There are some dishes that are familiar to all of us. Flavors feeling like home preserved in cans or drops thought to have medicinal properties, wrapped into crinkly, rattling paper—this is what we set out to explore each month in our freshly launched ‘Büfé’ series. The first chapter is about our favorite herbal lozenges.

Written by Bianka Geiger

Májkrém, krumplicukor, téli fagyi (liver pâté, potato candy, winter ice cream)—meals and snacks that several generations of Hungarians stored in their cupboards, bags and pockets. No matter whether the memories they bring back are good or bad, these products still give rise to a feeling of nostalgia in all of us. Many of them have disappeared but are now experiencing a renaissance and we thought they deserved some appreciation. In our series launching this January, each month we’ll explore another iconic food for a year. Welcome to Büfé!

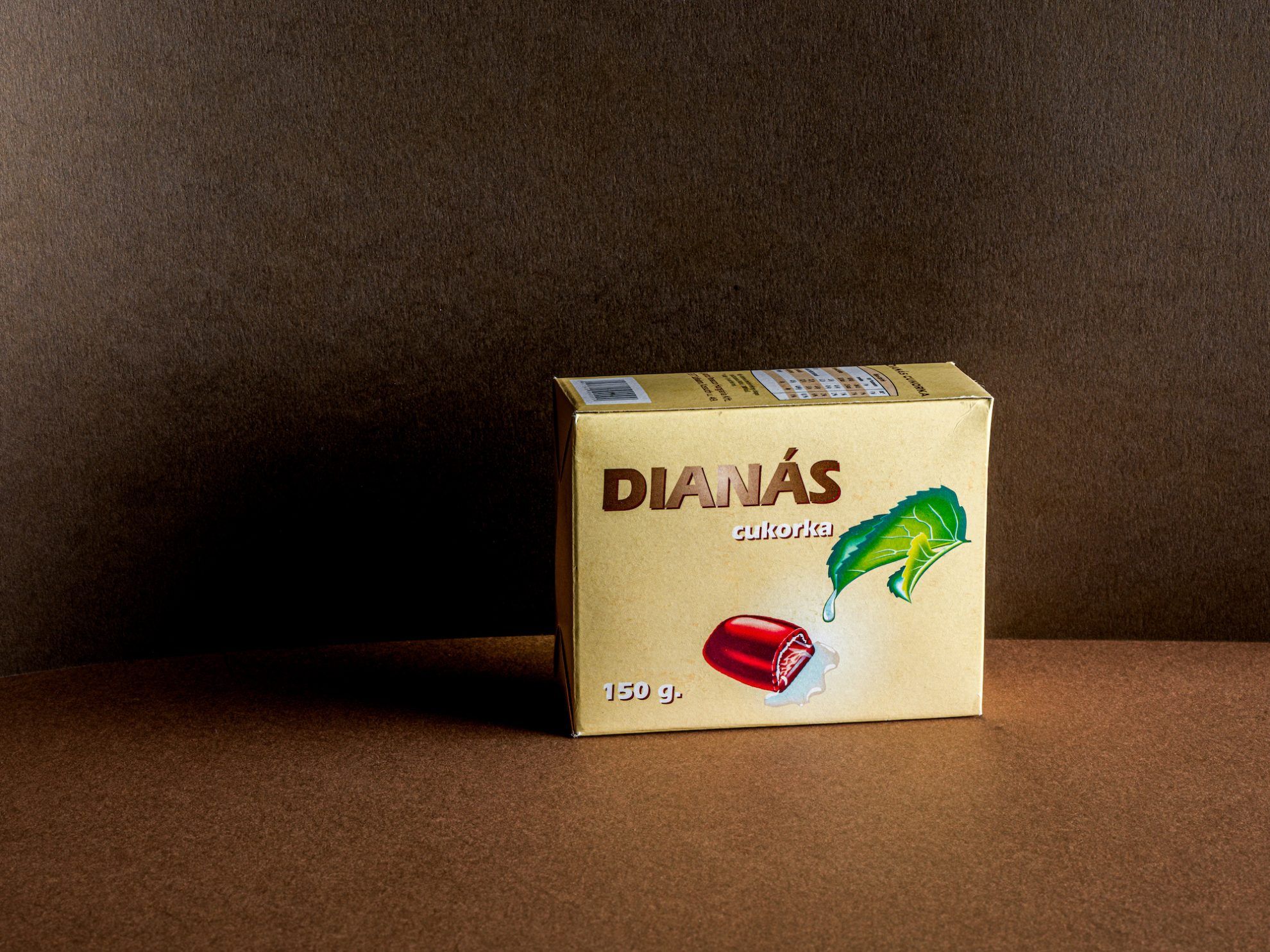

When I was a kid, my mom used to tell me a lot about krumplicukor and she was always very happy to taste it whenever she found some. To be honest, I never really understood her infatuation—this version of potato starch pressed into bars always reminded me more of chalk than a sweet treat. At the same time, my grandma always had some sweets in the pocket of her apron and from time to time she’d give me some. It was either Negro or Dianás cukor—I especially liked the latter, even though I know it is a polarizing treat: people either love it or hate it, there’s no in-between. Then Dianás was gone for quite a few years, but it has once again been available in stores for a while: and even though the market of “healing lozenges” have expanded since, the great will always have a place in it.

All Hungarians know that the main ingredient of this iconic candy is „sósborszesz” (rubbing alcohol). Let’s see where this ingredient comes from! The story goes like this: pharmacist Béla Erényi placed the mentholated rubbing alcohol on the market in 1907—he was trying to defeat his competitor Kálmán Brázay, who dissolved various herbs in alcohol which he diluted with salty water and sold as medicine for both internal and external use. Sósborszesz or rubbing alcohol is exactly what its name suggests: water, alcohol, salt, ethyl-acetate and menthol. They used it for everything from treating pain to rheumatic complaints to sanitization, but it was Erényi who made it great finally. He launched a marketing campaign under the aegis of Diana that has carved the name in stone. The shape of the candy was born a few years later when they realized that when molded, the solution crystallized while cooling down and thus they didn’t have to pour the liquid into a crust because the material itself formed its crust on its own. Then the product was dipped in chocolate and finally packaged into silk paper, each piece hand-wrapped.

