In the history of 20th-century design, along with Marcell Breuer, László Moholy-Nagy and Ernő Rubik, Eva Zeisel, or Zeisel Éva is known worldwide. But do we know at home, who she was at all? Born as Amália Éva Stricker in Budapest in 1906, the designer’s long career culminating in the United States of America is described by most monographers through an adventurous biography, full of so many astonishing twists and turns that it almost begs to be made into a film. In the ninth part of our series, we would like to present the Hungarian-related events of Eva Zeisel’s career, as well as her defining and epoch-making works, which can be found in the collection of the Museum of Applied Arts.

Written by Piroska Novák

Eva Zeisel’s diverse, playful character as a designer stems from her family roots: she is a descendant of the Stricker-Polányi family, a distinguished family of intellectuals, free thinkers, scientists and open-minded cosmopolitans.[1] With such ancestry, it is not surprising that Éva Stricker initially intended to become a painter; from the autumn of 1923 she studied at the Magyar Királyi Képzőművészeti Főiskola (Royal Hungarian Academy of Fine Arts—free translation) as a pupil of János Vaszary. Partly driven by her own motivation and partly at the suggestion of her parents, she changed after three semesters and turned her attention to pottery, based on authentic craft and craftsmanship. Jakab Karapancsik, a master stove and pottery maker, taught her the process of pottery making, from clay mining to discing, glazing and firing. It should be noted that Karapancsik’s name was brought to the world’s attention by Eva Zeisel’s later successes, and his work is otherwise not recorded in Hungarian ceramic history. This is exactly why the choice of young Éva Stricker is strange, since she could have enrolled in the ceramics training course at the National Royal Hungarian School of Applied Arts, which had operated since 1911 and had been teaching women since that academic year, but she chose an anonymous craftsman. After obtaining her qualification from the Hungarian Guild of Roof Tilers, Stove Makers and Well Diggers, she started working independently in the workshop she set up in the greenhouse of the family garden.

