The Vienna Biennale program series takes place in Vienna for the fourth time this year. Exhibitions running across multiple venues until early October aim to show—through a selection of works from the fields of art, architecture, and design—that our planet can still have a future if we act together now. Visiting the Museum of Applied Arts in Vienna (MAK), the organizer of the Biennale, we spoke to curator Marlies Wirth about the confluence of disciplines, speculative design, and collecting practices.

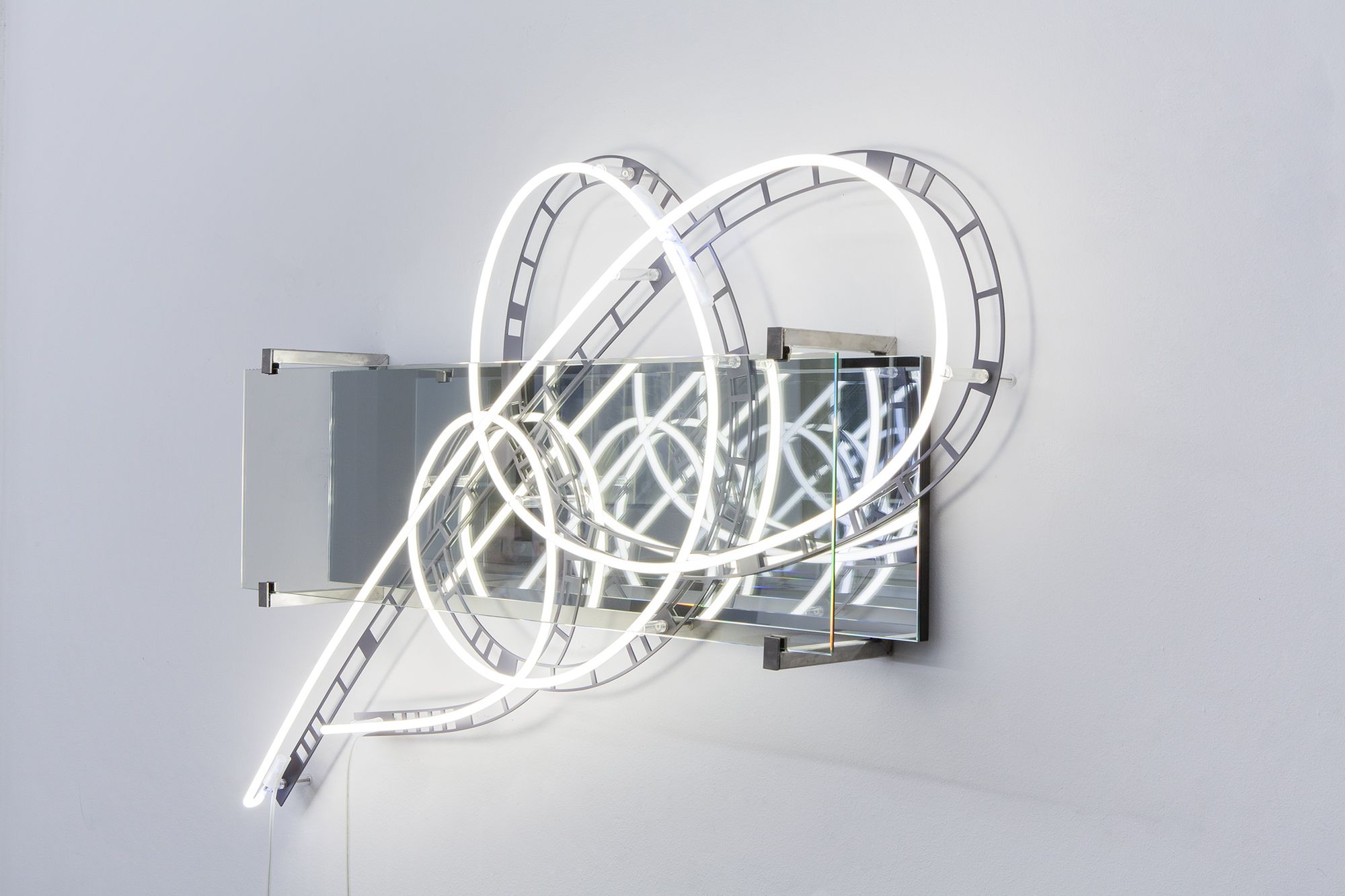

The leading exhibition of PLANET LOVE: Climate Care in the Digital Age, CLIMATE CARE, Reimagining Shared Planetary Futures, can be visited at MAK, starts with a strong opening: the work Amazon (2016) by Andreas Gursky immediately addresses one of the main problems, overconsumption, and next to it, as a counterpoint, a portrait of the heroine, Greta Thunberg, is drawn from blood cell charts. Alongside the artworks, research materials and utopian narratives will introduce the phenomena surrounding the climate crisis. At the same time, architectural and design projects will show possible ways forward to a future beyond human-centeredness. The only installation that breaks this dynamic is the site-specific installation of Superflux’s Invocation for Hope, which has an even more elemental impact after the repeated reports of wildfires in the recent past. The green oasis, hiding in the heart of a forest of more than four hundred burnt trees, shows that there is still hope—if we act now. Marlies Wirth, one of the co-curators of the biennale and head of the MAK’s digital culture and design collection, guided me through the exhibition. She explained that the aim of the 2021 series was to introduce a positive vision of the future after the somewhat dystopian, technology-focused exhibitions of the past. We asked her how contemporary art and design can help and how a design collection in an applied arts museum can engage in a dialogue about the pressing issues of our time.

Could you tell us more about the concept of the Vienna Biennale and this year’s theme?

The Vienna Biennale was founded by our director Christoph Thun-Hohenstein in 2015 with the idea of involving different Viennese institutions and other locations in current topics. He wanted to explore how historical museums could engage with contemporary issues. It is the only biennale in Europe—or even worldwide I guess—that involves three disciplines: art, design, and architecture. It focuses on interdisciplinarity and the claim, that all creative fields have to work together to tackle our current challenges with creative ideas and solutions.

