Modern cities are unthinkable without the presence of parks: places, maybe even more, refuges reserved for nature, meant to be organically embedded into the urban tissue for the leisure and pleasure of all city-dwellers, serving as an experience of freedom always within reach.

The coexistence of city and nature has a complicated history, starting from the very foundation of the first cities about 5000 years ago. In particular, parks, i.e., intraurban nature reserves have been slowly transforming from royal hunting areas into places of citizen activity, in parallel to the advent of the industrial city and, thus, of new social phenomena such as the free time of workers.

Author: Kulcsár Géza

Thus, a park as we know it is a relatively recent and typically modern phenomenon. This is especially true for Budapest. While the historical section of the city, Buda, is naturally set on hills on the right side of the Danube, and, thus, has a trivial connection to nature (it is enough to think of the Gellért hill, which, of course, has been consciously shaped as a recreation space, but still conveys a genuine feel of being in the nature), it is rather in those areas of Pest and southern Buda where industrial urbanization occurred as a controlled tendency. It is in these parts of the city that we can talk about conventional park creation as a dedicated activity.

It strikes us very soon that the history of the parks of Budapest also tells us about the different stages of the development of the city as a whole. In such a short piece, we cannot enumerate all the parks and gardens of Budapest, not even the major ones and not even superficially. We instead aim at highlighting some paradigmatic examples and historical milestones, with the underlying intention of inspiring the reader to discover these and many more!

During the gradual emergence of modern urban planning throughout the 19th century, it was not always absolutely clear if green areas belonged to the idea of a city or if they should be incorporated into the city tissue. Indeed, the first public gardens of the city, Városmajor (approx. ‘city farm’, as the site was a former hayfield) in Buda and Orczy-kert (‘Orczy park’, however, kert rather means garden) in Pest, arguably predate the conscious, disciplined shaping of the urban tissue (note that we are still before the unification of 1873). In the Városmajor, the planting of trees started as early as 1787, and it always remained a culture and leisure hub of Buda, also hosting an iconic modernist church. After László Orczy opened his then-fashionable sentimental garden to the public in the early 19th century, it underwent an elongated period of gradual decline, however, since 2012, the fully renewed Orczy-kert shines in its old glory.

Around this time, the Városliget (‘City Park’) was just about to emerge as a cultivated area on the outskirts of Pest. As József nádor (Archduke Joseph, Palatine of Hungary—and a professional gardener!) was convinced that “trees do not belong in the city”, he strongly supported the development of a modern park on the site along with the also world-famous Margitsziget (‘Margaret Island’), both still lying outside of the city proper. The Városliget became a masterpiece of 19th-century garden architecture and one of the first truly public and citizen-centric parks of the world – offering something to every citizen regardless of their class and stance, while also being easily reachable and accessible, according to the wish of its creators. And these days, it is truer than ever! The ongoing Liget project, the most ambitious urban park renewal in Europe, stays true to the tradition of the Városliget, while turning it into a real 21st-century culture and recreation hub, becoming the site of state-of-the-art landscape architecture solutions as well as brand new contemporary architectural masterpieces, housing museums and cultural institutions.

While the Városliget has gradually lost some of its original parts as a consequence of 19th-century urbanization and industrialization, the same changes caused another peripheral development project (commencing in 1868) to become the largest park of the city by 1942. The Népliget (‘People’s Park’), in the 10th district (Kőbánya) of Budapest, continued to grow in relevance after World War II, becoming a showcase project of the Socialist regime – probably also due to being set in the middle of what became an area mostly inhabited by industrial workers. Once the site of numerous attractions and cultural institutions, all that remains is the timeless charm of this huge, yet often almost forgotten urban forest.

