The “Othernity” walking tour series organized by Contemporary Architecture Center continued with another iconic building. The OKISZ Headquarters located at Thököly út offers several peculiarities visitors, including the paternoster lift operating unto this day, which – of course – we tried, too. What else does the brutalist building offer? Let’s see!

The OKISZ, i.e. the headquarters of the former Országos Kisipari Szövetkezetek (Association of the Hungarian Small-scale Industrial Cooperative) (later: Magyar Iparszövetség [Hungarian Industrial Association] – the Ed.) is undoubtedly one of the odd ones out in the villa district of Zugló. The office building displaying Brutalist features does offer an odd view next to the bourgeoise villas and the neighboring neo-Gothic Queen of the Rosary Church. The headquarters of OKISZ in Zugló ended up in a sophisticated milieu at Thököly út. It is directly enclosed by a Dominican church and a row of villas. It would have been an impolite discourtesy to rival with any one of them according to architectural etiquette. However, it had to be built in style, as its environment is full of recognized buildings. And of course it is the center of the industrial cooperatives of the country, a reference building of the sort, to show the standard according to which we do our work around here, represented by the headquarters” – says Népszabadság in 1984.[1]

The building was designed by János Mónus, contracted by ÁÉTI, Általános Épülettervező Vállalat (General Building Design Corporation). To be more specific, Mónus was only supposed to prepare the working drawings of the building planned to be built at the lot under Thököly út 58-60, as Mónus’ head of department, Dezső Dúl was asked to design the OKISZ Headquarters originally. However, the working drawings were not enough for young Mónus, and so he proposed the designs of a cascading building with a reinforced concrete frame instead of the tower house envisioned by Dúl. The architect not only had to bear in mind the church building consecrated in 1915, but the monastery stretching in the back of the lot, too, when designing the headquarters (the latter was designed by the famous architect duo consisting of László Lauber and István Nyíri in 1936). Taking the scarcity of space into consideration, all Mónus could do was to build the new headquarters directly next to the monastery. The OKISZ Headquarters was built between 1971 and 1973, and Mónus won the Ybl Award for his work in 1974.

Art historian Márta Branczik, the head of the Kiscell Architectural Collection of the Budapest History Musem leading the tour knows the headquarters quite well. In the framework of the Virtuális leletmentés (Virtual artefact salvaging) project initiated by her, the extremely detailed photo-documentation of the interior of the building was already prepared in February last year.[2] Branczik not only presented János Mónus and the circumstances of design to the audience, but she also talked about the relation between Brutalism and Modernism, as without clarifying these concepts, the Mónus building could hardly be put and interpreted in context.

The Brutalist architectural style, started in England in the 1950s, is closely linked to Modernism, but in addition to the well-thought out structure, materiality gains a greater role in the former. In addition to transparent glass surfaces, the emphasis is placed on wood, brick and, of course, concrete in its raw form (this is where the name of the style also originates from, the French „beton brut”, or raw concrete). In the case of Brutalist buildings, we tend to think of them as boring monstrosities, however, if we take a closer look at these buildings, we realize that they include many tiny loveable and decorative details that are designed in harmony with the entirety of the building and which make the overall look of the same quite exciting.

It is no different in the case of the OKISZ Headquarters, either. “It is made of two types of materials. White cast stone and glass, keeping the same atmosphere in both the inside and the outside spaces. The 4-story, cascading large-masse building was moved by designer János Mónus in a manner to keep the mass from being felt as much as possible, and to keep its vivacity from being to dominant in this quiet milieu. Only the vertical stone lamellas allow for some freedom, as light and shadow play on the facade, vibrating according to the time of day” – says Népszabadság.[3] The white cast stones reached their final form with the help of Kőfaragó Vállalat (Stone Carving Corporation) also working on Hotel Intercontinental at the bank of the Danube.

OKISZ welcomes its visitors with an elegant and spacious hall. The walls are clad in ash wood, and the floors are coated in elegant white marble – luckily not only these, but several other accessories, interior design elements and furniture were preserved in their original condition. The collection of plaques and medals from past decades can be seen on the wall of the hall („Cooperative Tailoring Contest”, „Hairdressers’ Contest”, „Shoe modelling competition”, etc.). “The task of Országos Kisipari Szövetkezet was to supply the small industry with raw material and to incorporate it into the planned economy through the co-operative movement” – defined Minister of Transportation and Finances Ernő Gerő the competence of OKISZ in 1948.[4]

According to Márta Branczik, probably the exhibition showcasing the activity of small industry workers was supposed to be placed in these ground floor rooms – or at least this is what the designs of the wall reveal in certain places. The soft curvatures also recur on several other points of the building: including the metal elements of the stair railings – these and many other elements were designed by János Mónus himself, and even though officially József Gampel was in charge of interior design, Mónus also designed the lamps of the cloakroom on the first floor and the metal-covered coating elements hiding the heaters, too.

