Sometimes we eat it on the go, during a trip or for a snack, sometimes we get it as a gift, and other times we throw it in the shopping basket without even looking. Melting in summer, stiffing in winter, yet we cannot resist—it’s the timeless world of the chocolate.

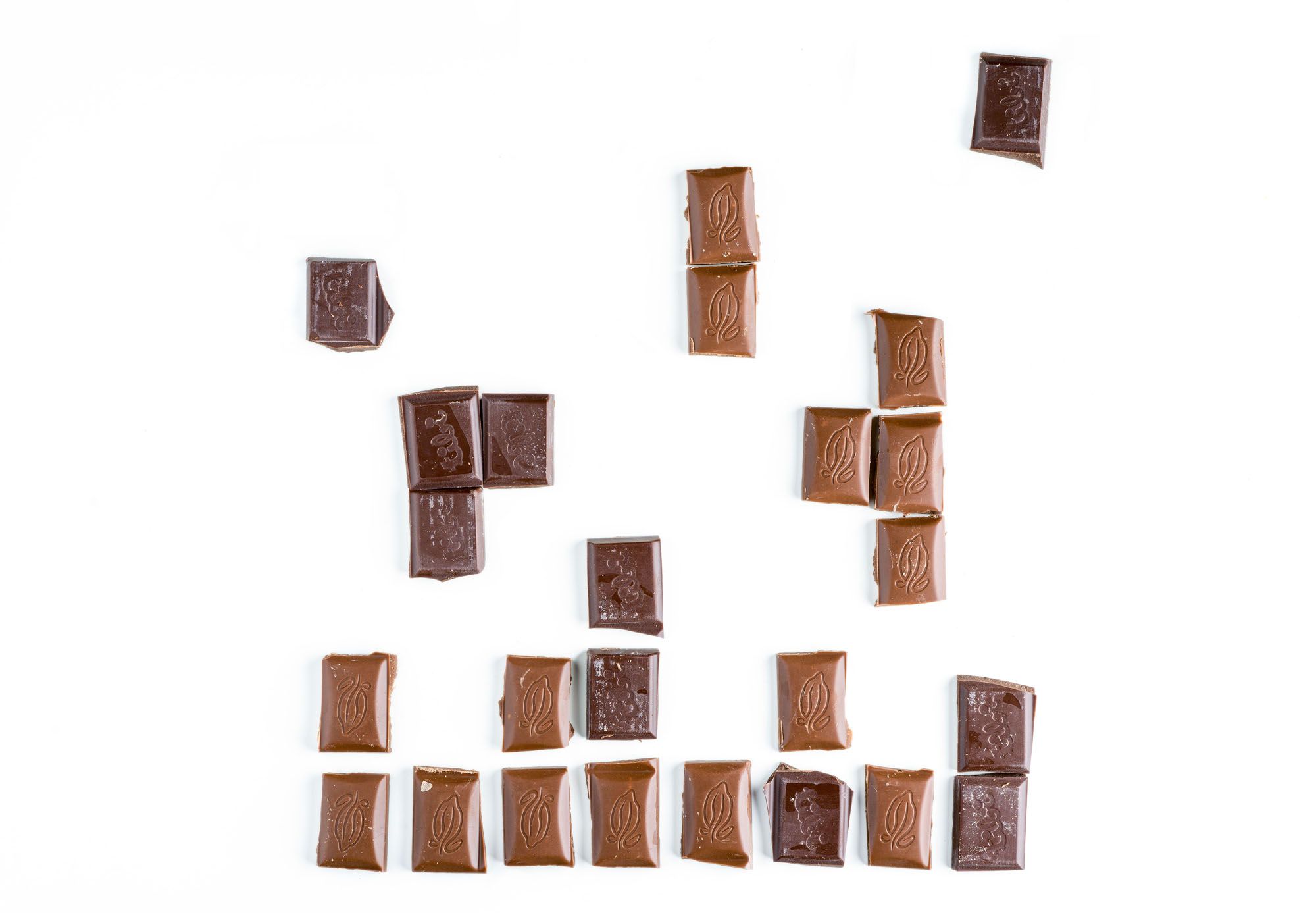

Chocolate. Everyone’s first memory of it is different. Everybody likes a different kind. We can argue into the night about whether dark or milk chocolate is better. What’s certain is that we always run out of it. Even if it’s a dubious quality chocolate Santa, and even if it’s a whole bar of hazelnuts (which, of course, we eat at one sitting, since it is actually healthy because of the hazelnuts…). Even the Katica food topping, which is still available today, occasionally loses a cube, even though its enjoyment value is quite far from outstanding. And although the palette has expanded a lot since socialism, some products have a rock-solid place on the list of customers’ favorites. Perhaps it’s the retro feel, the colorful, playful flavor of childhood that accompanies them. But how did the domestic chocolate bar industry get started?

We can fly quite long back in time to 1866 when a young, 23-year-old master confectioner arrived in Pest. His name was Frigyes Stühmer, born in Mecklenburg into a well-to-do Lutheran family, and belying his young age, he has previously worked for the German company Schulze, as well as in Hamburg and Prague. He came to Hungary because of his friend, Ferenc Nagy, a confectioner from Józsefváros, whose workshop he bought two years later and modernized it with steamer equipment brought from Dresden. This is how he founded the country’s first chocolate manufacturer, the Stühmer Chocolate Factory, with the unconcealed intention of “re-educating” the Hungarian public from unhealthy sugar candy consumption to quality chocolate. The business quickly became a success, and products (besides chocolates, cocoa powders, nougats, pralines, and bonbons) were available throughout Europe and were also rewarded with the Golden Cross of Merit with Crown by Franz Joseph himself. From the 1980s