Gene therapy, once confined to science fiction, is now reshaping modern medicine by rewriting our DNA to cure previously untreatable diseases. Insight by Stanislav Andranovitš.

When we imagine the people of the future, our minds often conjure up cyberpunk visions: people with brain implants, artificial eyes, and mechanical limbs. However, sometimes it is worth turning our gaze inward, because the most ordinary solution may already be written into our own biology. The future of the superhuman is inscribed not in metal but hidden in the pattern of our genome.

As so often happens, science fiction writers were the first to explore the idea of reshaping human biology. Almost a century ago, Aldous Huxley in Brave New World (1932) depicted a society where humans were grown and designed in advance. Later, Isaac Asimov and other authors envisioned medicine that could correct hereditary flaws.

Today, these once speculative ideas are beginning to become a new reality. Gene therapy is no longer science fiction but a real medical technology capable of correcting DNA errors and even endowing cells with entirely new functions.

Gene therapy is among the most promising and vigorously developing trends of modern medicine. The principal concept of this therapy is correcting defects caused by mutations in the DNA sequence.

Every illness can be explained through genetics. Imagine you have poor eyesight. Instead of fixing it with laser surgery, what if you could simply replace the faulty stretch of DNA with a corrected version and suddenly see clearly? It sounds like science fiction, but gene therapy is already moving from dream to reality. Still, it’s far from simple.

Some diseases are caused by a single faulty gene, while others involve entire chromosomes. Think of your DNA as a book: sometimes the problem is just one wrong letter in a word, it is easy to fix. But sometimes it’s as if an entire chapter is written in gibberish. You can tear the chapter out, but then the story no longer makes sense.

Take Down syndrome as an example. It happens when a person has three copies of chromosome 21 instead of the usual two. That’s like carrying an entire extra chapter in the book of life. Right now, gene therapy can’t solve this kind of problem as it’s simply too complex. But for conditions caused by a single broken gene, the technology is already here and changing lives.

How do we get the right piece of DNA into a human cell?

