Alfréd Hajós, Alfonzó, Tamás Somló and many other famous Hungarians rest in the Israelite cemetery in Kozma utca, but this is not the only reason why the necropolis in Kőbánya is worth visiting. Our friend and HYPE STORE ambassador Miklós Vincze guided us through the vast graveyard, featuring some quite extraordinary shrines decorated with butterflies, a broken propeller or a car amongst the exquisite mausoleums.

City enthusiast journalist Miklós Vincze wrote about the Israelite cemetery in Kozma utca four years ago: the article of the Ismeretlen Budapest (Unknown Budapest) series, illustrated with rich visual materials revealed many peculiarities and oddities about the story of the graveyard. After the article was published, many people contacted the journalist and asked him to hold a guided tour in the cemetery. And now we joined the latest session of the popular cemetery tour which has been held almost forty times since then.

Even though we weren’t entirely sure whether it was worth going all the way to this part of District X, we weren’t disappointed. We travelled to the final stop of tram 28A from Blaha Lujza tér together with the participants of the walk, to the stop named Új köztemető (New Public Cemetery) – the entrance of the Israelite cemetery is a few minutes walk from here. We would have been better off with tram 28, as it stops right at the entrance of the cemetery.

The cemetery in Kozma utca situated right next to the New Public Cemetery opened in 1886 was established seven years later, in 1893. The Jewish people of the time thought that they needed their own cemetery, just like Christians. Even though there were Jewish cemeteries in the city before, these either disappeared or were transformed, and most of the time, burial grounds for Jews were established in certain confined parts of Christian cemeteries.

The mortuary built in 1891 in Moorish style rises to the sky near the entrance of the cemetery, the central hall of which decorated with a bronze chandelier is still used for funeral services unto this day. The mortuary was designed by Vilmos Freund, who also designed the Sváb Palace on Andrássy út and Duna Palace in Zrínyi utca.

Not too far from the gate of the cemetery, we are already welcomed by one of the most beautiful graves. The crypt of the Brüll family resembles the shape of Ancient Greek churches and stone lions made by Alajos Stróbl are guarding its stairs on both sides. The former legendary leader of MTK, Alfréd Brüll and his family members are buried here – the run-down mausoleum was renovated in 2017, and today it shines in its original glory. The mosaics of Miksa Róth are more glorious than ever before, however, the original wrought-iron gate disappeared over the time.

Jewish architect Béla Lajta – formerly: Leitersdorfer – designed several shrines in the cemetery. In addition to the mausoleum of the Gries family with an entrance decorated with stars and with mosaic on the inside, the Art Nouveau-style, floral sepulcher of the Schmidl family is also worth our attention. The unusual shape of the structure, the bluish-greenish Zsolnay pyrogranite, the gate portraying a weeping willow makes us stop for two minutes, and of course we try to peek through the bars. Three rooflights let the light into the interior of the sepulcher: here we can once again see a Miksa Róth mosaic: the marble board on the back wall is framed by an eosin glaze decoration.

The shrine designed for Jakab Kudelka was completed in 1912: the bird and flower shapes are displayed in a more geometric form, arranged into a structure on the marble block.

