We’ve heard about textile designers a lot, but not so much about people growing (!) textiles. Like many in her profession, Anett Papp started out as a traditional textile designer, but in the focus of her PhD research, she put a project where nature takes over the textile’s place in an extraordinary and spectacular way. Introducing the NATURING project.

Nowadays, we come across initiatives in the field of design where designers around the world are using banana leaves, coconut fibers, mushrooms or even orange peels to create objects—here are countless experiments in materials (thank God), and in the age of climate change, it’s almost obligatory. Most of these projects explore alternative solutions in the spirit of sustainability, so that the user can enjoy a biodegradable lampshade (such as Zsófi Zala’s Harm less brand) or a comfortable outdoor furniture collection (such as the recently launched CoTangens furniture collection designed by Sára Kele). In this kind of experimentation, the material undergoes some kind of processing: in the end, an innovative raw material is given to the designer, who then shapes it as desired according to the function of the object conceived.

But it is not only in this form that nature returns to design. Proof of this is textile designer Anett Papp’s PhD research, called NATURING, in which wheatgrass plays the leading role.

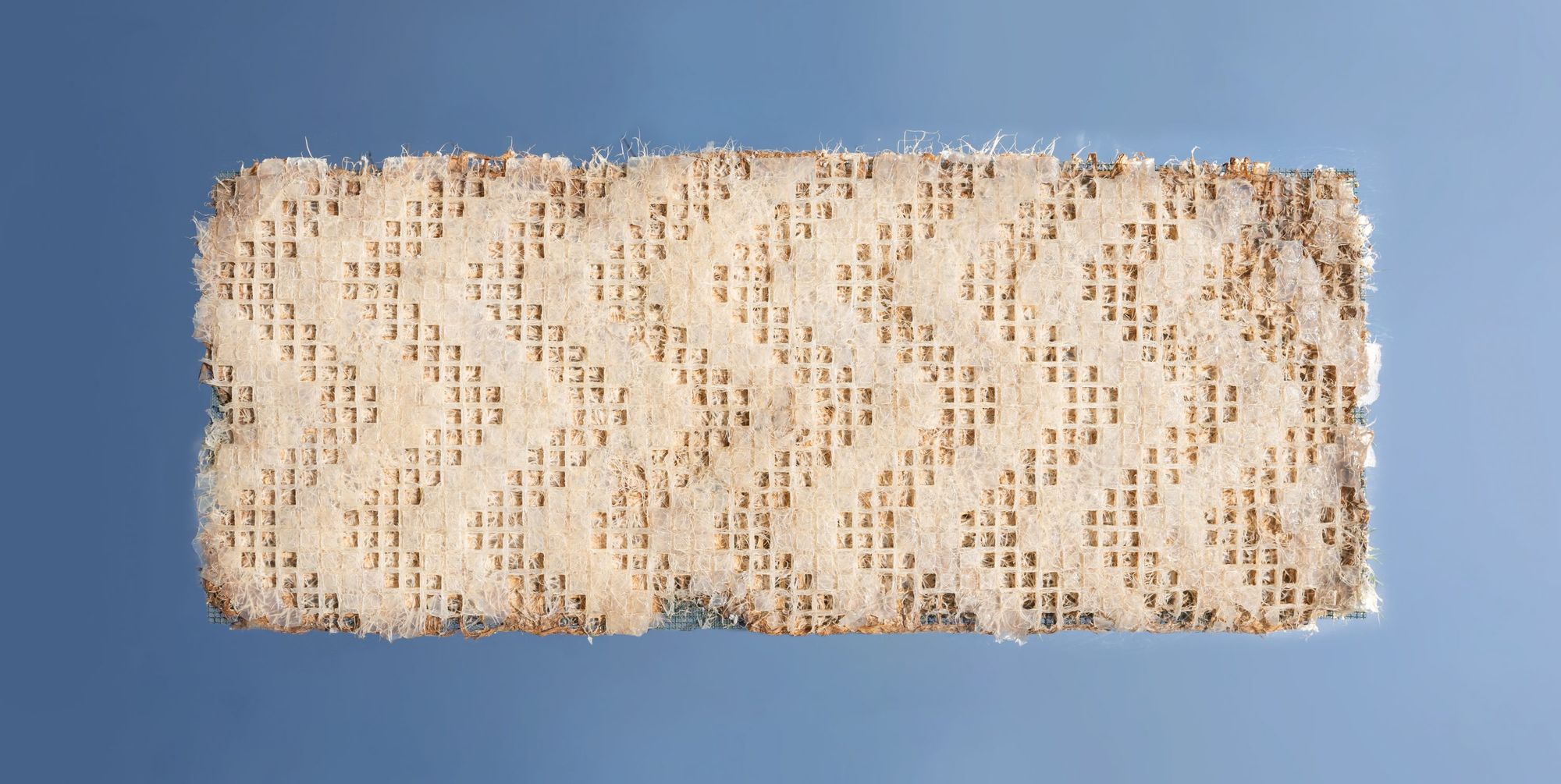

What do we see? We have a seemingly ordinary wheatgrass carpet, but its back isn’t a homogenous surface like we’d expect, but a flawless, waffle-like structure, ornated with different geometrical shapes (we can hardly expect to see any roots in this case). The usual substrate of lawns is completely missing here (or is it?), the patterns are drawn by the dense root system. How’s that even possible?