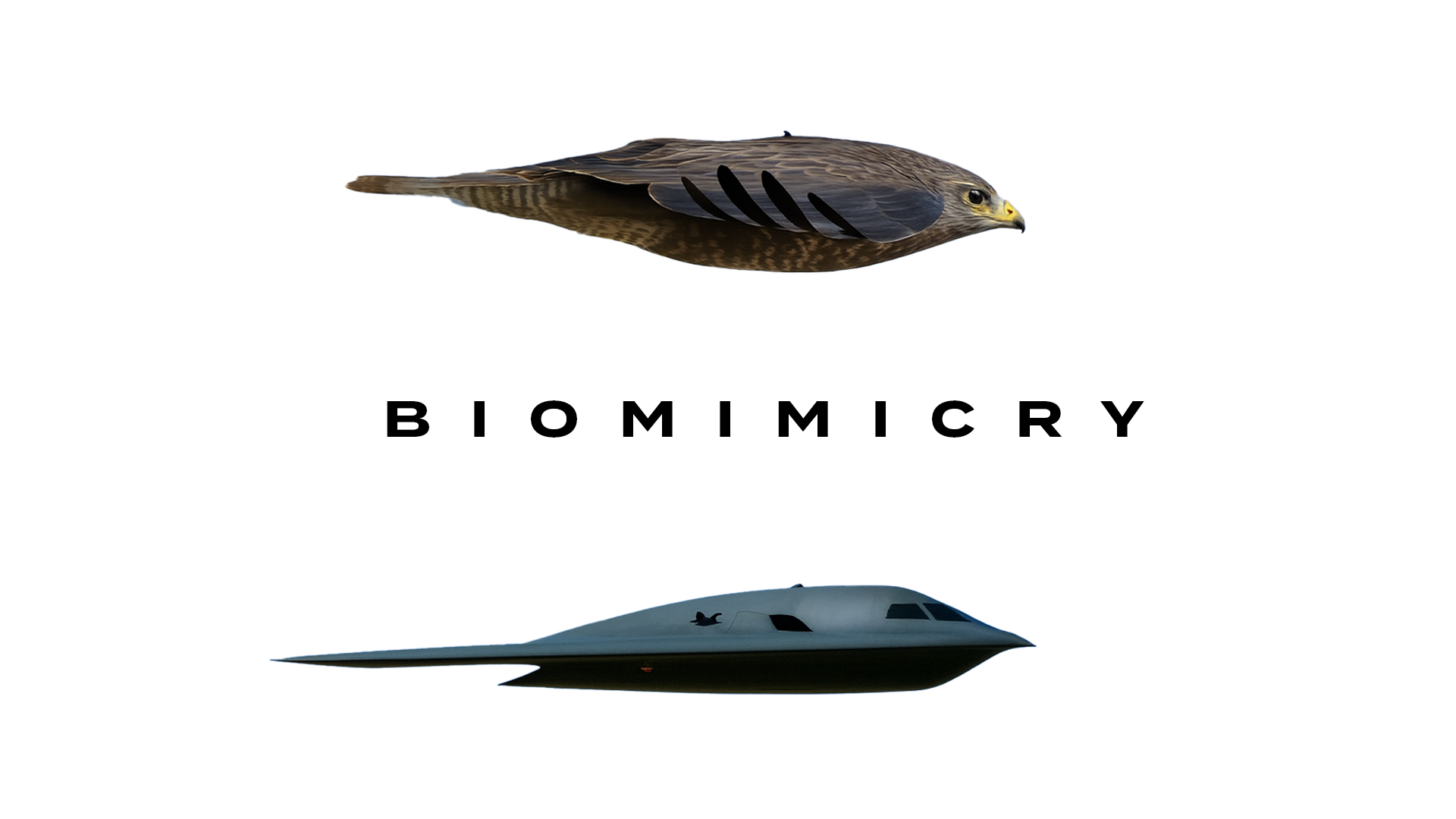

Sometimes, you don’t need to reinvent the wheel, nature has already solved the problem. This idea is called in science biomimicry. For example, have you ever noticed how burrs stick to your clothes? Scientists looked at that and thought, “Why not borrow nature’s tricks?” and invented hook-and-loop fastener. Or let's just compare a stealth fighter jet to a falcon.

The same approach has been used with viruses, which are a good natural solution for gene therapy. Many viruses, like HIV, are experts at getting inside human cells and even inserting their DNA into the cell’s genome.

In gene therapy, scientists take advantage of viruses as natural delivery systems but safely. The harmful viral genes are removed, and a therapeutic gene, such as one that can help restore vision, is inserted instead. The virus already knows how to enter cells, and now it simply delivers the healthy DNA, giving the cell new instructions without causing disease.

Viral vectors are incredibly effective and already used in medicine, but they are far from perfect. The body can recognize the virus and attack it, triggering unwanted inflammation and cause other side effects. Viruses also carry only a limited amount of genetic material. You can think of a virus as a tiny capsule carrying a package of DNA. On top of that, producing these virus-based drugs on an industrial scale is complex and costly.

Scientists have also proposed non-viral approaches for gene therapy. Nevertheless, as of July 2025, 35 gene therapy drugs had already been approved, and 29 of them relied on various viral vectors.

Medical miracle

As discussed above, gene therapy works best when a disease is caused by a mutation in a single gene. The RPE65 gene is only about „20,000 DNA letters” long, which is tiny compared to the 3 billion letters of the human genome. However, a single typo in this gene can mean the difference between sight and lifelong blindness.

Mutations in RPE65 cause severe vision loss or blindness from birth or early childhood. For a long time, this condition condemned people to a life without sight. However, the situation changed in 2017, when the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the first in vivo gene therapy for this inherited disease. The drug is called Luxturna. It delivers a functional copy of the gene directly to the eye retina using a specially engineered viral “courier,” and the results are remarkable: patients experience improved vision, and for some, it represents a return to a fuller, more independent life.

Gene therapy: how did it develop?

|

Year |

What Happened |

Why It Mattered |

|

1972 |

Scientist Theodore Friedmann suggests fixing diseases by replacing faulty genes |

The very first idea of gene therapy is born |

|

1990 |

A 4-year-old girl in the U.S. gets the first experimental gene therapy |

The start of real-world testing |

|

1999 |

A young man, Jesse Gelsinger, dies after receiving gene therapy drug |

A tragedy that almost stopped the whole field |

|

2003 |

China approves Gendicine, the first gene therapy on the market |

A world “first,” though widely used in China, it has not been approved in the U.S. or EU |

|

2017 |

Luxturna helps blind patients see again |

The comeback of gene therapy and a medical miracle |

|

2019 |

Zolgensma offers a one-time cure for a deadly childhood disease (spinal muscular atrophy) |

Famous as the world’s most expensive medicine (about $2 million) |

|

2023 |

Casgevy becomes the first approved treatment using CRISPR gene editing |

Marks the start of the genome-editing era |

Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) is another a rare disease caused by a single faulty gene. It weakens muscles by damaging the nerves that control movement. Babies with SMA often look healthy at birth, but within the first months they may struggle to lift their head, roll over, sit, or crawl. Without treatment, the condition can be life-threatening in early childhood.

