The man who is a bigger Putinist than Putin himself. Analysis by Brittany Pheiffer Noble, Ph.D.

The ongoing Russo-Ukrainian war started more than a year ago, and while for the West, it is evident that the Russian aggression against Ukraine is wrong, it would be naive to think that most Russians also see the plight this way. Of course, the root cause is not the Russians’ inherent malevolence or perception of superiority: The mass media’s all-encompassing propaganda and the systematic spread of certain ideologies are pervasive and justify Putin’s aggression.

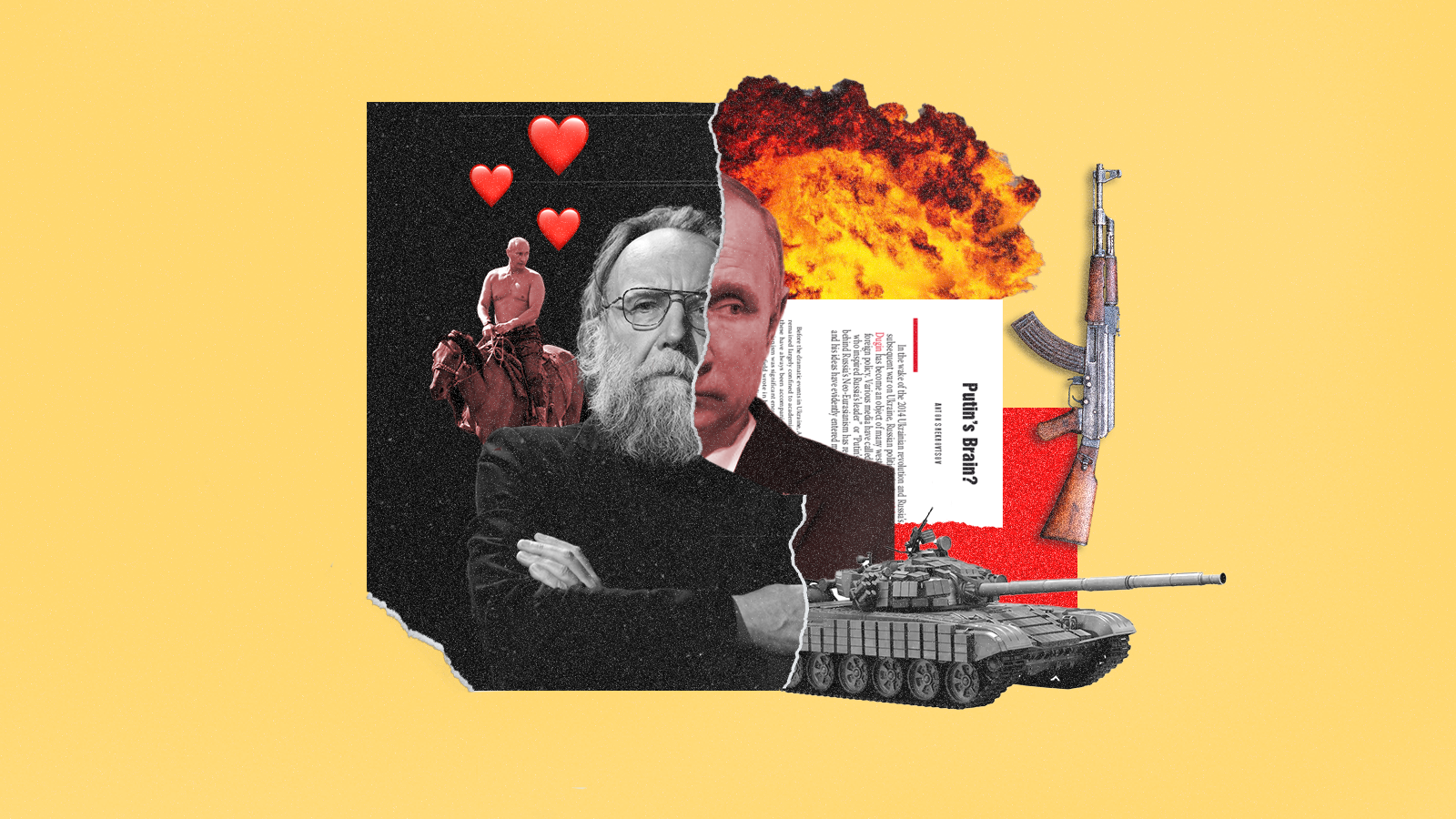

Independent polls estimate that around 75% of Russians support the war against Ukraine: Putin’s propaganda machine has its own faces that ceaselessly spout words in line with the ideology justifying everything the Russian forces have been committing against Ukrainians for more than a year. One of them is Aleksandr Dugin, whose character has been fueling speculation: it is unclear whether he ever had a true role in shaping Putin’s ideas and actions or is just a self-proclaimed prophet who put himself on a pedestal and who shall not be taken too seriously.

