather fossilize identity. Besides, the grief that a community experiences when parts of its culture (especially language) disappear or are erased should also not be underestimated. I think language transmission is a key aspect of keeping cultural elements alive, as well as maintaining a direct link with the country of origin.

I recently went through an identity “crisis” that relates to your question. For the last three years, I haven’t been able to visit Croatia due to Covid. I felt a certain loss of connection to a place and some parts of myself that I would call my ‘identity’. It’s been an interesting and quite unsettling experience, making me question what feeds and anchors my identity, and how I fit into Croatian society. Ironically, I published a book at the end of this period, but I’m still processing it.

The visual world of the book is also remarkable, for me it represents both the aesthetics and the nostalgia of Croatian summers. How was this visual world created?

I had the honor of working with an incredible Croatian artist, Imelda Ramović. It was very important to me that the book and all related merchandise be beautiful products that people would cherish and hold for years to come. Imelda understood the brief and the essence of the book from the start, as well as what I’d like visually, and it was the most enjoyable creative process. We definitely wanted a bold color palette reminiscent of summer, which we combined with a slightly nostalgic feel of Croatian posters from the 1960s and 70s. The book wouldn’t be what it is without Imelda’s visual work. The typeface that Imelda has chosen is also worth mentioning—it’s called Zico and was invented by Croatian graphic designer Marko Hrastovec.

If you’d like to read more about Croatian culture beyond Game of Thrones, the beach, and football, follow Croatian Stories on Instagram!

Croatian Stories | Instagram

Getting used to constant distress—daily life in Ukraine

Estonian-Croatian animated film Eeva premieres at the Berlinale