I once had a chat with a Hungarian screenwriter. The topic was Hollywood’s superhero movies, the ones in which Superman or Iron Man saves civilization, sometimes with a Starbucks coffee in their hands. Over a couple of beers, we pondered where our superhero films were and came to the conclusion that the answer lies in our Central European history. János Hunyadi, “Scourge of the Turks”, freedom fighter Tadeusz Kościuszko, or Czech monarch Charles of Luxembourg are all figures who acted as the “Iron Men” of our region, but contrary to their Western counterparts, they didn’t come from the fantasy world but instead shaped the course of our history as real historical figures. Undoubtedly, Móric Benyovszky—the heroic soldier, famed traveler and unparalleled memoir writer claimed as their own by the Slovaks, Hungarians and Poles—has a rightful place on the list of Central European “superheroes”. This article was published in print in Hype&Hyper 2021/2.

Illustration by Gergő Gilicze

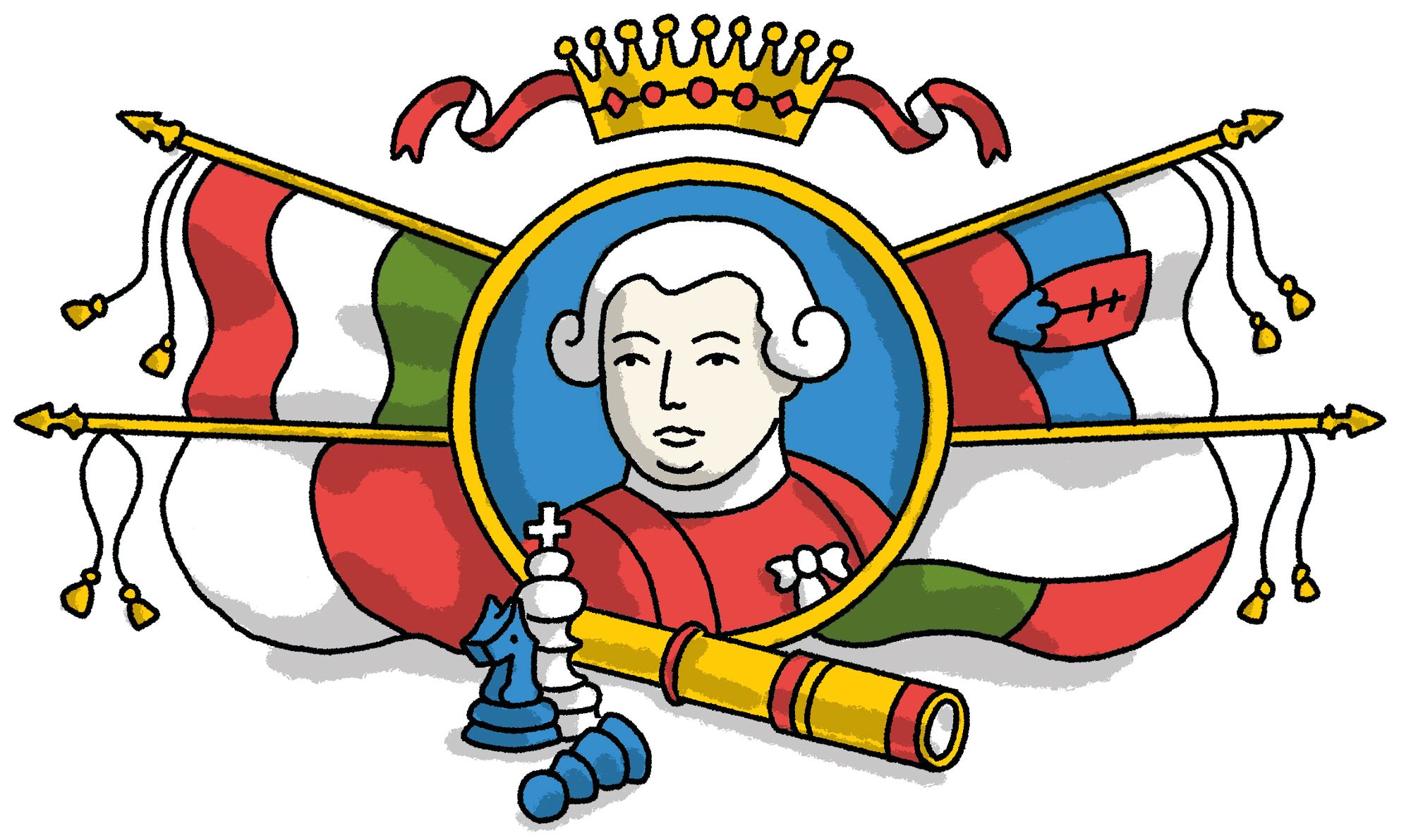

Móric Benyovszky was born in 1741 as a descendant of a noble family in Verbo, in Nyitra County of today’s Slovakia, a part of Hungary back then. The Hungarian noble family with Polish kinship served the ruler in military service, so the career of the young Móric didn’t raise any eyebrows. He started attending military school at the age of 10 and fought in the battle of Levosic when he was only 15. Even though his abilities and achievements showed great promise in the imperial army, Benyovszky decided to settle in Lithuania in 1758. Meanwhile, his father passed away and due to his absence, his relatives cut him out of the family inheritance, which he did not take lightly, and returned in arms to enforce his share. What started out as a minor family dispute eventually turned into a major scandal, as his opponents framed the conflict over the inheritance as high-treason and rebellion in front of the Viennese court, so Maria Theresa deprived Benyovszky of all his property and exiled him from the Habsburg Empire without any actual investigation or evaluation of the circumstances.

Every cloud has a silver lining, and just as Peter Parker became Spider-Man from a spider’s bite, Benyovszky’s exile was the first step on the road of his adventurous life. The first stop was in Poland, where he gained detailed knowledge of shipbuilding, geography, and navy cruisers. In 1767, he took part in the Polish uprising against the Russians, and at Zhvanets, he clashed with Russian forces but was forced to retreat. He recovered from the defeat in Khotyn, Moldavia, and over time, having gathered all his strength and fifty armed hussars, he set out for the Polish homeland, also gathering wandering soldiers he met along the way. Russian troops blocked his way at the town of Stanisławów, where another battle ensued, and Benyovszky was taken as prisoner of war by the Russians. He was kept in Kyiv and then in Kazan, from where he escaped, but was later captured again in St. Petersburg.

