Citrus yellow portable MINI-VIDI, pastel blue plastic milk carton holder, red leatherette club chairs, pink minyon (Hungarian cream-filled cake—The Transl.) on metal drawer cabinet. These all appear in the show called “The Informant.” Being object-obsessed design theorists, we were immediately sucked in by the film. It was a no-brainer to contact the series’ production designer, who had worked on Ildikó Enyedi’s feature films (“On Body and Soul,” “The Story of My Wife”), the “In Treatment” series and György Pálfi’s “Free fall.” Now her task was to evoke the genuine eighties before the regime change. We will analyze, ask questions, tell stories and show you the furnished sets!

A coming-of-age and a rebellion, but mostly a classic spy story—these are the keywords to describe “The Informant” series. Since its release, the story set in 1985 has been the subject of countless articles, interviews and reviews in the national press: some have been completely caught up in the retro craze, the young actors who prepared for their roles based on their parents’ personal experiences and the filmmakers’ instructions spoke up, and some have condemned the film for its historical inaccuracies. It’s not our place to do justice, but it’s undeniable that “The Informant” has moved half the country, making this emotional era a subject of dialogue and, not least, bringing the unique atmosphere of Central Eastern Europe into living rooms in Hungary and abroad (it was by far the most-watched HBO content for the month of April, ahead of the new Batman).

HBO’s first in-house produced and developed series can be viewed from many different angles: we won’t dive into political-historical or film-critical analysis, but instead, we’ll dive into what we were most interested in as we waited with excitement for the new episode week after week. We asked Imola Láng, who was responsible for the production design, about the planning and the production phase, and how difficult it was to find and furnish authentic locations. Imola also shared a few pages from the “Bible” used for the production and gave us a few behind-the-scenes secrets.

I remember my excitement for the first episode of “The Informant,” and only 20 minutes in, I caught myself focusing on the decoration and props instead of the storyline; the Ultra detergent box, the yellow bread basket on the shelf, the Utasellátó (Hungarian company making products for the catering of rail passengers—The Transl.) cups and plates. I assume, there are but a few series junkies like myself, obsessed with objects, glued to the screen, waiting to identify certain iconic objects (see our “Object Fetish” series co-authored with Piroska Novák, where we have also explored the story of the plastic milk pourer that appears in the series).

I was just as excited to see Imola Láng when we met: I was eager to know every single boring behind-the-scenes detail, such as how the objects in the series are purchased and what is the exact responsibility of a production designer.

“The production designer works closely with the costume designer. For example, in the international co-production of ‘The Story of My Wife,’ we brought a painted piece of wall from each of the apartment sets to the dress rehearsal so that the costume design team could design and try on costumes. Both costume and production design are a big responsibility, and the director is the one who brings the two together. Both divisions have a complex task, and it’s not usually an idyllic situation—because of time constraints—that I sit in on every dress rehearsal or the costume designer comes with us to the field trip. There are meetings where we agree on colors, but mostly we can change things on set and sneak in another red vest if it makes the set more exciting,” Imola begins.

The sets are brought to life by the cinematographer. What the cinematographer shows the audience sees—after the shooting, the sets are dismantled, and there are no second chances, says Imola. „It’s good to be able to consult a lot with the cinematographer during the preparation because we can really help each other. So, in an ideal working relationship, the result is much better if we have an agreed concept and I know what lighting style or camera movement they have in mind. It’s most effective if I can be there for the meetings between the director and the cinematographer. This is especially important in the pre-production phase, so we can work on the same film.”

And how did the production design take place in case of „The Informant?,” I ask because I can only guess at what happens from the first meeting to an unsuspecting HBO user finding the series and hitting PLAY.

“Here, the situation was special in that HBO put out a production design competition: the first thing I got was the script—I really liked it and it sparked my imagination. Each of the visual designers who were invited put together a submission, and they went to HBO and they chose one. I met Bálint (Bálint Szentgyörgyi, the creator of the series—The Ed.) and Viki (Viktória Petrányi, the producer of the series—The Ed.) and presented my application. They mainly showed examples of colors, shapes, moods and took a look at the intended character of the main locations.”

