“Live dangerously. Safety is often built on a world as imagined by authoritarian narratives and top-down control, rather than the reality as done by those getting on with their lives. Safety is just part of what we do, not the main focus of why we are doing it.” - Carol Jadzia Beauchemin, motorcyclist

We all know the iron and concrete playgrounds of socialism, where countless milk teeth fell out, heads got hurt, and accidents happened. I recently walked past a playground in Budapest that is now EU-compliant: special layout, covered bolts and iron surfaces, with safety taken to the max. This is not necessarily a bad thing–however, our safety obsession can, over time, cause huge social damage. Some scientists believe that modern society's obsession with safety is a direct pathway to the proliferation of mental illness. What has led to this? We asked Frank Füredi, the internationally renowned sociologist and author.

This article originally appeared in issue no. 8 of the Hype&Hyper print magazine.

Safe nursery, safe transport, safe spaces. Since when are we, safety addicts?

What has happened is that in the Western world gradually, safety has become a value in and of itself. Whereas before, safety was seen as something that was a consequence of good medicine or the consequence of secure borders. Today, the meaning of safety has expanded so that virtually every dimension of life comes with a health warning and every human experience has got a medical label attached to it so that if you're shy, you are diagnosed with social phobia. If you're very active, like me when I was a child, you have attention deficit syndrome. There is a situation where we medicalise life. What my research shows is that the more you care about safety, the less safe you feel. That's the paradox of safety and that's why we have a situation in which many parts of the Anglo-Saxon world are trying to create so-called safe spaces. Of course, if you have a safe space, you already have created the logic that anything outside of your safe space is unsafe. That's a trap.

The phenomenon has been described. However, if we want to understand the anthropological reasons in depth, at what point did European society start down this path?

I think it began in the late 1970s when the human condition was seen in a slightly different way, partially because of the exhaustion of the old ideologies, and the old political ways of interpreting the world. What happened was that the meaning of what a person or a human being was got gradually redefined. From an anthropological point of view, the word personhood is defined by cultural norms, such as how much risk you are prepared to take, how much challenge and difficulties you're expected to put up with, and how much responsibility you can put on yourself. Every culture gives you different answers. In the late 1970s, we began to psychologise human existence and one of the key messages was that people are defined by their weaknesses, their powerlessness and their vulnerability. If you are vulnerable, if you are powerless, then of course it also means that we cannot expect you to be challenged, we cannot expect you to take risks, we cannot expect you to be criticised. That was the beginning of insulating people from the pressures of everyday life. The more you do that, the weaker you feel and therefore nowadays a lot of young people are scared to grow up: they still think of themselves as being boys rather than being men or girls rather than being women. We've created a world where people think that they cannot do something for themselves without help from an expert. We have marriage counsellors, sex therapists, life coaches, parenting experts, and a whole army of people who deal with your personal problems. You are not expected to solve things by yourself, you lose your sense of responsibility and that's a tragedy. I push my students as far as I can. Not because I am a pushy person but because that's how you find your strengths and weaknesses. When you are reluctant to do that, it's called academic bullying. We need a new method of raising children and education in order to ensure that future generations are educated on the value of courage rather than dependency.

