What do we think of cob? How true are the misconceptions surrounding folk architecture, and what potential does an architect see in the material? Ádám Bihari goes back to the solutions offered by nature, responding to the questions of the present. Interview!

Nowadays, there is a renaissance in environmentally conscious and eco-architecture and the use of natural materials. Where did your commitment to earthen architecture come from?

I think it originates in my childhood. Order and disorder go hand in hand in the world, but I’m definitely a tidy, order-building person—I used to organize everything when I was a little boy. Nature also has an order, which we sometimes understand but often only feel. Even when I was very young, I remember being very sensitive to the fact that I could not reconcile our human activities with the natural order: I am thinking here of the immense waste production. As an architecture student at the Budapest University of Technology and Economics, you can be exposed to a lot of brilliant new influences. Such influence was the passive houses that were spreading in this country at the time, which I liked very much at first. What a waste-free energy consciousness! Then I took Dr. Erzsébet Lányi’s course “Structures of environmentally friendly construction”, which was a milestone for me.

I realized that the issue of sustainability in our buildings is not just about saving energy during their use, but also equally important is the issue of built-in energy and materials, as well as recyclability after demolition. We call this a whole life cycle assessment.

With this knowledge, I was looking for my place in architecture in a way that my sustainability system would allow me to practice architecture without compromise. Then it came in handy that my father, as a company director with a law degree, regularly took me and my little sister to open-air museums and country houses—I had an insight into folk architecture. That’s when all came together: the most sustainable architecture is folk architecture, or in other words, the vernacular architecture, using local materials and traditions.

How do people feel about cob houses and what are their first thoughts or misconceptions about them?

It is perhaps the most important thing to stress that I am not at all trying to persuade people to give up their comfort level and move back to their traditional mud-brick rural houses.

I would like us to start looking more closely at the building culture of our vernacular architecture, and to give new answers to the questions of the present, based on old solutions. We must adapt the logic, the methodology, not the whole procedure: we must develop it on new grounds.

It is important to underline that the negative image of existing cob houses is often based on real experience, but almost without exception these are not due to defects in the adobe house itself, but are the result of improper restoration. Unfortunately, along with industrialization, a modernization process began in the building industry, which did not value the traditional building culture based on loam and refused to use its traditional methods for the necessary maintenance and renovation. That is why many mud-brick houses today still have vapor barrier cement render, plastic insulation, and on the inside, plasterboard or washable plastic paint. All of these are results of renovations made with good faith, but they practically ruin the house, and then the mold, moldiness or even loss of strength is blamed on the cob house. The truth is the opposite: a mud house would work perfectly well if it had been handled professionally. Recent data show that there are 502 095 inhabited adobe houses in Hungary today. This number, including empty houses, rises to 624 350, which is a figure that should not be ignored. But luckily, new cob houses are also being built: our architecture office deals almost exclusively with such commissions. A common misconception about new-build houses is that you can only build a folk-shaped house out of mud bricks—this is of course not the case, it’s just very much ingrained in the public consciousness. Cob is a contemporary building material that offers a wide range of architectural possibilities.

Today you can relate to cob houses in several ways, to make these ideas better known or more popular. Exactly what initiatives are you working on and what are your goals?

Even as architecture students, we felt that this was a niche market. Together with my friends Boldizsár Medvey and Gergő Radey, we have been chewing on the topic for years, and then I met Vera Holczer during my Erasmus scholarship in Grenoble, France. Vera happened to be in town for the research center on earthen architecture too. On our return home, we decided that we had to start the process that had been ongoing in France for thirty years. Thus, the four of us formed the Sárkollektíva (“Mud Collective”)—we organized art weeks for students and held building camps, five in one summer. Luckily, this movement is still alive today: Gergő is still at the forefront of the building camps as part of the Nagyapám Háza master craftsman program, which was established thanks to the support of András Krizsán, president of MÉSZ.

Then, in 2017, we launched the Regio Earth festival, also based on the French model. This is an international event on adobe, where you can get to know cob and its professionals in a festival atmosphere, not just at a conference. Speaking of professionals: this is the most sensitive part of the business, as very few people deal with adobe on a professional level. This is why we founded the Association of Environmentally Conscious Builders in 2018 with the best of the best in the Hungarian profession: with this association we can now represent the cause of adobe in a professional way as a civil society, and pass on the accumulated knowledge through educational programs to create a strong professional team.

Your ambitions also include the use of cob in other areas, such as the clothing collection for the Gombold újra! competition, which later became the MÉLAM brand. Tell us about this project!

