The book How to Feed A Dictator, which has now been published in Hungarian, features the chefs of five famous 20th-century dictators (Saddam Hussein, Idi Amin, Enver Hoxha, Fidel Castro, and Pol Pot). What do the chefs of dictators from distant countries have in common? How was self-criticism practiced in communist Albania? What is the reason for the nostalgia for dictatorships? Which dictator’s chef would the author of the book be? We asked Witold Szabłowski, the Polish writer of How to Feed A Dictator.

How do you work, and what does your daily routine look like?

Well, recently everything has changed because of the war. I got refugees at my place, I was volunteering in a couple of pro-Ukrainian projects, and now I’m curating three festivals about Ukrainian culture and literature. Half of my last Polish book is about Ukraine. Like How to Feed A Dictator, it is also about chefs, about how Russia is using the kitchen, chefs, and recipes to build its empire. It starts with the chef of the last Tsar and ends with that of Putin. I wrote this book three years ago, back then it was possible to meet Putin’s personal chef. Now I think they would put me in prison for something like this. So now the situation is totally different from the norm, but for How to Feed A Dictator, which has just got published in Hungarian, it took me four years to collect the material. I must say, the biggest challenge and the thing that consumed most of my time was hunting down the chefs.

How did you find them?

I wanted to spend a week or two with the chefs and cook with them. It was a challenge to make these guys speak, to gain their trust, and especially to make them let you into the kitchen because that is their kingdom. The kitchen is a private, intimate place, it’s where the heart of every chef lies. So if a chef lets you into their kitchen, it means they really take you as a friend. The easiest to find was the chef of Fidel Castro as he runs a little restaurant in the middle of Havana. I simply went to the city center with a bottle of very good Polish brandy and I was just trying to be friendly, trying to make a good impression. The toughest was with the chef of Saddam Hussein, who didn’t want to be found. The last thing he wanted was that some weird guy from Poland would visit him and ask him questions about his work with Saddam. Local fixers, local journalists, and activists helped me everywhere.

In your book, there is one dictator from every continent. Was this a conscious decision?

Yes. I thought of it as a very ambitious project and I did not want this to be a culinary book, although it is, of course, at a certain level, because you have the recipes, you have the chef stories, etc. But from another aspect, it’s the culinary and political map of the changing world in the 20th and 21st centuries. It includes the post-colonialism in Africa, the revolutionary movements in Asia and Latin America, and at the end, the 21st century with the fall of Saddam Hussein. And why isn’t Stalin or Hitler in it? My condition was to meet the chef in person. I thought of it as an extra value that I’m not writing from archives, I’m not rewriting other books, but that I meet all these people.

Have you met the chefs of other dictators as well?

Yes, I met those who cooked for Tito, Kim Jong-il, Muammar Gaddafi, and Nicolae Ceaușescu, but I had to find a moment when I just say stop. I didn’t want the book to be a collection of every chef of a dictator whose hand I shook. I think the five dictators I chose were significant in the time they lived.

The European dictator is the Albanian Enver Hoxha. Why did you choose him from our continent?

Hoxha is probably not very well known, as he is from Albania. But for me, he was incredibly interesting because in Albania communism was at its extreme. He totally isolated the country. At the beginning of the chapter Mr. K., as I call the chef, tells the story of the self-criticism sessions. It is so touching, because he says, “Listen, I didn’t do anything wrong, but anyway, we had to start every day with the self-criticism sessions because otherwise we would be punished.” A good communist is always trying to find a reason for self-criticism. Just imagine that every day you start your work with thirty minutes of self-criticism.

You did a lot of research, read books, and had meetings with historians. Still, how could you be sure that the chefs were telling the truth?

I spent a lot of time fact-checking, because there were no sources to confirm the things that they told me. If somebody tells you about some little habits of a dictator, there are not too many people who can confirm that. So I always tried to find other people that worked or lived with these dictators. For example, I met a personal doctor of Saddam Hussein, and I confronted him with the chef’s words. I also met two sons of Idi Amin just to confirm what the chef told me.

In spite of the different cultural backgrounds and cuisines, did you find anything in common in these chefs?

I was really surprised that they were all very similar characters. So they were all extroverts, open-minded, friendly, and easy to talk with. They were all people I felt good with. In the beginning, I thought, maybe it was a coincidence, but then I met over seven chefs of dictators, and they were all great company. And then I understood that dictators are not only perfect manipulators but also very good at psychology, they have a natural instinct to understand people. They understand that you can be at war with everyone, with your wife, with your prime minister, with other countries, but not with your chef. Because if a chef is in a good mood, you will feel that in the meals he prepares. On the other hand, if you tease your chef, you will probably get sick. This is why they always hired very reliable people as chefs, people who made them feel good. All these chefs I met were spreading good energy. Then you think about who they were cooking for: mass murderers, dictators, autocrats. It makes you feel awkward, but this is how it was. I loved spending time with them.

You have a book titled Dancing Bears. True Stories about Longing for the Old Days, in which you write about people who are nostalgic for dictatorships. In How to Feed A Dictator you also met such people. What could be fueling this nostalgia?

Freedom—and this is what the Dancing Bears book is about―is not easy. Dictators take away your freedom, but they give you the feeling of stability in return. Unstable times are usually the best moments for dictators. I think dictators play a lot with our fears, they always pretend that they know how to solve our problems, and they generally lie. In How to Feed A Dictator, the Iraqi taxi driver doesn’t remember that people were killed in Saddam’s regime, but that there were no gangs in Baghdad. Of course, there were no gangs because Saddam’s government was one big gang and it didn’t allow other gangs to prevail. I think this is where the nostalgia comes from.

You interviewed two of Fidel’s chefs (Erasmo and Flores). The text of Flores reminded me of a Hrabal novel, especially the book I Served the King of England. Have you also read literature to make the book?