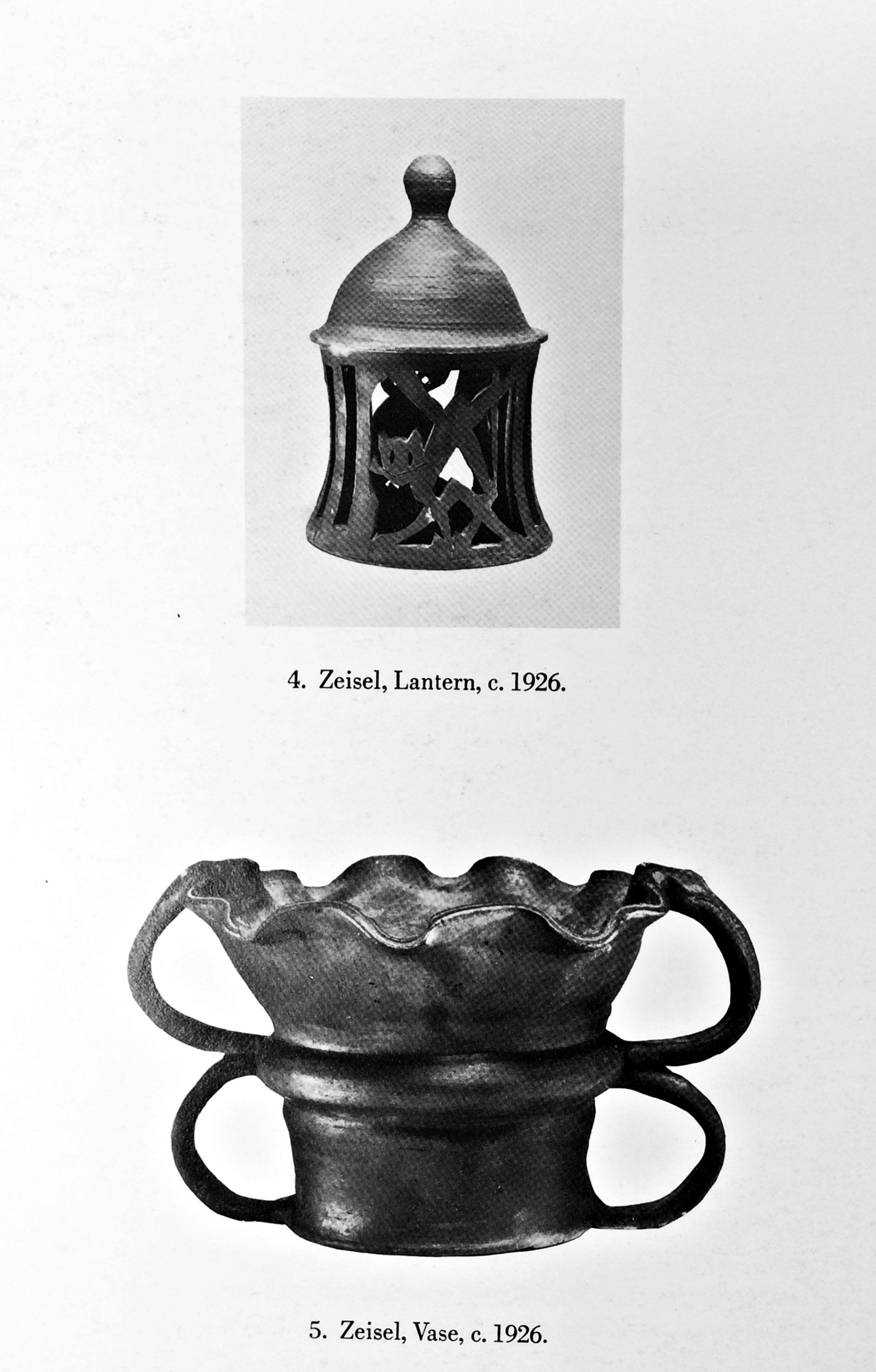

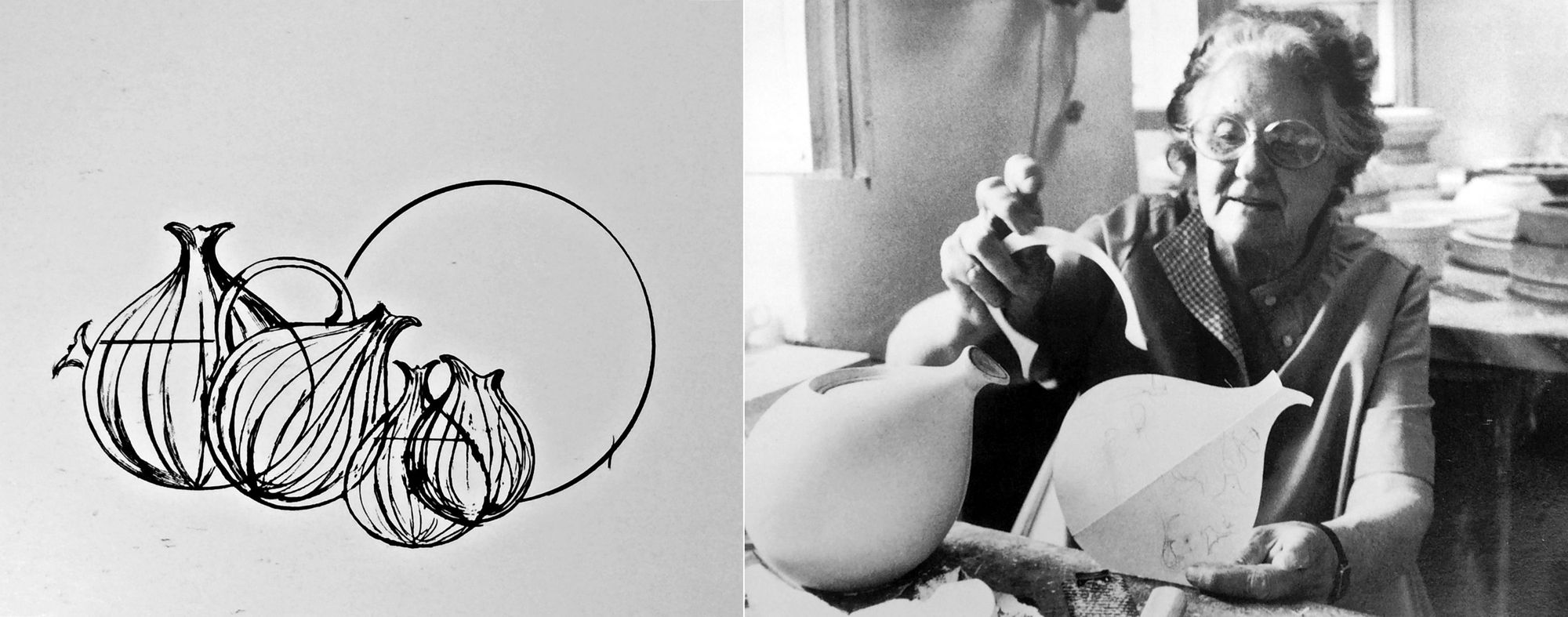

In the beginning, Éva Stricker made decorative and utilitarian ceramics in low-fired clay, fired in an open flame kiln, influenced by Hungarian folk pottery and the Wiener Werkstätte in Vienna. According to most sources, she achieved her first success in 1926 at the Philadelphia Exhibition of the 150th anniversary of the independence of the United States of America, where she was awarded a certificate of recognition.[2] As a fresh, previously unpublished research data, we can report that prior to this, the ceramist participated in the Budapest International Fair (BNV) held between April 17-26, 1926. Her objects were praised in the columns of the Esti Kurir journal.[3] It is thanks to this that Éva Stricker can be seen at work next to the disc, in a picture that has been published many times—this photo was first published in the Képes Műmelléklet (Picture Art Supplement) of Pesti Napló, immediately after the BNV, on May 1, 1926.

