Animism has been present in human life since eternity, often referred to as the most primitive belief system, a kind of spiritual fad. Despite the negative overtones and general denial, it also permeates our relationship with our objects and electronic devices, even if it is not, in most cases, consciously acknowledged or called by its name.

The term animism comes from the Latin word anima, meaning soul, and refers to the belief that not only humans but also inanimate entities have souls. In our latest Hype Lab episode, linked to our thematic month focusing on objects, we explore contemporary manifestations and influences of animism.

We don’t hear of many people who openly declare themselves animists nowadays, while our actions often disprove this. Addiction to smartphones, intimacy with our cars, attachment to souvenirs from travels, or gifts from people dear to our hearts, to name just a few examples. Along with this, our relationship with our objects is ambivalent in nature: while these favorite pieces are truly emotionally charged and cherished to the extreme, others are ruthlessly discarded and replaced. Our society is, on the one hand, obsessively anti-animistic, while two striking trends are flourishing: techno-animism and a return to the sanctity of craftsmanship.

Technoanimism

The essence of animism can also be interpreted as a kind of early network thinking, where the elements of our world are not subordinated to humans, but participate in the system as equal players. It is no coincidence that modern man has fought it tooth and nail to prove his own superiority. However, the age of awakening technology and the Internet of Things has once again questioned human-centricity. “Local, instrumental manifestations of complex socio-technical systems, such as digital home assistants, chatbots or smartphones, also give rise to a new type of animism, in which the spirit world invades the technological environment. Inanimate objects and networks that transcend the human scale are given a familiar, human character,” shared, Ákos Schneider, design theorist.