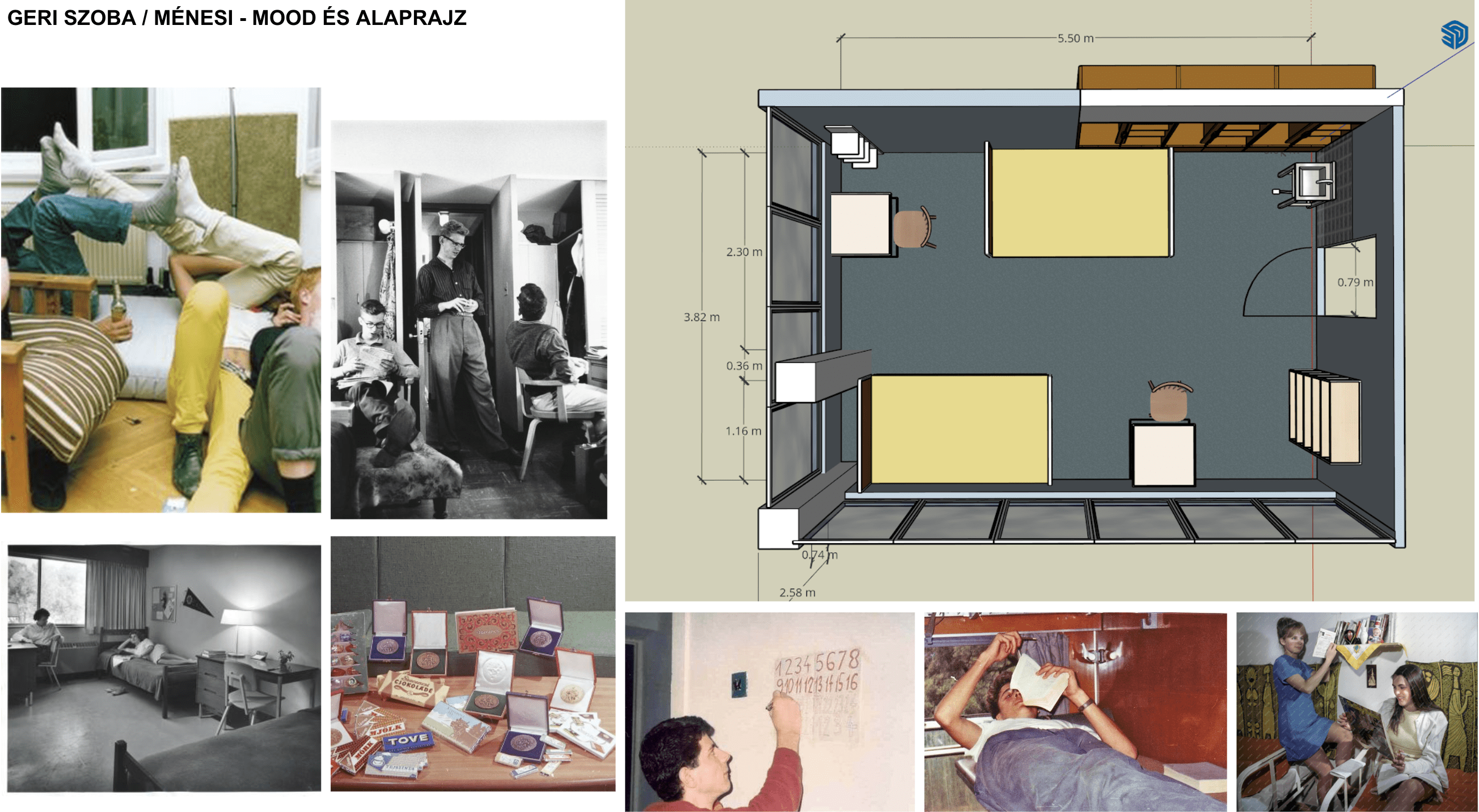

According to Imola, the design process itself, the preparation of the application, took a relatively long time, and by the time the actual work started, she already had a clear idea of what she wanted to see on set. The set designs were created together with Zsófia Tasnádi (supervisor art director of the series—The Ed.).