It is well-known that thanks to her success in Philadelphia, she was hired as a designer at the Porcelain, Stoneware, and Stove Oven Factory, founded in 1922 in Kispest, where she designed animal ornaments and small sets in the spirit of Art Deco Decadence. From here her journey took her to Germany, Hamburg, Schramberg, and then Berlin, where she created objects in the spirit of modernism, Bauhaus and Neue Sachlichkeit, using geometric forms and bright, colorful patterns to break up the austere silhouette.[4] In 1932, Éva Stricker traveled to the Soviet Union, partly because she was curious about the utopia that was being built in the name of the communist and revolutionary ideals. She worked here in such famous factories as Lomonosov in Leningrad, heir to the Tsarist porcelain manufactory, and the huge Dulevo Porcelain Factory near Moscow. Besides the principles of Suprematism, she was also introduced to the traditional porcelain patterned glassware of the Classicism period that served the Tsarist court. Éva Stricker, a professional potter, gained practical experience as a factory designer in the Soviet Union and Germany, which she successfully put to use in her later work.

In May 1936, Éva Stricker was arrested on charges of plotting to assassinate Stalin and detained for sixteen months; she was released from the Soviet Union in September 1937. Returning to Vienna, and seeing the continent’s boiling atmosphere, she and her fiancé Hans Zeisel traveled to London in 1938, where they married and emigrated to New York in October.

From this short, but eventful and culturally rich period, two Hungarian momentums are worth highlighting. In 1928 Éva Stricker returned home for a few months and worked as a set designer in Budapest. Her stage design for Nikolai Jevreinov’s monodrama A lélek kulisszái (Behind the scenes of the soul—free translation), depicting human lungs and a beating heart, performed on the Rendkívüli Színpad (Extraordinary Stage—free translation) of Ödön Palasovszky, was praised in the newspaper Ujság,[5] and later analyzed by architect and writer András Körner in an article written in a personal tone, in which he also wrote in detail about their friendship in New York.[6]

The other momentum is that shortly after her release from Soviet captivity, between 1937 and 1938, she was again contracted to the Kispest factory (by then Granite Porcelain and Stoneware Factory Ltd.), but unfortunately, we do not know of any surviving objects from this period.

In the United States, now as Eva Zeisel, she began her design career with incredible speed and energy. Initially, she designed a series of ornaments and souvenirs for small factories, then from September 1939, she began teaching ceramic design at the Pratt Institute with a highly practical and innovative approach based on the direct design of objects, manual modeling, and factory execution. The works of Zeisel’s students attracted a great deal of attention because modern European trends arrived in the US with a reception surrounded by some backwardness and reservations. Architect, industrial designer, and theorist Eliot Noyes, who at the time ran the design collection of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), also noticed the works of Zeisel and her students, so he recommended her to the Castleton China Company, who were looking for a suitable designer for a dinnerware set with a modern design that serves the etiquette of formal dining. Thus the design of the Museum dinnerware was born around 1942-1943, which is an extremely elegant, ethereal, and extremely sophisticated service. The object silhouettes are refined, their lines are delicately curved, and their design is both modern and classic. Some of the pieces are tall and stretched: according to the designer’s intention, they almost “grow out” of the plane of the table. The objects made of snow-white porcelain did not receive any decor, as the ceremonialness of the classic forms and the formal meal preferred the undecorated objects. The set was put into production and marketed at very high prices after the war. The Museum set debuted at the MoMA exhibition in 1946, where Eva Zeisel was the first female designer to have a solo exhibition opportunity; the showing Modern China was a huge success.

Zeisel then undertook a commission at the request of Red Wing Pottery, in stark contrast to her previous work, to create a casual, multi-purpose table set for informal meals in a loose “Greenwich Villagey” style. Her service called Town and Country is most often described by organic and even biomorphic attributives. These objects really attract attention with their extremely soft curved shapes, characteristic details, and colorful glazes. In Zeisel’s career, a break with the modern and geometric direction of Europe became clear here, which the designer called “pre-war” and “the compass and ruler era”. In the “post-war” period of World War II, her creative years of “lyrical” and then “poetry of communicative line” followed, perhaps most closely related to the aspects of Scandinavian design.

The salt and pepper shakers are usually singled out from the Town and Country set as fluid forms evoking animal shapes that later inspired Al Capp’s popular Shmoo comic and cartoon character. Zeisel, however, never forgot to mention in connection with these objects that they depict a mother and her child, as she intended to illustrate the personality of the forms conveyed between the designer and the client by the soft curves and expressive lines. The collection of the Museum of Applied Arts also includes a copy of the salt and pepper shakers, covered with a slightly metallic graphite glaze. These objects, along with several other outstanding pieces, were generously donated to the institution by Eva Zeisel’s daughter, Jean Richards, and the aforementioned András Körner assisted in the mediation and delivery of the works.