Anett Papp has always been interested in different weaved structures, she even used a live plant for her Master’s thesis: she wove lawn strips into the elements of a vastly enlarged structure. “I found this profession, or more precisely its connecting points very exciting, and I find that this is what determines my way of thinking to this day. A perpendicular system of yarns is only built up into a textile if there is yarn friction along some intersection points. These points of intersection are of crucial importance, and this is what gives rise to the motif itself, the different qualities of the structures, and the quality of the fabric,” Anett shared.

As a textile designer, she’s always been wondering how to create a textile structure without using traditional textile raw materials and yarn. Her PhD is an artistic research that resulted in this extraordinary collection, considered by Anett as primarily an autonomous work:

“The process in which I cooperate with the plant, where the plant creates the fabric, can be considered as the result of my work. The work itself that is produced consists of an above-ground unit, which is the green stalk of the wheat, and an underground unit, which is the root system of the plant. I can say that my plant has actually grown to a co-creative level over time,” she says.

According to Anett, the output of her PhD thesis is not just the ensemble of objects she has made, but rather the process of making the plant as a medium and co-creator, and the designer as a farmer. This new design attitude is embodied in textile growing, or Naturing.

It was hard for me, too, to label this object (Project? Item? Piece of art? Space textile?), and Anett mostly refers to it as plant textile, while she calls the process itself textile growing. “Many people deal with biological raw materials, but not so many with plants, at least not in the sense of creating textile by growing plants. This is called textile growing,” she explained.

Anett has experimented with many plants before picking wheatgrass, which is perfectly applicable in household conditions. She consulted with gardeners and horticultural engineers, but she never wanted to become a gardener, she remained a textile designer. As an amateur gardener, it was easier for her to work with a plant that has a looser planting density and is resilient at the same time. “I decided not to carry out my work in a lab, I wanted to connect it in my own home. I separated a very bright room where I basically created a greenhouse, which could be sterilized. I bought a planting table, it became my weaving loom,” she reveals. But how did she manage to create such a special, patterned, literally organic carpet?

