The ZEGZUG project is more than just an architectural initiative—it represents a complex shift in how we create and think about space, where psychology, sustainability, and community building intersect. Founder Boldizsár Partos envisions human-centered spaces that not only meet the needs of the present but also act as bridges across generations and social groups. In this interview, he speaks about rural roots, digital content creation, inspiring architects, and how buildings can become truly supportive living environments.

What inspired you to start the ZEGZUG project?

The built environment is more than a collection of physical spaces—it directly impacts our mental, physical, and emotional well-being. The psychological aspect of the project came into focus through my brother, Bence Partos, who is the founder and owner of Mindset Psychology. We created ZEGZUG with his extensive support. Our vision was rooted in the belief that the architecture of the future must be health-oriented, human-friendly, and sustainable. Through ZEGZUG, we aim to address the alienating scars left behind by socialist urban planning, and instead create spaces that foster connection across a wide range of people.

What values or approach do you want to communicate through your work?

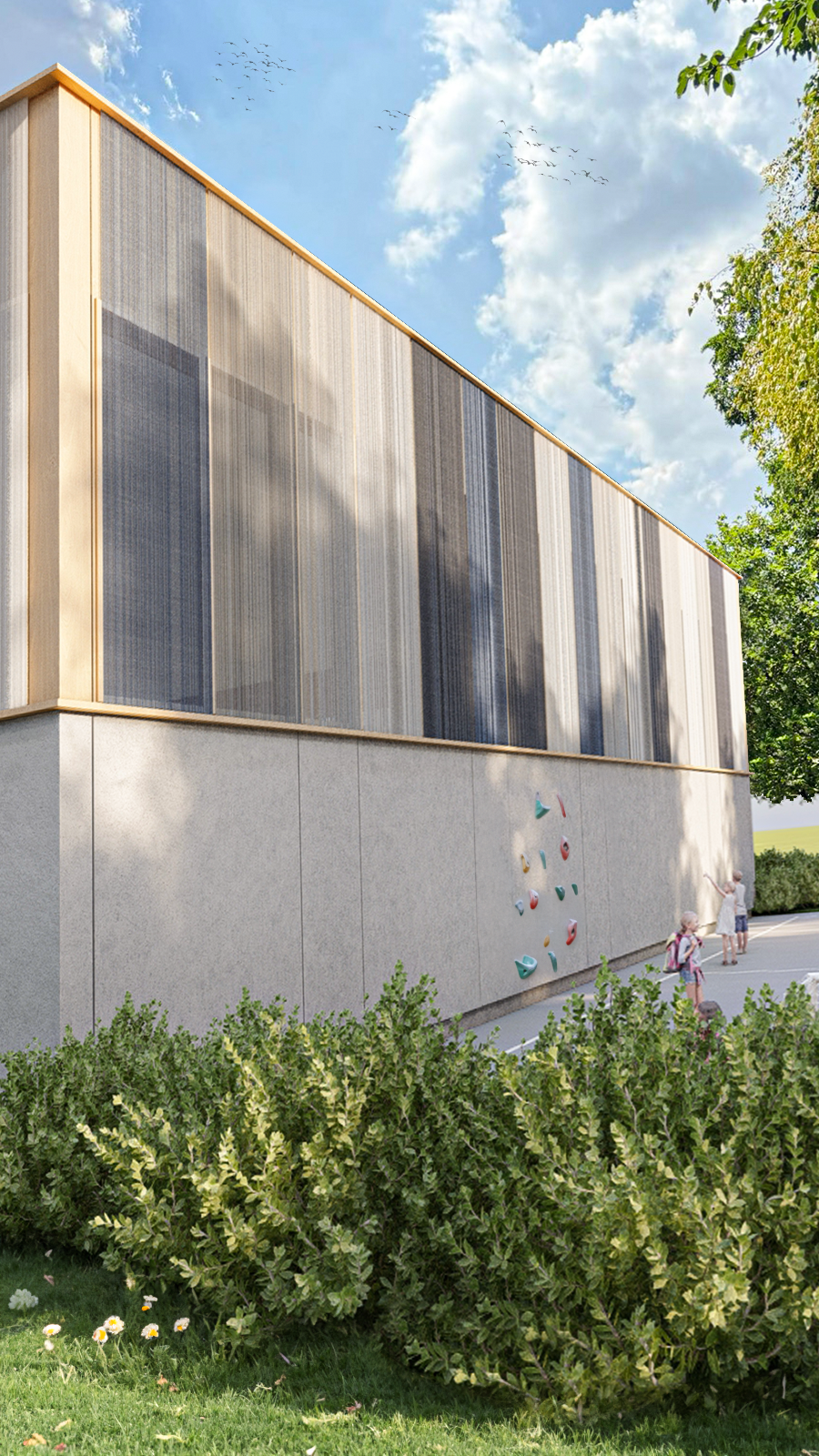

We approach the quality of the built environment through multiple disciplines: engineering, art, and psychology. Our aim is to create spaces that offer more than just physical shelter—they carry meaning and value beyond their material existence. We believe architecture should serve the diverse needs of people. That’s why our spatial concepts go beyond the physical: instead of simply building houses, we create homes; instead of isolated structures, we design community spaces; and instead of just buildings, we envision supportive environments. We also make use of digital simulations to optimize natural light and ventilation in our buildings.

How did your hometown or the first architectural spaces that impacted you shape your own architectural perspective?

I spent the first ten years of my life in a small village in Borsod County. The closeness to nature, the tranquility, and the strong sense of rural community continue to influence how I think about built environments. The functional simplicity of vernacular architecture still informs our architectural attitude, now combined with contemporary innovations.

How do you reconcile the fast pace of digital content creation with the slow, often years-long process of architectural thinking?

Adaptability in architecture can be a tricky concept. Often, a solution must be highly specific to its location and context, and therefore cannot be directly replicated. Many of today’s trendy prefab homes and "house factories" fall into this trap. But we believe that architecture can be adapted—not in its physical form, but in its underlying ideas and values. That’s what we aim to convey in our fast-paced TikTok videos: we distill the core concepts of a complex, long-term project into ideas that others can meaningfully adapt to their own context.