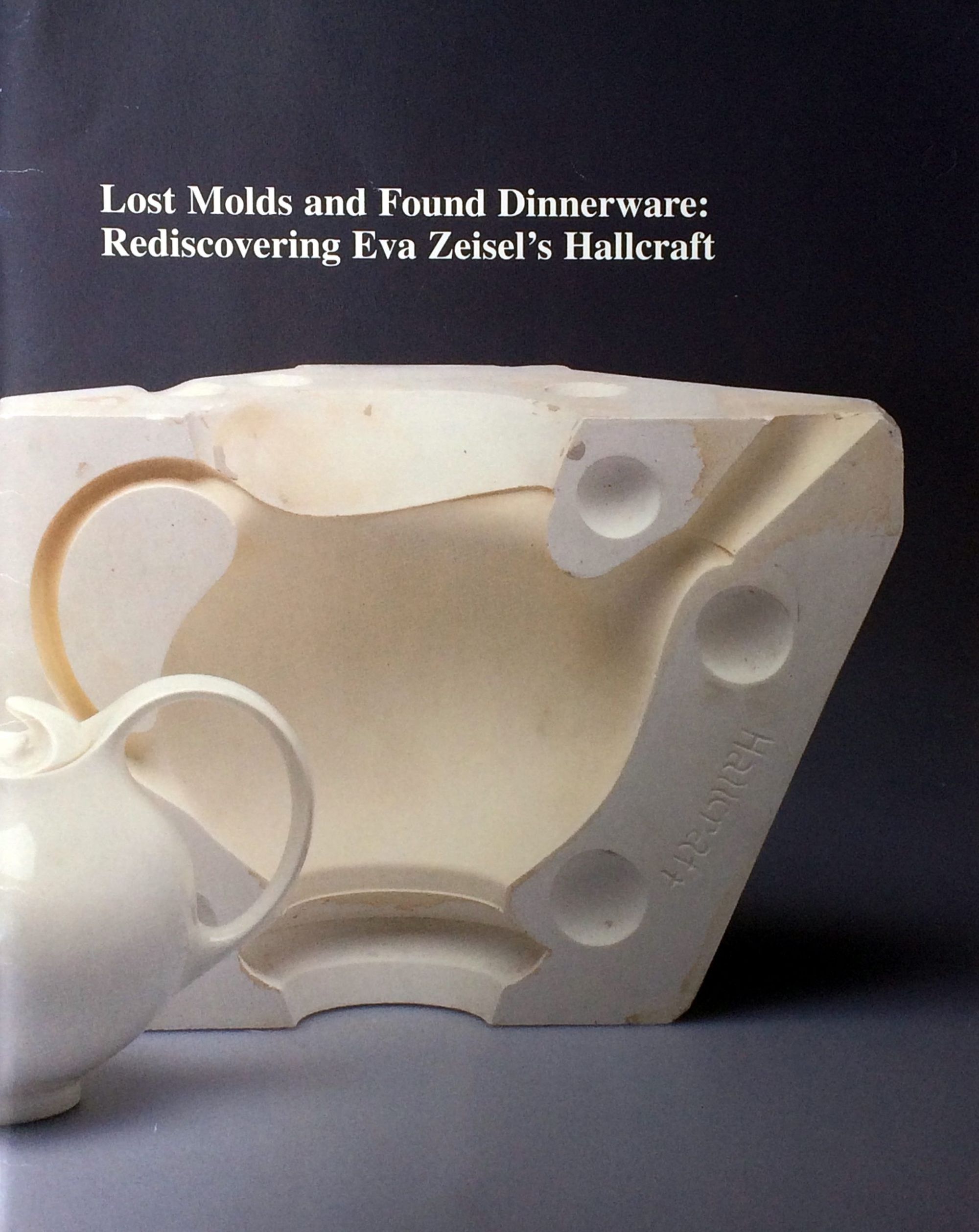

The Hall China Company commissioned Eva Zeisel to design a dinnerware service for a wide range of customers, suitable for both everyday and festive use. The pieces of the service called Tomorrow’s Classic were not accepted at first, and the factory leaders were later convinced by the president of the Commercial Decal Company to put it into production: the large and smooth surfaces of the object shapes are suitable for decoration with decalcomania. Zeisel had to create nine new decor designs in the year of production, and later three a year—for this, she involved her students. When designing the patterns, they had to make sure that each of them gave different character traits to the identical forms with sculptural beauty. As the name of the set shows, Zeisel once again blended classic and modern designs, and the end result was timeless beauty. She worked with tight-lined, wavy silhouettes, with handles almost “bursting out” of the shapes, inviting the user’s hand to touch. When designing the plates and bowls, she broke with the traditional circular shape and stretched the pots in a shape reminiscent of leaves, which also received an ergonomic handle. When designing the sets, it was an important principle for Zeisel that she did not create beautiful pieces in themselves, but families of forms that interact with each other, giving a unified, harmonious overall picture.