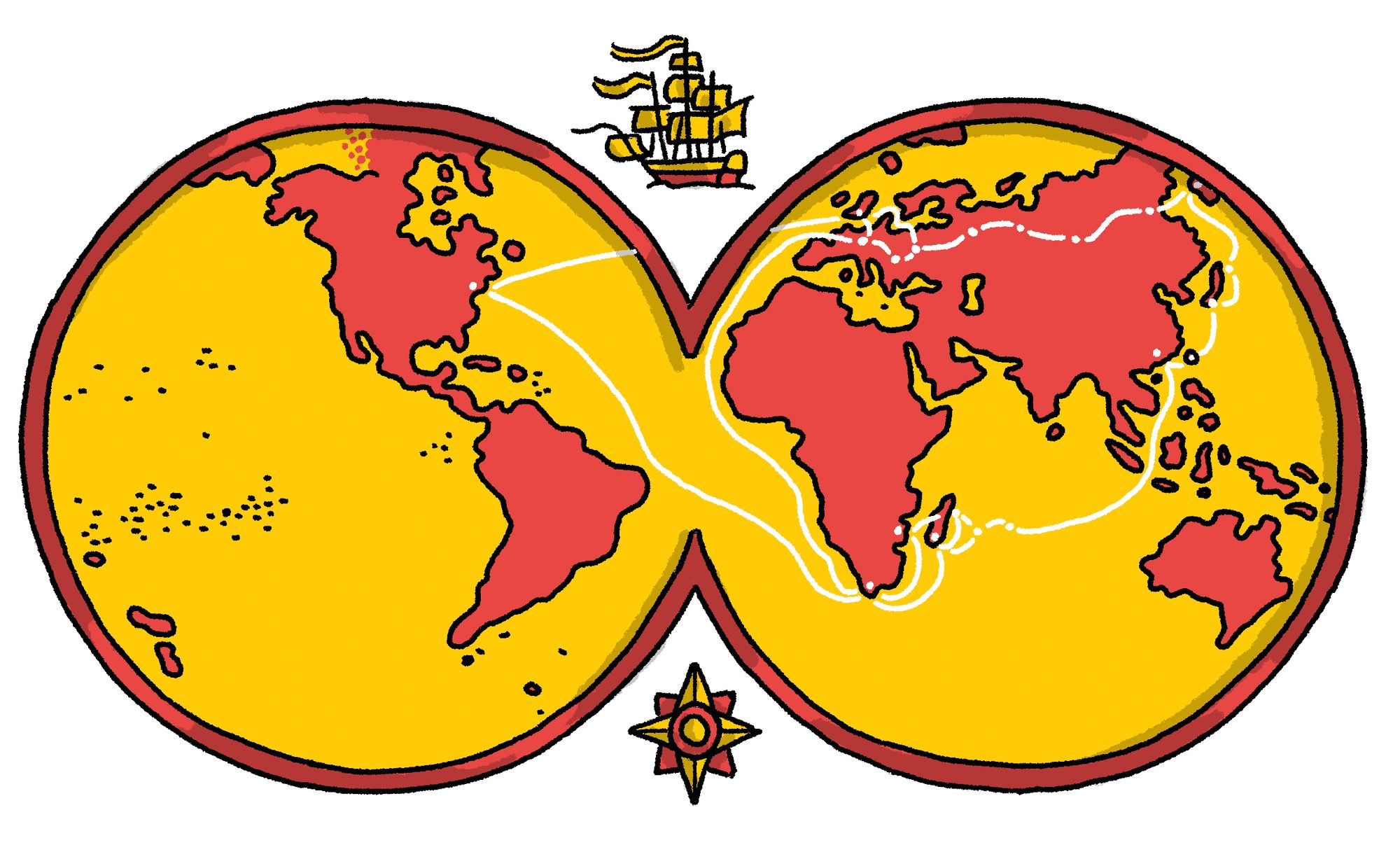

His first great journey began in 1769, as he continued his Russian captivity in Siberia, more precisely in Kamchatka, the farthest corner of the Russian Far East. Already during the Polish fights, Benyovszky had demonstrated that taking a stand for the freedom of the oppressed is a cornerstone of his character, and the cold winters of Kamchatka further tested his strength. During his years spent at the labor camp, he created the first geographical, ethnographic and zoological description of Kamchatka. Yet he did not waste much time, for in the spring of 1771, he organized an uprising with the involvement of tsarist officers exiled to the Bolsheretsk labor camp, occupied the town’s fortress and the ships anchored in its port, and wrote a manifesto. This document became the most revolutionary manifesto in the history of Russia to that date, providing a model for the manifestos of later Russian revolutionary movements.

The insurgents, led by Benyovszky, left the port of Bolsheretsk, and the maritime knowledge acquired in Poland has started to pay off. First, they made their way to the Aleutian Islands, and then briefly touching the Kuril Islands, they landed in the territory of the Republic of Formosa, known today as Taiwan. The last exotic stop on their East Asian trip was Macau in southern China, from where Benyovszky, with a bold stroke, traveled back to Paris.

The time spent in Paris held another great adventure for him, as he founded the settlement of Louisbourg in Madagascar on behalf of the French in 1774—creating the first colony on the previously independent island. The natives of Madagascar elected the worldly nobleman as their “king” in 1776, however, Benyovszky had to resign under French pressure. Meanwhile, the Viennese Court had also appeased, as Maria Theresa, who had earlier exiled Benyovszky for over twenty years, granted him the rank of a Hungarian count in 1778. With the issuing of his patent of nobility, the world traveler returned to his homeland hoping to utilize his knowledge of trading, but in the absence of Hungarian and Austrian supporters, he decided to set off for the New World and then returned to Madagascar in the service of American merchants. The life of Móric Benyovszky, the nobleman of Nyitra County was ended by the governor of Mauritius in 1786 when he fell in a battle fought with the French.