How do you see ZEGZUG’s role in architectural education, particularly for younger generations?

ZEGZUG addresses contemporary topics in a way that connects across professional boundaries and generations. We often tackle highly technical subjects but present them in an accessible and engaging format that anyone can understand, regardless of age or field. Through this, we aim to inspire more conscious awareness of our built environment.

Is there a particular architectural movement or thinker who has had a major impact on you, professionally or personally?

Diébédo Francis Kéré, who was born in Burkina Faso, has had a significant influence on me. His work centers on reinterpreting local materials and building techniques in a contemporary way—something highly relevant in Hungary as well, especially in terms of rediscovering sustainable materials like rammed earth. His bioclimatic approach and community-driven architecture inspire me to create spaces that are sustainable and human-centered, always grounded in local context. Overall, Kéré’s work encourages me to see architecture not merely as an aesthetic pursuit but as a tool for serving both communities and the environment—and for initiating positive social change.

What does sustainable architecture mean to you personally, and how is it reflected in the project?

Quite simply, it means designing buildings, spaces, and cities that meet today’s needs without taking away the ability of future generations to meet theirs. We also place strong emphasis on making sustainability widely accessible—not just for the few.

If you could make one major change in Hungary’s built environment—whether at an urban or residential scale—what would it be, and why?

As an architect, I would focus on strengthening the community-building functions of apartment buildings, rental housing, and urban public institutions. These spaces should be designed based on the needs of their users, not driven by profit. Designing with community in mind is a societal issue—it can even contribute to longer, healthier lives.

What does the future hold for ZEGZUG? Are you planning to explore new platforms, formats, or collaborations?

We’re working on introducing the concept of “happy efficiency” into industrial and office architecture. By closely integrating architecture with environmental psychology, we aim to create supportive physical environments. Through the strategic use and monitoring of natural light and ventilation, we can design more efficient, cost-effective, and comfortable buildings. With the fusion of psychology and architecture, we can tailor spaces to specific patterns of human behavior. In the future, we hope buildings will be seen not just as functional physical structures, but as meaningful connections that link function with soul.