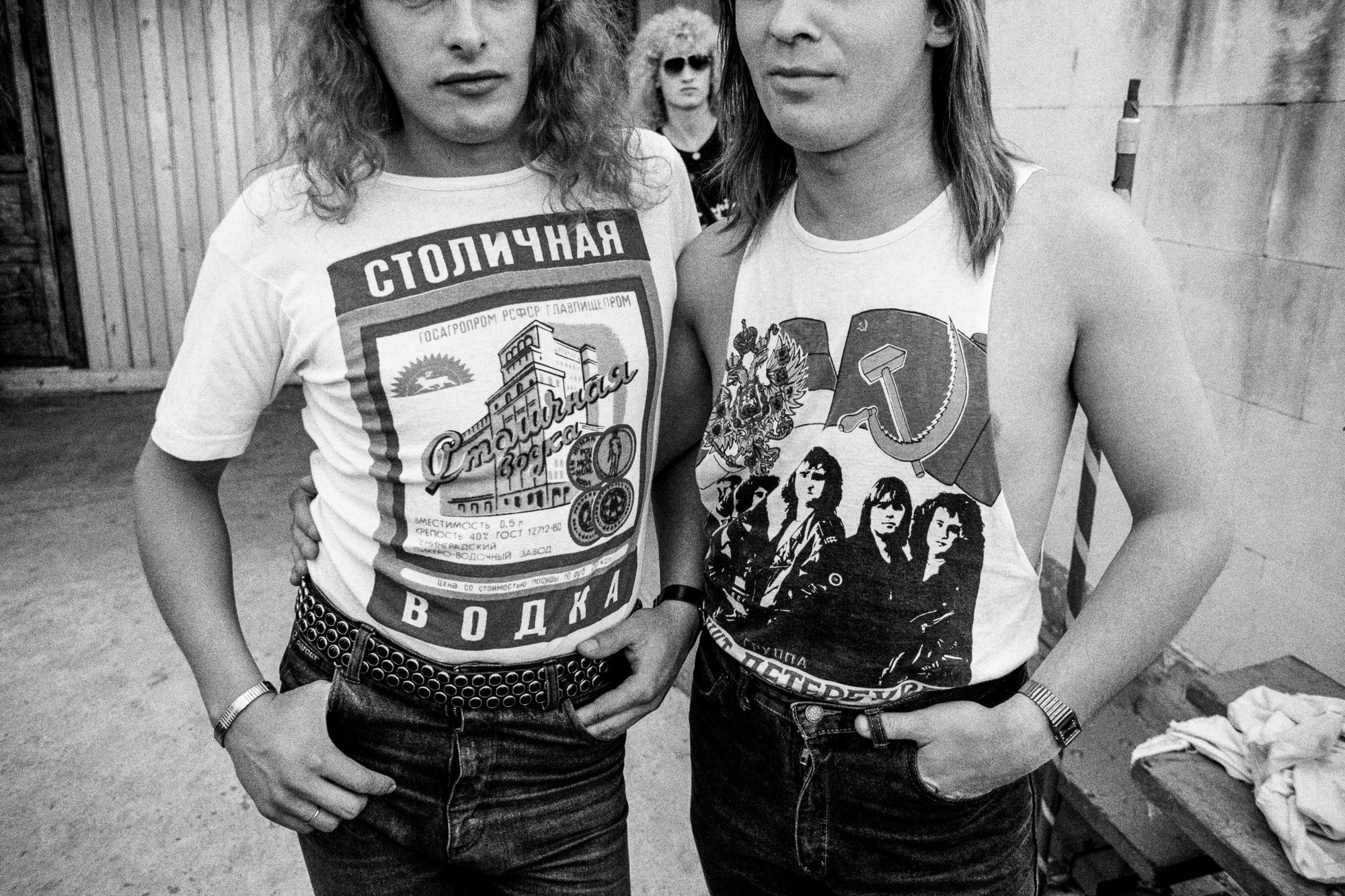

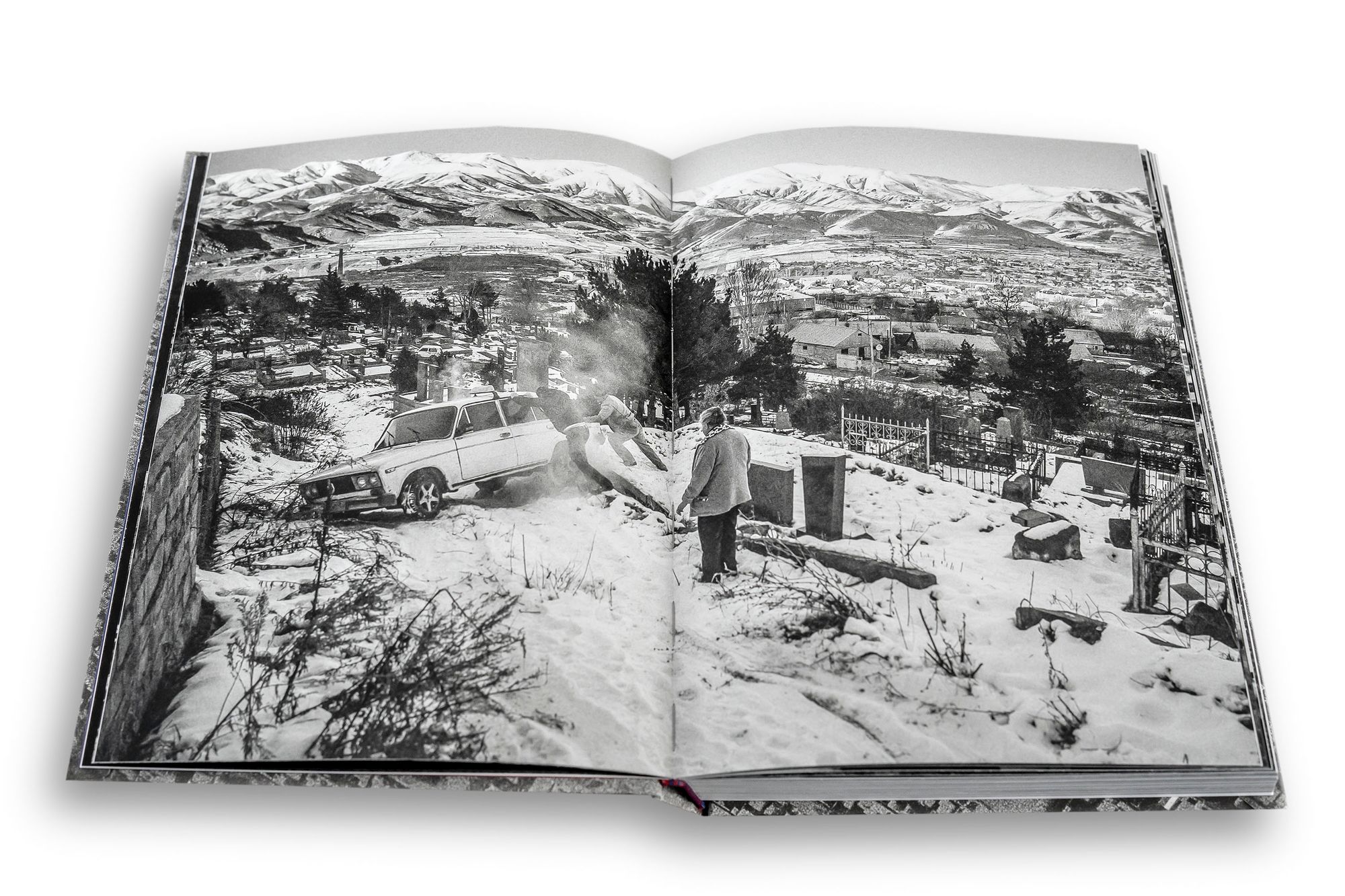

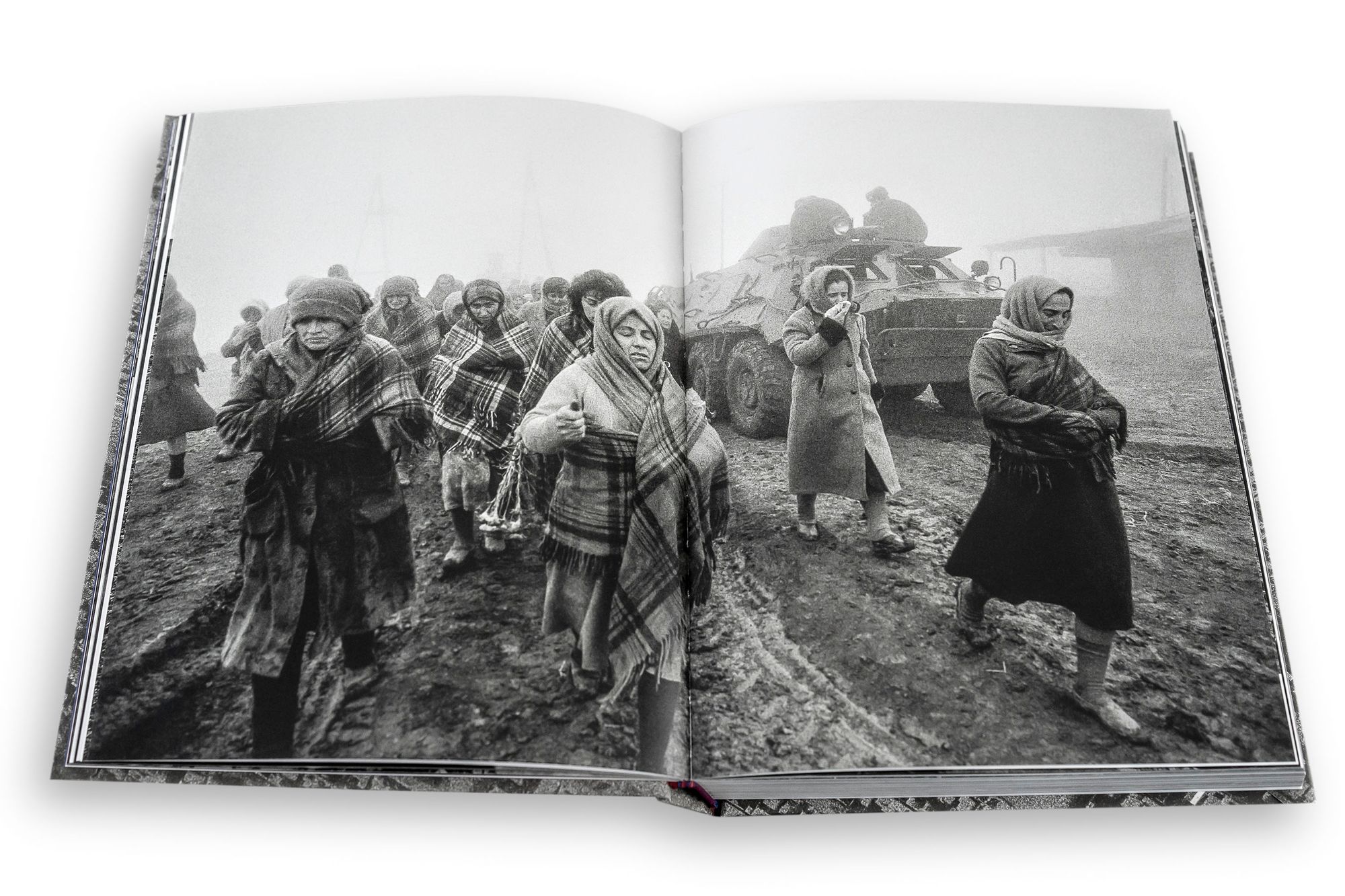

Mariusz Forecki is a documentary photographer and author of several books. In his photobook titled Kurz /Пыль/Dust, he gathered photographs from his numerous travels around the former Union of Soviet Socialist Republics—in the final stage of its existence and during the formation of a new socio-political order. He watched the former member states of the USSR regain their independence, saw the birth of new states, the struggle for identity, the return of displaced nations, and emigration in search of a better life. We asked Mariusz about his travels, experiences, and the making of the photobook Dust.

The photobook Dust depicts mainly your travels around the former Union of Soviet Socialist Republics from around the 1990s. Which countries did you visit back then?

