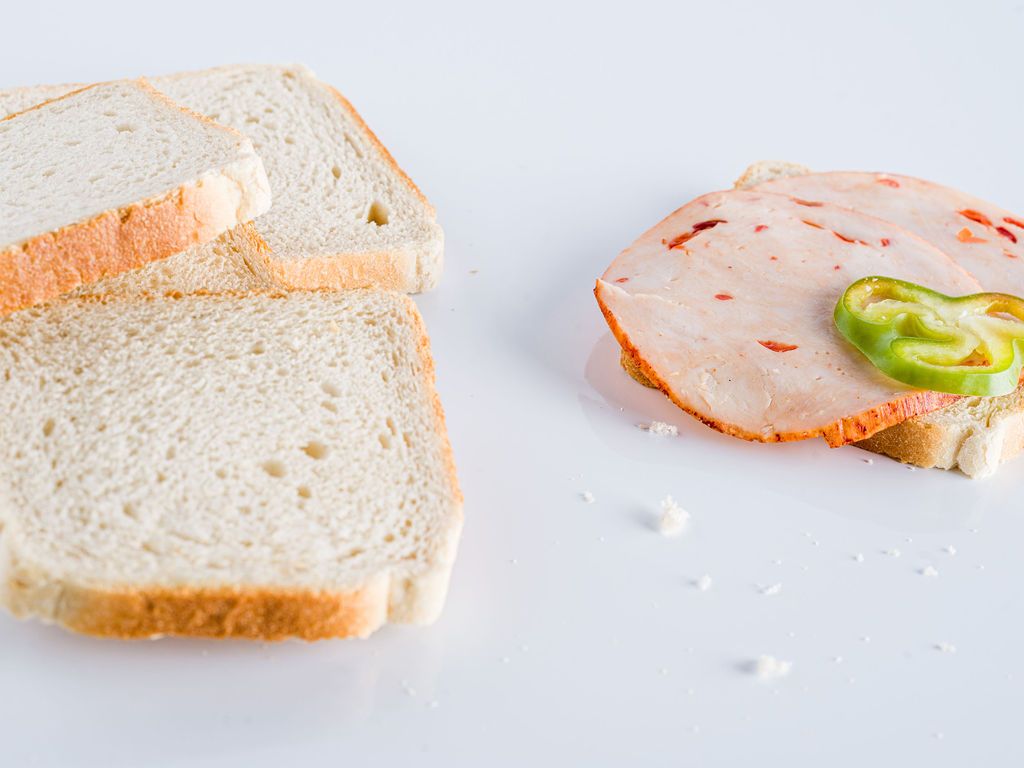

It is a must-have ingredient in all sandwiches and pariser salads, an attention-grabbing factor in cold dishes, the star of New Year’s Eve parties, and a permanent resident of lunch boxes. Thinly sliced or rustically chopped, or even as it is, bitten into. A variety of Parisians, hams, salamis and sausages have been with us for hundreds of years and seem to remain so for some time to come. In the October episode of the Büfé series, taste the feeling of retro!

Cold cuts are a meat product consisting of minced fillet and fat or bacon, seasoned with salt and various spices, stuffed into a kind of tube (e.g. a casing), often enriched with grain. It may be raw, boiled or smoked, and the preparation is intended to have a long shelf life. This was particularly useful in winter—if you ever went to a pig slaughter as a child, you will know that every part of the animal was used in this form, precisely to provide something to eat in the cold winter days. Of course, it wasn’t us who invented the genre of cold cuts—in fact, it is recorded that in 2000 BC the Sumerians were making such dishes, and later it was also popular among the Greeks as a theatre snack (for example, there is a reference to it in Ulysses.) The Roman emperor Constantine I tried to ban it in the 3rd century AD, because he associated its consumption with paganism, but he failed. The English equivalent, sausage, is derived from the Latin word salsus, meaning something preserved by salting (at that time, it was not possible to keep it fresh by refrigeration.)

In the 12th and 13th centuries, it was a popular dish among the European nobility (for example, the Italian mortadella was invented around this time), and by the 18th and 19th centuries it was also discovered by the middle classes, who loved its delicate flavor and exciting texture (the Polish kielbasa also became popular during this period.) Later, with the industrialized production, its reputation declined, partly because, due to the high volume, it was enriched with spoiled or inedible ingredients, which could lead to food poisoning. But the world wars of the 20th century gave a new impetus: food engineers from the Soviet Union, for example, traveled to the West to seek inspiration for nutritious, cheap and delicious food. After learning about the pariser (more specifically, the Italian bologna and German Jagdwurst products they discovered in America), Doktorskaya Kolbasa was born: a product with a high protein content, containing 70% pork, 25% beef, 3% eggs and 2% milk. Stalin saw it as the solution to hunger—and at first, as Stalin recalls, it was actually delicious when sliced on a thick slice of white bread. However, a similar product was already known earlier, as “parizer”, “parizerwurst”, “pariserwurst” or “párizsi kolbász” is mentioned in Hungarian sources from 1859. It was at this time that the first food factories were opened, followed by public slaughterhouses, which also led to the arrival of foreign butchers.

