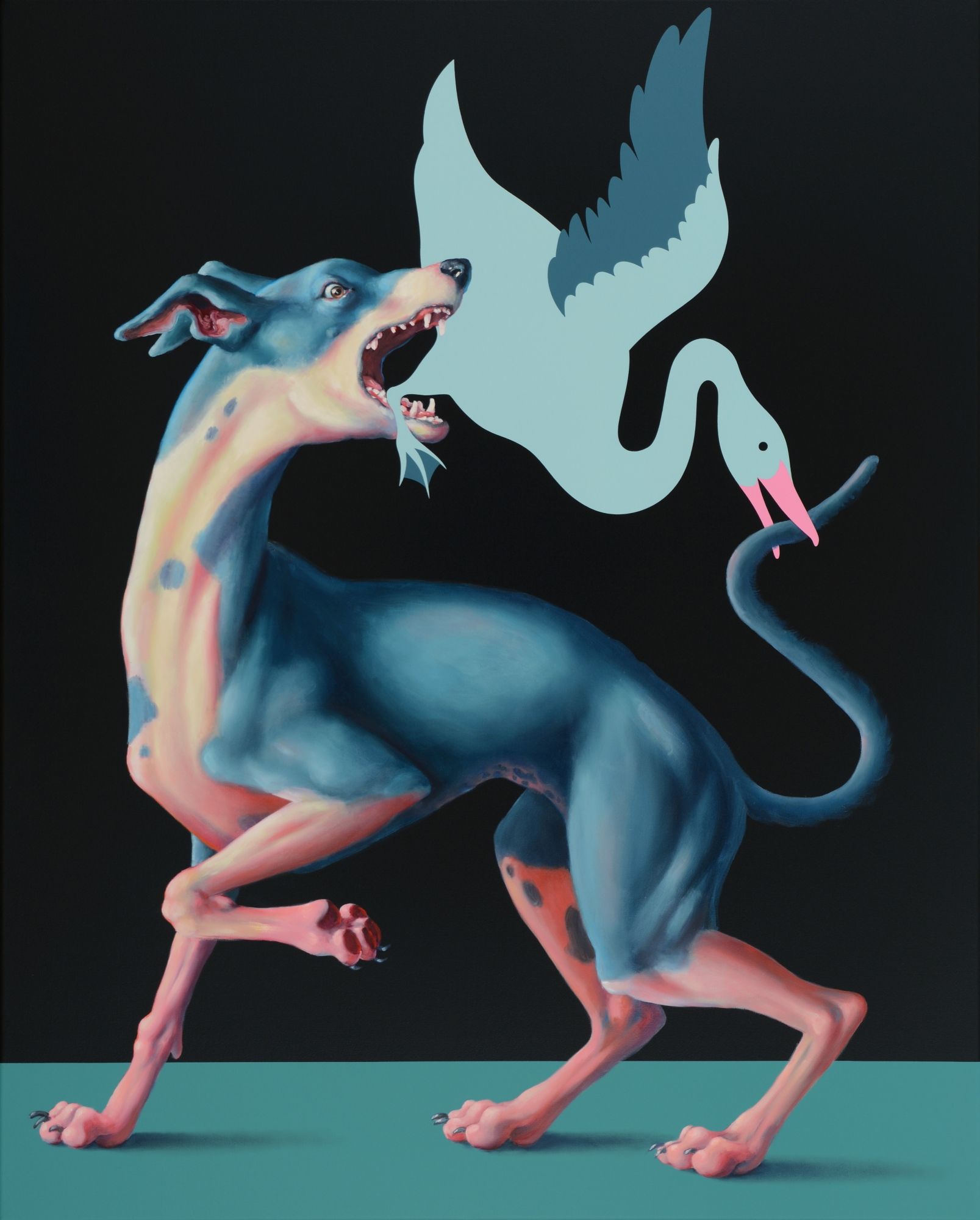

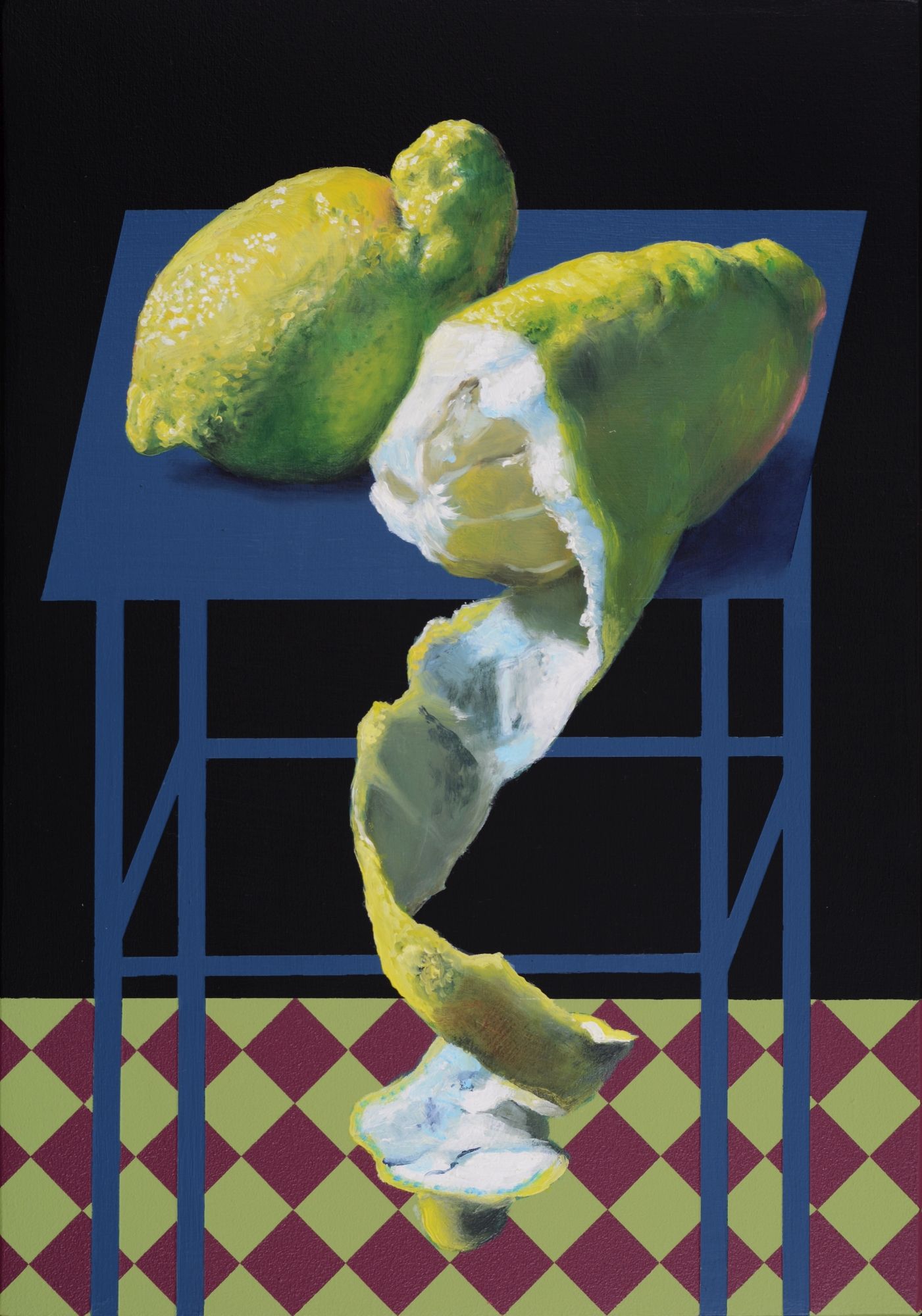

Once you’ve seen them, it’s hard to get his images out of your head. Sensitive still lifes and extraordinary animal portraits with a metaphysical edge. We are introducing the captivating visual world of Máté Orr!

Your exhibitions sell out at record speed, with collectors from home and abroad queuing up to buy your work. How does this success affect you?

It makes me happy! I think every form of art is communication. The fact that many people find my works so exciting that they want to see them every day in their living space indicates that I am succeeding in accurately capturing something about the subjects I am working with.

It’s a privilege I can spend eight hours a day painting, not having to share my time. I’m grateful for it because I extremely enjoy the process of image-making.