The use of decals generated great debates among professionals. Conservative designers and theorists despised this form of decoration, but the more practical side saw the marketing opportunity in it.

The Tomorrow’s Classic set has been an even bigger success for Zeisel than any before; with the service becoming one of the best-selling and most popular dinnerware sets in America. Only Russel Wright’s American Modern dinnerware surpassed it in popularity and sales. The Tomorrow’s Classic set was in production until 1962, and in 1999 the old plaster molds used for its manufacturing were displayed at an extraordinary exhibition,[7]providing an impetus for the set’s re-production. The precision with which the molds were crafted is exemplary, they themselves have an aesthetic value, and they also reveal that the rigid shapes are the result of the use of a single mold. This feature is perhaps most striking on the body of the teapot and cream jug.

The fourth defining dinnerware set of Zeisel’s oeuvre is the Century service, also designed for the Hall China Company, introduced with perhaps even bolder elements such as petal-shaped plates. However, the commercial success of Tomorrow’s Classic could not be surpassed.

In the 1960s, the American fine ceramics market was flooded with imported products, leaving little for local designers to do. Eva Zeisel’s attention then turned to the foreign market, working from the late 1950s with international companies such as Rosenthal AG of the FRG, Noritake and Nikkon Toki of Japan, and Mancioli of Italy.

