Although we’ve already introduced you to the magical world of Chinatown and the Indian community in the previous episodes, Asia has so much more to offer. Moving beyond the sushi counters of the shopping malls, if you roam the streets of Budapest with a conscious mind, you can meet some truly lovely people who have created a new home away from home, through food. As they say, bon appétit, or itadakimasu!

When we think of Japan, very often clichés come to mind. While I like to think of myself as a more informed foodie than the average, I admit that even a few weeks ago I would have struggled to name five specifically Japanese dishes or eating habits that weren’t Korean or Chinese. Perhaps that’s excusable, as the island nation dwarfs China (by comparison, the former is home to 125 million people, the latter to nearly (!) 1.5 billion), and their culture (and therefore their cuisine) is very diverse, depending on the region you are in. The first inspiration that sparked my curiosity about the Japanese living in Hungary came from the Japanese ambassador, Otaka Masato—specifically by the amazingly colorful, exciting and playful bento boxes he regularly posts on his Facebook page, as well as his series of posts about the local restaurants. I wondered: how many Japanese people live in Hungary, when and why did they arrive and how do they live their daily lives here?

According to my sources, the community here is about 1500-2000 people, and a significant number of them are students or diplomats staying for a short period of 3-4 years. In 1991, the Hungarian Suzuki factory opened, which gave a big boost to migration, but the process was slow. In 2020, there were nearly 200 companies with branches in the country. The newcomers in this sector are typically middle managers/executives who move in their own circles but are also very open to Hungarians and Hungarian culture. Incidentally, the two countries first established diplomatic relations during the Austro-Hungarian Empire in 1869. Japan has supported the development of the Hungarian economy to a great extent during the restructuring of the country during the regime change, which has led to particularly good relations, not to mention the fact that the Japanese also like to visit Hungary as tourists. In addition, the world of Japan is also very popular among Hungarians, such as Japanese gardens, martial arts, cherry tree blossom and the House of Hungarian Music designed by Sou Fujimoto.

Many people helped me to learn about the community. One was Maki Stevenson, whose name may ring a bell in gastro circles. He is the founder of Makifood and the Culinary Institute of Europe. Food has always played a very important role in Maki’s life. Her mother learned to cook as a married woman, and her second husband was an American, who influenced her to become very knowledgeable about American gastronomy. She held Japanese cooking classes for Americans and American cooking classes for Japanese, and Maki grew up in this environment. As an adult, she followed a vegetarian diet and became self-taught in cooking. She met her husband during university (by the way, she was studying to be a cellist) and in 1997 she visited Hungary for the first time, then they moved to New York. While she was studying gastronomy (she graduated from the Natural Gourmet Institute for Health and Culinary Arts, where she learned not only about food, but also about its health and social impact), she was given the opportunity to work on European projects—at first, Amsterdam seemed to be the new base, but they ended up in Budapest. Missing European culture, they returned home with joyful anticipation and big plans. At first, she wanted to work as a private chef, but there was no market for that at the time. Then she wanted to rent a kitchen for catering and started cooking for friends in a tiny 8-square-meter kitchen, delivering healthy food to his house on an old bicycle for as long as he could (getting up the Rózsadomb was a challenge). More and more people asked for recipes, so she launched cooking classes and the good word spread… And so, Makifood was born. With this, her aim was to connect people and show the similarities between different cultures.

In 2016, seeing the gap in the Hungarian gastronomy education, she founded CIE. The plans had been in the pipeline for a long time, all they needed was a partner, who turned up relatively quickly. The aim was to give students real-life experience, therefore she invited real chefs to teach and contacted several restaurants in order to organize internships. The new headquarters on Bródy Sándor Street now offers an expanded portfolio, with Eat Art, a Pastry Arts and a Plant-Based Program. Encouraging teamwork from the start, there are no separate workstations, everything is shared. This is how real challenges and real responses can emerge. These revolutionary methods finally offer an alternative to the somewhat dusty, home-grown approach to gastronomy education, so you can learn from the best in a specialized way and prepare for professional challenges.

