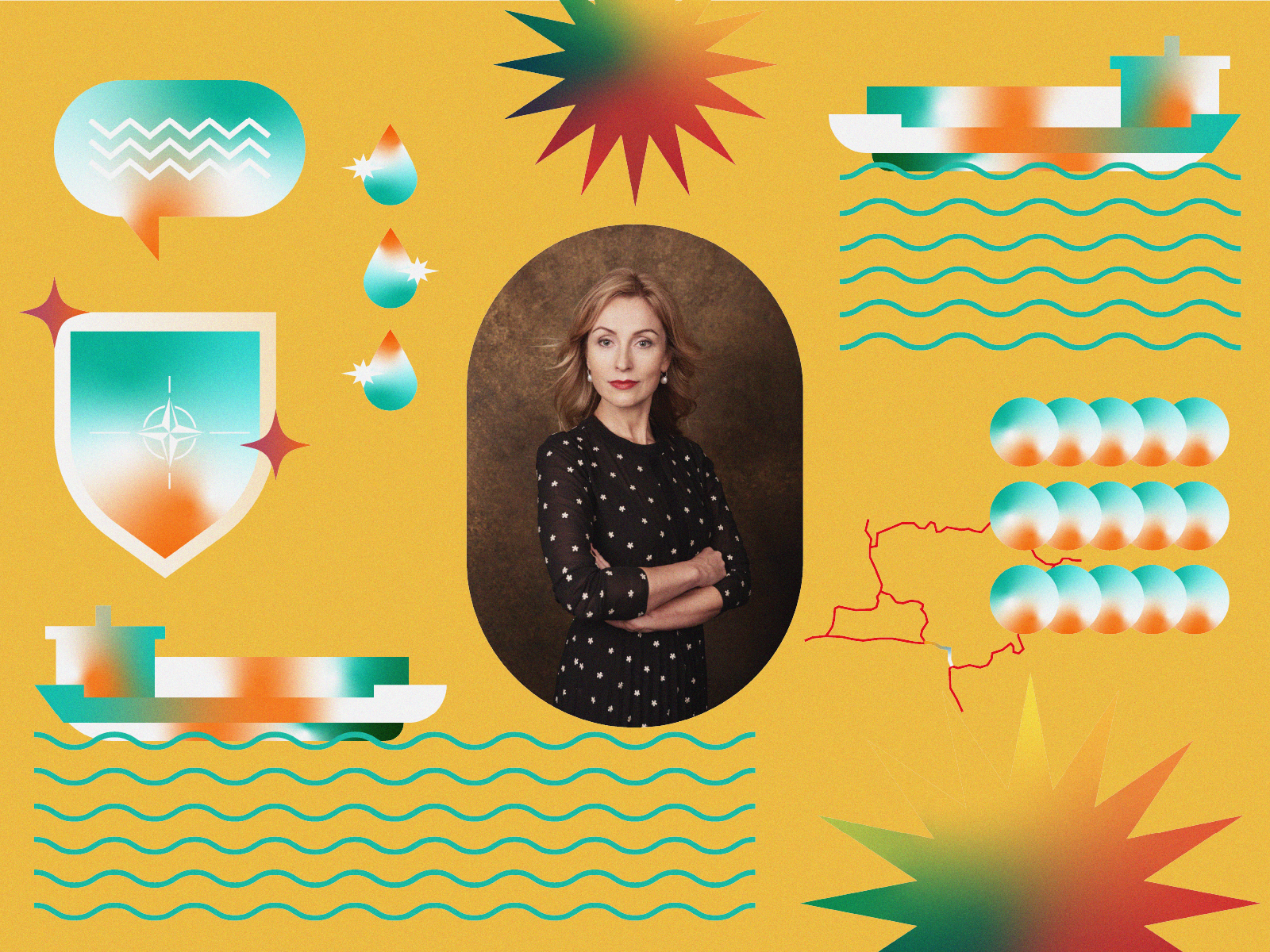

We have become the “voice” of pro-western Eastern European countries in Europe – Dr. Margarita Šešelgytė told Hype&Hyper on Lithuania. Interview about the Russian influence in Lithuania, the weaponized migration by Belarus, the Kaliningrad case, and Lithuania’s progressive China policy.

