Georgia is a little Christian country in the heart of the Caucasus surrounded by enemies, mostly Muslims, who does not allow us to have the independence and abundance—interview with Nino Kotolashvili, a Georgian historian.

In the post-Soviet countries, it is often difficult to interpret history, to explore its narratives—even more difficult to build a national consensus on the events of history. In Georgia's case, what are the national compromises on history?

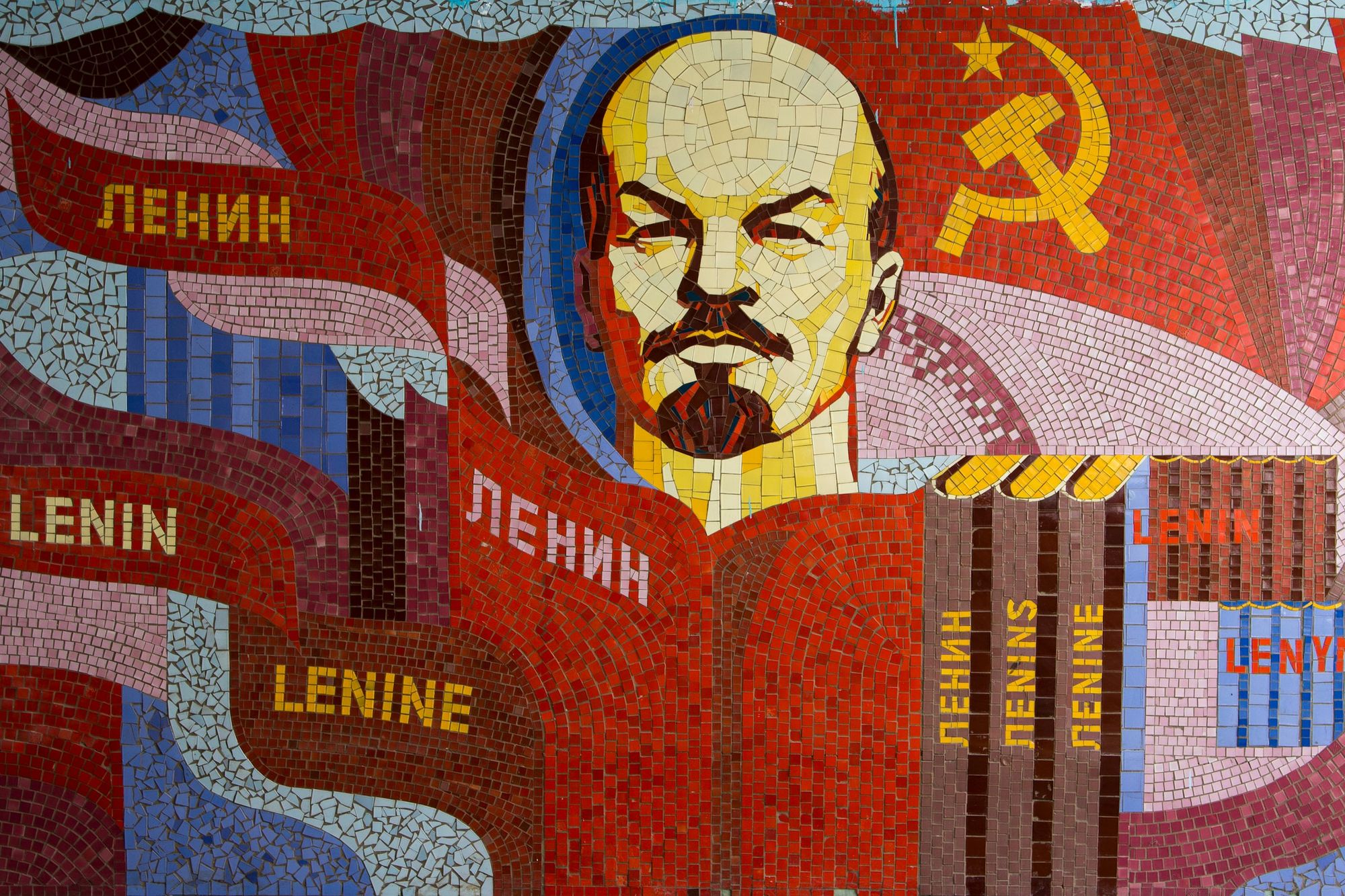

Once Vladimir Putin mentioned that the collapse of the USSR was the hugest geopolitical catastrophe and, at some point, I agree. The dissolution of the Soviet Union all of the sudden revealed the massive problems that has grown up and developed inside the regime for 70 years. “Communal apartment” of the Soviet Union hold and kept the union of 14 Republics, including artificially created autonomous unites within these republics. The territorial and ethnic conflicts existed even before the USSR would be created. Although, to solve those problems the Bolshevik regime, despite its anti-nationalist Marxist ideology, created strange national policies, which included creation of national historiography for each Soviet Republic.