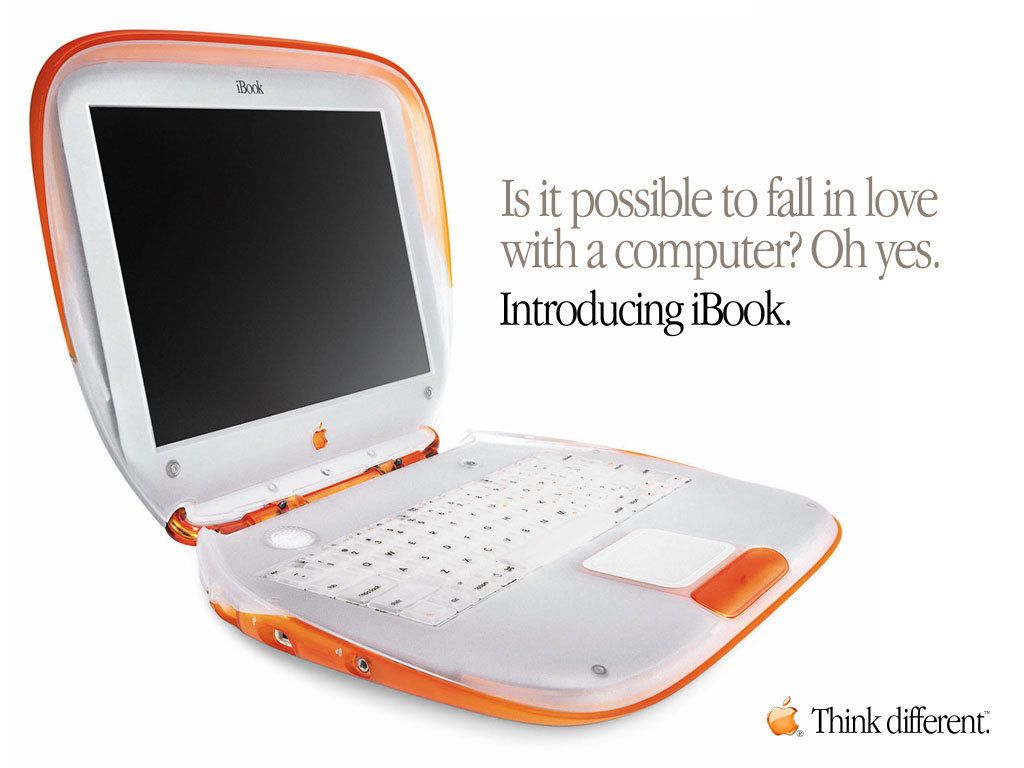

Apple, for example, advertised its first Ibook with a techno-animated slogan back in 1999 and deliberately gave it a friendly and likeable look. As we discussed in a previous Hypelab article, designers are increasingly humanizing technology, and we are increasingly behaving as if our gadgets were truly alive: we talk to them, ask for their opinions, and they listen, respond and influence us. This kind of techno-animism, or new animism, can help technology to become more easily accepted and naturalized in society while at the same time raising concerns. In the case of neo-animism, it is therefore not the animistic belief itself that matters (that is, whether we really believe that our laptop has a soul) but the behaviours that occur as a consequence of our interaction with intelligent objects.

Animism and sustainability

The more objects multiply, the more our culture pretends that they are dead: we no longer replace them only when they become useless; we don’t even try to save them. The consumer society, and the constant pursuit of novelty without emotional engagement (think of fast fashion, for example), is essentially the embodiment of anti-animalism. And from this perspective, reviving animism can contribute to sustainability efforts. Jonathan Chapman, a researcher of emotionally durable design, sees the solution to the problem in the affective sustainability of objects, for example, when the object itself elicits sustainable behaviour from its user. One of the greatest strengths of affective sustainability is its focus on positive emotions. It’s not about eco-anxiety and resignations, but about valuing what we have. So alongside recycling and circular design practices, a contemporary animist approach can be a way to better appreciate and connect with what we have in the long term.