Brittany Pheiffer Noble, Ph.D., gave a lecture at the Danube Institute in Budapest about the extremely controversial philosopher Aleksander Dugin, the people revolving around him, and his belief system concerning the Russian people. Brittany Pheiffer Noble is an expert on 20th-century Russian history, and she focused on the essence of Dugin’s ideology, Eurasianism (евразийство), while discussing the prophet’s current role.

She started her presentation by asking the big question: what does Vladimir Putin think? Many people are looking for the answers every day, but it is virtually certain that we will never get a comprehensive and completely satisfactory explanation. Putin’s motives and character are largely shrouded in mystery, and one of the West’s speculations suggests that the Russian President’s thoughts and, consequently, decisions are highly influenced by the infamous activist-philosopher Alexander Dugin. The philosopher was already mentioned in the Western media during the annexation of Crimea in 2014, and Dugin’s ideology, Eurasianism, is a dominant shaper of the Russian soul, capable of portraying the legitimacy of the war in Ukraine in a very different light for Russians.

Understanding Aleksander Dugin’s character is challenging, and we must start the analysis with his creed, Eurasianism. This belief system emerged in the 1920s and is tied to Russian emigrants who published several essays abroad during this period, creating a new Russian identity based on Eurasian principles. Eurasianists approached all questions of history, culture, politics, and religion with the conviction that the territory of Eurasia shall be a single geographical and cultural entity by nature. Thus, they advocated the political unity of the continental area, bringing a new twist to the issue of Russians’ belonging. Eurasianists classify Russia neither as European nor Asian; they put the country on a „third way.” The Eurasianist movement provided the most structured answer to the issue of post-revolutionary Russian identity. Eurasianism aimed to create harmony between the different peoples of the continental area, which is a seemingly harmless intention. Still, this belief system also provided grounds for hostile, paranoid views.

Dugin’s ideology is called neo-Eurasianism, and the philosopher’s personality is surrounded by many theories and ambiguities. He is not only an enthusiastic political activist, but has also been involved in youth movements, taught philosophy in institutional and informal settings, and was an early predictor of the Internet’s potential to spread political ideologies. In fact, his belief system is based on the fight against Americans and the Atlanticist hegemony, promoting a multipolar geopolitical order that rejects liberalism. Dugin actively promotes the ideology of Eurasianism since the early 2000s, linking it to the incessant threat of American imperialism and NATO. Dugin later also started to spread that the Americans had created an artificial civilization. According to the tenets of Eurasianism, becoming European as a Russian is an unnatural process since Russians cannot adapt to the Western establishment, and as Dugin’s ideology evolved, it gradually became a completely anti-imperialist and anti-modernist belief system. Dugin rejects progression and claims that the development of Eurasianism is not progressive but cyclical. He sees the West and the Western values as the opposite pole, meaning ultra-individualism and superficial freedom, and advocates social responsibility and spiritual freedom instead, defining these terms in his own way. Nonetheless, paradoxically, he equated the turn towards Eurasianism with the turn towards modernity and the rejection of his ideology with the rejection of modernity.

Brittany Pheiffer Noble stated that Aleksander Dugin is „a bigger Putinist than Putin himself:” he is a fervent supporter of Vladimir Putin, but the extent of his influence on Russia’s present and the Putin regime is uncertain. He undoubtedly backs Putin, but it is questionable whether he has any impact on the Russian political scene. Some people believe Dugin is indeed „Putin’s brain,” and the philosopher seemingly likes to be depicted in this role. Still, no concrete evidence of such strong influence has ever been seen.

Dugin is an outspoken advocate of aggression and violence and has long been a supporter of the annexation of eastern Ukraine by Russia. In 2014, during the occupation of Crimea, he advocated for the „murder of Ukrainians” and was expelled from several academic institutions because of his extremely barbaric and unacceptable ideas. Therefore, it is unsurprising that he fully supports the invasion of Ukraine and justifies his overtly inflammatory attitude with the violence of the United States and NATO. Dugin expresses the terrifying, hateful, and extremely destructive ideas that many people in Putin’s Russia agree with but would not necessarily embrace openly. However, his importance should not be over-emphasized, as his goal with his outright provocative attitude is probably exactly that: getting much attention from the West. Understandably, his figure of a self-proclaimed prophet, a West-hating philosopher, and an ultranationalist activist vehemently supporting the dictatorial Russian leader seems significant from a Western perspective. Still, maybe his acts are only mere self-serving and loud performances.

Graphics by Roland Molnár

Demas Nwoko receives the Lifetime Achievement of the 2023 Venice Biennale of Architecture