Each year sees more and more projects offering alternatives to urban co-living and community housing. Co-living and cohousing are fundamentally about tackling loneliness and the housing crisis, while sustainability and environmental considerations are becoming increasingly crucial factors. But what makes such an initiative work in practice and how can it respond to current challenges? Here comes the latest HypeLab episode!

Community housing covers a fairly broad spectrum: from building apartment complexes of several hundred people specifically for this purpose, through a community of friends building together, as far as the Swiss girl, who recently advertised her balcony as a camping site. The underlying principle in each case is that the individual, or nuclear family unit, doesn’t live alone in homes but shares their living space to some extent with others. This article will now focus on examples where the housing itself is specifically designed for this purpose. Two opposing schools of thought exist on this topic, one of grassroots initiatives and one of the top-down property investments.

Although communities have been living together essentially since the beginning of mankind, the first modern cohousing building was built in Denmark in 1966. The reason why this was so different from previous 20th-century attempts to implement community functions in apartment buildings (which failed in most cases) was that it was an absolutely grassroots initiative. Six young people have bought a building plot on the outskirts of Copenhagen to build a community home complex. This ultimately failed due to opposition from neighbors, but they attracted massive press coverage: more than 200 people wrote letters expressing their interest in shared housing. The first cohousing building was completed at the second attempt, where the 27 families moving in also had a say in the design process. The social aspects of cohousing, especially the benefits for children, have been the most appealing features for young families, but the new lifestyle has also become attractive to single people and the elderly. By 1982, all of Denmark was in cohousing fever: they had built 22 community homes by then.

The first and last initiative of this type in Hungary was the Miskolc Collective House, built in 1979, designed by architecture students to live and work together. The building consisted of a large common area and living cells, with no transient spaces to allow for a retreat or to leave the house without the knowledge of others. The collective house operated only for ten years and failed during the period of regime change. It is now a simple condominium, and no similar construction has been started in Hungary since.

Large-scale cohousing industry

The Scandinavian experiments of the 1970s attracted the attention of real estate investors worldwide, and one by one, they started to build huge cohousing complexes resembling adult dormitories. The world’s largest 550-bedroom cohousing building, the Collective Old Oak, was opened in London in 2016. Many positive, but also a lot of negative reviews are circulating about the building on the internet. They say that you get a hole overlooking a freight station in exchange for a peppery rent and that the community doesn’t necessarily work cohesively and harmoniously because of the large number of residents. Despite this, Collective is expanding, with three New York buildings scheduled to open this year, one of which was designed by Sou Fujimoto. These complexes function as a kind of mini-city, with exhibition spaces, theatre, lecture and coworking spaces, as well as a restaurant, rooftop bar and gym. The question is, can so many people really live as a community? Is it enough to have a small bedroom, without having transitional spaces where residents can spend time alone or in small groups?

The issue of catalog homes also arises: in these cases, the apartments are usually fully furnished and equipped, leaving little room for personalizing the living space. This gives a kind of impersonal and temporary feeling to the concept of home. It is no coincidence that residents of Noiascape, also in London, typically move in for a fixed period of three to twelve months, usually for work or study. Thus, while these buildings can provide a brilliant alternative for specific living situations, they are unlikely to be able to adapt to the changing needs of their occupants over the long term. They work best when they are occupied by tenants in similar shoes at the same time.

The big public opinion poll

In 2018, IKEA’s innovation lab, SPACE10, launched a large-scale public opinion survey to better understand potential cohousing residents. This method aims to implement a bottom-up design methodology while not proceeding from a specific community. The survey, called One shared house-2030, was eventually answered by 14,000 people from 147 different countries. The results showed that the majority would prefer to live in small communities of four to ten people rather than in complexes of several hundred. Respondents would prefer to live with childless couples, single women and even pets, rather than with small children or teenagers. There would also be strong democratic principles against large-scale cohousing arrangements: new members would be voted on and equal ownership would be required. The main concern would be the lack of privacy, and although shared spaces would be furnished by designers, people would prefer to furnish their own living quarters. It is clear from these figures that actual needs and the several hundred-person real estate investments are generally very far removed from each other.

The only question is whether a study carried out in 2018 can really be relevant for a cohousing project for 2030? Just think of the pandemic that erupted in early 2020, which rewrote our routines and our relationship with our homes in a matter of seconds.

In search of the ideal cohousing

So then, what does an ideal cohousing building look like in practice? As we can see, it is not necessarily working if they are set up to meet the needs of a specific community, because communities can break up easily. Predetermined fixed functions and spaces are also unsatisfactory, because they can’t be flexibly adapted to changes that arise, such as increased working from home and the need to contain the spread of an epidemic.

This issue was addressed by Norwegian architecture studio Helen & Hard in the Scandinavian pavilion at the 2021 Venice Architecture Biennale. Commissioned by the National Museum of Norway, the exhibition was entitled What We Share, and demonstrated how architects can design communities based on sharing. They exhibited a cross-section of a flexible spruce-framed community house, developed together with residents of a Norwegian cohousing project. They wanted to find out which functions people would be willing to move from their private homes into the shared spaces. The pine structure would also allow for flexible community space design: residents could design DIY furniture and partitions, constantly transforming their living space.