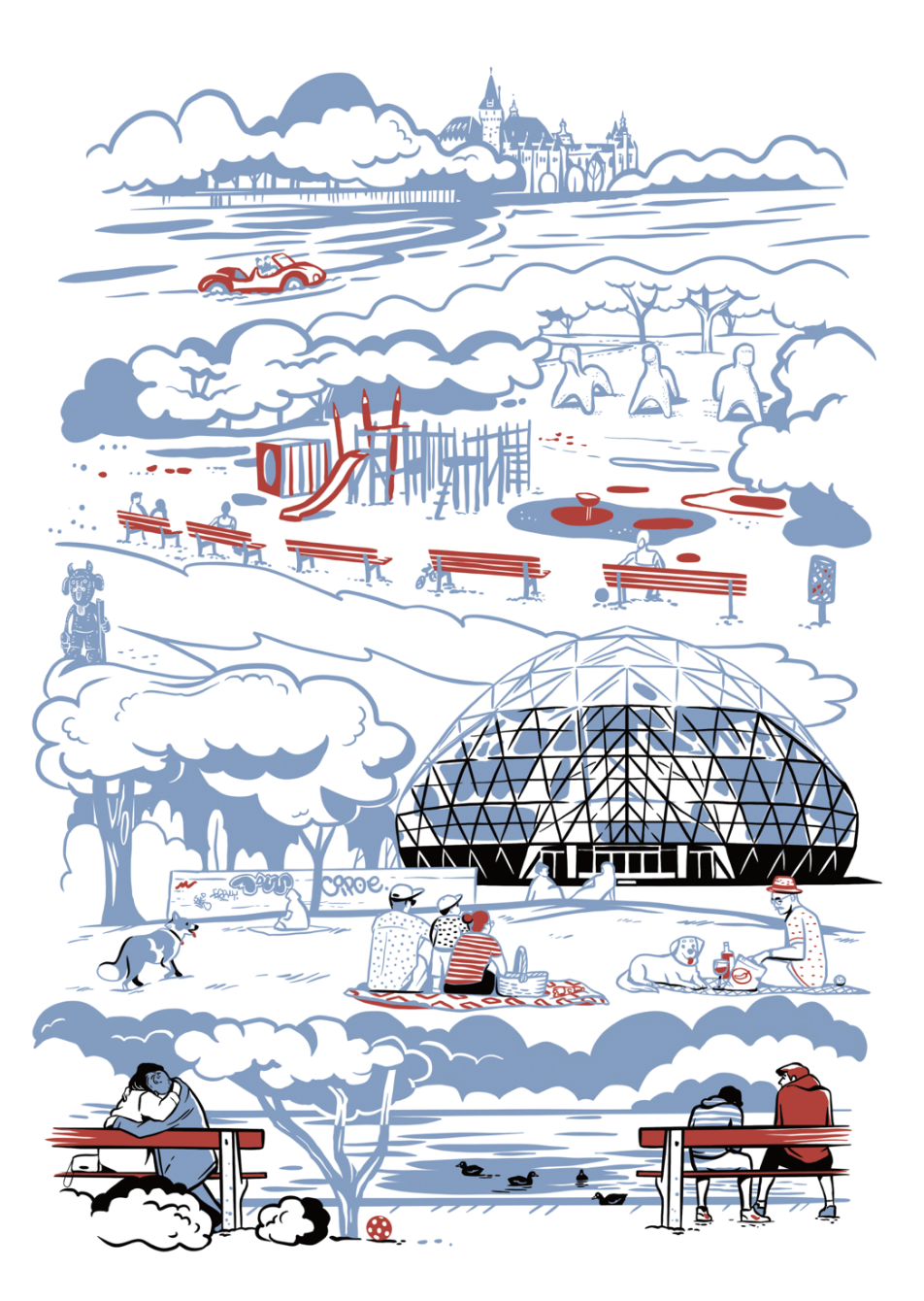

Even more recently, the 11th district of Budapest (Újbuda, ‘New Buda,’ south of the castle and the Gellért hill) has been in the focus of cultural and social changes. The leisure time of the area arguably revolves around a very popular recreation ground, the Bikás (‘Bull’) Park. The namesakes of the park (a statue of three bulls set on a small hill) and the whole area with the surrounding Socialist-era housing (one of the most dense and most iconic among such habitations in Budapest) evokes the spirit of an imperfect, yet timelessly touching Socialist utopia. Now filled with all that we expect from a contemporary park (cafés, sport facilities), the ‘Bikás’ unconsciously and unwantedly becomes a symbol of historical and societal changes.

All in all, parks and gardens in Budapest are as dizzyingly rich and diverse as the city as a whole. It is impossible to do justice to all the fabulous green areas of the city, being so different in their size, layout and atmosphere, in a single piece of writing. Indeed, everyone in Budapest has their favorite city garden, be it a world-famous garden or a small green spot only frequented by a few neighbors. And such a spot will always be within reach. Therefore, the best advice we can give to the reader: go out and discover where your green heart belongs in Budapest!

Best of Stefan Lengyel 2022 | MOME—Institute of Architecture

Highlights of Hungary award winners