We can state that from an economic and geographical perspective, Lithuania is a small country, but right now, its role is quite significant: during the Russo-Ukrainian war, the Baltic states are a point of contact between the West and Russia; we could say that they are a battlefield in a sense. How would you describe the geopolitical situation of Lithuania before and after the war; was the 24th of February a game changer?

The security environment of Lithuania has been complicated since the re-establishment of its independence. Despite a very short time of relatively good relations with Russia during the Yeltsin era, Russia has never been considered as a potential partner as in many other European countries, but rather as a potential threat. Therefore, the NATO and the European Union membership was the biggest political victory in Lithuanian history and hugely impacted our security perception. That was the game changer, the tipping point. Besides that, our region’s geopolitical situation has always been relatively uncertain. That is why Lithuania and the other two Baltic countries have seen Russia for what it is since the nineties. Russia did not hesitate to intimidate politically and economically the Baltic countries on numerous occasions: economic blockade, energy resources blockade, political blackmailing, and weaponization of all sorts of vulnerabilities. We have realized that interdependencies with Russia are a potential risk and tried to reduce them. One of the examples is the LNG terminal “Independence” that Lithuania acquired in 2014. It allowed Lithuania to diversify its gas import. Another telling example is the cyber-attack on Estonia in 2007, which paralyzed the functioning of state institutions, banks, etc., for several weeks. Both examples also tell a story about the resilience of the Baltic states. The LNG terminal has allowed Lithuania to escape the curse of “energy island,” and Estonia, learning from the cyber crisis, has managed to become one of the most advanced countries in cyber security. The lessons we learned and the realization that Russia is becoming an autocracy led to certain foreign policy choices in Lithuania. On the one hand, we have become the “voice” of pro-western Eastern European countries in Europe. On the other hand, national security has become the key priority of our foreign policy. Lithuania fears that Russia’s geopolitical ambitions are increasing and might not stop at the borders of NATO. Lithuania is a small state, and the security of small states depends on a viable international system based on the principles of liberal democracy: the rule of law and equality between the states. However, the Russian vision of the international system is based on the rivalry between the great powers, interests, and zones of influence. Small states, as we are, are seen as objects rather than subjects of international politics. According to the Russian regime, the Baltic states are on the borderland of their political zone, which is why they think they have the right to influence our politics, economy, and society. The attack on Georgia in 2008 was the first alarm signal of Russia’s true intentions, and Crimea was the second. Lithuania has been vocal about both ever since. I would argue that the Russian war on Ukraine was not entirely unanticipated in Lithuania. We have been preparing since 2014 for something similar though maybe not of such a large-scale invasion. The events of 24th February just proved that Russia has the political will to wage a full-scale war. It is still unclear if it also has a political will to wage war against NATO. And therefore, we must prepare in advance to ensure that we have enough national and NATO military capabilities to meet Russian troops on the border.

You mentioned some security dilemmas, and most of the Ukrainian government stated that according to Russian propaganda, the next target would be the Baltic states and Poland after Ukraine. But in this case, we can also talk about the situation of Article 5. of the NATO Treaty. How do you think, is it an actual threat to the Lithuanian statehood in case of Russian victory in Ukraine, or is it just internal political communication to the mass of the Russian people?

