We can discover how a keyboard instrument works, use a ball track to lay out the famous theme song from Harry Potter, paint sounds with a holoventilator, or even hear how our own name would sound if it were a tune or even get into the shoes of a conductor. We visited Creative Sound Space, the new interactive exhibition of the House of Music, Hungary. We talked to Dániel Váczi, instrument maker and musician, the creator of the conceptual design, and András Gross and Tóbiás Terebessy, the members of the Medence Group, about the uniquely designed installations.

As a matter of fact, Dániel Váczi is interested in everything that relates to sound. He is, for example, behind the development of the glissotar wind instrument, which he created with Tóbiás Terebessy, one of the founders of Medence Group. Besides the Guthman Prize-winning instrument, the workshop is also linked to several other projects where they experimented with sound objects, such as the sound-producing instruments of the Bélam Workshop, the Melody Wheel designed for Müpa Budapest, or the sounding city fountain in Kőszeg, created in collaboration with Daniel. Yet, they admit that Creative Sound Space is their most complex and most extensive project to date, in which Dániel led the activities—in their words—as a conductor.

Márton Horn, the director of the House of Music, approached Dániel more than two years ago to create an “instrument petting zoo” as a complementary exhibition to the permanent display Dimensions of Sound—Musical Journey Through Space and Time. During the brainstorming process, it soon became clear that by putting out an instrument, visitors wouldn’t be able to play it. Plus, the device would break down quickly, so it would fail to offer an experience. “We based the design on how to create installations that would allow visitors to experience music in a way that would make them feel not only passive recipients but also active participants,” said Dániel.

“We not only wanted to create instruments in the traditional sense, but everything related to sound,” he added.

After considering several other factors, Dániel’s ideas were finally put together into a coherent and functional design with the members of the Medence Group, a team of more than thirty people. “Several aspects had to be brought together in a cohesive way to make the exhibition work both conceptually and operationally: the sound installations in the Creative Sound Space engage both young and old, are simple in appearance yet playful and of high quality—they fit perfectly with the other quality elements of the House of Music,” András noted.

As they pointed out, the space aims to serve as a kind of palace of musical wonders, offering visitors an experience that will make them braver and more open to music and sound. Furthermore, the elements of the space encourage experimentation and interaction while providing a sense of joy and achievement. “It’s quite a challenge to create an installation that works for children and adults alike,” András reminded me. “It should be engaging for a while but not too long, it should be easy to use, but the process of reception should still be deep enough for a more intuitive, introverted person: the task was to create a set of experiences that is placed on a very broad horizon,” he explained.

A key aspect in creating the eight installations in the space was making real acoustic sounds without electronic control. Furthermore, as Dániel pointed out, “it was also important to appeal not only to the lay public but also to the musically trained visitors.” One way of doing this is to engage the user with visual stimuli in addition to the sound experience. One such installation is the Tonepainter. As its name suggests, it allows you to explore the relationship between sound and the visual images it displays. The experience is further enhanced by the visualization being created using a holoventilator, so that the emerging graphic patterns create the effect of floating. A different kind of relationship between sound and visuality is represented by the so-called Chladni-Theremin, where fine grains scattered on a steel plate are transformed into various geometric shapes by the vibration of the sound.