Traditionally, pariser was made mainly of beef and bacon, seasoned only with salt and pepper, stuffed into a beef casing and smoked. This high-quality ingredient then captured the imagination of cooks: it became a must-have ingredient in pasta and egg salads, in spreads and toasted sandwiches, but was also used as a meat substitute, grilled or fried, as a topping for stews or chopped into casseroles and pies. Over time, more and more types of cold cuts have appeared on the shelves, made with other, cheaper types of meat and additives (e.g. potato starch, protein.) Zala cold cuts, for example, are a traditional product with pork mosaics, while Italian cold cuts are made with nutmeg and pepper. Spring cold cuts are flavored with a variety of minced vegetables (e.g. carrots, peas), while the type called “Summer tourist” is also smoked, so that it has a longer shelf life. Smoked hams, sliced thinly, were less popular at the time—the public taste of the time was well reflected in the popularity of the aspen type, which was neither long-keeping nor of very high quality. However, it looked good on the plate, absorbing practically anything from horseradish ham rolls to pork tongues, evoking the flavor and texture of homemade jellies.

One of the first Hungarian producers was Sága, which started in 1917 when it was still an egg trading company. In the 1920s, they also bought and processed poultry and game meat, then became a distribution center during the wars, and finally continued to operate under the name Sárvár Poultry Processing Company from the 1940s, now as a state business. First only partially, then in 1996, it became completely Austrian property, at which time it also took the name Sága. Today, it is in Hungarian hands again with a British twist, after it was acquired by a family company, Master Good Kft., that has been engaged in poultry farming for four generations, and is present on the market as an innovative business that can reflect new nutritional needs thanks to a 2018 rebranding. Its products include hams as well as E-number-free sausages or frozen goods.

And now that we are talking about sausage… For me as a kid, Sága Füstli was always The Sausage (preferably the cheesy one) that we were looking forward to on New Year’s Eve. At the time, I didn’t even know that the history of sausage dates back hundreds of years: in Frankfurt am Main, it was known as early as the 1270s that pork thighs mashed with milk were seasoned, stuffed into sheep casings and smoked. It became a real hit in 1805, when the first Viennese sausage, also known as Frankfurter, was made by a Swiss butcher named Johann Georg Lahner. He lived and worked in Vienna, where the rules for butchers were more flexible than in Frankfurt, so he could be creative: he mixed beef and pork, added spices and water to the paste, then stuffed it into sheep casings and smoked it. The product was a huge success, even the Emperor of Austria became a regular customer. It was also known in Hungary, but over time the white meat version became more popular. Especially from the nineties, poultry meat became much cheaper, which also had an impact on the sausage market, although the quality of these products was far from the original recipe.

If we turn to dry goods, we have another traditional product that is known in many parts of the world, and many Hungarians abroad remember it with nostalgia—PICK salami. The country’s favorite salami is 152-year-old and was started by a crop merchant Márk Pick and was already featured in the Millennium Exhibition in 1896. Later, he also won an award at the Paris world’s fair, the company grew steadily, then World War I forced him to a halt, but only for a short time. Salami production was traditionally only possible in cold weather, but the heir, Jenő Pick, realized how he could cool the plant adequately. During World War II, they made liverwurst for the army and then, unfortunately, could not avoid nationalization. It did not stop during production, in the seventies, a huge factory was built with a sixty-meter maturing tower, and in ’99 the PICK Salami and Szeged Paprika Museum was opened in Szeged.

In 2014, the product became a typical Hungarian food, and the originality is indicated by the spiral national color ribbon, the white seal with the PICK logo, the red closing ribbon, the gold closing clip and the characteristic snow-white mold. The recipe is secret, but someone knows it by heart: the salami master, who has been István Függ for four decades. The pork is seasoned after slaughter, the paste is stuffed, then sent to be smoked for two weeks, and finally matured for three months. However, the name “winter” is not given because of its snowy appearance, but for the previously mentioned winter preparation, but nowadays it is made at any time, the quality is guaranteed. The company is committed to producing affordable, yet premium products, which may have led to the phenomenon that a bar of salami is almost a design product, when it is packaged, given and received as a gift to the hungry.

Although there are already domestic attempts to replace cold cuts with plants, nothing makes these products less popular. In short, if you choose cold cuts from store shelves, look for history and the flavors of childhood will come with it. In kaiser rolls, with sweet pepper, maybe a few dots of Piros Arany, the Hungarian paprika paster—because that’s the way it is.

Photos: László Sebestyén | Web | Facebook | Instagram

Source: Origo, Mindmegette, Vendéglátás Magazin, Index, Russia Beyond, Atlas Obscura, National Geographic

Designers and manufacturers—Part 4 | Balázs Botos and Gyula Mihály

Law firm in Poznań with a simple style