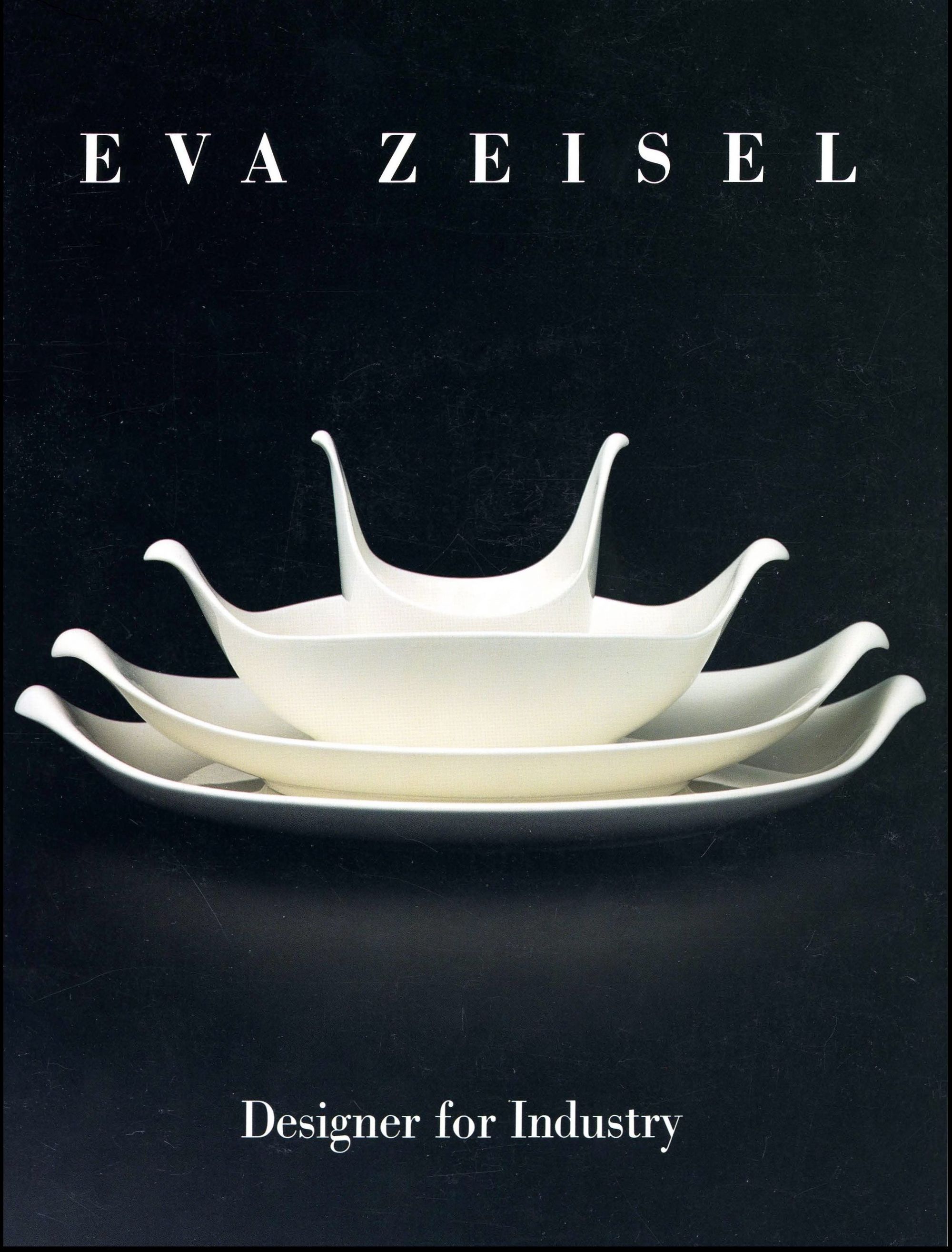

In her chosen home country, Eva Zeisel’s objects were rediscovered in the 1980s. In 1983, while preparing for her retrospective and traveling exhibition, she visited Hungary, where she designed her UFO set again at Kispest, this time at the Granite Grinding Wheel and Stonedish Factory, and created a world-famous series of vases and bonbonnieres using iridescent eosin glazes at the Zsolnay factory in Pécs. The traveling exhibition prompted the publication of perhaps the most detailed monographic analysis of her oeuvre to date in the catalog Eva Zeisel: Designer for Industry.[8]

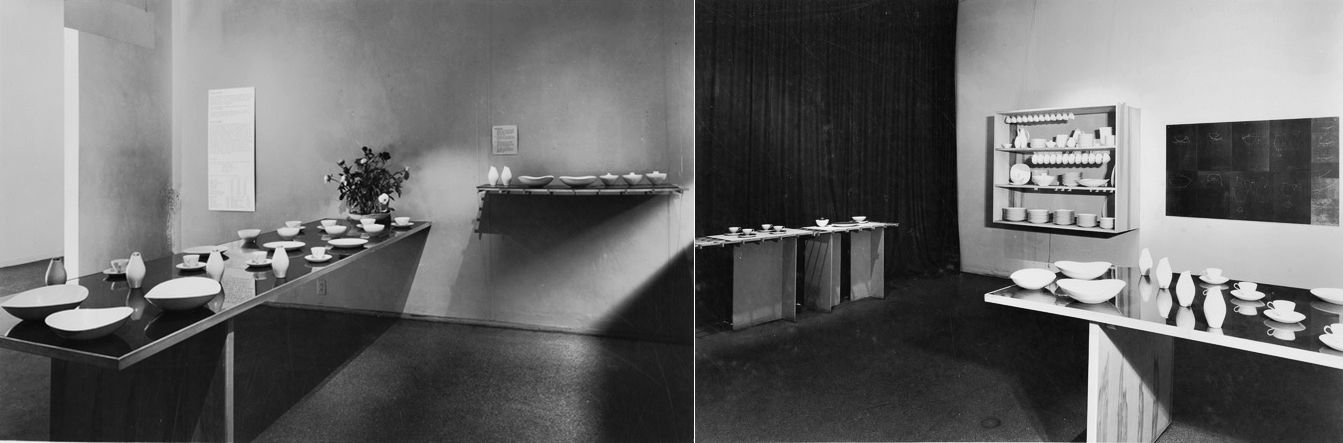

The exhibition was on display at the Museum of Applied Arts from April 17 to May 31, 1987. It was then when the Hungarian public had a chance to get acquainted with Éva Stricker-Zeisel’s name and her impressive oeuvre, for which she was awarded the Order of the Star of the Hungarian People’s Republic by the Presidential Council. The exhibition and installation were designed by Gyula Ernyey and were displayed in the museum’s Glass Hall, with a totally innovative overall image for the time. Zeisel’s four most important sets were not enclosed in glass cubes, but arranged on huge round tables, practically laying them with the pots. The sets were highlighted by the lighting hanging over them, concealed in huge lampshades. With the catalog for the exhibition, Ernyey annotated the first scholarly summary study of the designer published in Hungarian, and his work is therefore still a source of great value today.[9]

Zeisel’s exhibition was opened by the then rector of the Hungarian College of Applied Arts, István Gergely, and the designer visited the college; teaching and inspiring interactions with students have been a lifelong experience for her.

Eva Zeisel visited Budapest again in 2004, when she was awarded the Commander’s Cross of the Order of Merit of the Hungarian Republic and was appointed honorary professor at the Hungarian University of Applied Arts. This time her exhibition was held in the Ponton Gallery of the University from April 2 to 10. On the occasion of the opening, Zeisel—despite her 98 years of age—even gave an improvised consultation to the students of the Department of Silicate Design. The Museum of Applied Arts has acquired a significant collection of Zeisel’s new designs from the University, thus, the collection includes objects of her late works. The painful insight of József Vadas in his reviews published in 1987 and 2004 is the only relevant aspect in the context of the designer’s unabated work, according to which Eva Zeisel—together with many of her Hungarian design colleagues—remained a sabotaged opportunity for the Hungarian fine ceramics industry.[10]

In 2019, the Museum of Applied Arts presented some Zeisel objects from the collection designed for the KleinReid studio at the exhibition entitled “Szubjektív” (Subjective) held in the Guard’s Palace of the Castle Garden. It was a sensitive and dramatic decision on the part of Ágnes Prékopa, the exhibition’s curator, to present the works of the designer, who had a long and legendary career, and the tea set of Orsolya Csirke, a talented ceramicist who died tragically young, side by side in a joint display case. Their objects were linked by the harmony of playful, liberated shapes and rounded forms that invite the touch.