The first biennale in 2015 was titled Ideas for change; in 2017, we worked around the topic of automation and digitalization in the context of human work and labor (Robots, Work, Our Future), and in 2019 we focused on artificial intelligence and the ethical values coming with it (Brave New Values). In that time, we already realized that these phenomena have a strong connection with climate change and environmental issues, so the next logical step was to dedicate this year’s events to the topic of climate change. It was not a new research area, my digital culture and design department researched these topics and expanded our collection with new contemporary projects around it since we redid the MAK DESIGN LAB in 2019. Still, we delved deeper during the preparation of this year’s Vienna Biennale (Planet Love. Climate Care in the Digital Age).

The previous editions with the theme of technology always had a somewhat dystopian side. Therefore in 2021—although climate change could be a dark topic as well—we wanted to create a new narrative and emphasize positive ideas, showcasing concepts and prototypes that can give hope and show how much can be done if we act now. It is time for the creative field, institutions, politicians, activists, and grassroots initiatives to work together to reshape our relationship with the planet and dream up a different future for the coming generations.

Visiting the exhibition Climate Care, we can feel that art, design, and architecture are not separated and being put into different boxes but make a fusion.

It was embedded already in the foundation year of MAK. In the past, MAK was named the Museum of Art and Industry, and it was always showcasing new production techniques. The idea of Gesamtkunstwerk in the 1900’s already entailed the connection of art, design, and architecture.

For the Vienna biennale exhibitions, these disciplines were precisely chosen because they can achieve very different things. Art projects can tackle topics from an emotional or provocative side. They can represent more conceptual and poetic approaches. Design projects can be actually usable and a visitor can easily say, ‘I could get that app’ or, ’I could use that product differently to be more climate-conscious.’ Architecture and urban planning projects are focusing on a larger scale, involve national strategies, for example, on how to build a sustainable city. Vienna is an excellent example of that—we have a great public transport system, and we are increasingly building more bike paths to encourage people to use their cars less. I know these could not work in every city like that, but it’s a great challenge to find ways to establish new, more sustainable ways to live together in an urban context.