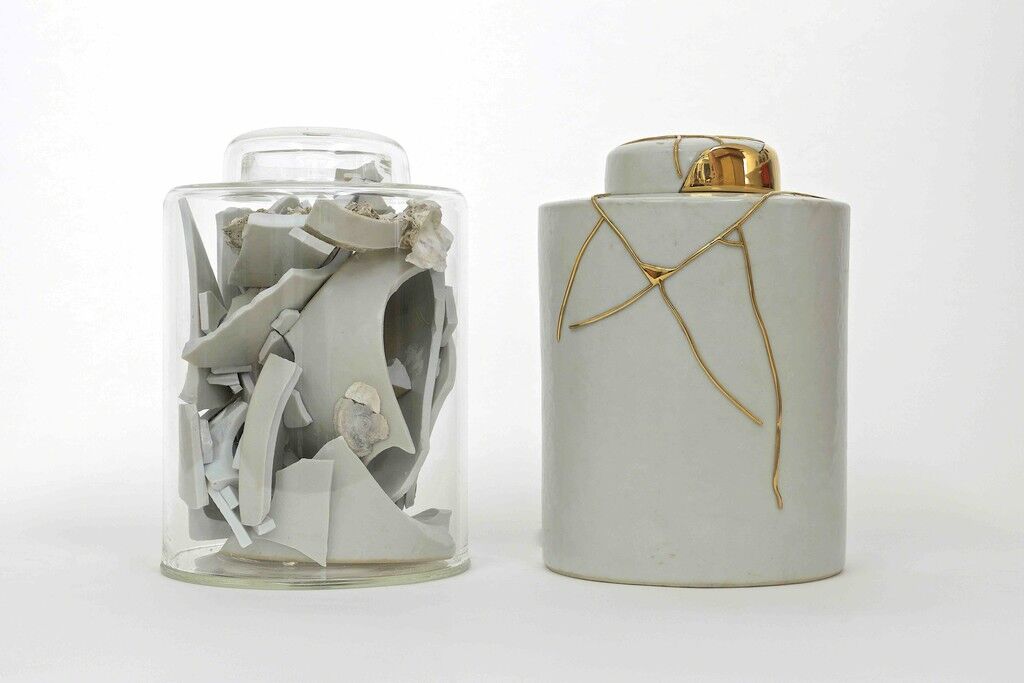

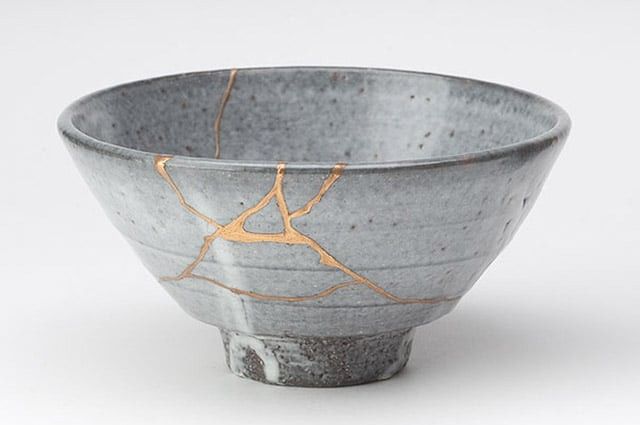

One practical application of this interpretation is the art of repairing objects. Four to five hundred years ago, kintsugi, or gold engraving, was developed in Japan as a technique for repairing broken ceramics. Objects are thus valorized and given a new layer of meaning rather than being discarded. This method also serves as an inspiration for contemporary artists, with Korean artist Yeesookyung creating stunning waving sculptures and British artist Paul Scott collaging various found ceramic pieces. It is also linked to the Repair movement, which we recently reported on in the context of Joanna van der Zanden’s initiative.

It is interesting to observe, however, that the neo-animistic tendency does not necessarily result in a longer relationship with our objects: we become attached to our electronic devices not for their own sake, but for what the technology they contain enables. Our cherished phones will soon be replaced by a newer and smarter model, and the old one can go in the trash. From this point of view, the two trends have an opposite effect on the lifespan of our object culture.