He was also the one who helped me to get my bearings in the mysteries of Japanese cuisine. Its main characteristics are simplicity, purity and harmony: the aim is not to overdo anything or to be too garish, but instead to let the nature of the ingredients prevail. This is perhaps most visible in the countryside—in this, they are similar to Hungarians. Both cultures have a strong respect for tradition and try to integrate it into the food of the present. Of course, as in all cultures, reality is not all romantic. The Japanese are famous for their almost insufferable work ethic, stressful daily lives and quick, cheap snacks on the go. While it would be nice to think that there is always time for a long meal, most people eat on the go, often sitting/standing at street stalls, even in suits.

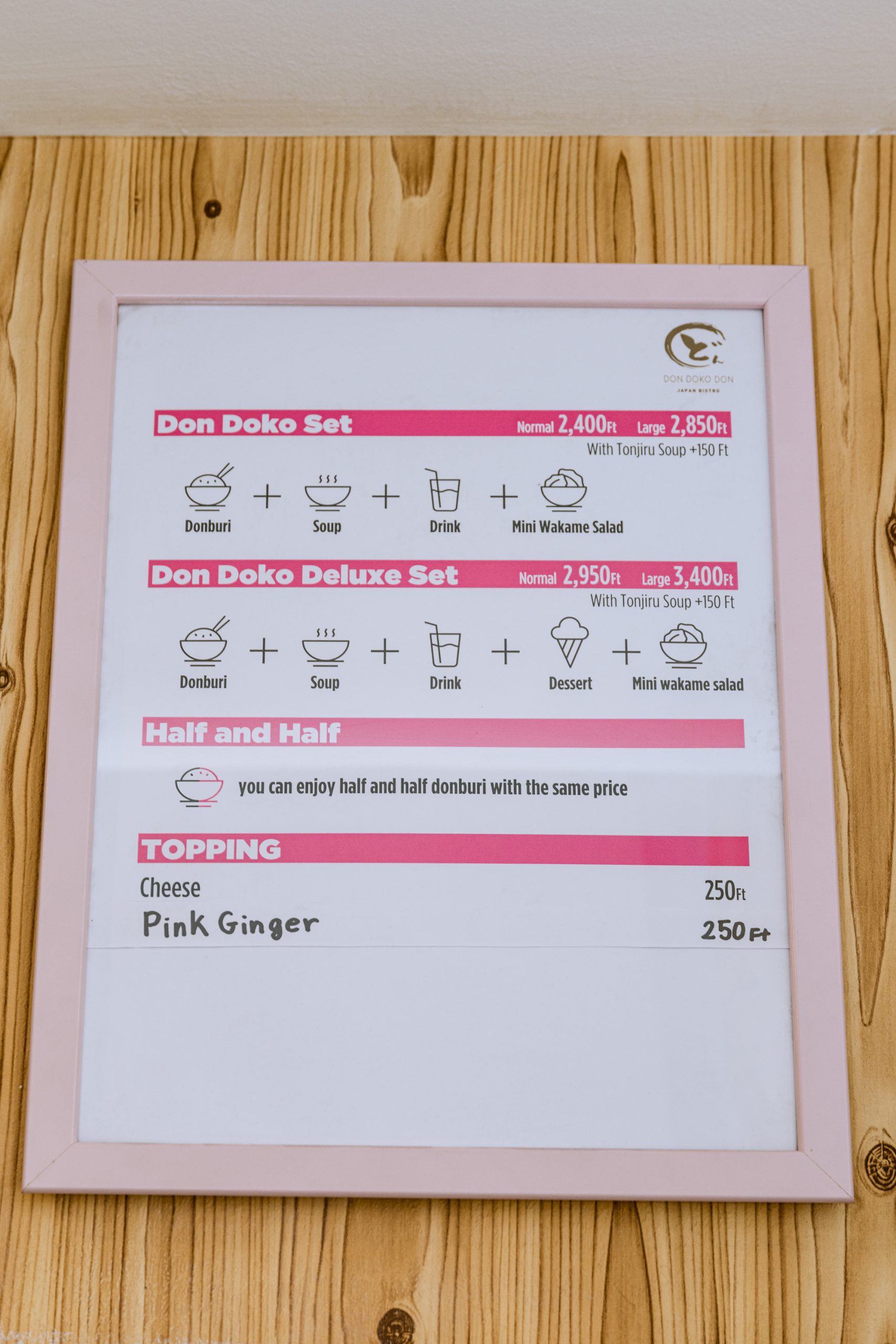

Perhaps the key difference is that even street food is much healthier than in Hungary. Their base is rice, topped with fried meat or tofu, vegetables and some kind of sauce, in various forms. One such dish is donburi, which can be prepared in many different ways and is very popular in the island country, but is not known in Europe. The word comes from the Japanese word for ‘bowl’ and was popularized in the Edo period (1603-1867). Watanane Tomoki, the founder of DON DOKO DON, saw an opportunity in this when he opened his restaurant next to Kálvin Square in 2019, following his wife’s arrival. The quick-to-prepare, filling and delicious dish has instantly become popular with students and workers in the area, foreigners and Hungarians alike, as it brings familiar flavors. Pork or beef, vegetables, rice and sauce—the latter is simple but great, made with Hungarian white wine instead of sake, and the result can be taken anywhere in a box.

And when it comes to filling dishes, the iconic Japanese ramen and curry should also be mentioned. Although every place has its measure, generally speaking, ramen is made from long-cooked chicken, pork or beef stock, with wheat flour homemade noodles, pak choi and possibly eggs, corn, seaweed, bamboo shoots, an endless variety of toppings. The broth can be made with salt (shio), soy sauce (shōyu), miso paste, tonkatsu (meat) or curry. Compared to Vietnamese phở, it is generally a fuller, darker soup with more pronounced flavors, but like phở, it can be varied in many ways. Curry also differs from its Indian cousin in that it does not include pulses or dairy products, but is based on a spicy sauce of potatoes and carrots, blended creamy and thickened with starch, and served with an omelet, katsu or karaage, or even fried fish and rice.

If you want to try them all, luckily you can taste them at Biwako Ramen House or Komachi Bistro. The founder of the latter, Yoshiharu Mineta, came to Budapest in 1999 and ran hostels for many years. Seeing a gap in the market, he opened his restaurant 8 years ago. His aim was to showcase Tokyo-style food: it’s saltier, but the salt doesn’t mask the real flavors—everything is made in the kitchen, by hand, from ramen noodles to dashi. This may give them more work to do, but he believes it’s necessary for perfect, unquestionable quality and freshness (for which, fortunately, he can find plenty of ingredients here at home). And the flavors are truly great, and the team exudes a sense of togetherness: the owner stressed that he sees his staff as family, so even in the Covid period’s most difficult moments, his priority was to keep everyone. The clientele is very mixed, but it shows that there is something for everyone.

This relaxed attitude is also typical of the izakayas. An izakaya is a kind of Japanese pub or gastropub (the Konyhakör team has opened a similar restaurant, Ensō) where people gather after work to drink, chat and nibble on a variety of snacks. The food here is more varied, or even more substantial than you might think: karaage, for example, is a popular dish and exactly what it looks like: fried meat served with rice and various spicy dressings. Wafu is an energetic spot on the already vibrant Kazinczy Street. The owner, Takashi Nagatake, is a true globetrotter: in search of his life’s ambition, he worked in a grill restaurant in Japan, then took a deep breath and moved first to Toronto, Canada, for a few years, before spending more time in Australia.