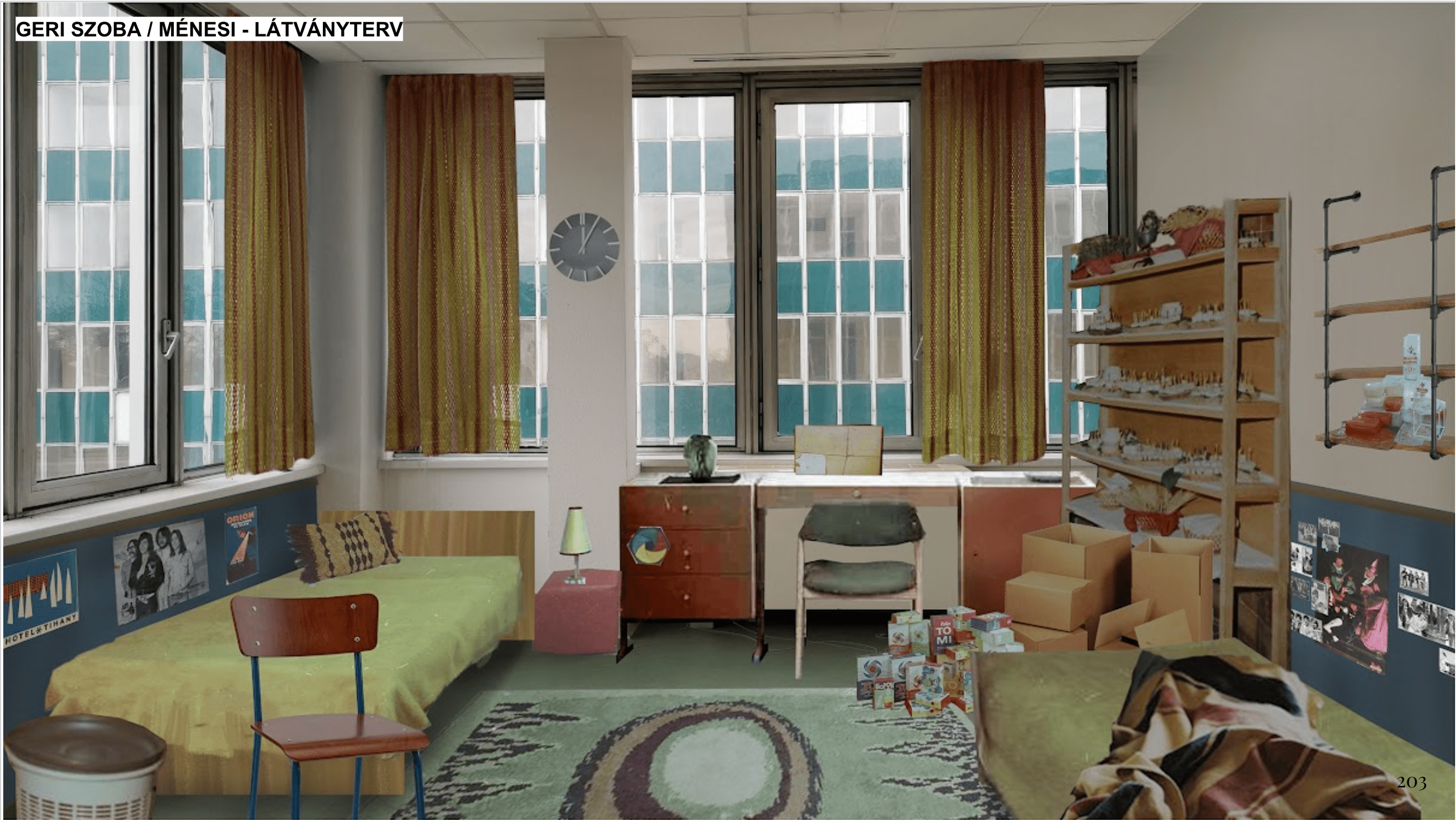

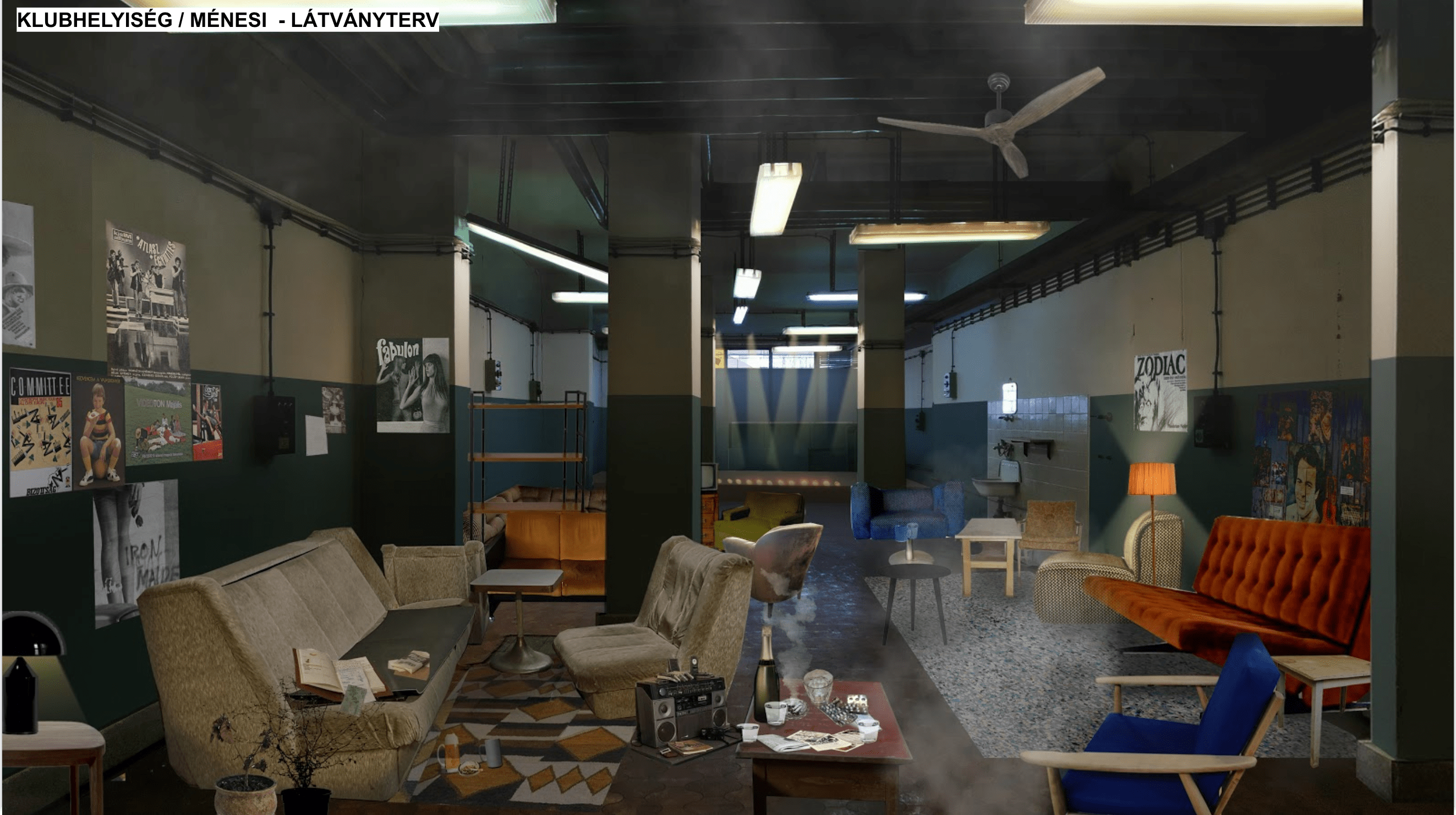

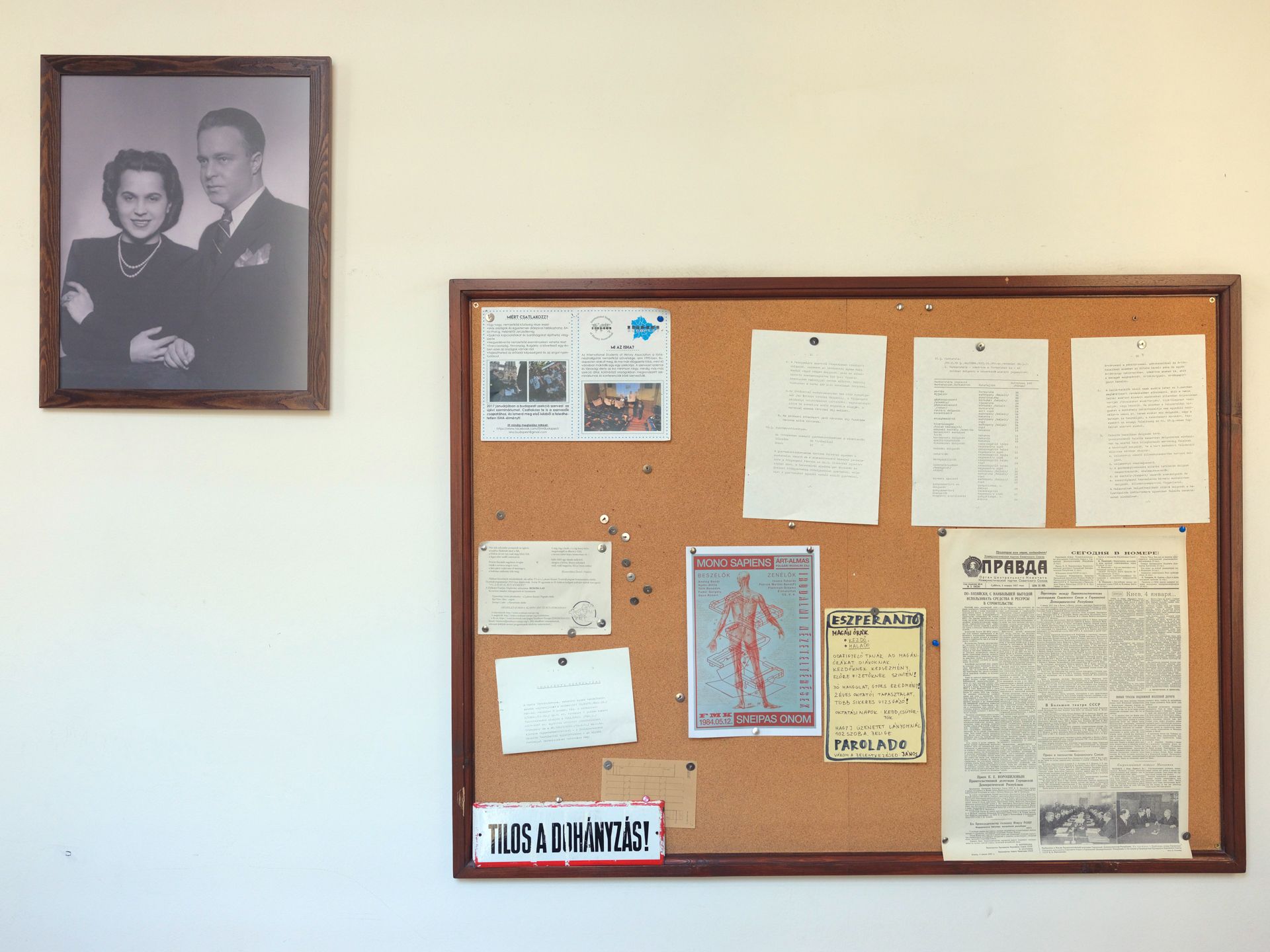

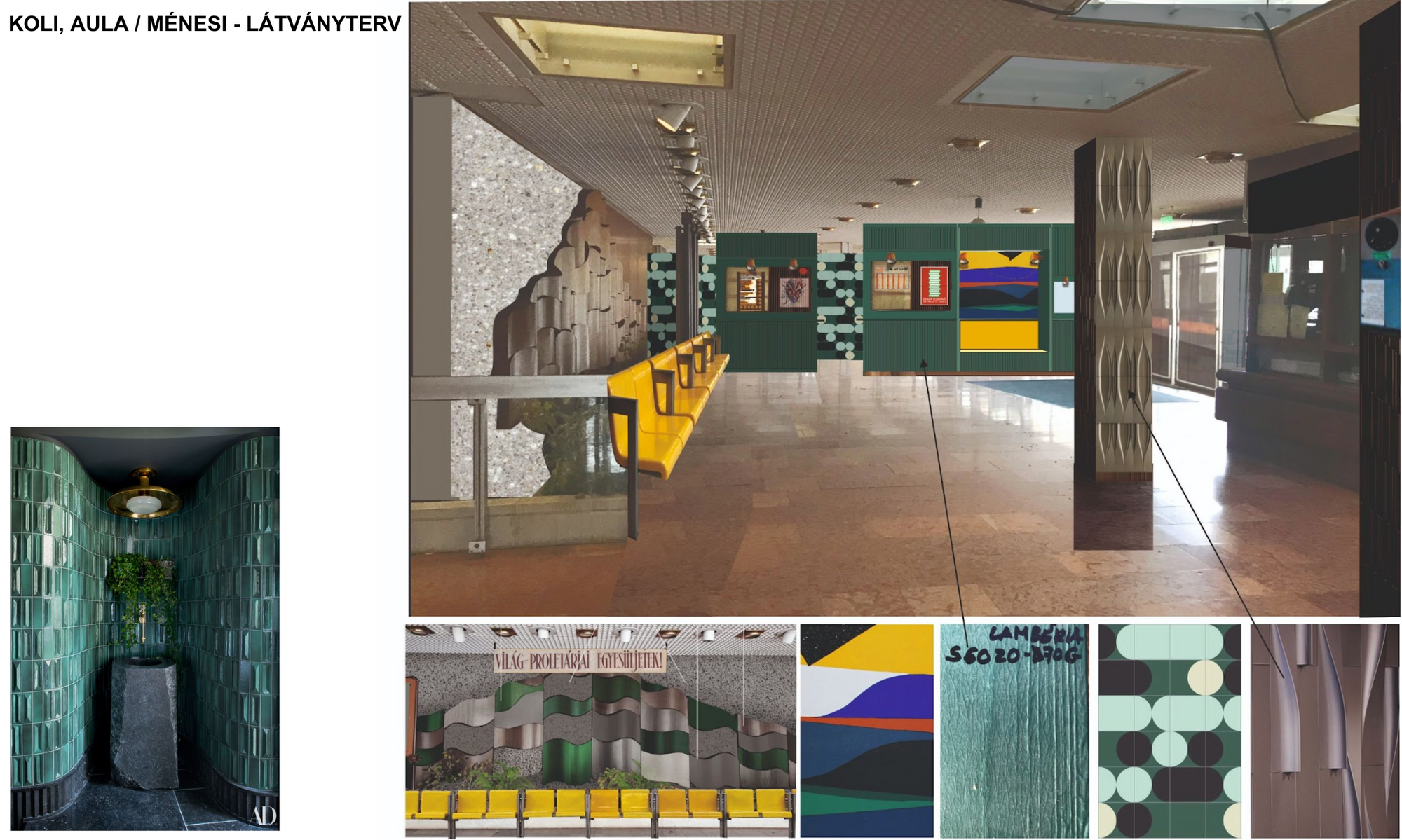

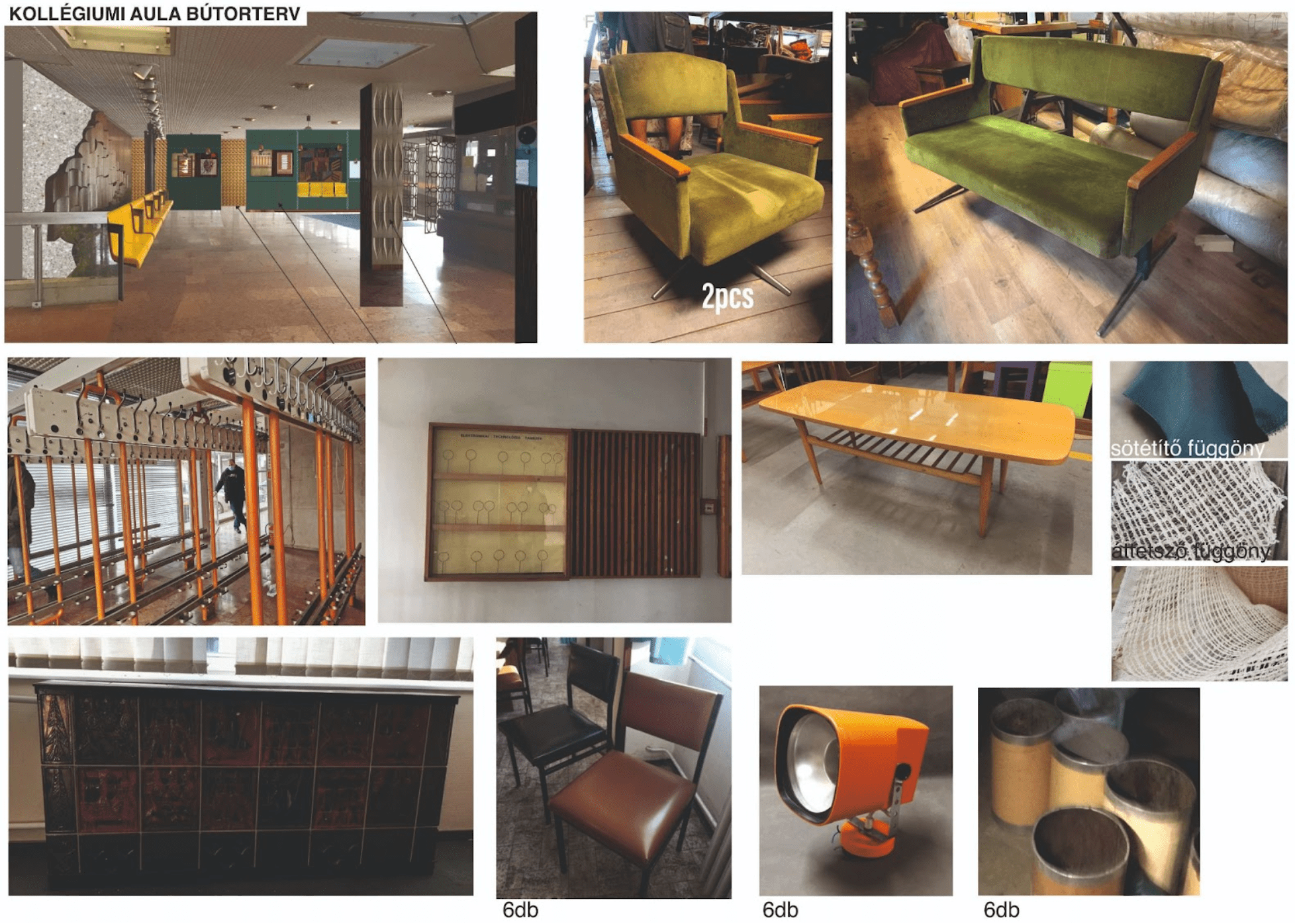

“It’s also special that there were three directors, Bálint was constantly working on scripts. We started producing the set designs and looking for locations. Producer Viki Petrányi put the series together and helped a lot to get the dialogue going between the crew members. She convened a meeting where we decided on the mood of the film: not too retro, not too socio-retro, instead, we tried to ‘elevate’ it a bit, using deliberately enhanced colors. We looked for the focal point of each set, put in something that would evoke the period accurately in the viewer’s mind, and then sewed the coat around it,” says Imola, and then goes on to point out the criticisms of the inaccuracies of the series, such as the fact that the dormitory in “The Informant” looks much better than it did in reality. “That was done on purpose. It was a decision and an expectation on the part of HBO, not to paint a dark Eastern European atmosphere, but to show the energy and drive of the young people with the sets. All the elements we used were true to the era, but we chose the best of everything. We juxtaposed the slightly brighter colors with the slightly more tasteful things. We used furniture from the seventies to furnish the dormitory, but the wall colors, coverings and textiles make the overall effect more harmonious than it was in the eighties.” I am reminded of the country house of the protagonist, Geri Demeter, where I discovered two Gábriel Frigyes chairs in the kitchen. Imola says that one “flashier” piece is not that hard to get, but when you need more of something, “well, you might have to squint a little.”