I started traveling when I went to photograph the earthquake in Armenia in 1988. It was during the final stage of the USSR, and getting a visa was no longer as complicated as before. At that time my approach to photography also changed completely, and I became more and more interested in people caught up in different socio-political systems. Later, more trips followed: back to Armenia, Ukraine, Afghanistan, Chechnya, Lithuania, Russia, Dagestan, and the Autonomous Jewish District in Russia. I also visited Hungary to photograph Imre Nagy’s funeral.

Did you make these reportages on an assignment or by yourself?

I worked in the editorial office of the weekly news magazine Wprost, which had a very small circulation, and later, from 1991 in the editorial office of the weekly Poznaniak. They were enthusiastic about photography, but there was no money for such trips. I had already had a passport since 1988. Fortunately, the cost of going to former Eastern Bloc countries was small in contrast to that of visiting “capitalist” ones, where my monthly salary only covered a few subway rides. Preparations for the trip included finding the stories I wanted to photograph myself, financing the trips myself (sometimes with another colleague), and the editors turning a blind eye to my absence for several weeks. Upon my return, the photos were published in the newspaper. The money I received for the publication partially covered the travel costs. Since 1998 I am no longer affiliated with any editorial board and I make my own travel decisions.

What was your working method when reporting in dangerous situations, for example among the Chechens?

I had no fixed working method. I also had no patterns on how to prepare for such trips, and I didn’t know any photographers working this way. There was no one to ask. Now it is different, but in the 1990s there was no internet yet, and telephone communication was very difficult (for example, to make a phone call to Paris you had to wait several hours, and to the USSR it was not possible at all). In those days, such a trip was like disappearing for several weeks into an inaccessible and unknown space.