The problem with the Soviet historiography is that first of all, it was ideologized with Marxism-Leninism and secondly, it avoided recent modern history. Because of that only ancient and middle age Georgian history was properly researched and taught, but still without modern context, it made Georgian history half-mythical and mysterious. The Georgian historiography had excessive focus on Georgia, almost like Georgia and the Georgian ethnic group were developing on a separated island and there you are not able to see the context of general processes in the world affecting Georgia and Georgian people. Finally, the historiography was really focused on ethnic-genesis of each ethnic group – that was the soviet vision of nationalism and how they would deal with national issues. Later it caused ethnic fragmentation, instead of integration. The ethnicity was marked in citizenship passports also, for example: Georgian, Abkhazian, Ossetian, Armenian, etc. It means, that citizens living in the Soviet Georgian Republic would not have just Georgian passports, but in their passports their ethnicities were marked. Such ethnic policy developed ethnic nationalism instead of civil nationalism. Thus, soviet historiography was deeply ideologized, ethnized and fragmented from modern history processes.

Today in Georgia because of the past experience it is hard to find national consensus about historical narratives. As a junior researcher, I only can tell that from history Georgians compromise only about two things. One is the Georgian Orthodox Church – Georgians recognize the Orthodox Church and the Christianity as the main factor of national survival in the context of massive Muslim invasions and influences in the region. Secondly, we agree that in the 20th century Georgia was occupied by the Bolshevik Russia and that is the main reason why we restored the Georgian state in 1991. And generally, the nation’s self-vision is developed on the Victimhood – Georgia is a little Christian country in the heart of the Caucasus surrounded by enemies, mostly Muslims, who does not allow us to have the independence and abundance. Later, this victim’s status is reflected how now we deal with our soviet legacy (I will discuss it below). The most difficult part of our history is our recent history from 1991, since Georgia restored independence. Here occurred several conflicts, civil war for Tbilisi, which was caused by political polarization, war in South Ossetia and war in Abkhazia, finally war in 2008 with Russia. On those conflicts and political events, it is not clear where we agree as nation.

In fact, Georgia was given the opportunity to establish a modern nation state twice. Firstly, in 1918, when Georgian Social-Democrats established the first Georgian Democratic Republic, which was occupied by Russia’s Red Army in February of 24th in 1921. On March of 16th Georgia’s legitimate government escaped to France. In 1922 it became part of the Soviet Union through the Transcaucasian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic, which also included Armenia and Azerbaijan. Georgia became independent only after 70 years of occupation, in 1991. Back then Georgia as nation-state had only 3-years independence experience, which ended up with occupation. It means that for almost a century Georgia was distracted from outside the world, not only physically, but mentally. Several generations were grown up in the Bolshevik propaganda, learning soviet Georgian historiography, which finally undermined healthy public discussions about history and it changed the social memory of the Georgian nation. And secondly, Georgian people established an independent nation-state in 1991, which is the longest independence period for modern Georgia. We are still in the process of state building and we need new narratives about history and our identity.

Today, we as a society lack critical thinking about what is going on in the world or in our region. Historical discourse of Georgian society about analyzing ongoing events is still coming from medieval context of Georgia, when Georgia’s main enemies were Muslims and when Christianity was the only identity marker. Best examples are the attitude towards Turkey and Azerbaijan, which are main strategic partners for Georgia today in the region. It is in Russia’s interests to change Georgia’s relationship with the two countries, which in medieval past indeed were enemies, but today are strategic partners. Because of Soviet historiography, which promoted medieval discourse of national memory about Muslims, today many Georgians are sensitive towards Russian informational war campaigns about Turkey and Azerbaijan. The most famous one about Turkey is the Treaty of Kars, signed in 1921: Russian propaganda in Georgia often manipulates that this treaty is overdue and Turkey will take the Adjara region, with Batumi. And about Azerbaijan, 2 years ago there was a huge political scandal, which was propagated by the ruling party to win the 2020 parliamentary elections. The borders with Azerbaijan are part of negotiations and there is a special commission, which should define the boarders and it’s still a process. The ruling party, being aware of medieval Georgian national consciousness, started the propaganda about one of the territories between Georgia and Azerbaijan – Gareji, that this territory was sold by former president of Georgia Mikheil Saakashvili to Azerbaijan. Two scientists who were in the boarder commission were arrested and right after the elections, when the ruling party won the elections, they were released.