onwards, Stühmer sweet shops opened across the continent, but success and hard work came at a high price, and Frigyes died at the very young age of 46. He was replaced by his widow, Etelka Koob, and from 1910 by his son, dr. Géza Stühmer. Although development continued, the lack of raw materials caused by World War I, falling demand, and difficult political circumstances brought the company close to bankruptcy. However, a marketing move that still works today saved the company: famous artists were asked to design limited edition packaging.

In the 1930s, they came up with new products, such as Frutti caramel and Zizi, and in 1941 the tibi chocolate, still well known today, was launched. It was named after Frigyes’ great-grandson Tibor, and at that time, it was only available in dense milk- and dark chocolate varieties. The slogan (“not only Mum’s favorite!”) and the vibe of the product were aimed at a younger audience, with a noisy success. In the meantime, they also moved to a modern and state-of-the-art factory in Vágóhíd Street, but in 1948 they could not avoid nationalization. The family escaped, and the company continued to operate as the Budapest Chocolate Factory. Even after this, the story is messy because, in the 1980s, the name Stühmer was freely available, so it was bought by a company in Eger— and from them, the descendants repurchased it. However, they could not move back to the factory on Vágóhíd Street, because although there is chocolate production still today, it is owned by Bonbonetti Choco Ltd. and the tibi chocolate is not made according to the old recipe either. Stühmer, however, gained momentum in the 2000s, thanks for example to Péter Csóll, who was a fan of the brand. After he bought the Eger confectionery shop, he decided to give the brand a boost. He sought out old employees (for example, Béla Borbély, a confectionery specialist) who remembered the original recipes. In 2008, the new plant was built in the village of Novaj, and the production of the iconic sweets (for example, Korfu kocka, Ezüstdesszert) started, but Melódia, which used to belong to Szerencsi, was also produced here.