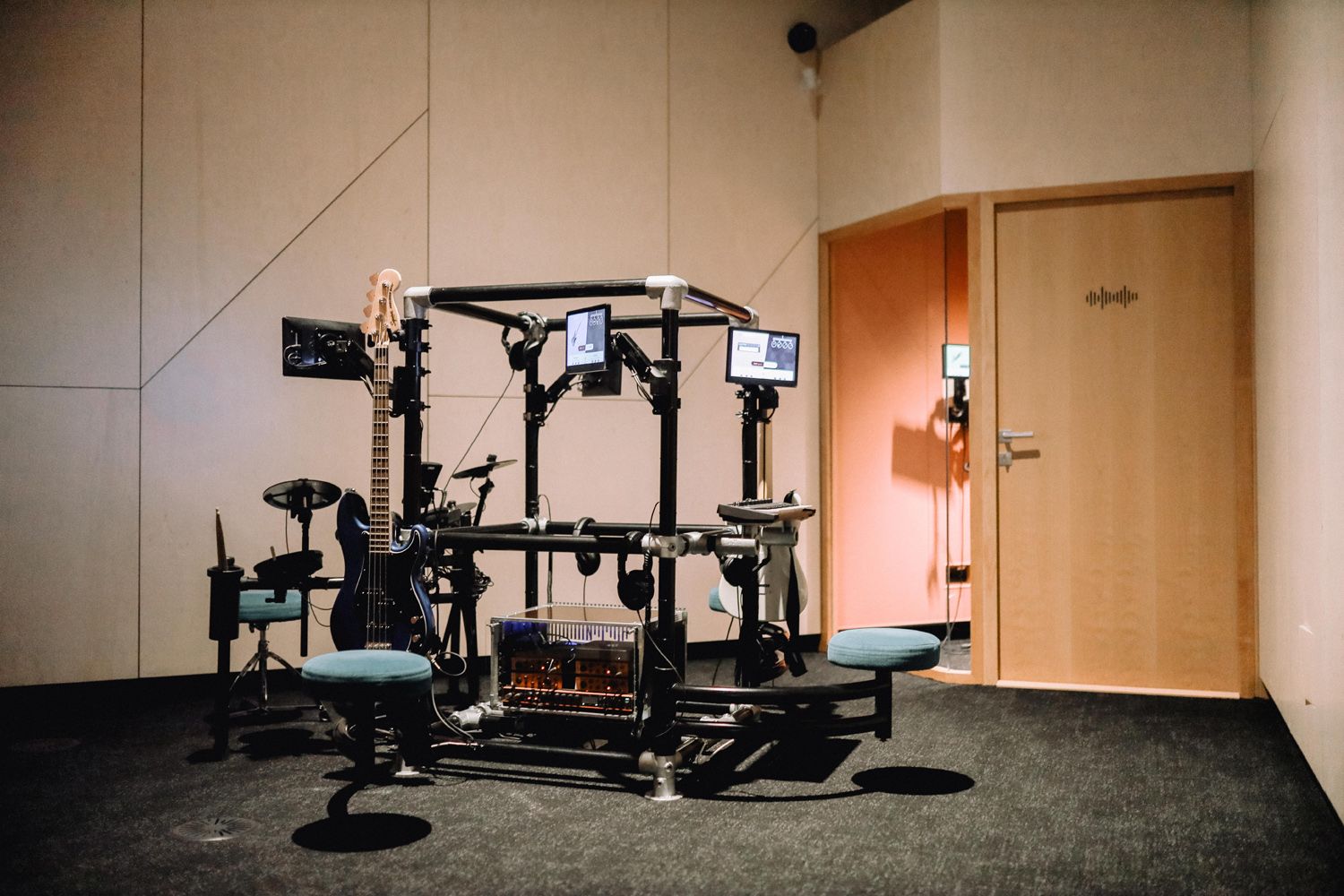

The spacecraft-like Rythm Mobile at the entrance also condenses a complex form of sound and visual experience. “What’s exciting about this device is that you get a very complex experience through a very simple and mentally effortless movement, a manual drive. At the same time, the user is present in the whole process, providing the speed of the story. Just as a musician can experience this while playing an instrument, a layperson can experience through such an installation what a musician feels when playing a professional piece of music,” Tóbiás highlighted.

“Basically, we are surrounded by many sounds all the time, so for me, it wasn’t necessarily the musical sounds that were interesting. For example, if you take a familiar sound out of its original context, it has a completely different meaning. I think the same thing happens in the Creative Sound Space. In the case of the Musicalmarble, for instance, there is a ball rolling in a trough, which has a temporality, and at the end of the trough, the ball comes to an impact point: it’s a kind of visualization of a melody, so it gives a visual sense of how a temporal event is created, which I think is very exciting,” he added. Dániel also revealed that the first version of the Musicalmarble track, which illustrates musical pathways, was actually developed with his wife for their children.

Still, the dearest thing to the instrument maker is one of the most impressive elements of the space, a digitally controlled, acoustic-sounding ensemble of musical automatons called Orchestrion. When creating it, Dániel drew a lot from György Ligeti’s ideas on modern organ building, much of which has not been put into practice to date. As Dániel pointed out, the apparatus has much more potential than it shows. He hopes that the Orchestrion will start to have a life of its own outside the museum walls: even contemporary classical and pop music composers can write music for it, electronic musicians will be able to improvise on it, or it can also be used in museum pedagogy.

“The installations can actually be seen as prototypes: an idea has given birth to a working object or a work of art that could even be developed further. As a creator, it’s very important to experience how an idea takes shape and becomes a working reality—that’s what gives it the most power. In the case of the Creative Sound Space installations on display, it also occurred to me that some of them could be further conceived as take-home products or toys that could reach a wider audience beyond the walls of the House of Music,” András concluded.

The Creative Sound Space will be open to the public from 18.05.2022, during the opening hours indicated on the House of Music, Hungary website.

Curators: Márton Horn, Endre Vazul Mandli (House of Music, Hungary)

Concept: Dániel Váczi

Installation design and implementation: András Gross, Tóbiás Terebessy (Medence Group Ltd.)

Interior design: András Báger, Áron Szabó (Bahcs Művek Ltd.)

Photos: Dániel Gaál

Dániel Váczi | Web

Medence Group | Web | Facebook | Instagram

House of Music, Hungary | Web | Facebook | Instagram

Magazine

Are the eastern EU Member States catching up or lagging behind?