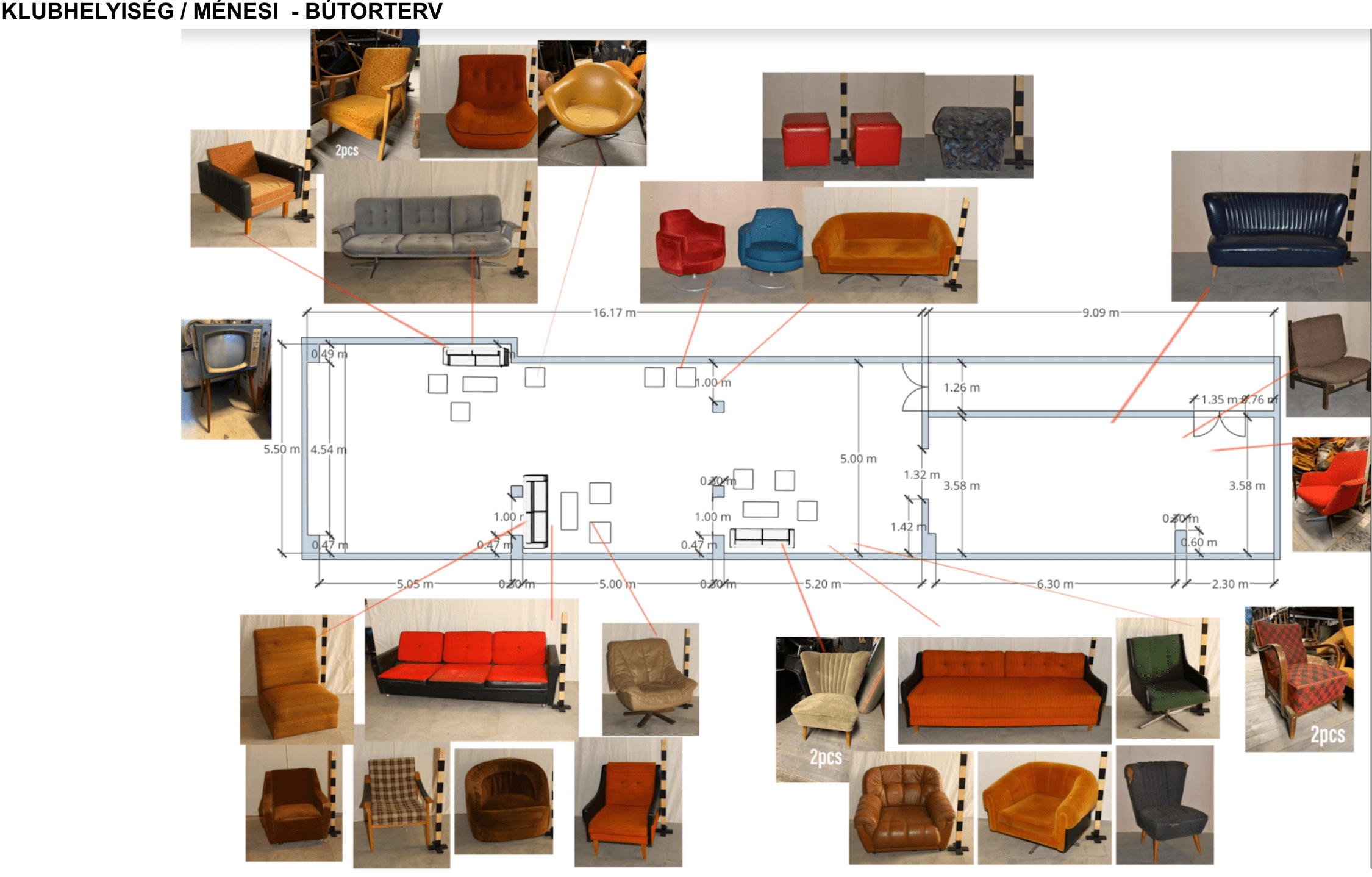

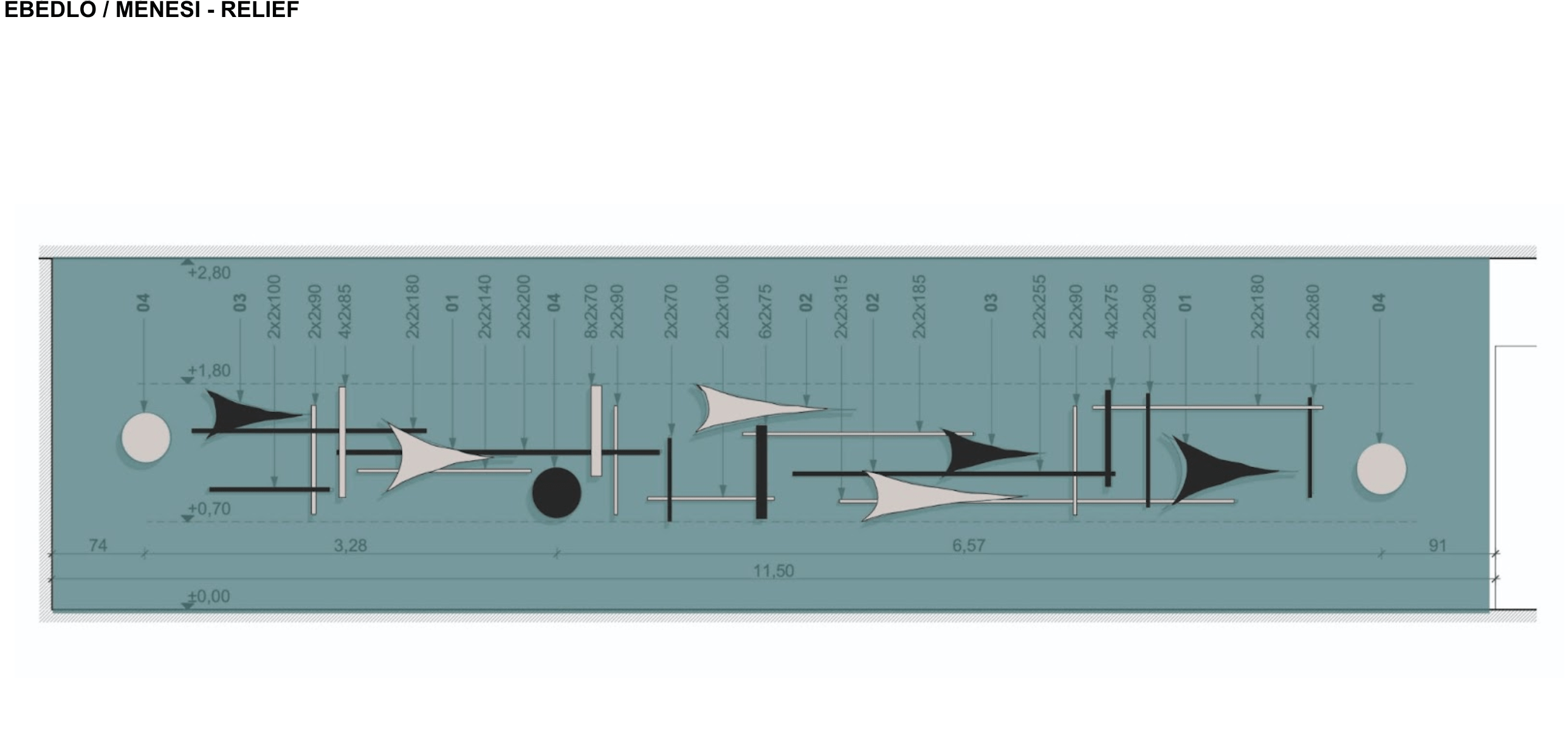

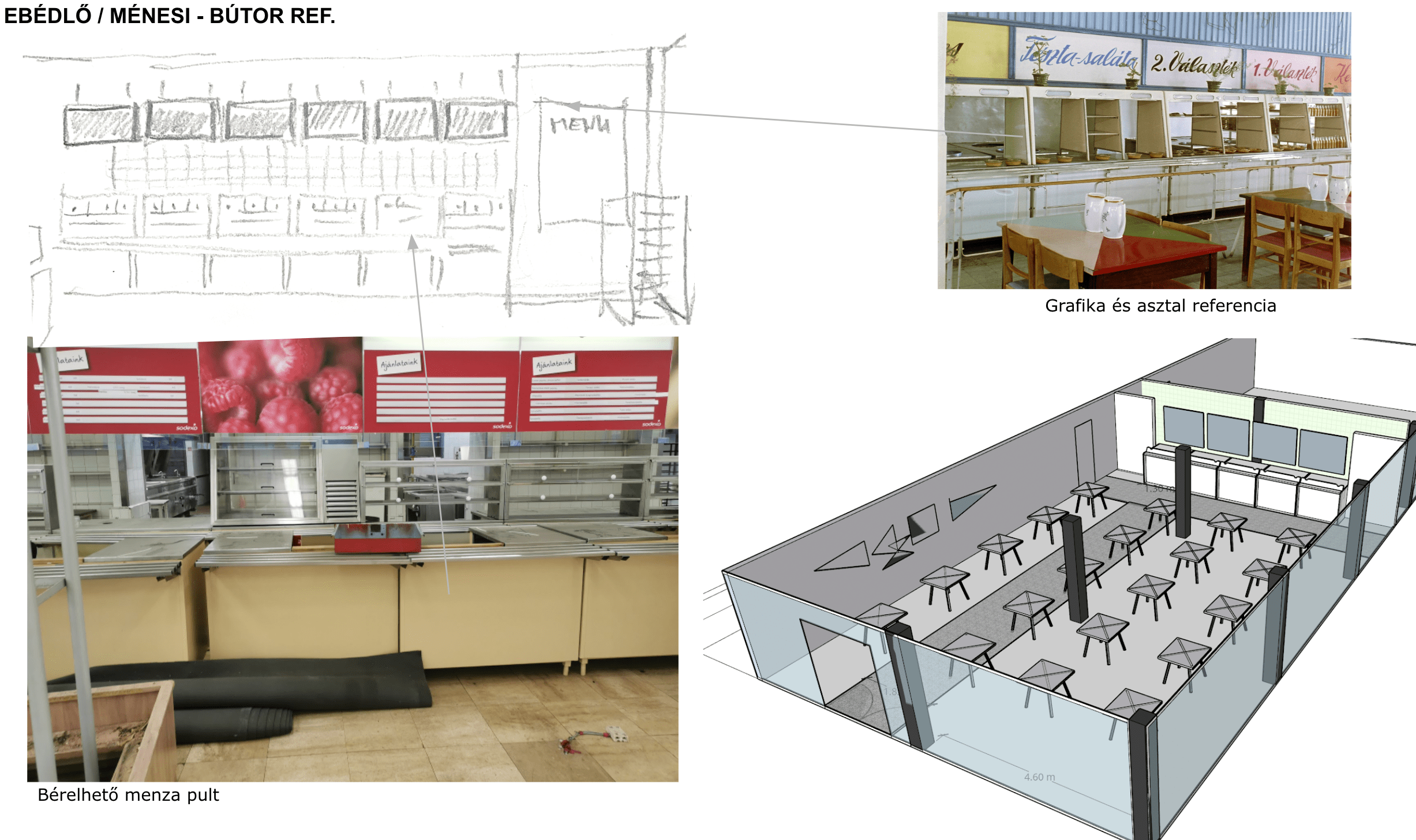

She says they’ve had great luck with the locations: two iconic buildings in the series have since been demolished (the former BME V2 education building, the cafeteria of the Goldmann György Square and the College of Public Administration). “We were given these sites, which were architecturally perfect for us, we just had to take out the elements, colors and materials that didn’t fit, and then we could use them, furnish them with furniture and props, re-tune them. We used these buildings as if they were studios. In the lobby of the College of Public Administration on Ménesi Way (the Kilián Dormitory in the series—The Ed.), we re-modeled the relief, put in fake walls, and fake columns to make the space smaller and narrower. There, we played mainly with turquoise walls, and the yellow chairs were brought from the college swimming pool, for example. If we had to start now, we might have to do a lot of things in a studio, but we wouldn’t have the money.”