This temporary show and the one from the MAK Design LAB also showcase contemporary art and speculative design projects. Has it always been MAK’s mission to represent these directions?

Contemporary art came to the MAK with the director Peter Noever who had started to transform the museum in the 1980s. He focused on strong contemporary art acquisitions and always claimed that design is thinking and design is everywhere. Christoph Thun-Hohenstein carried on his legacy and was challenging all of us curators here to involve art, design, and architecture projects together in more interdisciplinary ways. Regarding my view and curatorial approach, I embraced that. It is not enough to replicate common ideas around products—as a cultural institution you can also choose to be a role model and try new things, invite designers and artists to dare to speculate and see where the fictional approach might lead to in reality.

What are the main collection development principles of the design collection?

Everything that we collect in MAK is design, but we parted the contemporary design collection from the historic ones to focus on concepts, processes, design strategies, and technology-related (and also digital) projects. Of course, every recently made chair or ceramics is design, but we keep these in our furniture or glass and ceramics collection to keep the object types together for conservational, conceptual, storage, and research reasons. The design collection concentrates on Austrian design and specific objects that do not fall into the categories of our main collection areas. We focus on digitalization, climate care, new materials, strategic and conceptual design regarding research topics.

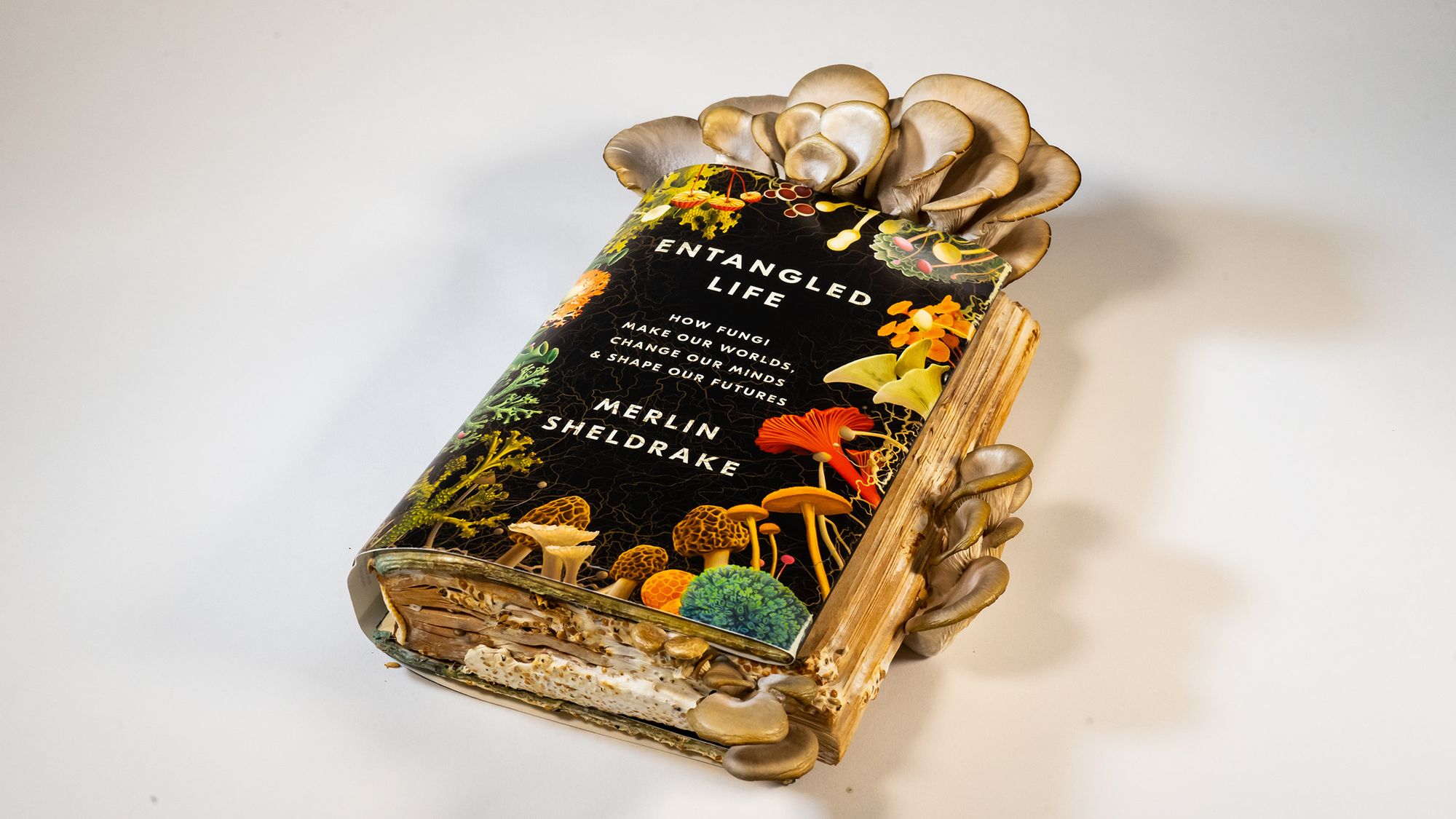

Do you also collect these previously mentioned idea-oriented or performative design projects, which do not always end up as an object, and if so, how can we grab their essence in an archive-compatible format?

We do, and we are doing that by also collecting photo and video documentation, manuals, concept papers, or manifestos and try to embed further readings and information in our database, which gives the context of that time. We have to think ahead not only 5 or 10 but 200 years, and we have to make sure that people in the future will understand what it was because things are changing fast. When MoMA collected the first set of emojis that was ever designed, they also needed to provide the cultural context of the emergence of smartphones and the arrival of social media and a new type of communication.