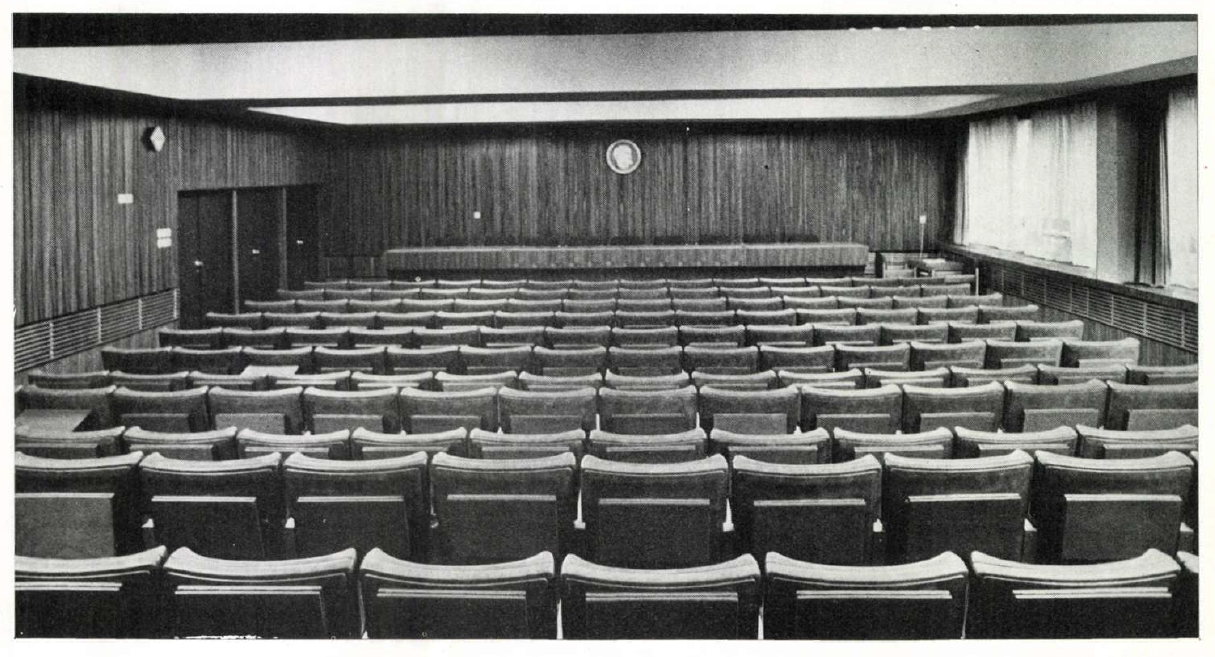

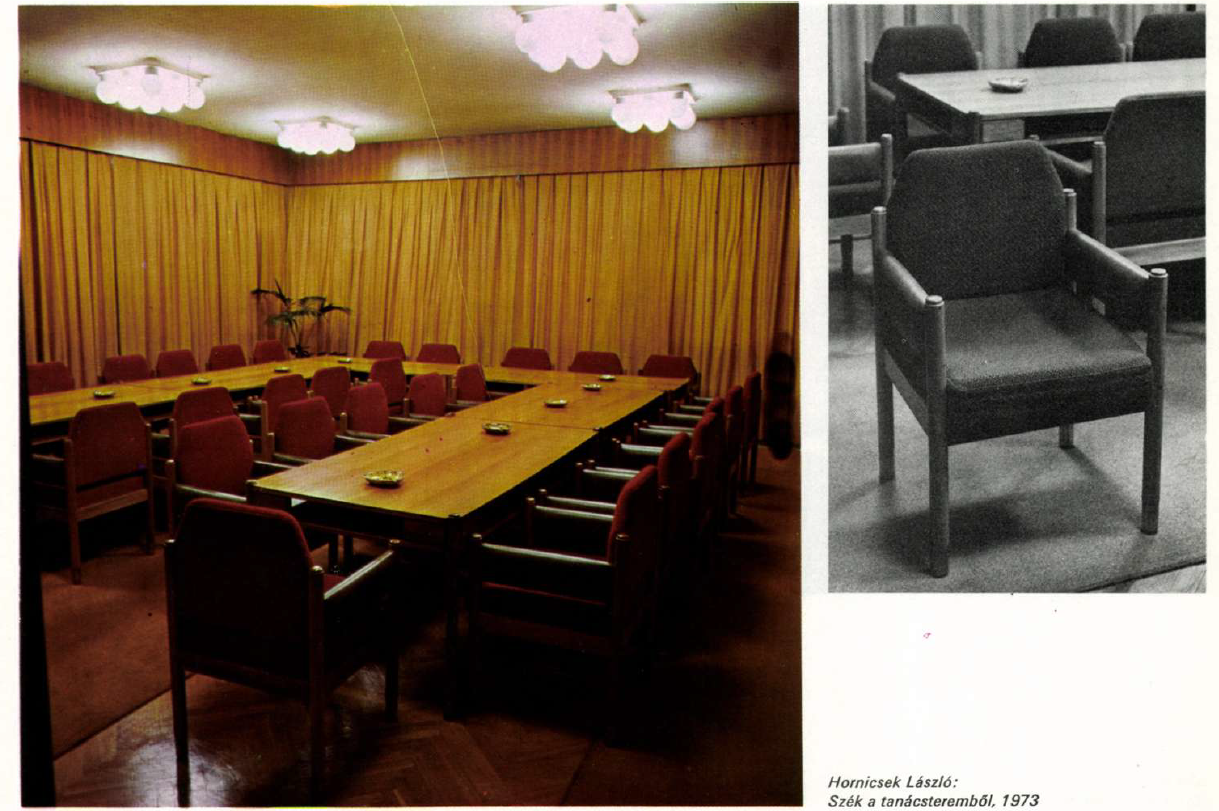

The chairs found in the offices and other meeting rooms of the headquarters were designed by László Hornicsek, who also designed the comfortable chairs located in the lecture halls covered in textile and leather – they even let us try these (we liked the tip-up tabletops fixed to the back of the seats facilitating notetaking the most).

Fun fact: as portrayed by the photo published in the periodical ‘Művészet’, the rows of chairs were designed without adding a central corridor, while currently, we can see two separate seating blocks (the row of chairs only becomes contiguous in the ninth row). Those walking in the room could also watch videos displaying one of the gems of English Brutalism, Barbican Center in London, amongst others, but we could also see several Brutalist examples from the United States and other countries around the world.

We also took a peek into the meeting rooms on the upper floor: here we saw walls clad in fine wood, and even though Hornicsek’s chairs aren’t here any more, we can still see the tables designed by him at the time. These rooms are structured in a simple and well-thought-out manner: the hangers fixed to the walls near the door served the comfort of the invitees of meetings, and there was also sufficient room for preparing the equipment necessary for coffee breaks comfortably without disturbing the participants of the meetings. Our eyes were also caught by a gorgeous tapestry in one of the rooms portraying the church nearby, but unfortunately we couldn’t learn more about the origins of the piece, yet.

The greatest hit amongst the participants of the tour was undoubtedly the paternoster lift. OKISZ also has a traditional elevator at the moment, this is generally used by the tenants of the offices, but the paternoster was also put in action for our sake. Another fun fact: neither children under the age of 10 nor disabled persons (or as displayed on the information table: “physically defected”) can use the elevator.