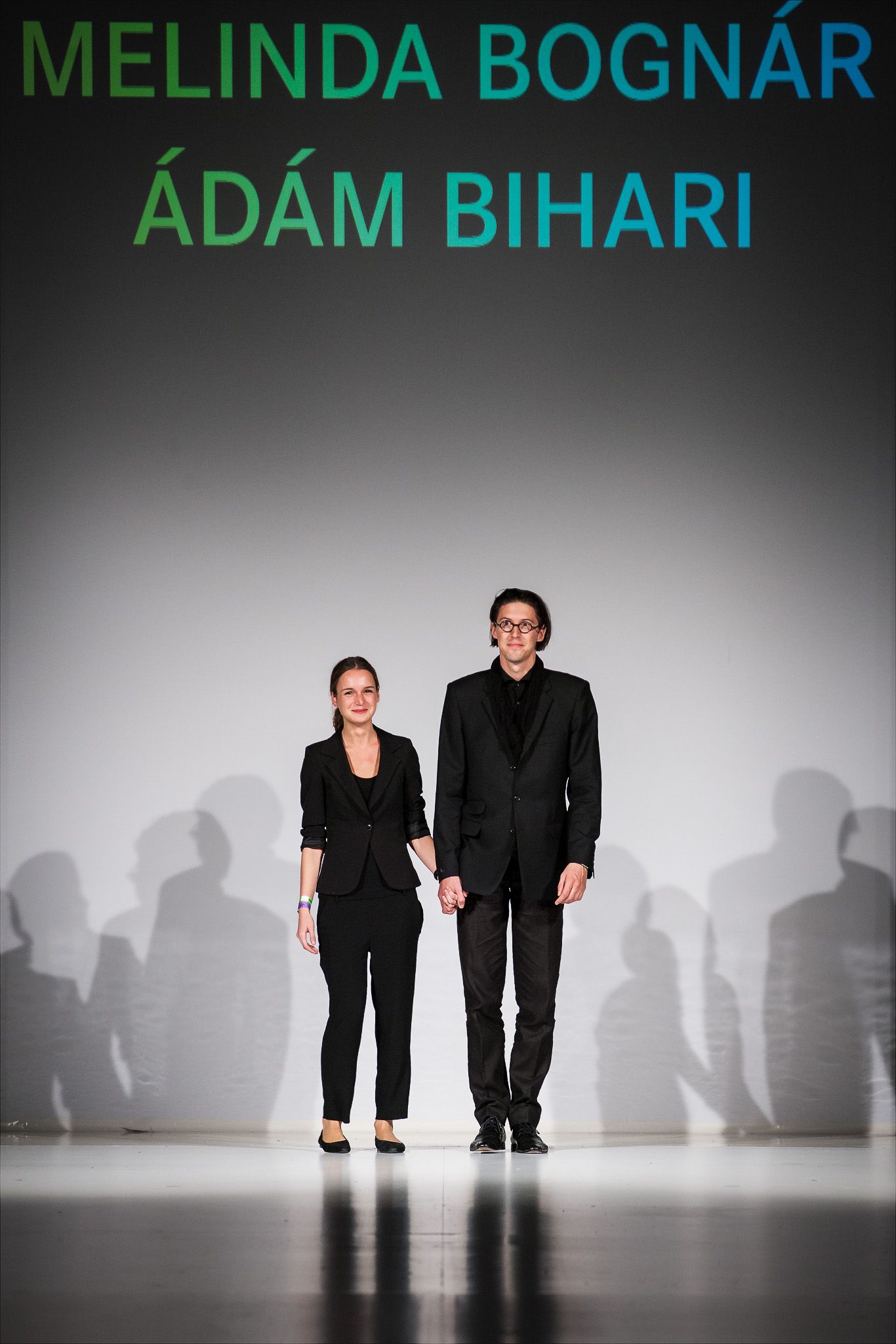

It is a very interesting project: I am convinced that cob is not just a material that is outdated, and not just a building material. Therefore, it has long been a dream of mine to do something with it in the design field. My architect friend Melinda Bognár had an affinity for fashion design, and it was her idea to enter the Gombold Újra! competition for young fashion designers with an adobe theme. From this we came up with our VÁLYOG collection, which made it to the finals. MÉLAM is currently at a bit of a standstill, but as soon as we become time millionaires, we’ll bring it back. We also have a lot of ideas for objects, for which we might ask Anna Lébényi, founder of VUUV Works, for help.

What architectural project are you currently working on? How do you see the interest of clients in cob has grown over time?

Currently I run a construction company based on the use of natural building materials called Naturarch. This now has several branches: the architecture office I mentioned before, but we also manufacture and build. In terms of construction, we have a growing number of very interesting projects: we are currently working on the interior design stucco of a super-luxury residential building on Rózsadomb. This was designed by interior designers in Paris and my former French employer was originally asked to do the work, but they were not able to do it because of the scale and the distance. Now I get to work with them again for a bit, which I used to love a lot.

We’re also working on the renovation of the Kinizsi Castle in Nagyvázsony, where the architects have designed an interior stucco made of adobe—another very exciting project. Here we have also built Hungary’s first visible tilting cob wall, which will also serve as a decorative element in the fence of the reception building next to the castle.

These two large-scale projects prove that cob is not just a building material for poor people, and fortunately more and more people are coming to see it that way.

On which areas would you like to focus in the near future? What are your plans?

I have many plans, of which I would like to highlight two, which have been in preparation for a long time. Next year, I would like to start a doctoral school at the BME, where Dr. Péter Medgyasszay, one of the most respected researchers in the field, would be my supervisor. Our research will focus on exploring trends in the use of natural materials and developing a contemporary building system. Our other big hit is Naturarch’s new business line, the building materials trade. Later this year, we will launch our “eco-building” service, which will exclusively sell natural building materials. This will also make life easier for builders and contractors, who will be able to buy all the natural products that are currently still considered specialties in the conventional building industry from a single source, and from specialists.

Sárkollektíva | Facebook

Naturarch | Web | Facebook

Regio Earth | Facebook

Interior design plans of the Porsche minibus

Earphones showing all parts