If one thing really needs to be designed to be inclusive, it is the public toilet—used by old, young, healthy, disabled, the passing businessman, and the homeless alike. At least could use it, if there would be one, but city dwellers are struggling with the lack of free public toilets all over the world. Tokyo seems to be leading the way for city leaders, architects, and designers: stunning public restrooms designed by star architects have spread all over the Shibuja district. Toilet conditions and the role of design in the Tokyo Toilet Project.

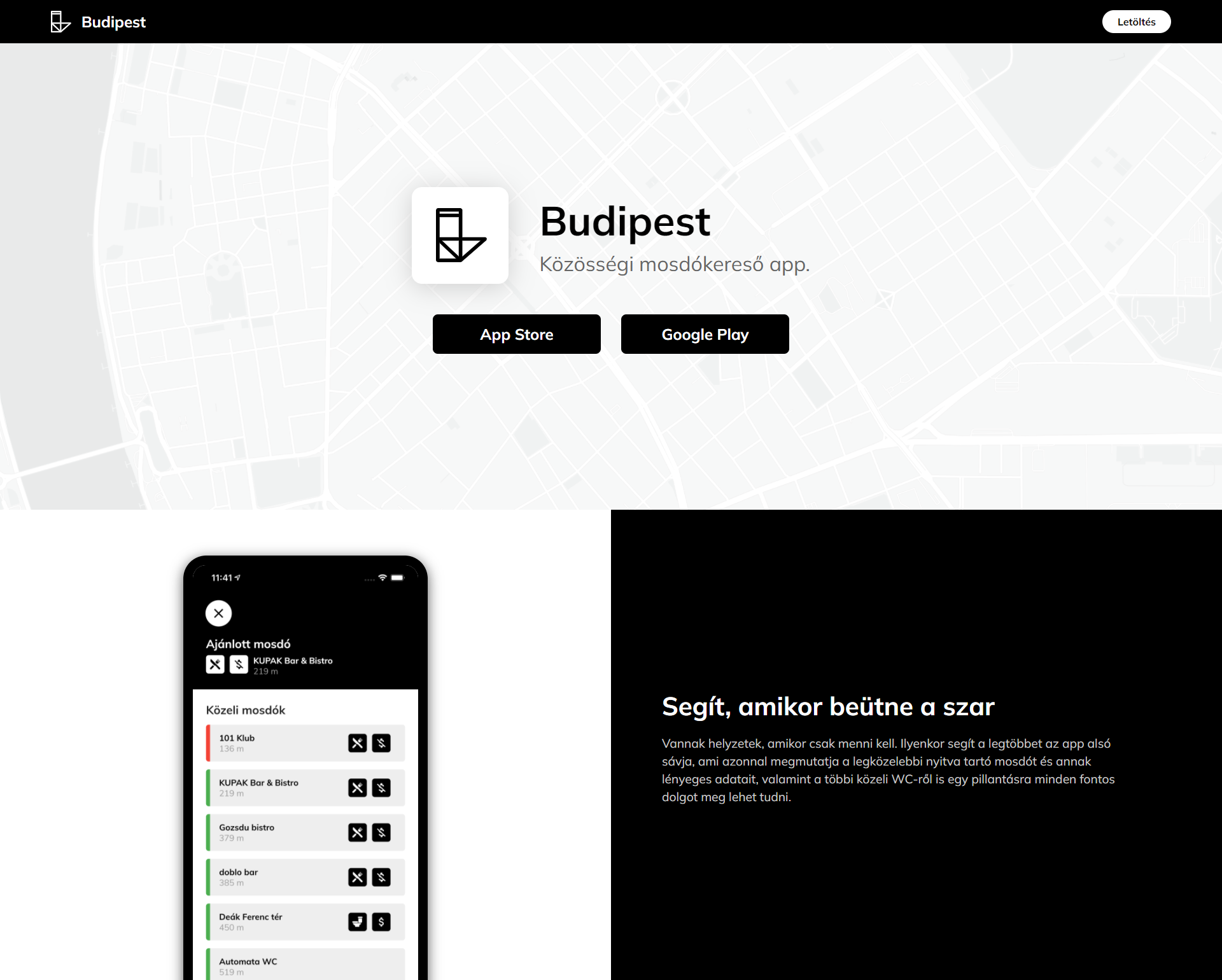

At the end of this summer, we were a little more cautious about choosing Lake Balaton for splashing around, after a series of reports came to light about the increasing phosphorus levels in the lake, which may have something to do with the fact that people—in the absence of free public toilets—use the lake to relieve themselves. The problem has long reared its head not only in this area but in most big cities, including the capital. The cityscape, the complaining comments on social media, and our own experiences confirm that there are not enough public spaces in Budapest either. Although we have not yet seen a large-scale initiative by the city government to address the problem, alternative solutions appear from time to time. One example is the Budipest community toilet finder application, which provides a map of all public toilets in the capital, as well as public buildings and restaurants where we can turn to when we are in need. Users of the app can edit the map themselves, add new places, complement it with important information (such as whether the toilets are free or pay), share their comments. Budipest, while excellent as a quick solution, will not fix the problem.