Therefore, it’s hard to have national consensus about the history of Georgia. We agree on few things and hopefully, one of the things is that Georgia was forcefully occupied by the Russian Red Army in 1921, which gives clear legitimacy of the Georgian state today to strive towards a European future. And making new historical narratives, which will have national consensus, is in the hands of the young generations. Our generation on one hand should create new narratives, but on the other hand, we should work on community levels to spread and share the narratives and achieve national consensus.

What are the difficulties in coming to terms with the post-Soviet legacy?

Since Georgia became independent in 1991, political and social instability took place. Since then, there are many difficulties, like poverty and corruption, rise of criminal authorities, political polarization and instability, ethnic conflicts, hybrid-democracy and the lack of rule of law and the most important – weak civil society and soviet Nomenklatura in political and economic elites. Here I want to focus more about elite and civil society, however the other problems are mostly connected to that.

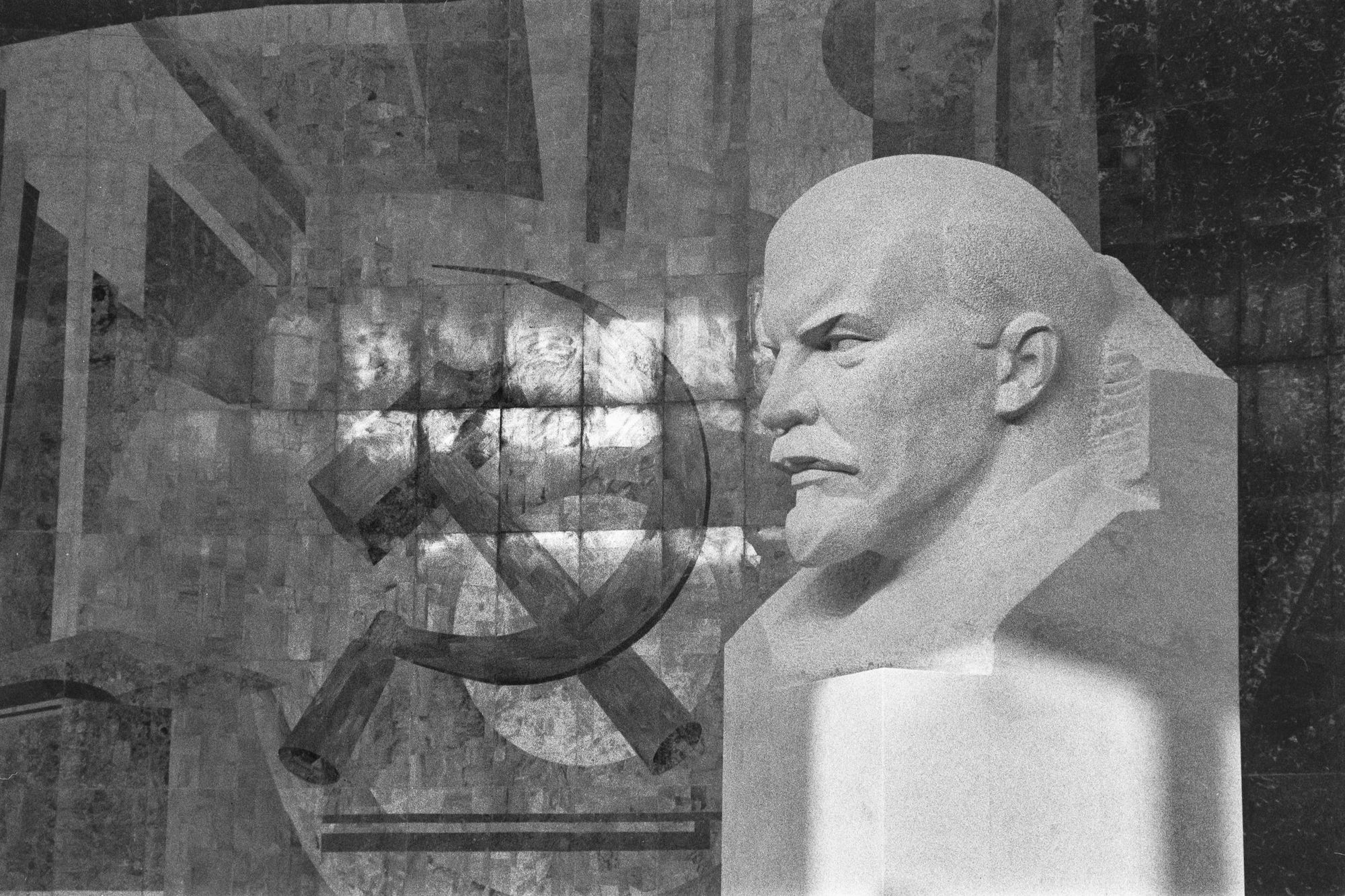

In the Soviet Union everything was centralized and controlled by the party, it was total control of each sphere of human life. Additionally, secret police - “Cheka”, NKVD, KGB (the same institution, with different names in different periods) controlled human behavior and if it was against the Bolshevik regime's standards, they would kill or deport citizens. The centralized ruling-system, with secret police fully destroyed independent civil society organizations and even more – trust between citizens. Weak civil society is also a side-effect of the cult of a strong leader – Stalin. Weak civil society, which is not able to solve problems itself, seeks for a strong charismatic leader, who would save the whole nation. It is directly translated in the political processes after Georgia’s independence. First of all, in 1991 President Zviad Gamsakhurdia was elected as the first president of Georgia, he seemed charismatic and a strong leader, but his political power was equal to an authoritarian leader’s power, which created institutional vacuum for political dialog with opposition. His presidency was marked with inner conflicts, which fatally ended up with his death. Authoritarian tendencies continues to current days and the problem is the same – weak civil society, institutional vacuum for political dialog and executive power monopoly in hands of one leader. Usually, political power is not shared among different parties and all the three branches are controlled by one party, which itself is controlled by one political figure. It is quite similar to the Soviet political regime, which has underwater currencies like oppression of free media and civil society.

The direct soviet legacy is the soviet elite in Georgian politics and economics, which gives them the powerful political tools to stay in power and do not change the political system. In fact, when in 1989 the Czech Republic became independent, they cut all institutional and elite connections to the soviet past and started the massive revision of the past. In Georgia such thing did not happened, Georgia only separated from the Soviet Union, which was almost near to collapse. And here we come to the most painful part of soviet legacy – history, which apparently, was dangerous for the ruling elites. Even after 31 years, Georgia has not got the law of lustration, in order to reveal all criminals and those people, who worked for the Soviet Union and KGB. And there exists the law of 75 years of personal information protection, which