But Dianás was not the only lozenge that became popular in Hungary over time. The white horehound candy born in 1884 was perhaps even more divisive, credited to pharmacist Béla Réthy. The inimitable greenish-grey color and scent of the drop containing white horehound, chamomile, plantain, tilia cordata and woodroof haven’t changed a bit ever since—the demand didn’t diminish during the world wars either, but Réthy’s company could not avoid nationalization, even though he never handed over the exact recipe. Then in the nineties, János Rezsu, the executive director of Érd-based company Microse Kft. contacted the former employees still alive at the time and gave a new life to the brand with their help: thus the drop is now available in several versions all preserving the traditional flavors, both in the iconic metal container and paper packaging.

The current flagship of throat lozenges is Negro, of course. The almost 100-year old brand started out in Kőbánya, next to the beer factory—legend says an Italian worker, Pietro Negro came up with its recipe almost accidentally using the side products of hard candy production. The exclusivity is debated, as another Negro brand was also born in Serbia in the early 20th century, which unveiled similar products as the Hungarian label. The traditional black version created unforgettable flavors with its anti-inflammatory and cough suppressant liqourice-anise-menthol ingredient trio, and dominated the Hungarian market until the nineties—it was the go-to lozenge of famous Hungarian actress and singer Katalin Karády, too. Then came the upgrading with honey, eucalypt oil and red berries. The black Negro became a cultural symbol—countless expressions and anecdotes are associated with it, not to mention the chimney sweeper figure or the advertising campaigns.

Of course there are other similar “medicinal sweets”, too, in the region. In Slovakia, Hašlerky is the preferred choice—the original Viennese recipe of the candy was brought to Prague by a businessman named František Lhotský in 1917. The traditional name given after the Italian opera singer Caruso was not Czech enough, thus he convinced a famous local artist, Karel Hašler to give his name to the product. Hašler gave in, and so the famous slogan was born: „Hašler kašle, nevadí, hašlerky ho uzdraví.” meaning „If Hašler coughs, no worries, hašlerky will come to help.” The product was a roaring success, and it is still made according to the original recipe near the Slovakian border today, now under the aegis of Nestlé—also expanding the palette with new flavor variants.

What all these candies have in common is that they are, as a matter of fact, sweets, but with the local use of herbs they promise a beneficial impact on our health and so we grab them from the shelves of stores without any guilt. Except for tiny changes, the shape, color, taste, scent and packaging of these candies still follow the original design, but somehow they don’t even need upgrades—they become contemporary exactly by evoking the times that seem peaceful and carefree today and by remaining relevant and lovable to this day.

Sustainable plant growth through a dreamy light installation

„We complement each other in our work” | Peltan-Brosz Studio