Eva Zeisel died on December 30 2011 at the age of 105; her family is taking care of her legacy. Her daughter Jean Richards shared small, previously unknown details of the designer’s life in two interviews in 2019 and 2020 (see here and here). Her grandchildren have each created a website, one of them a monographic database with interesting facts such as the films and series in which Zeisel objects appear, and the other with the aim of reproducing and distributing the original designs (see here and here).

Eva Zeisel was not only a ceramic designer, but she also worked with other media—glass, plastic, wood, metal, bent steel tubes, textiles—and her style and design attitude were characterized by constant renewal, a creative urge to keep fresh with new impulses. According to Zeisel’s design credo, one of the goals of design is the playful pursuit of beauty, and as an essence, this is reflected by every object she designed.[11]

Notes, references:

[1] For more about Éva Stricker’s ancestors and her youth, see for example: Gabriella VINCZE: Stricker (Zeisel) Éva (1906-2011). Az ipari formatervező, a képzőművész és a mozdulatművész. In Ars Hungarica. 2014. Vol. 40, No. 1, pp. 111-118.

[2] Ödön Faragó reported on the 1926 exhibition (Philadelphia Sesquicentennial Celebration): Ödön FARAGÓ: A Philadelphiai magyar iparművészeti kiállítás. In Magyar Iparművészet. 1926. Vol. 29, No. 6-8, pp. 110-112.

[3] “In the arts and crafts section of the fair, the most eye-catching was the pottery of Éva Stricker. The products of the first Hungarian art pottery factory bear the artistic stamp of the old Hungarian smoke firing. The originality and beauty of the lanterns and grotesque animal figures made in her factory are a testimony to her exceptional artistic talent. Éva Stricker’s work is of pioneering importance in Hungarian craftsmanship, in that while previous craftswomen burned their designs on ready-made pots, she makes the pots herself, with great skill and exquisite taste.” (the Ed.’s article): Ma délelőtt nyílt meg jubiláris ünnepség keretében a Budapesti Nemzetközi Vásár. In Esti Kurir. 1926. (18 April), Vol. 4, No. 87, pp. 4 and 10. [The source of the quote is page 10, highlight in the original.]

[4] In Hamburg she worked as a designer at Hansa Kunstkeramik, later at Schramberger Majolika Fabrik, and in Berlin at Christian Cartens Kommerz.

[5] P.: A lélek kulisszái. In Ujság. 1928. (14 Oct), Vol. 4., No. 234., pp. 18.

[6] András KÖRNER: Zeisel Éva dobogó szíve. In Parallel. 2015. Vol. 32., pp. 4-11.

[7] Lost Molds and Found Dinnerware: Rediscovering Eva Zeisel’s Hallcraft. The International Museum of Ceramic Art, New York State College of Ceramics at Alfred University, Alfred, New York, February 11—September 9, 1999. Curated by Margaret Carney, PhD.

[8] EIDELBERG, Martin—OSTERGARD, Derek—TOHER, Jennifer: Eva Zeisel. Ceramist in an Industrial Age. In Eva Zeisel. Designer for Industry. Montreal—New York: Le Château Dufrense, Musée des Arts Décoratifs de Montréal, Smithsonian Institution Traveling Exhibition Service, 1984. [Exhibition catalog, the referred study was also used as a source for this text.] In 2013, a monograph on the complete oeuvre was published: KIRKHAM, Pat (the Ed.): Eva Zeisel. Life, Design, and Beauty. San Fransisco: Chronicle Books, 2013.

[9] The publication of the catalogue was preceded by an essay by Ernyey in the magazine Művészet: ERNYEY Gyula: Zeisel Éva. A modern amerikai kerámia úttörője. In Művészet. 1986. Vol. 27., No. 1., pp. 53-55. ERNYEY Gyula (study)—GÁSPÁR Zsuzsa (the Ed.): Zeisel Éva. A modern amerikai keramika úttörője. Budapest—New York. Budapest: Museum of Applied Arts, 1987. [Exhibition catalog.]

[10] József VADAS: Megméretünk. In Élet és Irodalom. 1987. (8 May), Vol. 31., No. 12. József VADAS: Mindennapi dizájn. Zeisel Éva. In Kritika. 2004. Vol. 33., No. 9., pp. 16-17.

[11] I would like to thank Hilda Horváth and her colleagues at the Museum of Applied Arts Data Archive for their help in this research. I am grateful for the photos: Krisztina Friedrich, Zsófia Kancler, Ágnes Soltészné Haranghy. Special thanks to Jean Richards and András Körner, Éva Horányi and Dóra Reichart.