He has constantly educated himself, pushed his boundaries and, because his parents own a travel agency, has seen the whole planet. Thanks to an unexpected opportunity, he moved to Hungary two years ago, where he opened Wafu in 2019. Then came the pandemic, and he needed a plan B: while fine-tuning and testing food, he made bento boxes for hospital workers, for example. The Osaka style was already emerging: richer flavors, more dashi, bolder combinations. In the meantime, he made more and more friends in the local culinary scene, which led to several collaborations, one of which will hopefully soon result in a new restaurant.

Another izakaya also operated for a while, called Kicsi Japán Izakaya, but unfortunately, it closed during the pandemic. Even though its founder is well known, in fact, as a master of sushi. A bit of background: when I ask around about the best places in Budapest for something, I very rarely get a consistent answer. The title of best sushi maker, however, seems to have been won by someone—Hirose Yoshihito is here from Osaka to show us the noble simplicity of the world of sushi and sashimi. The chef used to have a restaurant in Japan, too, but a Hungarian guest invited him to our country. Almost unnoticed, he opened Kicsi Japán in 2019 in a tiny shop under the arcades of the Corvin Quarter. Here he prepares the food in front of his guests, in perfect harmony with his assistants.

For half an hour, we watched in silence his ceremonial, perfectly tuned, practiced movements and the devotion he gives to his food. Every detail, as he explained, is given special care because he knows that the dish will be perfect if the cook puts his heart and soul into it. From the marinade on the rice to the nine kinds of incredibly fresh fish to the serving, every step has its own order. Next to the shop, he has also opened a small grocery store where you can buy a variety of Japanese ingredients. Half of the guests are Hungarian, the other half are either Japanese residents or tourists, so he sees that they understand and appreciate the hard work. If someone would prefer to abstain from fresh fish, they can choose from grilled versions with cheese, or roast beef, foie gras, or various rice-based dishes. But my main recommendation is that if you can, sit down and take the time to experience the magic of food preparation.

And what can you do if you just want to have a bite to eat or refresh yourself? You can drink a traditional matcha tea, or try fruit sando, which artfully presents whipped cream and fresh fruit, or a mochi made from rice flour and filled with red bean paste or something else. If you don’t have a sweet tooth, okonomiyaki is a good idea: it’s a nationally popular dish born from the meeting of pancakes and omelet. (Eggs are popular on their own, too, with omurice, for example, an egg dish served with rice, in the latest trend for exciting tornado-shaped dishes.)

Even its preparation is a choreography: thinly sliced cabbage is topped with pasta, followed by soybean sprouts, onions, pork or fish and pasta. When the ingredients are well browned, the chef adds the egg to the hot plate and fries the whole thing—this is the Hiroshima layered version. The dish is topped with sweet and smoky okonomiyaki sauce and mayonnaise, possibly topped with bonito flakes, but there are many other enriching ingredients, such as thinly sliced yams. There are several styles, such as that of Kansai, where everything is mixed together and the layers disappear, but it can also be made with buckwheat noodles. At Okonomiyaki Tatsu, you can try a variety—the chef and owner, Wu Bingchen Tatsu, is Chinese but became a fan of the food thanks to the original Japanese owner of the place. It’s a privilege to watch him prepare the food, including a vegetarian version on request. With a menu change and a new look coming soon, it’s definitely worth a visit, but in the meantime, here’s a pro tip: when buying Japanese products anywhere, look at the barcode—you’re on the right track if the number starts with 47.

Another contributor to this article was Zília Tóth, a staff member at the Embassy of Japan. Zília spent much of her childhood in Japan, so she picked up the language quickly. She later worked as a freelance translator and yoga instructor for many years but had to plan again during the epidemic. She now works as a member of the embassy team and is also a committed advocate of a vegan lifestyle together with her partner, furniture designer László Bergovecz, who is also president of MAVEG. Also, for her, Japan is a place of honesty and purity, so she happily accepted my invitation and I thank her very much.

Photos: Krisztina Szalay

Previous episodes of the series:

The (neon) imprints of Budapest's history in Isabel Val's photographs