At this moment, Russia does not have the capacity to sustain the war in Ukraine and, at the same time, fight with NATO. NATO’s Article 5. works and the major change after the 24th of February was the shift of perception in NATO, the realization that the defense concepts and forces deployed in the region do not match the changing reality. The Alliance must refocus from deterrence by punishment to deterrence by denial. As we lack strategic depth, Russian armed forces simply cannot enter the Baltic countries; otherwise, we might be swept from the ground. The Baltic states can be overrun by Russian troops very fast, and after witnessing the barbarity of Russian armed forces in Bucha and Irpin, it is clear that NATO cannot afford that. Although there are still several challenges related to the defense of the Baltics, these conceptual changes are very important. The potential Swedish and Finnish NATO membership will also impact regional security dynamics. The most precarious scenario for the Baltics is the one that involves a fait accompli situation and nuclear blackmail. Although the probability of this scenario is relatively low at the given moment, the damage would be devastating, especially if Putin would still consider it a political option aiming to confront the United States and make NATO lose. The forces on the ground in the Baltic states are still insufficient; there are also significant holes in our air defense system. Contrary to those who argue that the Russian Air Force is experiencing major losses in Ukraine and cannot be restored any time soon, I have to remind them that Russia is an authoritarian state. Its leaders do not care about human losses; new people are constantly being conscripted in various regions and even other countries. The Russian regime is not shy about using criminals in the war. Although sanctions imposed by the Western countries have affected several aspects necessary to assemble sophisticated weapon systems, Russia still can produce a lot on its own. Economic slowdown due to the sanctions might not affect defense spending.

You also mentioned the case of Kaliningrad. There was a confrontation between Lithuania and Russia because of the sanctions imposed by the European Union. After a few weeks, the European Commission clarified the details of the sanctions; right now, it is free to go in case of trade. If we want to explain the whole situation, how would you describe Lithuania’s responsibility regarding the Kaliningrad and Suwalki corridor case?

The so-called Kaliningrad exclave is another vulnerability of Lithuania that Russia might weaponize. The only way for Russian transport to reach Kaliningrad is through Lithuanian territory or the Baltic Sea. Land transport is cheaper and more reliable. Since Lithuania joined the EU, the EU legislation regulates any transit between Russia and Kaliningrad; the EU has primary responsibility for the free movement of goods. It is the EU Commission which is the primary agency in terms of implementing these legal regulations and decisions. The Kaliningrad problem as such was created by the fourth package of sanctions, which were approved in March. The sanctions forbade the transit of particular groups of goods from Russia to third countries through the territories of the EU members. A potential risk involving the Kaliningrad region was anticipated, but we were not yet aware of the details. The sanctions cover transiting goods to third countries, but in the case of Kaliningrad, the transport is between two parts of the Russian Federation. However, no one can be sure if Kaliningrad is the final destination of these goods. As I have mentioned, the potential challenges were discussed by Lithuanian authorities and the European Commission, but it was not sufficiently clarified. Russia, on their side, has sensibly manipulated this information and used it as a piece of propaganda both for internal but also external needs portraying Lithuania as the country that is just simply unilaterally blocking the transit of goods from Russia to Kaliningrad without specifying what kind of goods and harming Russian citizens. Whereas, in fact, when we look more closely, these sanctions have touched only about 1% of the whole transit, which goes from Russia to Kaliningrad, and involved only two product groups: steel and black metal. This crisis has presented Lithuania with a difficult dilemma. On the one hand, Lithuania thought history had taught us how dangerous it is to make concessions to Russia; moreover, there are quite high expectations in Lithuania that our foreign policy regarding Russia should be based on values rather than interests and that Russia should be punished for what it is doing in Ukraine in the harshest possible way. On the other hand, I do not think this issue is of such importance that it makes sense to have a major battle over it, which might split Lithuania and the rest of the EU and other partners. Handling this crisis through the European Union institutions increases the leverage of our position.

In this case, we can state that even the mainstream media follows the narrative of the Kremlin.

Of course, and that was one of the most interesting things to me. Major European media outlets contacted me during this crisis, and among other questions, I was getting the ones spun by Russian propaganda, such as “why is Lithuania blocking Russian goods?” Or “is this blockade a proportionate response to the Russian actions? And for me, it was very interesting that from where they were getting these narratives. It is clear that Russia, in a way, was winning with the prompt and overwhelming propaganda in the West.