Photos:

Photo 3: Éva Stricker: Sugar holder with lid. ( Kispesti Porcelán-, Kőedény- és Kályhagyár Rt., around 1926. Source: Eva Zeisel: Designer for Industry (1984), 16.

Photo 4: Éva Stricker: Tea set, Gobelin painted with 8 patterns. Schramberger Majolik Fabrik, around 1929. Source: National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne.

Photo 5: Éva Stricker: Coffee set, painted in Piet Mondrian style. Schramberger Majolika Fabrik, 1928-1930. Source: British Museum, London.

Photo 6: Éva Stricker: Intourist (Soviet travel agency) tea set, painted with Leningrad 1935 decor. Lomonosov Porcelain Factory, 1933 (design), 1935 (decor plan, ornamentalist: Varvara Petrovna Freze). Source: Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum, New York.

Photo 7: Éva Stricker: Tea set. Dulevo Porcelain Factory, around 1935. Source: Eva Zeisel: Designer for Industry (1984), 25.

Photo 12: Eva Zeisel: Salt and pepper shaker from the Town and Country set. Red Wing Pottery, 1945 (design). Source: Museum of Applied Arts, photos by Krisztina Friedrich

Photo 13: Mother with child (Eva Zeisel and Jean Richards) as an early model of the salt and pepper shaker. From Eva Zeisel, Designer for Industry (1984), 93.

Photo 14: Eva Zeisel: Plate from the Hallcraft/Tomorrow’s Classic set, with Buckingham decoration. Hall China Co., 1949-1950 (design), (decorator: Erik Blegvad). Source: Museum of Applied Arts, photo by Krisztina Friedrich

Photo 15: Eva Zeisel: Hallcraft/Tomorrow’s Classic tea set with Fantasy decoration. Hall China Co., 1949-1950 (design), (decorator: Ross F. Littell). Source: National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne.

Photo 16: Eva Zeisel: Lidded pot from the Hallcraft/Tomorrow’s Classic set, with Dawn decoration. Hall China Co., 1949-1950 (design), (decorator: Charles Seliger). Source: Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum, New York.

Photo 23: Éva Zeisel: Interior of the exhibition called The Pioneer of Modern American Ceramics, Museum of Applied Arts, 1987 Source: Museum of Applied Arts, Data Archive, Technical File 582/43

Photo 24: The Hallcraft/Tomorrow’s Classic dinnerware set in the Museum of Applied Arts, 1987. Source: Museum of Applied Arts, Archives, Technical file 582/32

Photo 25: Objects designed for the Schramberg Majolica Factory in the Museum of Applied Arts, 1987 Source: Museum of Applied Arts, Archives, Technical file 582/24

Photo 26: Objects designed in the Soviet Union in the Museum of Applied Arts, 1987 Source: Museum of Applied Arts, Archives, Technical file 582/25

Photo 28: Eva Zeisel with her eosin glazed objects designed at the Zsolnay factory in 1983, Ponton Gallery, 2004. Source: archive of the Department of Silicate Design (now Design & Art Department), Hungarian University of Applied Arts (now MOME), photo by Talisman Brolin

Photo 29: Eva Zeisel at her chamber exhibition in Budapest, Ponton Gallery, 2004. Source: archives of the Department of Silicate Design (now Design & Art Department), Hungarian University of Applied Arts (now MOME), photo by Talisman Brolin

Photo 30: Eva Zeisel surrounded by students and teachers, Ponton Gallery, 2004 (Back row, from left to right: Dorottya Nagypál, Barnabás Máder, Attila Nemoda, Anita Tóth, Zsolt Budai, Bernadett Kozma, Erika Rejka. In the front row, from left to right: Gyula Mihály, Sándor Stricker, literary historian, Eva Zeisel, Éva Kádasi, head of department.) Source: archive of the Department of Silicate Design (now Design & Art Department) of the Hungarian University of Applied Arts (now MOME), photo by Talisman Brolin

Photo 31: Eva Zeisel and her daughter, Jean Richards, looking at the poster for the Budapest Chamber Exhibition at the entrance to the Ponton Gallery, 2004. Source: archives of the Department of Silicate Design (now Design & Art Department) of the Hungarian University of Applied Arts (now MOME), photo by Talisman Brolin

Cover photo: Eva Zeisel: Pieces from the Hallcraft/Tomorrow’s Classic dinnerware set. Source: Museum of Applied Arts, photo by Krisztina Friedrich

In our Object Fetish series, we tell you about emblematic pieces of domestic object culture. We explore objects and their designers: we ask questions, we investigate, we discover. A bi-monthly edition in the collaboration of Kitti Mayer and Piroska Novák, design theorists.

In partnership with:

Sleeping Beauty’s dream in Ipolytarnóc | Hype X Field of Sparks

Eastern European accessory and bag overview | TOP 5