Benyovszky’s character is truly Central-European: freedom-loving, independent, adventurous, and persistent throughout. His heritage makes an integral part of our region’s history. The military man holding the title of a Hungarian count, born in today’s Slovakia, is considered Hungarian in Budapest, Slovak in Bratislava on account of his origin and place of birth, while due to his Polish ancestry and his role in the Polish War of Independence, Warsaw also rightly claims Benyovszky’s historical legacy.

At times, historians and heralds of the three nations would clash over the national identity of a historical figure who lived in an era when identity had three foundations: ruler, religion, and social status.

Our region has a shared history, and due to the largely organic development of Central Europe, it is futile to try to form exclusive rights to the legacy of historical figures of such great stature as Móric Benyovszky.

The nations of Central Europe are so closely knit together that we share each other’s stories, and one nation’s historical memory and heritage belong to all of us. The common historical heritage is not a cake that needs to be sliced and divided, but instead it should be shared with all, setting a positive example. After all, this is how our region can be built from the past to the future: our shared “superheroes” are collective stories.

Often, we imagine ourselves as tiny, bickering nations of the East, torn apart by nationalistic legacies. Would there be Western heroes disputed by the French, the English, or the Americans? Undoubtedly. European migration from Europe to America has raised similar issues in many cases. Perhaps someone studied, completed research and worked in Europe, but then became world-renowned thanks to their activities and results in the United States. Is it possible to separate history from the result? Certainly not. The life of Móric Benyovszky could not have been anything like what we know of, without the history of all three nations of his origin.

Prefer to read it in print? Order the second issue of Hype&Hyper magazine from our online Store!

3h architects competes for the ‘Building of the Year' title