As for the color palette: bright colors are important in every scene (yellow, red, blue, green), but Imola and her team have also been careful not to let these shades cancel each other out, but rather to always have a bright and distinctive color in every scene, often very small objects: a yellow sticker, a phone, a pair of scissors. It is also worth noting how the different locations and spaces make us feel: the State Security building in the series (the Ministry of Human Capacities in Arany János Street) has a colder, “heavier” light than the dormitory building, for example, which uses warmer colors, creating a lighter, more cheerful atmosphere.

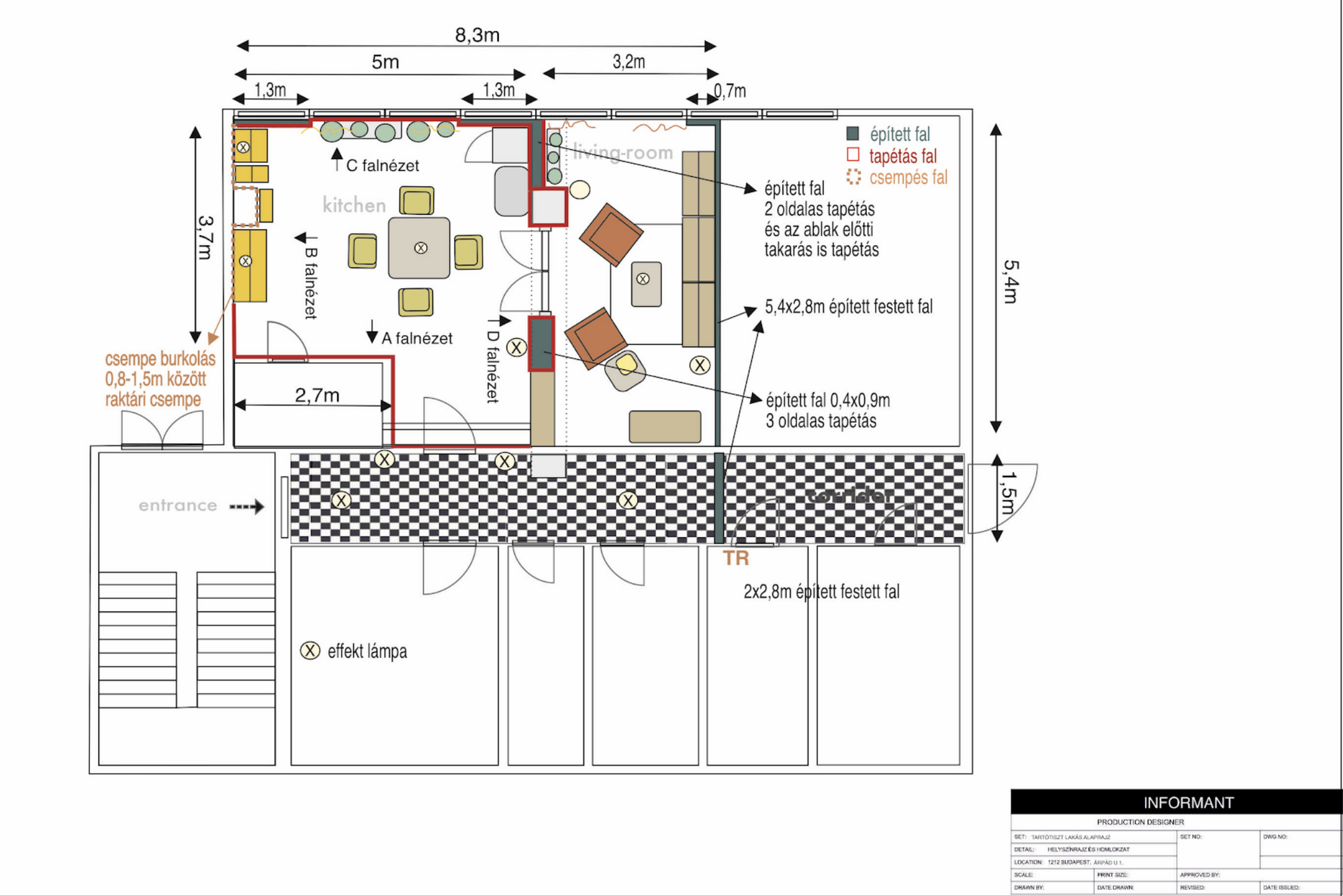

All the scenes in “The Informant” were shot on location, not in a studio. It is interesting to note, for example, that Imre Kiss’ block building apartment was set in a warehouse of a library in Csepel—the layout of the windows seemed ideal, with a corridor and two rooms (a normal housing estate apartment would have been out of the question, as the crew would hardly have fit there). Imola tells us that during the filming, Szabolcs Thuróczy, who plays Lieutenant-Colonel Imre Kiss, jokingly remarked that he thought he (his character) had a bigger apartment than this, with a bigger TV and a newer armchair.