Do you have software-based works in the collection?

Not much yet, but we collected our first fully digital project, an OS screensaver from Harm van den Dorpel, in 2015. We also have the documentation of stills, screenshots, and notes about its programming as well. In addition, we have a machine learning concept by Process Studio for Art and Design—running on a Raspberry Pi— called AImojis, or AI-generated emojis. Digital projects are never intangible, they always need hardware. It is challenging for museums to provide the proper devices that will make it possible to run the software for the audience in 100 years, but I am sure there will be creative ways to find historic computers for them… maybe in collaboration with the collections of technology museums.

Design from Eastern Europe is also represented in the collections of MAK. Do you see characteristics in Central and Eastern European design which make the region’s creative scene significantly different?

I think we can always see differences and similarities if we want to. Last year I was on a jury of a graphic design competition in Bratislava where I noticed the use of different trends and fonts than what was common in Vienna in those days, but overall, I think the capitals of creatives in this region (Vienna, Budapest, Bratislava or Prague) are close to each other and represent similar ways of thinking. Do you see differences?

Not much in trends or quality, but I see that some tendencies, for example, critical or speculative design are more common in the UK or the Netherlands than in Eastern Europe.

That might be true, although I believe that has to do with the universities much more than the general trends. Some universities focus more on industrial design and craft. In contrast, others give space for non-functional design, for example, Design Academy Eindhoven or University of Applied Arts Vienna, where a whole course is called design investigations, led by Anab Jain, which was named speculative design before, led by Fiona Raby. It is a great way to teach students to think outside the box and really “investigate” alternative futures.

Supported by the ÚNKP-20-2-I-MOME-47 New National Excellence Program of the Ministry of Innovation and Technology funded by the National Research, Development and Innovation Fund.

Cover portrait: Marcella Ruiz Cruz

Vienna Biennale | Web | Facebook | Instagram

MAK | Web | Facebook | Instagram

HIGHLIGHTS | Looks matter too

The country's largest LEGO mosaic is ready | MOME x LEGO Hungária