Who is responsible for the Lithuanian communication in this case?

The Government, and the President. I believe the problem was a lack of a well-prepared, pre-emptive strategy of communication and a lack of coordination between various state institutions.

Belarus weaponized migration in 2020 and 2021 at the border of Lithuania. Do you still have this problem?

I think that we are better prepared. First, the physical barriers on the border are almost finished; moreover, we have learned how to address the issue, and finally, the flows are smaller.

Can it be an issue again in the future?

There are many preparations on the side of our Ministry of Interior and Border Guard. They are better equipped and have better knowledge now. During the crisis, there was very fruitful cooperation between the Lithuanian authorities and the European Union institutions, especially Frontex’s mission was extremely helpful. There were many lessons learned, so although no one can be entirely immune from large flows of immigrants and potential challenges, I believe we can much more effectively respond to this challenge in the future.

What is the situation with the mass of people who want to flee from Belarus because of the Lukashenka regime and those who want to escape from Russia through Belarus, mainly Ukrainian people who were transported from Mariupol?

Many people are still fleeing Russia and Belarus and coming to Lithuania. For instance, I signed the documents for Russian academics and students who wanted to cross the border to come to Lithuania. That is happening, and we already have a pretty big Belarusian, Ukrainian, and Russian community in Vilnius. We can state that the intelligentsia of Russia is trying to escape. It was happening for years, but I think the war was the tipping point. On the one hand, it has been unsafe for many to remain in Russia but also psychologically very difficult to live in an aggressor country.

The last topic is not about Russia but China because Lithuania has quite an interesting relationship with the Chinese. Lithuania was part of the 17+1 cooperation platform made by Beijing, but right now, it is called 16+1, and soon it is going to be 14+1 as Estonia and Latvia will also leave the group after Lithuania. Vilnius has a lot of ties with Taiwan, such as its representative office in Lithuania. Due to this interaction, the Chinese government started a frontal economic attack on Lithuania. Lithuania is the only country in the European Union that recognizes Taiwan. What are the advantages of this step?

Lithuanian position vis-a-vis Taiwan is the continuation of the idea that small states have to fight for democracy all over the world, as this is the only form of governance that allows small states to be subjects and not the objects of international politics. Fighting for freedom and democracy was important for Lithuania during the Soviet times and the first years of our independence. We did not want to become a boring province after we became NATO and EU members. We want to have a say in European affairs, in particular on the issues regarding helping less fortunate countries of Eastern Europe, which are not admitted to those organizations yet and are under constant intimidation from Russia. Another factor that has an important effect on our policy is our own security. Russia has always been a threat, and to keep it out of our borders, we need a close relationship with the United States. Realizing that the US interests have been pivoting to Asia and will continue to do so, Lithuanian decision-makers have broadened the geographical horizons of our fight for freedom and democracy. We have left the 17+ 1 format, were vocal in support of the opposition in Hong Kong, and decided to host “Taiwanese representation” in Vilnius, which according to China, breaches its one-state policy. Of course, this step has provoked a diplomatic reaction from the Chinese government, as well as economic sanctions and blackmailing European companies not to buy Lithuanian “parts.” But to tell the truth, I was impressed by the unified and quite harsh reaction to China on the European side. I believe this is the window of opportunity for the EU to set clear standards for cooperation with China to avoid similar situations in the future.

Assoc. prof. Dr. Margarita Šešelgytė is the Director of the Institute of International Relations and Political Science at Vilnius University. Before that, she worked as Deputy Director of Studies at Vilnius University IIRPS, for the Baltic Defense College (Tartu, Estonia), Jonas Žemaitis Military Academy of Lithuania, and the European Committee under the Government of the Republic of Lithuania.

The key to success is constant renewal, be it on stage or in the kitchen – An interview with Thomas Anders