Apartments that can be expanded into a suite, room service, hotel bars, exotic fruits and currencies worth a fortune—a few decades ago, on our side of the Iron Curtain, these used to be the words that summoned hotel guests looking for something exciting and unfamiliar. Hotels, motels and inns established to boost tourism during the socialist era still fascinate guests with their unique and peculiar aesthetics given that you can find the rare gems of lodgings that successfully preserved the past era’s illusive luxury for the 21st century.

This article originally appeared in issue no. 4 of the Hype&Hyper print magazine.

The question in the title is supposed to be a little provocative, dare we say, poetic as our unanimous answer would definitely be “yes”. The simple, yet charming aesthetics of the ‘60s, ‘70s and ‘80s is once again having a renaissance moment, especially in interior design—we all know retro never goes out of style. However, declining the offer in the title is entirely acceptable—there aren’t many survivors of socialist hotels that were able to conserve its authenticity. Most of these establishments were demolished or fell victim to time and neglect or they befell an understandable, yet even worse fate: the establishments that were thought to be outdated were refurbished according to the requirements of modernity.

When it comes to trends, nowadays, booking accommodation is easier than ever, however, during travels, people are looking for a unique experience that far exceeds the comfort levels signaled by the amount of stars a hotel has. A few years ago, fuelled by the popularity of the TV series Chernobyl, a couple from Vilnius remodeled the flat in a panel building that used to be one of their grandma’s to great success. The users of Airbnb loved the Soviet atmosphere they saw in the blockbuster even though the accommodation came without continental breakfast or spa services. A fantastic example of socialist hotels is PURO Hotel in Kraków. We extensively covered the establishment that was translated to the modern era by Piotr Paradowski Interior Design Studio and proved to everyone that legacies built a few decades ago are worth saving especially when the new design oozes creative, innovative energies.

Not nearly as fascinating, the iconic Interhotel Moskva in Zlín, Czechia is still worth mentioning. We had the opportunity to personally experience the hotel during Zlín Design Week when we visited this wonderful city with a rich industrial heritage. Choosing Interhotel Moskva was a coincidence, but when a friend of ours who works as an architect mentioned the building’s history, we were intrigued. The construction based on the design of Miroslav Lorenc started in 1931. The 11-floor hotel was ordered by a famous local, Tomáš Baťa. The modernist building was initially destined to be used as social housing, only after a while, with Vladimir Karfik’s mediation could the establishment become a hotel offering western comfort in 1948, and re-baptized as Hotel Moskva. The hotel, situated just across the street from the famous shoe factory, welcomed guests traveling from the West as well as envoys arriving from other socialist states with 300 luxurious rooms. Even though we cannot say our stay at the Interhotel was a perfect experience of traveling back in time, while having breakfast, we had the opportunity to marvel at the bar left from the ‘70s-’80s and the upholstered, metal bar stools fastened to the floor.

Socialist hotels also enchanted travel writer Mark Baker living in the Czech capital: he spent several nights in the Intercontinental Hotel in Prague during the ‘80s, followed by thorough research into the establishment’s history, and he went on to explore the Eastern Bloc’s other hotels as well. In his blog post titled You Can Check Out Any Time You Like…he chronicles the history of hotel construction in the era and lists features that were specific to buildings built on our side of the Iron Curtain from the Czech Republic all the way to Moldova. “It may not be obvious now, but if you happened to be traveling through any city of any size in Central and Eastern Europe before 1989 and looking for some action—and by this I mean a meal, some drinks, and maybe a bar or a club—chances are the only place in town you’d find would be at the city’s central, state-run hotel”—Baker writes. The names of the hotels in the region were also peculiar. Aligning with current political ideologies, the accommodations frequently received names like “Freedom”, “Peace” or “Youth”. In Hungary, the hotel designed by István Zilahy in 1964 and situated close to the Eastern Railway station is called Freedom Inn or the accommodation constructed according to the designs of András Csángó also in 1964 for the guests of different youth movements named Youth Inn are telling examples of this trend of the era.