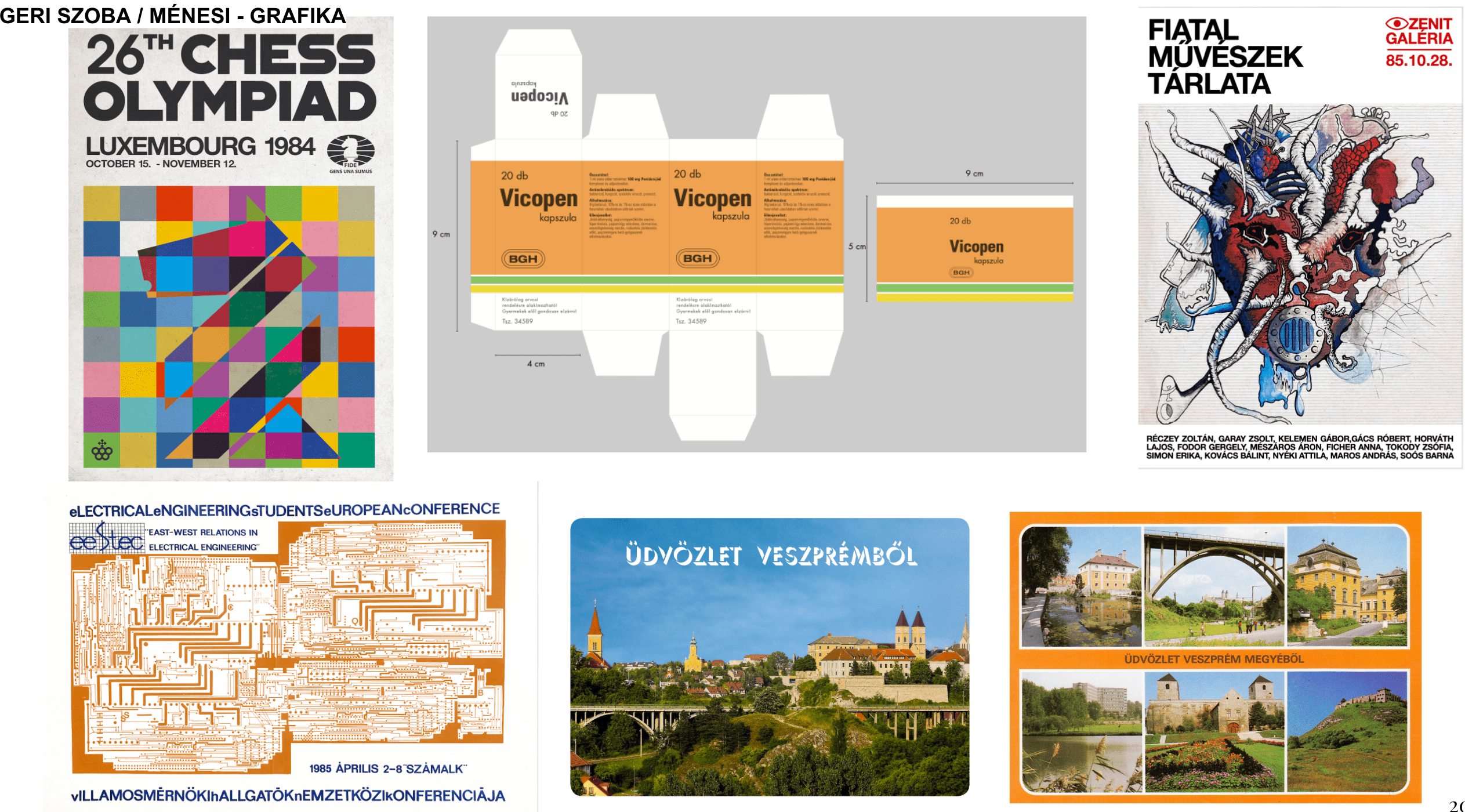

At this point in the conversation, Imola shows me the art department team’s “Bible”—a document of several hundred pages, listing all the sites and all their objects, with photo references. There are scaled floor plans, a collection of pictures, photos taken from the internet or taken by staff, and complete lists of what to get and where to get it. Colleagues are constantly collecting and photographing everything that comes to mind, browsing the image archives and Fortepan. They do a lot of research on what benches and public bins existed in 1985, for example, what the phone box was like, where the graphic designer designed a phone book, for instance. By art department, we mean a team of just a few people (supervisor art director Zsófia Tasnádi, art director Csenge Jóvári, art department coordinator Dorottya Zsiga, graphic designer Zoltán Réczey, draughtsman Dávid Engert, set decorators Gergely Füzesi and Ivett Szász, assistant set decorator Eszter Jankovich, property master Tamás Stadler, assistant property master András Baji, standby constructor Zoltán Takács, special effects supervisor Márton Farkas).

In conclusion, I was wondering which director she would like to work with. “I’m a bit realistic for this, I don’t have a bucket list. I have the advantage of knowing a lot of filmmakers in the industry and I can work very effectively with my colleagues. Sometimes I try to imagine working in another country, but I still see myself as a really weak hologram. In fact, the whole filmmaking process may be more ambitious and exciting abroad, but I can only imagine the pace and the teamwork in a friendly, collegial situation,’ Imola admits frankly, because if anything, filmmaking is a team effort.

Photos: HBO / The Orbital Strangers Project

Imola Láng (sections of the “Bible” of the department)

HBO Max Hungary | Web | Facebook | Instagram

Baby shop for the whole family—ODU Store opens its doors

The engineers and the central bank of the future | Interview with Péter Fáykiss and Gábor Magyar, Ph.D.