Everything changed in 2019, when a gene therapy called Zolgensma was approved. It works by giving motor neurons a healthy copy of the missing SMN1 gene. This tackles the root cause of the disease. Zolgensma does not make children fully healthy, but it can greatly slow down or even stop the progression. Many treated children reach milestones that would be impossible without it, though some weakness usually remains. Starting therapy early leads to the best results.

Unfortunately, while this therapy gives parents hope, it is not a magic cure. Treatment can be accompanied by serious side effects, including fever, nausea, vomiting, low platelet counts, and others. In 2022, there were even reports of two children who died from acute liver failure 5–6 weeks after receiving Zolgensma. In this sense, gene therapy can feel like a high-stakes gamble, yet many families still hope for a miracle and a positive outcome.

Speaking about side effects, it is worth mentioning the famous case of Jesse Gelsinger, who had ornithine transcarbamylase (OTC) deficiency, a rare genetic disorder affecting the liver’s ability to remove ammonia from the blood. He received an experimental gene therapy using an adenoviral vector designed to deliver a corrected version of the OTC gene to his liver cells. Although he had a milder form of the disease and was otherwise healthy, Gelsinger experienced a severe immune reaction to the therapy and died four days later from multiple organ failure. This tragedy profoundly affected the future of gene medicine and led to stricter safety regulations and oversight.

When a Cure Costs Millions: The Price of Gene Medicine

Gene therapy can save lives, but it comes at an astronomical price. For example, a single dose of Zolgensma to treat children with spinal muscular atrophy costs nearly $2 million, and Hemgenix for hemophilia B is around $3.5 million per dose. The reason for those crazy prices is that developing such treatments takes decades and costs hundreds of millions of dollars in research and clinical trials. Manufacturing is also incredibly complex; it involves viral vectors or modified cells that cannot be mass-produced like ordinary drugs.

Many of the diseases these medicines target are extremely rare, so the price of a single dose has to cover all the expenses a company spent on development. We should also remember that the pharmaceutical industry is still a business: companies need not only to recover past investments but also to fund new research for the future. The high cost is further explained by the fact that these therapies are usually given only once in a lifetime, with effects that may last forever. Finally, strict safety and quality requirements add millions more to the price.

Government support exists only in rare cases and varies by country, so many families are forced to raise money through social media and charity campaigns. This makes gene medicine not only a scientific miracle but also a serious social challenge: a child’s life can depend on how widely their story spreads.

Gene Medicine’s Dilemma: Health or Privilege?

In 2023, the world saw the first medicine created with CRISPR technology. This technology is often also called ‘genetic scissors,’ since it can cut DNA at specific sites, allowing faulty sequences to be removed or repaired and normal gene function to be restored. The new drug, Casgevy, now helps people with serious inherited blood disorders that were once almost untreatable. And this is only the beginning: scientists believe we’re entering an era where rewriting our own genetic code may become possible. And it raises a big question: how far should we go in rewriting our own genetic code?

In his 1972 article, one of the earliest on gene therapy, Friedmann, often called the father of gene therapy, already highlighted the ethical challenges of the field, stating that “a sustained effort [should be made] to formulate a complete set of ethicoscientific criteria to guide the development and clinical application of gene therapy… to ensure it is used only where it will prove beneficial and to prevent its misuse.”

Like any new technology, gene medicine has its pros and cons. On one hand, it can save people from deadly diseases or disabilities, literally giving them a new lease on life. On the other hand, it raises the possibility that the rich or powerful might use it to “enhance” themselves not just for health, but for looks, intelligence, or physical abilities. This raises questions: who decides what is “normal” and what is “enhanced”? And how far are we willing to go before we start rewriting our own genetic code for privilege rather than for health?