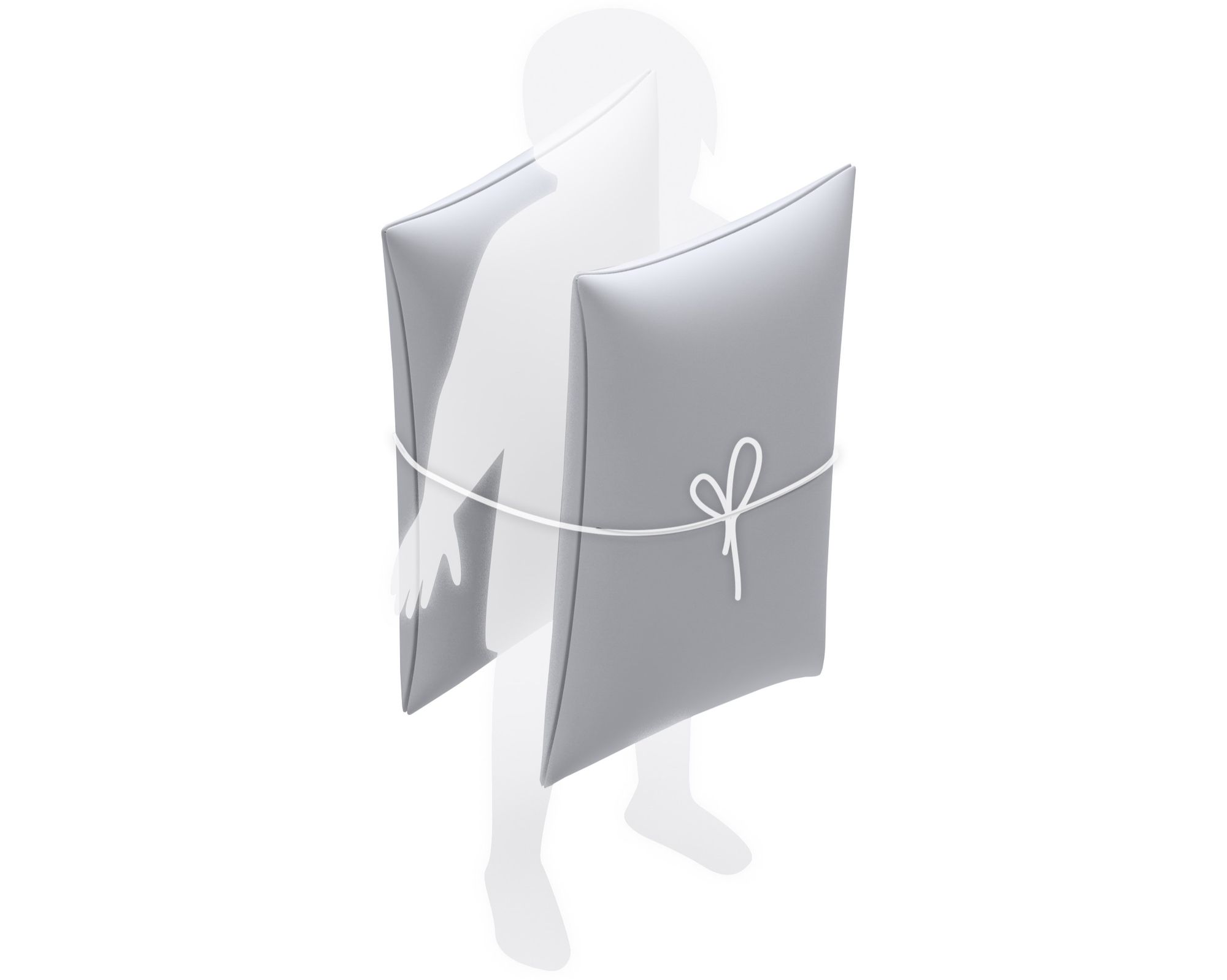

One of the most interesting areas of safety obsession is the transformation of urbanism. In the 1970s, American architect Oscar Newman coined the concept of defensible space, which became an increasingly important starting point for urban planning in the decades that followed, not only because of the fight against terrorism. The idea of creating defensible spaces comes from “making cities more liveable for consumers and less liveable for other people”. What does this mean in practice? Spikes installed in doorways to protect them from the homeless, high walls and fences, public litter bins disappearing because of litter bombs, or benches in parks where you can't lie down. In this concept, “we are redesigning the city so that anyone who cannot move is considered a threat”, including people with disabilities or even pregnant women. Today, secured by design is starting to appear in every single case, be it security camera stations, high fences or concrete elements hidden in the environment. While these can be integrated into a non-recognisable environment, it is difficult not to get the feeling that modern cities are in fact over-secured fortresses, whose surroundings ultimately create a sense of anxiety rather than security.

One would think that this is mostly a feature of Western societies, but if you look at the Far East, South Korea, Japan, and China, there is a constant fear in people there too. If there is a school shooting or perhaps a mass accident in China, a collective social psychosis sets in, even on social media, which sweeps everything away. Does this mean that this phenomenon has evolved with the modern world?

This is an interesting topic; I wrote a book in 1997 called The Culture of Fears and at that point, I noticed there was a big difference between risk aversion in the West and more risk-taking attitudes in Asia. When I talked to people in Singapore or China, they would ask me: is it really true that the West is like this? There was a great fear of taking risks as a result of media culture, and American soft power. A lot of these values get communicated to the rest of the world, particularly in the middle classes in places like Mumbai or Beijing where the society begins to adopt and act in a very similar way. In a place like China, where you have a very predictable and unchanging regime of control and regulation, when something disrupts that sense of taking everything for granted, people are shocked which is quite specific to Asian culture. What's happening today is that the two things I've described are coming together: the Western sort of risk-averse and safety-obsessive culture is mixed with the more Chinese kind of reactive, over-the-top reaction, and it's creating its own synthesis.

Frank Füredi is a Hungarian-Canadian academic and emeritus professor of sociology at the University of Kent. He is well known for his work on the sociology of fear, education, therapy culture, paranoid parenting and the sociology of knowledge.

Illustrations: László Bárdos

Continue reading H&H issue no.8!

ORDER HERE

On the same latitude as Burgundy: a sparkling wine champion from Transylvania

You're also in it: the Sziget aftermovie has arrived