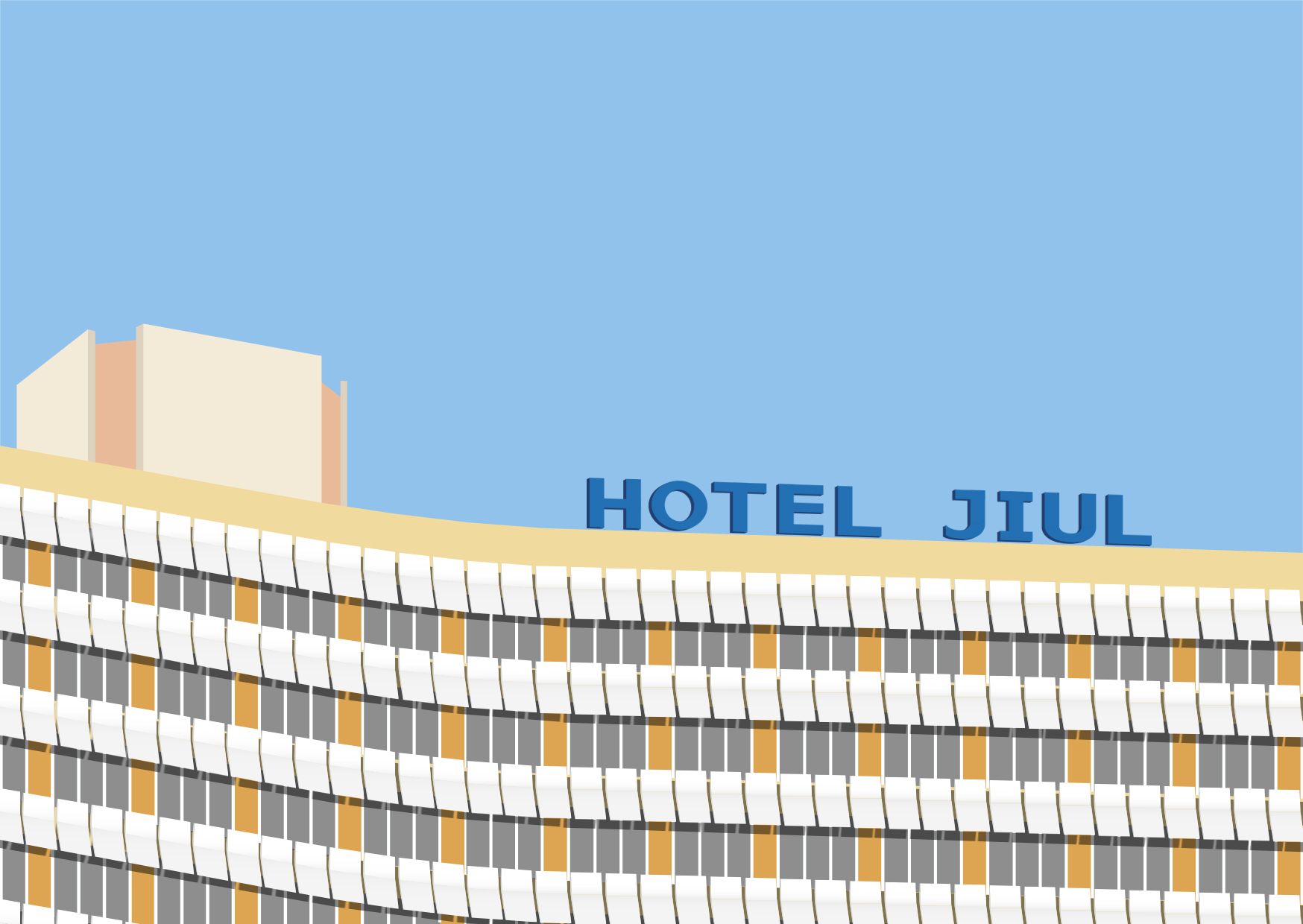

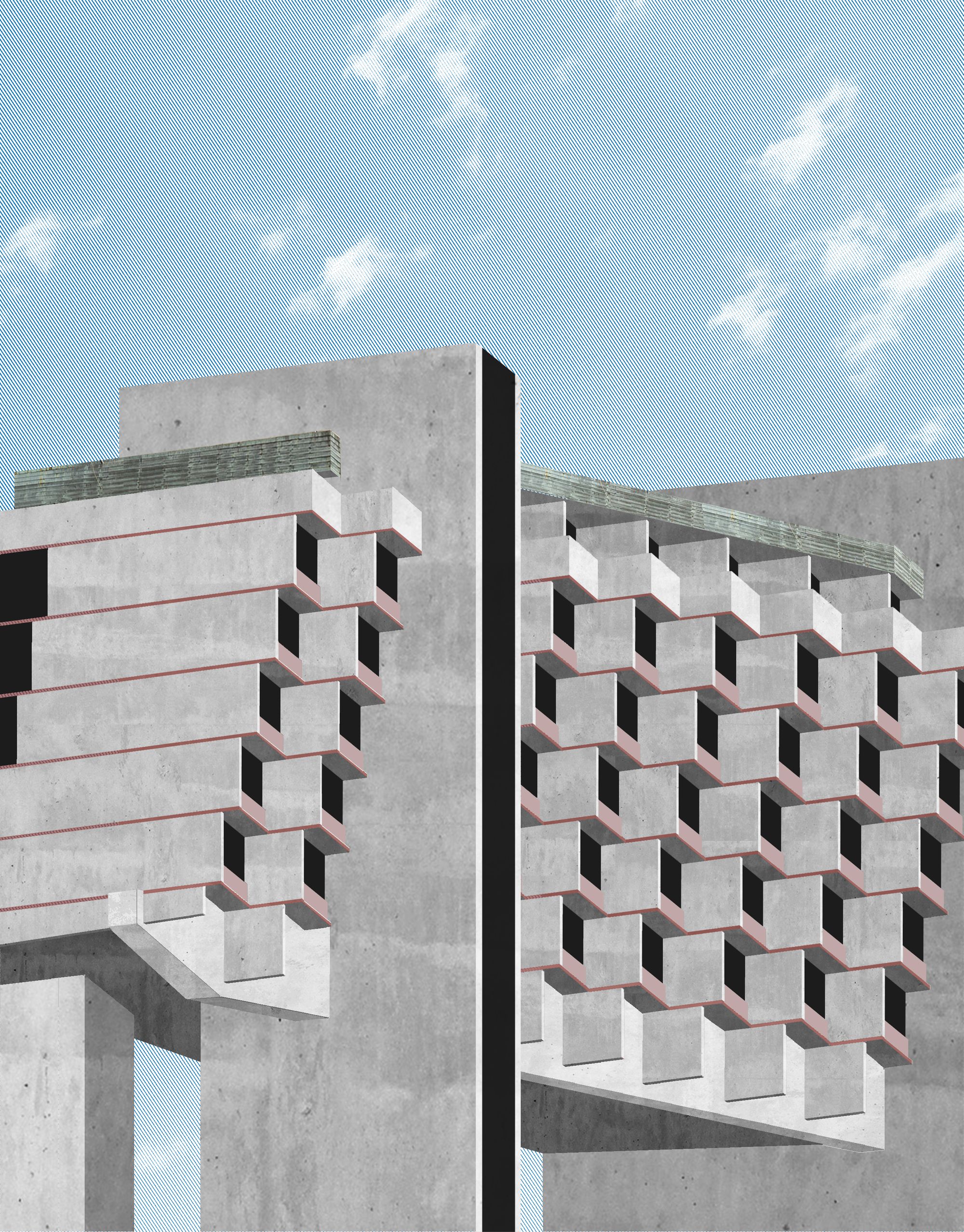

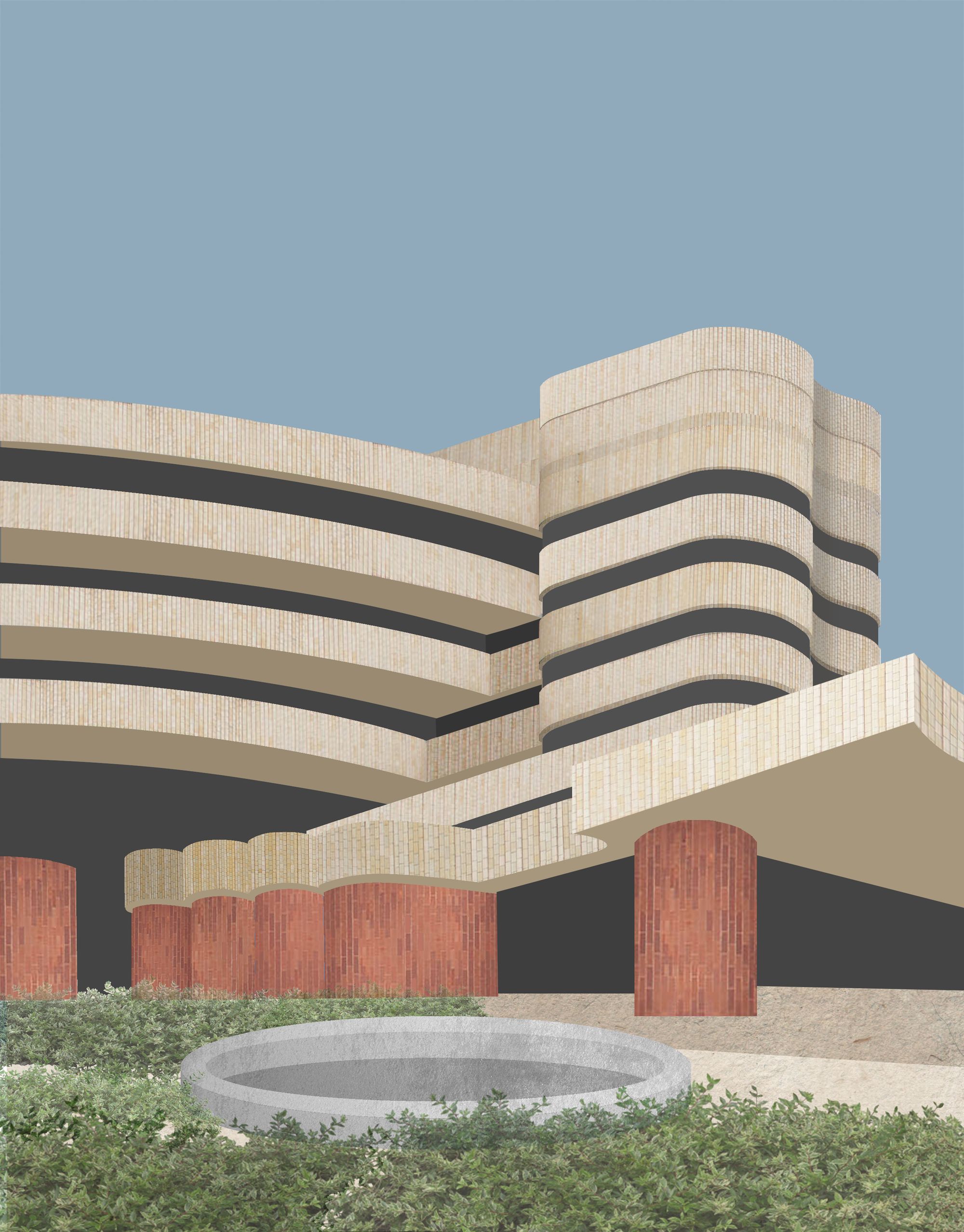

Baker’s blog post is a real treat for those who are looking for a way to travel back in time: you can read about the infamous Hotel Jiul in Craiova, Romania that was said to be the cheapest and scariest accommodation option at the time. Unfortunately, after its closure in 2015, the Ramada Inn hotel chain changed the building entirely and rendered it unrecognizable. According to the photos taken in the ‘70s, Mark claims even David Lynch would have been glad to spend a night in a room with walls painted blue and beds covered with deep blue velvet bedspreads in Hotel Jiul. Hotel Forum in Kraków is the crown jewel of brutalist architecture, according to Baker. Fate was a bit kinder to the hotel located on the shore of the Vistula as a few years ago, Forum Przestrzenie café and cultural space opened on its ground floor bringing a lively cultural scene to the establishment. Hotel Praha was known for its distinctive, wave-like, dynamic facade. The former hotel housed 136 rooms each with a private balcony and is said to have welcomed Leonid Brezhnev, and even Tom Cruise among its guests. Sadly, the building was demolished in 2014.

Unfortunately, we can’t take you on a real time travel journey, but we hope that Boróka Felső’s illustrations evoke the uniquely distinctive atmosphere of this era of the past.

Illustration by Boróka Felső | Instagram

Budapest Mosaic | Urban tales from Luca Patkós

Romania and Bulgaria are trying to convince the skeptics of their Schengen accession