Animist designers

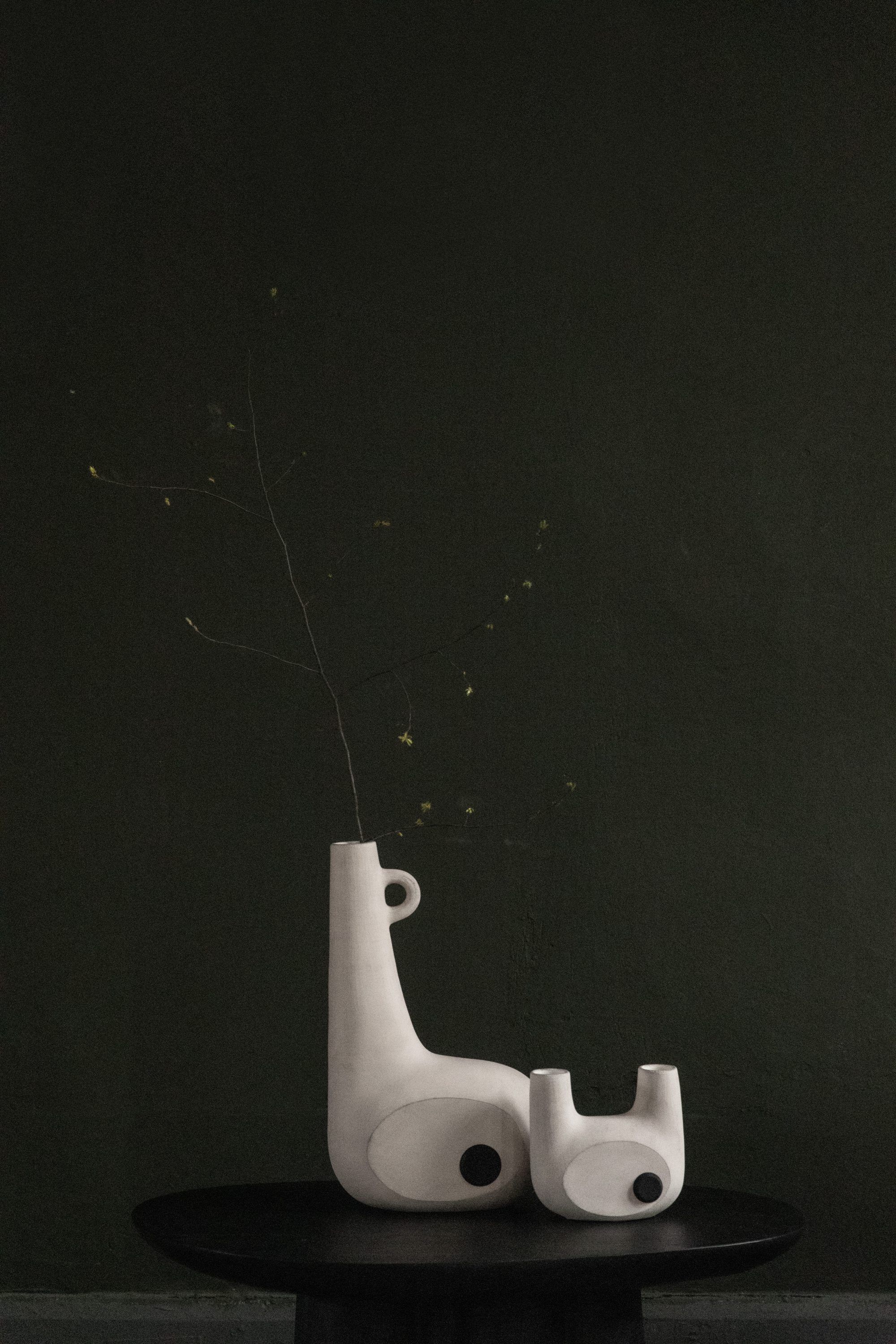

Although the examples above have clear animist features, they do not use this specific term. So, we interviewed two design studios that consciously base their brand image on contemporary animism. Ukrainian Faina, for example, sees the importance of animism in returning to craftsmanship and keeping local traditions alive and tries to focus communication on spirituality.

“Following the animistic approach will help us to revive a primal connection with the living world. I believe in today’s world of mass culture, we need to rethink our relations with the surroundings—to buy and produce less and search for the soul. With all the technologies and abundance, the modern world offers, we become more shut-in, distracted from the essential and important. When surrounding ourselves with soulless objects, we slowly unlearn how to feel. In a modern context, animism is about more conscious, deep relations with objects. When you choose what truly belongs to you. Not what’s popular on your Instagram feed,” Victoria Yakushka, the founder of Faina, told us.

“In my view, all craft objects have a soul, vibrant energy that you feel while interacting with them. It happens because you feel that strength, an emotion that another person has put into it. We collaborate with local artisans all over Ukraine and craft each object by hand in very limited editions. I believe it’s our way to preserve the unique spirit of the object,” Victoria added.

The Rotterdam-based design duo Supertoys has a different understanding of the essence of animism, more in line with the techno-animist approach. “The understanding of animism is mostly reduced to the belief that objects have a soul, but that’s not how we relate to animism at all. For us, it is not about any kind of belief system. Instead, like many indigenous tribes, we like to relate to the “bigger whole” and understand ourselves as a small part of an infinite network of beings, humans, animals, plants and objects, where there is no distinction between subject and object, nature and culture. The relation between humans and their furniture, for example, is in itself an entity, an agency on its own. We approach furniture as communicative subjects rather than the inactive objects perceived by modernists. So, in that way, it is quite the opposite of a minimalistic lifestyle where you strive to only use things that serve a function. For us, the purpose of an object is not a question we ask ourselves since the question in itself implies a hierarchical relationship and would in itself obliterate any emotional bond between humans and objects. If an object communicates only ‘function’ or a sort of minimalistic ‘usability’ it will only serve as an extension of the human body or mind, which creates an unhealthy relationship in our view,” the two designers, Merle Flügge and Job Mouwen told us. Therefore, with their furniture, they want to explore the ambiguity of objects. An example of this is the Cosmic Flower table, where the designers asked the philosophical question: what if the table really wanted to be a flower? This approach to design allows them to think about things as a whole, in contrast to an anthropocentric view of the world.

/Photo: Pim Top/

To put it all together, animism is about rethinking our relationship to the world, the boundaries between human and non-human, living and non-living. Meanwhile, the traditional trend and techno-animism have opposing effects in many ways: while the former encourages connections, the latter can be alienating, the former prolongs the life of objects, the latter encourages their regular replacement. The subject is far from clear-cut and can sometimes go in the direction of wackiness, but it is undoubtedly more complex than to sweep it aside as a mere spiritual fad.

Mama’s cooking, in Chinese | Authentic lunch at ZHU & Co.

Preserving history: progressive monastery renovation in Corsica