allows the National Archives to hide the most interesting parts of our modern history. There are some documents hidden about religious affairs in Soviet Georgia, because again it is in the best interests of the current elites. Since our independence, with lack of political legitimacy Georgian politicians started collaboration with the Orthodox church, which had high legitimacy between citizens. It was and still is a tool to maintain or gain power for Georgian politicians and of course, they won’t reveal all the darkness of the current Orthodox Church in Georgia, which also is continuation of soviet Orthodox Church. There is even a joke that the only soviet institution in Georgia that survives after the collapse of the Soviet Union is the Georgian Orthodox Church.

Stalin was born in the town of Gori and his memory is still preserved in a museum. What reforms had to be made to the museum's exhibition?

Ioseb Jughashvili, later called Stalin, was born in a Georgian provincial city, Gori. From 1936-1937 when Stalin started consolidation of his power in USSR, in the city of Gori his house gained importance, where annual celebrations were planned of Stalin’s childhood and heroic revolutionary past of the great leader. Later around his childhood home-house, which is memorial house, there started building museum of Stalin. Thus, the history of building Stalin’s museum is closely connected to the consolidation of Stalin’s authoritarian power in USSR. Museum itself with full exposition was finished and opened in 1955, after 2 years of his death. Simply, the Stalin’s museum embodies the conception of Stalin’s authoritarian rule. The museum exhibition has not been changed since 1955. Thus, the museum itself reflects the cult of Stalin and still remains as a living memory place of authoritarianism, where Stalin is represented according to the Soviet official propaganda. In this museum Stalin, and his personal history, which also is the Soviet history, is crystallized in time, if nothing has been changed. The current conception of museum shows few things – 1. Georgia as a state has no direct and coherent memory politics, 2. In Georgian social memory Stalin has positive meaning and often meaning of Stalin becomes part of national identity pride.

These two things show the collapse of Georgia in creating historical narrative about Stalin and Soviet past. If for the next 10 years this museum will remain the same, Stalin forever will be crystallized in Georgian historical memory with positive meaning. That is because when you enter the museum you don’t see him as a serial killer, who was in charge of mass purges.

The museum must be reformed into a memorial museum of Stalin’s victims, which will show in full colors the repressions and purges of Stalin. Modern technologies give us the tools to show such purges and repressions in museums in interesting and memorable ways. With exhibition about repressions, purges and victims the story of museum will change – now if we see heroic and good leader, then we will be able to see the dark sides of his politics and personality. In long term reforming the museum will be beneficial to achieve national consensus about Soviet past and will improve democratic shift.

Nino Kotolashvili is a junior researcher at the Soviet Past Research Laboratory, Master's student of Modern Georgian History at Ilia State University. She has worked for an NGO as a project manager for two years. She is currently working on research about purges in the Writers Union in Soviet Georgia and besides, she is a research assistant on a book project "Soviet Georgian History 1921-1991."

Artistic fragility at the front line | Sofika Ceramics

Budapest through the eyes of artists | TOP 5