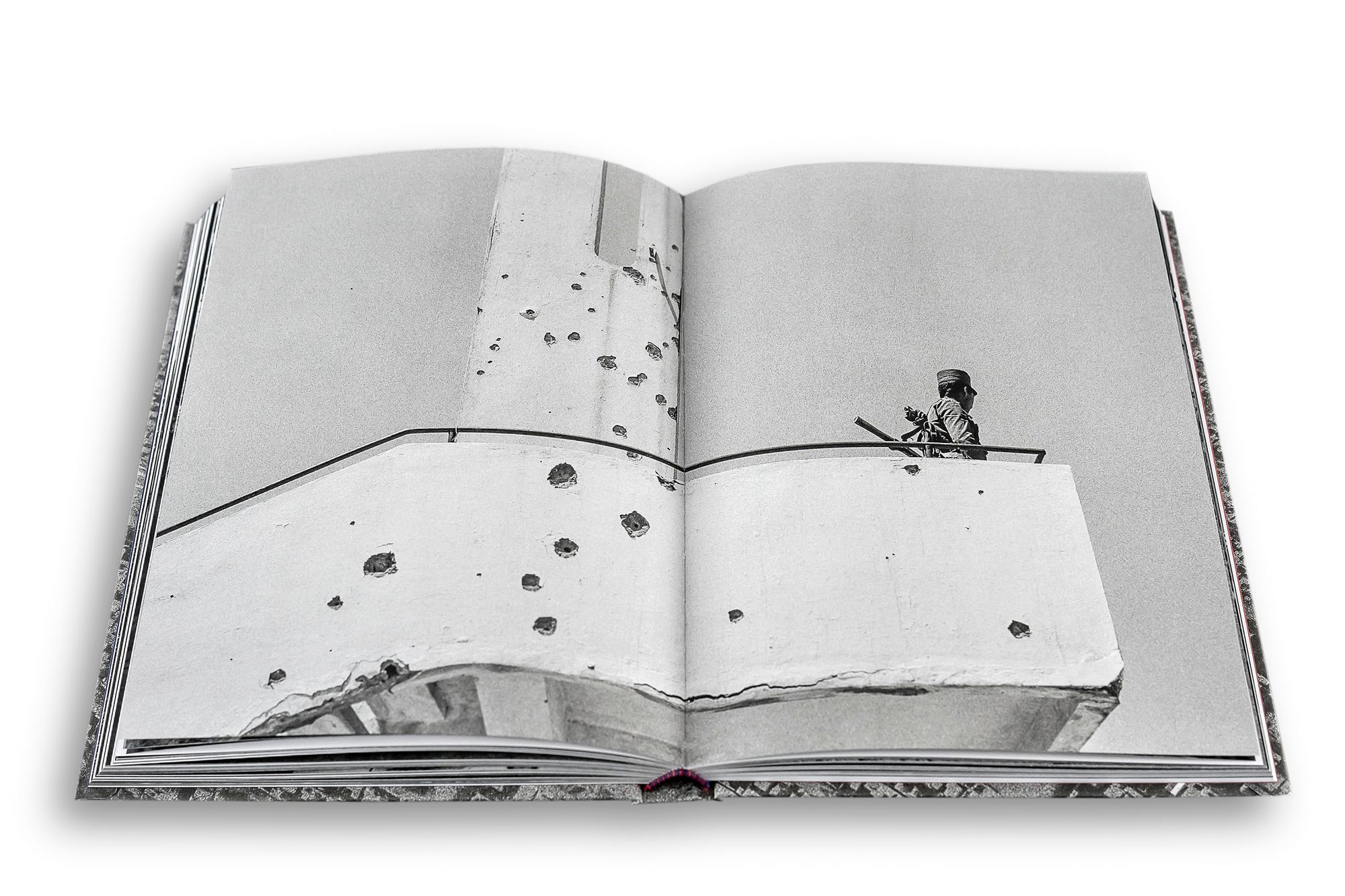

Anyway, basically, I bought a train or plane ticket, and when I got there, I would start looking. I would often let myself get carried away by people I met, for example, militiamen or soldiers. Or I went to local government officials or the school principal. My appearance and requests were so exotic that I often got what I wanted without paying. There were no problems with accommodation either. I always took a sleeping bag with me and could sleep anywhere: on the floor of a local museum, in a random apartment, in a school, at an airport checkpoint, or on a bench. It was the same with the trip to Chechnya. I got completely carried away by chance, and a few hours after leaving Poznań I found myself in the suburbs of Grozny, in a unit commanded by Shamil Basayev (considered one of the greatest terrorists, responsible for the attack on the Moscow metro or the hospital in Beslan). The then-president of Chechnya, Dzhokhar Dudayev, also visited the unit. Mothers of young Russian soldiers also came to pick up their sons from Chechen captivity. And later at night, with supplies, ammunition, and the mother of a Russian soldier, I accompanied Chechen soldiers to the center of Grozny, where in the bunker of the Presidential Palace (of which today there’s no trace) Chechens defended themselves from Russian military attacks.

You witnessed the birth of the Republic of Lithuania in 1990 (or at least an important step towards it). How do you remember this event?

Photographing in the Lithuanian Parliament was a special and personally important event for me. My family is of Lithuanian descent, from the vicinity of the small town of Kybartai on the border of the Russian Kaliningrad region. In 1944, they fled to Poland from persecution by the USSR authorities and stayed there. And then, in 1990, I went to Lithuania for the first time. I felt great anxiety and uncertainty and had sleepless nights in the Lithuanian parliament wondering what the Russians would do.

You also took many photos of Russian Jews emigrating to Israel. How did you find this community?

At that time, there was information in the press and on television about Russians emigrating en masse to Israel. I considered this an important story and used the above-mentioned method. I started looking for people on the spot, but after a few days, I found no one. Then I approached a man at the bus stop who was wearing the kind of Russian watch I always wanted but couldn’t buy in Poland. It was called “Komandirskie.” It turned out that the man was going to leave the USSR for good in a few days, emigrating with his family to Israel. After that, it was very easy.