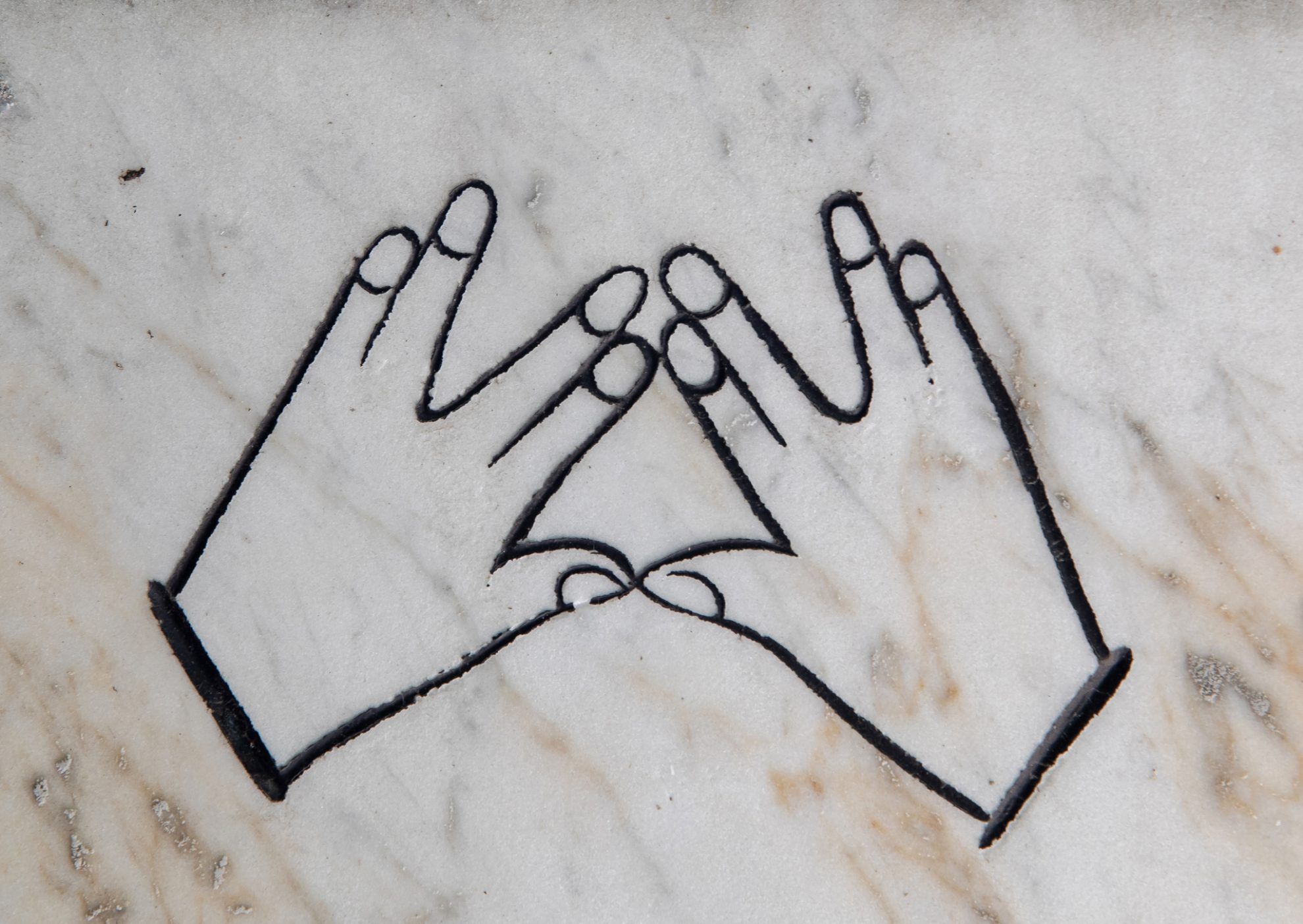

In Budapest, Lajta has also designed Rózsavölgyi house at Szervita tér, the tenement house of the Harsányi brothers located at Népszínház utca 19. and the building of today’s Újszínház (New Theater, formerly: Parisian Cabaret). Lajta himself also lies in this cemetery, his shrine was designed by Lajos Kozma, and no, it is not the symbols of Freemasonry that are displayed on his tomb, but the symbols of architects: triangle, ruler and a pair of compasses.

The almost three-hour travel in time might sound extremely long at first, but obviously we didn’t manage to walk through the entire area of the cemetery even within the three hours. We are not saying that from now on, we’ll think of visiting the cemetery in Kozma utca first when are to decide what to do on a lovely Sunday afternoon, but it’s certain that this milieu requires a completely different state of mind from the otherwise experienced urban walker: due to its sacred nature, this place forces the man of busy everyday life into a relaxed and calm contemplation. Ultimately this is also a city, the city of the dead, where you can get lost and marvel at beautiful, special and exciting details just as much as in a regular one.

The shared shrine of Henrik Ohrenstein and Sámuel Rendlich leading a construction company in the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy was designed by Ignác Alpár. The mausoleum resembling the shape of Ancient Greek churches and made of black granite has withstood the test and trials of the past more than 110 years majestically. The following quote reads on the inner wall of the church: “Who loved and cherished each other in life, will not part after death either.”

While walking in the cemetery, we see an odd symbol everywhere: a hand signal, which may be familiar for Star Trek fans. In the TV series, this hand position equals the “Vulcan salute”, however, it can be traced back to the Kohen (the nation of Jews considering themselves of direct patrilineal descent from the biblical Aaron). This motion is a blessing of priests: the position of the fingers resembles the letter Shin, standing for “El Shaddai”, meaning: “Almighty God”. Leonard Nimoy, the actor playing the part of Mr. Spock saw this sign in his childhood, when his grandfather took him to the synagogue.

As opposed to Christian cemeteries, Jewish graveyards almost never feature human portrayals, yet there are some exceptions in the cemetery in Kozma utca. For instance, we see the statue of a gigantic female figure at one of the tombs – the descendants must have taken it over from the villa of the owners. Laurel wreaths, broken wheels, gun barrels, lions, swords and helmets can be seen on many tombs which belong to heroes and soldiers.

We also see a butterfly on one of the tombs in the children’s parcel – Miklós, who has been returning to the graveyard for years, tells us that these children tombs are maintained by elderly women, who “adopt” shrines on a voluntary basis.

We also find two car-related tombs in the cemetery in Kozma utca: one decorates the shrine of László Hartman, a Hungarian racecar driver from the 1930s, and other is the car of Adler Terus Kunstadter Vilmosné, who got the vehicle from his beloved husband (after her death). We can see a broken propeller on the tomb of Viktor Wittmann frequently referred to as the pioneer of Hungarian aviation, who died at a young age in a plane crash.

The deceased lying in the cemetery at Váci út (formerly known as the Jewish cemetery at Aréna út) were reburied in the cemetery in Kozma utca, amongst others, after its elimination in 1910. This is demonstrated by the white marble tombstone decorated with a roaring lion and floral motifs, commemorating the exhumed heroes of the 1848–49 Revolution and War of Independence.

Alfréd Hajós rests here, too, and he also has another connection with the cemetery. The Olympic swimming champion and architect born under the name Arnold Guttmann designed the memorial built for the victims of the Holocaust in 1949, displaying hundreds of thousands of names (there even ones written with pencils). There is a sign on the granite block rising before the giant stone wall: “They were killed by hate – let them be remembered by love.”

The next tour will be held this Sunday, on August 9. You can find the details of the event on the Facebook page of Ismeretlen Budapest.

Creating freely without boundaries | Classmate Studio