The public toilet shortage is far from new, let alone unique—from the United States to the United Kingdom, the problem has been made all the worse by public buildings being closed during the pandemic.

According to journalist Alex Brown, “the lack of restrooms has become an issue for delivery workers, taxi and ride-hailing drivers and others who make their living outside of a fixed office building. For the city’s homeless, it’s part of an ongoing problem that preceded covid-19.” While Brown’s comments are specific to the city of Seattle, the situation is no stranger to other major cities around the world.

More public toilets, more vibrant city life

But why are public toilets so important in cities? As well as preventing the spread of infections, there is another good reason:

“Public toilets are essential for creating accessible, sustainable and equal cities, and that they are a vital factor in getting people out of their cars and back to walking, cycling and using public transport,” writes Clara Greed in her book Inclusive Urban Design: Public Toilets, adding that shopping centers have already recognized that if they have sophisticated and well-maintained toilets, shoppers will not go home to do their business and will be more willing to spend more time in shopping complexes.

Public toilets in public buildings, however, don’t solve the problem, as they don’t ensure full accessibility: they don’t accommodate all social groups, and their use is linked to the opening hours of the facilities. And in the case of the few truly public toilets, poor conditions due to lack of maintenance and cleaning, as well as poor placement, undermine the overall image of public restrooms.

Public toilets are not a luxury but a necessity, and architects, designers, property owners, operators, municipal leaders, and government actors are all essential in addressing the shortage. As early as 2003, Clara Greed argued that visions of future cities should place public toilets at least as prominently as modern skyscrapers rather than in hidden corners where they are more vulnerable to vandalism. Tokyo seems to have taken Greed’s words seriously.

Feast your eyes on Tokyo!

How can we improve the stereotype that toilets can only be dirty, smelly, and dark? The Nippon Foundation, a non-profit foundation, has teamed up with the Shibuya Municipality to launch the Tokyo Toilet project to improve the image of public toilets, although it’s hard to imagine that this would be much of a problem for a country that is a world leader in hygiene and toilet culture. Yet, the city has decided to turn ordinary public toilets into local architectural landmarks. Seventeen public restrooms in the Sibuja district were designed as part of Tokyo Toilet, with the help of star designers such as Toyo Ito, Nigo, Marc Newson, and Sou Fujimoto, who was also responsible for the design of the House of Hungarian Music. Twelve of the seventeen toilets have been completed so far. All are accessible, and some are designed to be comfortable for people with stomas.

Each toilet is endowed with ultramodern equipment and unique design solutions, which are remarkable not only in appearance but also in function, at times even divisive. Perhaps the biggest media sensation was triggered by the colorful translucent glass-bordered restrooms designed by architect Shigeru Ban, whose walls darken when someone closes the door from inside. (The glass wall is reminiscent of an earlier Fujimoto project, in which the architect designed a glass-walled public toilet in a walled garden space.) According to Ban, this solution sends a clear message to passers-by that the toilet is empty and clean, so they can enter with confidence. Also born is a touch-free solution by the Disruption Lab Team and Kazoo Sato, called Hi Toilet, where you hardly need to touch anything; most things are voice-activated, which is particularly beneficial given the new hygiene standards that have emerged during the pandemic. The toilets are equipped with models of the TOTO brand, known as the Toyota of toilets.

Different solutions for men, women, children, the elderly, and people with physical disabilities can make a toilet facility more usable and comfortable, and, with the accelerating globalization of the world, cultural differences in toilet use have also become an aspect of design over the past decade. In Tokyo Toilet’s restrooms, pictograms indicate the toilet’s facilities, for example, how suitable it is for elderly people, pregnant women, or people with small children. Tokyo Toilet was not only responsible for erecting the spectacular buildings but also developed a solid operating model for maintaining them. The toilets are cleaned three times a day, and they also undergo a major cleaning every month and comprehensive maintenance every year. A monthly maintenance meeting is held to discuss observations and improvements.

But can the Tokyo Toilet project be transposed to other cultural contexts? Wouldn’t a hypermodern toilet be alienating for those who need it most? Could American, Hungarian, or even Mexican society pay as much attention to maintaining such toilets as the Japanese do? Even if it is not a one-size-fits-all initiative, or even if it is challenging to integrate, the spirit of the Tokyo Toilet—that advanced design can serve the common good rather than a narrow public—could certainly be an example for city leaders, architects, and designers to follow.

Tokyo Toilet | Web | Instagram

The Nippon Foundation | Web | Facebook | Instagram

The Vintage Photo Festival is being held in Poland for the seventh time

“Jewelry hides secrets to be deciphered” | Interview with Anna Börcsök