At the end of the tour, we were guided to the rooftop terrace, where we were able to take a closer look at the brick-fronted monastery attached to the headquarters, and we could also explore the stone lamellas, lined up next to each other and ensuring the dynamics of the OKISZ building depending on light conditions in more detail.

The building has been for sale since April last year. As it was also featured on the ‘Urbanista’ blog at the time, the purchase price of the real property was estimated to 1.8 billion HUF in the spring of 2019 (we have no updated information as to the current price of the office building – the Ed.). Nevertheless we can agree with Dávid Zubreczki, the author of the blog, who referred to the former OKISZ Headquarters as “the most exciting Brutalist gem of Budapest”. Due to the high interest, KÉK plans to repeat the tour in the future, so anyone who missed it this time should keep an eye on KÉK’s Facebook page.

Photography: Balázs Mohai

In our series we tell our readers about the walking tours organized by the Hungarian Contemporary Architecture Center (KÉK), in relation to the “Othernity” project. The “Othernity” project presents 12 iconic buildings of the modern architectural heritage in Budapest through the lens of 12 contemporary Central-Eastern European architect studios. How and in what manners the contemporary groups reinterpreted the emblematic buildings of Budapest will be shared with those interested in the Hungarian Pavilion of the International Architecture Biennale in 2021.

[1] ANTAL Anikó: „Szép házak dicsérete 2.” (Modern Építészet). Népszabadság, July 21, 1984., p. 6

[2] The ‘Virtuális leletmentés’ was an architectural artefact-salvaging project: they primarily documented the interiors of office buildings and public buildings in the form of photographs, thus preserving (even if only on a visual level) the outstanding, important and interesting items of our built heritage.

[3] ANTAL Anikó: „Szép házak dicsérete 2.” (Modern Építészet). Népszabadság, July 21, 1984., p. 6

[4] Magyar Ipar, September 15, 1948, Volume II, Issue 17 p. 22

Photo essay on Bosnia-Herzegovina’s marvels