The Szerencs Chocolate Factory mentioned above is younger, but its history is just as tangled. The Magyar Kakaó és Csokoládégyár Rt. (Hungarian Cocoa and Chocolate Factory Ltd.—free translation) was founded in Szerencs in 1921, and it produced very high-quality products thanks to the fact that the milk necessary for chocolate came from its own cowshed, from controlled conditions. In the 1930s, depots were opened all over the country and also exported abroad, but in 1944 German soldiers arrived at the factory to seize the machines. The then leader, Frigyes Liechti, managed to prevent it, but not the nationalization: after 1948, the company continued to operate under the name of Szerencsi Édesipari Vállalat (Szerencs Confectionery Company—free translation). Although it was kept under control, it was given a prominent role in the 1960s; for example, one third of the chocolate products available in the country was made here, with 2,400 employees and 18,000 tons of goods a year. The company was privatized in 1991 when it was taken over by Nestlé of Switzerland. And why is this important? Because, for example, it is the birthplace of Boci chocolate, which has featured the iconic cow on its packaging since the 1950s. Today, although the factory remains, and Boci chocolate is still popular, all the bars are now made in the Czech Republic. Very similar processes took place here and in Poland, by the way. In Poland, Karol Wedel made caramel and chocolate from the mid-1800s, also for medicinal purposes. The products later became even more popular and reached Japan. In 1839, at our Czech friends, Jan František Černoch founded a factory called Luna, which by the end of the century had 8 factories across Prague. They were able to keep going during the war, as chocolate provided soldiers with a cheap energy source that could be used quickly, and after the war, they imported more cocoa beans than Switzerland. The Orion brand, for example, managed to survive with thousands of employees.

And speaking of big brands, there’s a chocolate bar that’s made its way into recipe collections. The no-bake, minced biscuit-crumb-chocolate chip cookie was one of many people’s first experiments in the kitchen and made its way into the notebooks as a homemade Sport bar. The original has also been with us for a long time: on 20 August 1953, the Népstadion opened, and to mark the occasion, the iconic Sport bar was unveiled, produced by the Csemege Édesipari Vállalat (Delicatessen Sweets Company—free translation). 25 grams of rum and chocolate bricks, made using a handicraft technique, in a two-layer wrapper, illustrated with József Szécsényi’s discus throwing gesture on the paper cover. Following the revolution, it was available under the name MHSZ Sport szelet, the background of which was the campaign of the Hungarian Workers’ Party, the “Ready to Work, Ready to Fight! ” was a competition to promote sports. The demand was so great that even the foremen joined the production, yet after the change of regime, it could not avoid privatization. Under the ownership of Mondelez Hungária Kft., the 31g and XXL bar appeared, the discus thrower figure disappeared, and caramel, white chocolate, and hazelnut versions were also born, as well as Neapolitan wafers and ice cream. Constant advertising campaigns were used to keep the brand fresh; for example, in the 2000s, an American character with dreadlocks tried to help others in a spirited, well-meaning, but rather clumsy way. (Fun fact: the ads were originally for the Norwegian Japp bar, only the last frames were replaced.)

Anyway, the Sport bar is indelible from the minds of Hungarian confectionery fans forever. They emerged as a sort of transcription in our childhood: the Ízvilág product line included Kapucíner, Lottó, Bohóc, Autós, Szamba, and Eperjó. They were all very sticky and sweet, with a slightly artificial flavor, like orange or coffee. (The vigilant may notice that Kapucíner is now also made with the Sport logo, although it is supposed to be the original recipe.) The price to date is under 100 HUF, which makes us wonder what the ingredients are, but it’s a similar story with, for example, chocolate bananas: they’re a bit like marshmallows, butterscotch, or even fruit caramel combined with chocolate. We don’t necessarily understand them, but we are not mad at them for existing either. Those who really want a premium treat can choose from the macskanyelv (cat’s tongue) or the konyakmeggy (cognac cherry bonbon) developed by Emil Gerbeaud—but that’s another story.

Photos: László Sebestyén | Web | Facebook | Instagram

Source: Origo, Origo, Santa Barbara Chocolate, Culture.pl

Jewelry collection of flower buds cast in porcelain

The iconic Jaguar E-type is reborn!