Painters’ lives have changed a lot over the centuries. Think of the mature Renaissance portraiture or the still lifes of the German Low Countries, all commissioned by the aristocracy and providing a secure living for the artists. How do you see the situation of a painter in the twenty-first century from this point of view?

It’s absolutely true that art history’s great works were, almost without exception, created in the economic centers of the period. We can paint and go to exhibitions only when we are not hungry or freezing. I think it’s a privileged position to have the capacity to do these things. What is very different today from any previous era is that you can look at anyone’s work from anywhere in the world. Moreover, paintings can be reproduced on a monitor quite well compared to, say, an installation. I follow a painter based in Vancouver who has never had an exhibition in Europe, let alone in Hungary. Twenty years ago there just wouldn’t have been any forum where I could have seen his pictures. I think this is the reason why non-local supportive communities can develop around an artist and why painting has become less economically, conceptually and aesthetically centralized.

You are a member of the permanent artistic circle of Várfok Gallery, one of the oldest private galleries in Hungary. The relationship between a painter and a gallerist is in many ways like marriage. What do you think about this? How do you experience this relationship?

When we look at an exhibition, we don’t necessarily think of it as a work of a large team. Usually, we focus on the artist, but there are many other vital components to a good exhibition besides the artwork. From basic things such as whether the exhibition space is suitable to show the paintings, whether there is always someone there who knows the works, to what events we organize and the way we communicate them to the audience. This is a great, great deal of work, and it gives me confidence to have a gallery with so much experience handling my work.

Despite your young age, you have created a very distinctive and unique painting style and visual world, which has already emerged during your university years. How natural or conscious was it to build your visual toolbox and find your artistic voice?

I didn’t put it into words like that at the time, but I have been interested in subtle emotional reactions between people from my teenage years and it took me over ten years to develop the tools to capture this effectively. This process was by no means self-evident. In the meantime, I studied graphic design, printmaking, anatomy, psychology of art, I also tried my hand at photography, so I was exposed to a wide range of approaches and I was able to try out a large variety of visual tools. Naturally, I saw a lot of pictures along the way. In fact, it was the back of the Wilton diptych in the National Gallery, showing a deer in chains, that really helped me to develop the visual world I have now. It somehow helped to put all the previous experiences in place, but it’s not a finished process. It may not be evident at first, but I’m always experimenting with new materials and techniques, and keep what is good. I used airbrushed dots several times in my paintings this year, which is completely new, but I think it worked really well with the mix of realistic and completely flat details.

Your works are very complex and multifaceted, not only on a visual but also on a narrative level. Where do you draw inspiration from for each painting, and how important is it for you that your pictures can quite literally tell a story?

It is a basic human thing to think in narratives. We live our own lives as stories: we see every new experience as a continuation of the web of our memories. Although a painting can only depict one scene, we inevitably try to interpret that scene as part of a larger story. In this way, I believe that every figurative representation refers to a larger story.

Usually my paintings are about emotional situations that are familiar to us all. I try to create an experience that makes us want to think about these situations even if they are difficult or unpleasant. It has long been a reliable tool for mankind to tell a story by anthropomorphized animals, plants or even objects.

Your painting “Bruant Ortolán” is looking back from the cover of contemporary poet Márton Simon’s latest book of poems (Márton Simon: Éjszaka a konyhában veled akartam beszélgetni, Jelenkor, 2021). How does it feel to see your work in an applied art context?

When we talk about contemporary art or contemporary poetry, many of us tend to think of something hard to grasp, not relating to the quotidian, too serious. What we have in common with Márton Simon is that we both deal with personal events that are relatable to everyone. I am thrilled if the picture, stepping beyond the world of exhibitions as a book cover, can contribute to bringing contemporary art closer to us and to making it feel even more an integral part of our lives!

Schrödinger’s Jaguar by Máté Orr is on display at the Várfok Gallery until November 6.

Photos: Máté Orr/Várfok Gallery, Viki Régner

Máté Orr | Web | Facebook | Instagram

Várfok Gallery | Web | Facebook | Instagram

Tropical ecosystem in a Polish office

An electric moon-rover motorcycle designed for NASA