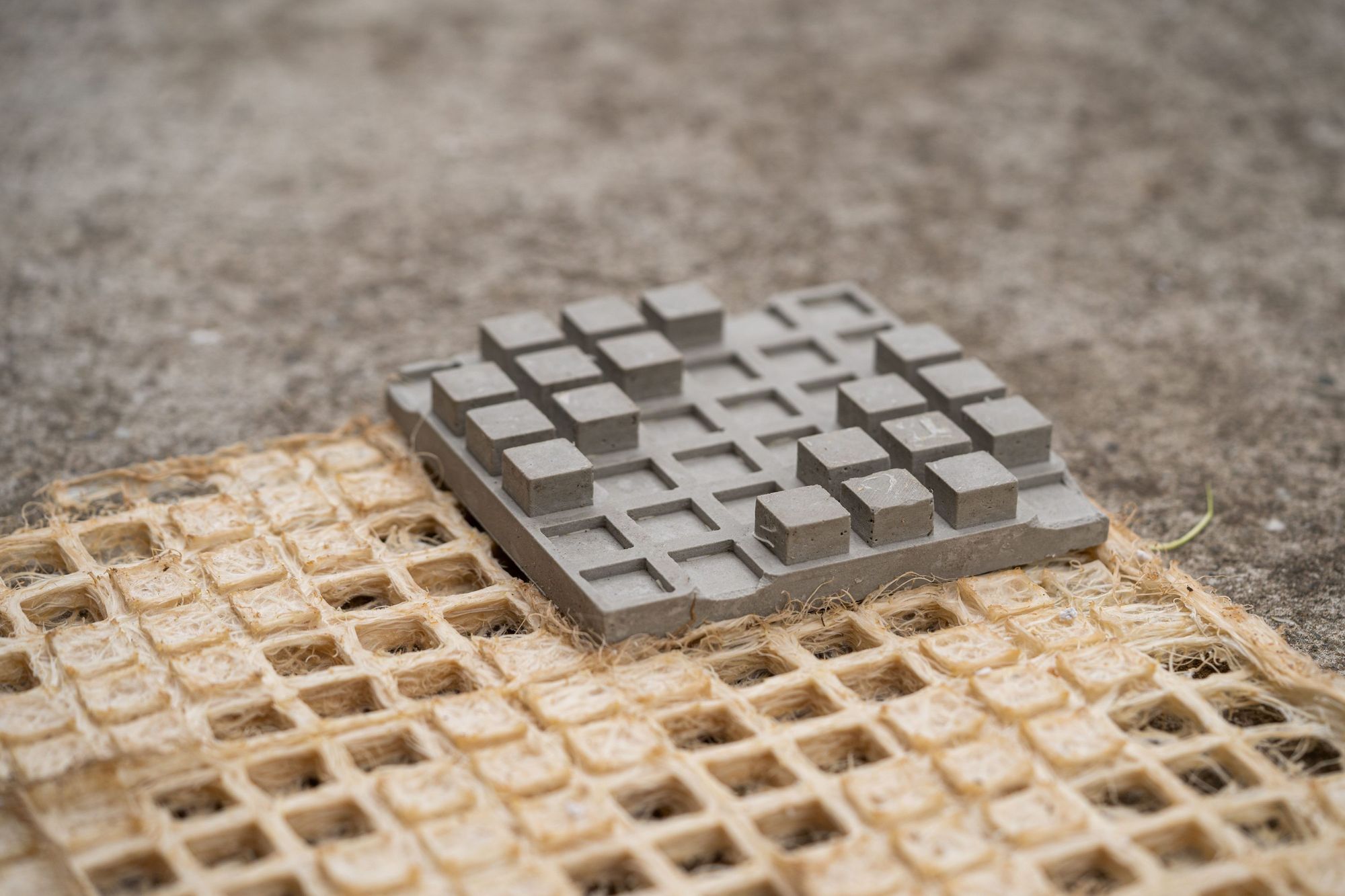

First, Anett designs the motif. The sample set is an enlarged weaving pattern that maps out the weaving system (a binary system that indicates the position of the fibers in the fabric). The finished sample is printed using a 3D printer, and a positive plaster cast is then made from this negative mold. As the designer pointed out, plaster is suitable because it can be easily reproduced – Anett arranges these 20×20 centimeter plaster tiles side by side and covers the (roughly two meters by one and a half meters) planting table with them. This is the basis for the planting medium she has constructed, a regular structure in which the wheatgrass seeds are placed.

However, the plaster mold’s tunnels do not place the seeds in just any soil, but in an unusual planting medium, agar-agar. Anett says that this wet gel is very practical: it is usually used for germination, it is completely absorbed by the plant, the plant decides how much moisture it uses from the agar-agar, plus the consistency of the gel makes it a translucent medium, so it’s easier to observe the development of the roots and their attachment. At the end of the process, usually after two weeks, a fine film of agar-agar is left behind and can be easily turned out of the mold.

In this situation, Anett can monitor the growth of the wheatgrass every day, regulating the plant’s growth and shoots, and controlling the amount of moisture, light and nutrients it receives. So, the designer is the creator of the structure and pattern of the space, who then takes a step back and lets nature do its work. „The root system doesn’t do anything differently from what it normally does. Think of it as if we were groping in the dark, in a field that is completely unknown to us, trying to assess the situation on the ground. The plant does pretty much the same thing: it reaches out for nutrients wherever it finds open space. When it encounters an obstacle, it changes strategy and moves to a different direction. By exploiting this momentum, in fact by replacing clods and pebbles in the ground, I can create spatial situations in which the plant’s root system surveys the terrain, creating a three-dimensional spatial structure. During the two weeks when the planting is done and I’m waiting for the wheatgrass to grow, I can no longer intervene in the process,” she says.

But exciting things are happening not only with the root, but also with the green stem of the plant: this surface, as Anett says, in the hands of a designer, is a canvas, because if I block the sunlight, yellow stem cells are born, and if it gets the sufficient light, green ones are born, and the direction of the light is not secondary, so the designer can operate with it to influence the direction of growth.

The PhD research has come to an end, but the work is not at all done: there are numerous different directions this plant textile can go on, depending on how we see it; as a work of art or as a design project (I both envisioned a new quality, artistic green wall and was reminded of the space textiles of the artists of the Velem Workshop for Creation of the seventies and eighties.) Anett says she hasn’t decided yet which direction to choose. “This is a completely new project with brand new qualities. We aren’t aware of all its parameters, I can only give answers based on my experiences. Meanwhile, it’s not really worth examining these qualities before knowing what we’d like to use it for,” she pointed out.

In any case, based on the above properties, the question is: where does this plant textile find its place? In a museum? If so, it is already a museologist’s nightmare, the difficulty of conservation (by the way, Anett’s three objects showing different stages of the plant’s life cycle are also on display at the “Common Space | 2nd National Salon of Applied Arts and Design” exhibition at the Kunsthalle—here the ephemeral nature of the object is most prevalent, and the temporality of the plant’s life cycle becomes part of the changed design attitude. As part of an outfit, a communal office or waiting room that can then be easily composted? These all raise many questions about usability, lifespan and much more. In any case, whatever direction the NATURING project takes, we will certainly be hearing more about it.

Photo: Dániel Ludmann

Anett Papp | Instagram

A holistic wellness space with a new approach

Photographs mirroring the Rorschach test