The Vivahouse project, although it is not an answer to the problem of catalog housing, could serve as an important example by combining social care and the recycling of unoccupied buildings. Demonstrated in a disused shopping center in London, the prefabricated modular housing system aims to convert vacant commercial properties into cohousing spaces in no time: the entire system can be constructed in 24 hours in existing buildings, requiring significantly less time and money than a conventional construction project. The idea is closely linked to sustainability efforts and the need to prevent building demolition, which is a major carbon emitter. This method could also work effectively in situations such as the current Ukrainian-Russian war, which has forced millions of people to flee their homes. Such a construction could provide a quick and inexpensive solution, where people could get through this difficult period in a civilized and communal environment while regaining a slice of their privacy.

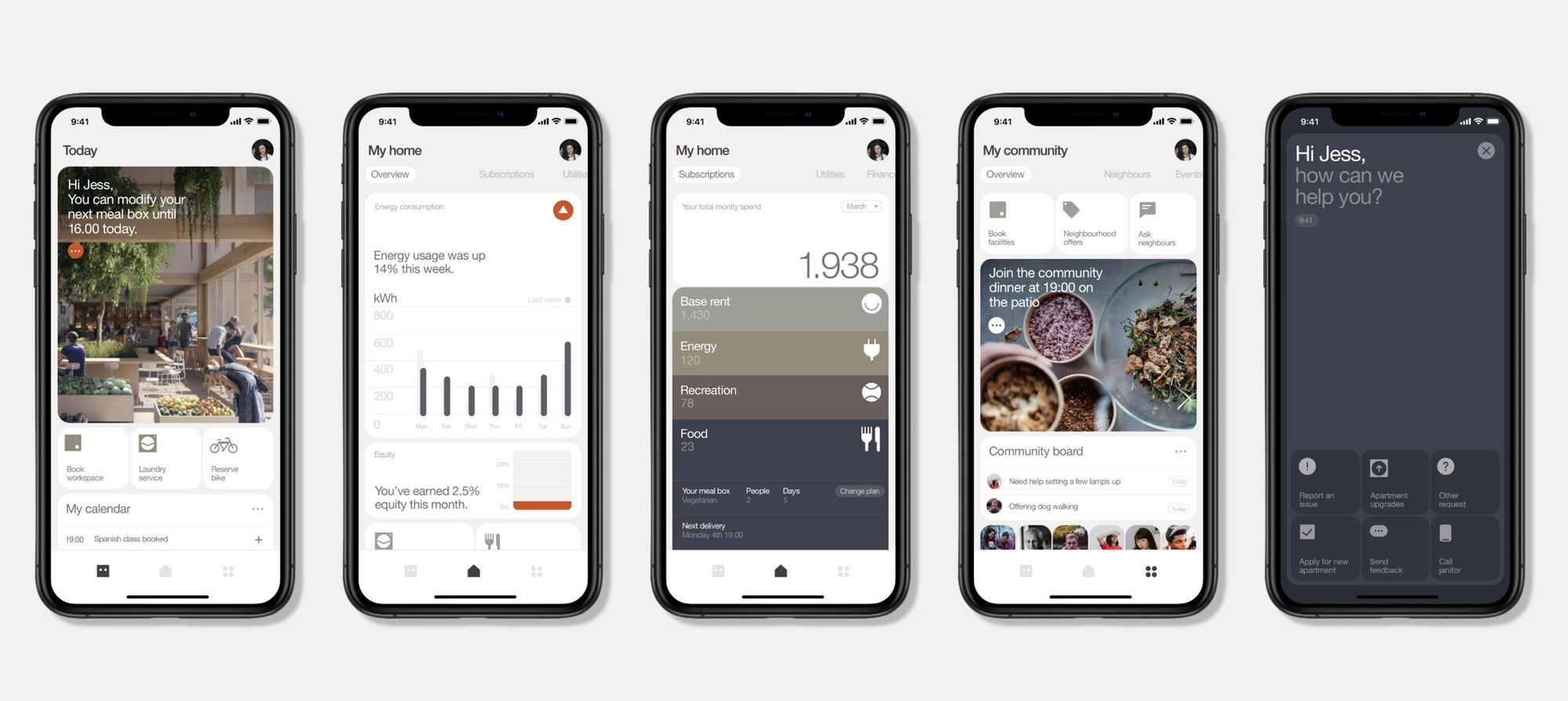

Another alternative is The Urban Village Project by IKEA SPACE10 and architectural studio EFFEKT: a subscription-based community housing idea with sustainability and circular construction at its core. Here again, the concept is based on a modular wooden construction system, which allows a wide range of apartment types to be configured, disassembled and reassembled, or swapped between families as required. In addition to basic rentals, residents could also choose additional services such as dining, media, insurance, transport and other leisure activities through flexible subscription services. Environmentally-friendly services such as composting, renewable energy and local food production, as well as tool sharing, could also be used to access better deals. Residents would also be able to buy shares on a monthly basis, gradually increasing their ownership. The construction would be financed through long-term investments, pension funds, future-oriented companies and municipality partnerships.

While many cohousing projects designed for specific living situations can be successful, we conclude that flexibility and customizable spaces are essential for a building to remain capable of long-term renewal. And it is important to remember that cohabitation can only be truly successful if there is always room to be alone.

“A minimalist oasis with plenty of possibilities” | A design concept store opened in Cluj Napoca

Ukrainian women share their story at MOME