When I want to make my writing a bit more literary, I just choose which style I would like it to be written in, and in that chapter, I took Hrabal as an example, so thank you. I also read Joseph Heller and Kurt Vonnegut. Even when I write about very tough things, I want it to be ironic, to have some humor or some light, I would say. I didn’t want to sink into the tragedies, which could have been easy with people like Saddam and Pol Pot. I wanted to leave some hope. And for me, the mentioned writers are the ones who give hope.

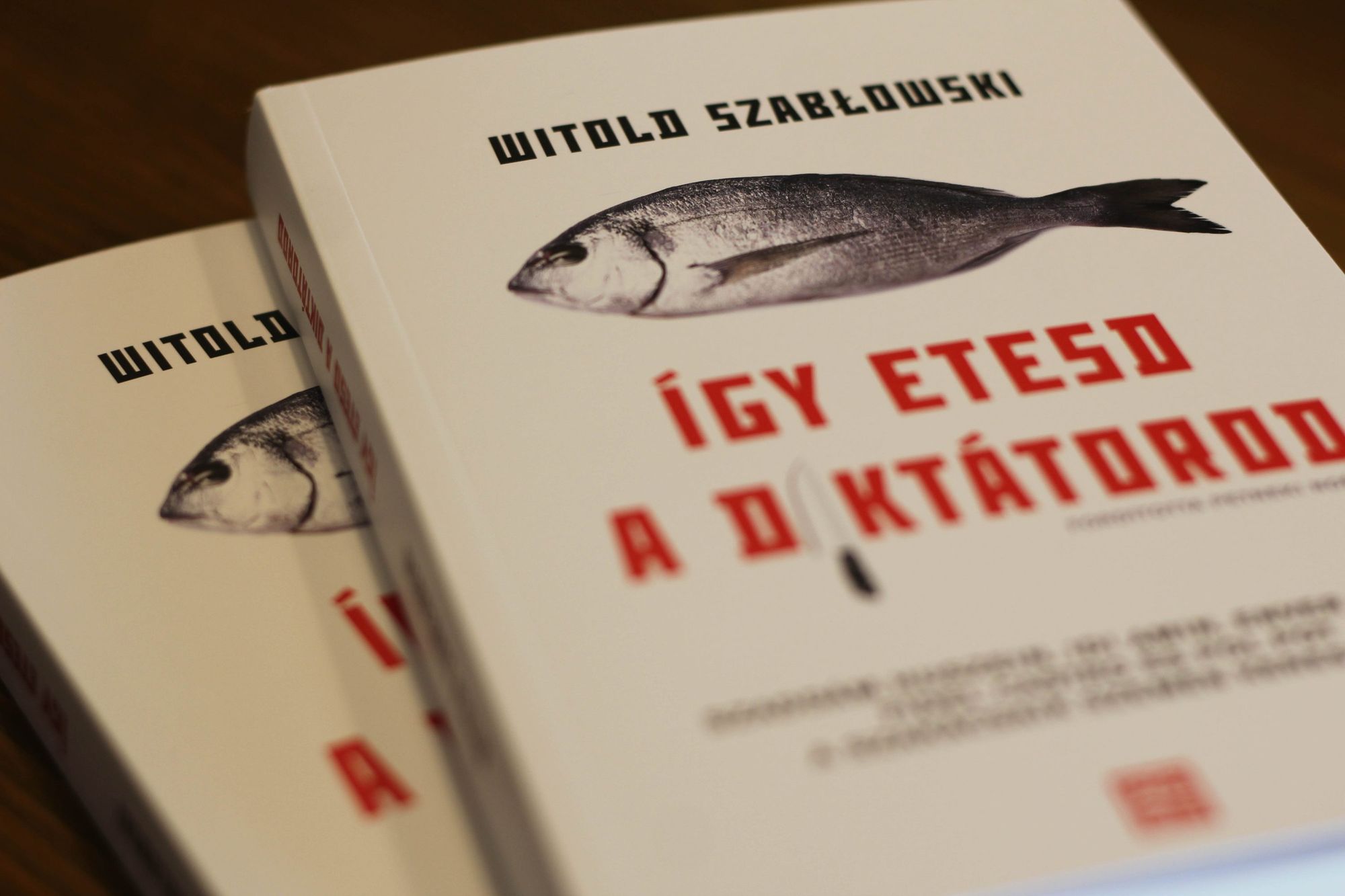

I saw the covers of the English, German, and Polish editions of How to Feed A Dictator. Each of them approached the topic with different visual solutions. Do you take part in designing your books?

I try to participate in this process in Poland, I work with the graphics. But I have so many books in other countries right now, I don’t have time for this. I just get the covers for acceptance, and I usually accept them.

If you had to choose, which dictator’s chef would you be?

Fidel Castro. He wasn’t that bad compared to the other dictators and I think he was an exciting guy to be with. He was always doing something interesting, he was a bit psycho, sometimes in a bad, but sometimes in a good way. In his case, I can believe that he had good intentions, but things just went wrong. And I like his style of drinking good whiskey or rum, smoking cigars, and fishing with Ernest Hemingway. Flores said that he met Gabriel García Márquez many times, he was cooking for those two in private dinners. So I mean what could be better than that? Cooking for Fidel and Marquez and listening through the little hole in your door to what they are talking about. That would be great.

Witold Szabłowski: How to Feed A Dictator

Hungarian Translation: Noémi Petneki

Prae Publishing, 2022

Many thanks to Prae Publishing and PesText Festival for the interview opportunity.

Cover photo: Mariia Kashtanova, Prae Publishing

Lithuanian women and sustainable fashion—we quickly took The Knotty Ones into our hearts

Next IHF Men’s World Championship ball unveiled