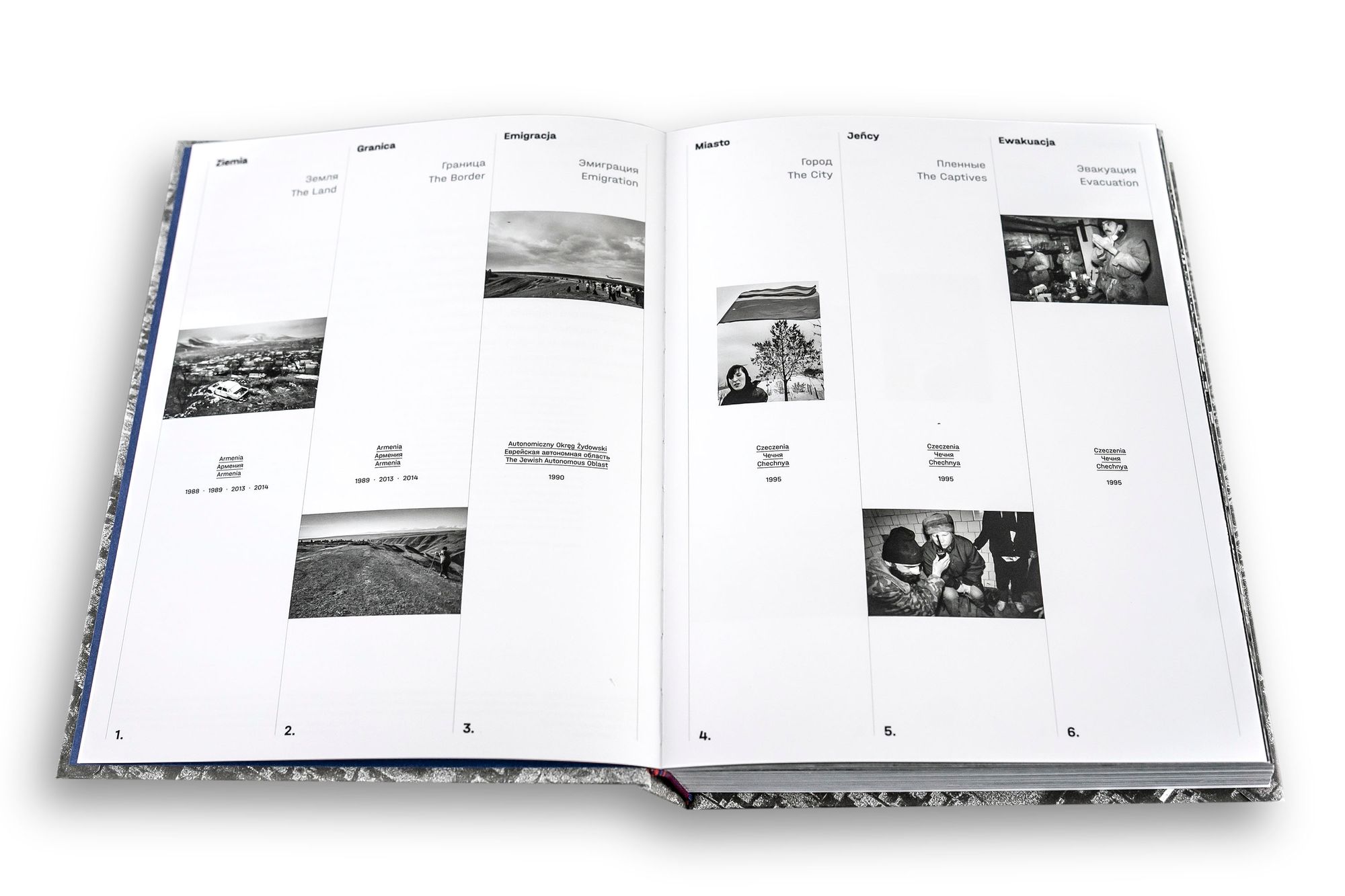

The book contains images of historical events (wars, revolutions, disasters) as well as images of everyday life (portraits, festivals, concerts). How did you select the photos?

I didn’t see many of them until 2021. For a long time, I had no motivation to scan them or any idea what to do with them. At the end of 2021, after digitization, all my previous work began to come together, and I started working on the book. I went through the photos and arranged them so that each chapter is a story in the book. I remembered the emotions that the people and places I encountered at that time evoked in me. It was these emotions that formed the axis of the entire book, creating a long story.

Your work spans several decades: you also took photos in the 2000s and 2010s. How do you see the last 30-35 years and the future of our region (Central and Eastern Europe)?

This is a question for a political scientist or sociologist to answer but as far as I’m concerned, I find it hard to understand that we haven’t learned anything from the last two world wars. I’m also surprised by how easy it is now to manipulate people. Propaganda through refined tools of control and brainwashing has become very effective. We often succumb to it without noticing. We consider our peace and well-being the most important. I realize with dismay that I myself am beginning to succumb to such propaganda. In addition, there is also rapidly developing artificial intelligence that is becoming increasingly difficult to escape from.

Why did you choose the title Dust? What does it mean to you?

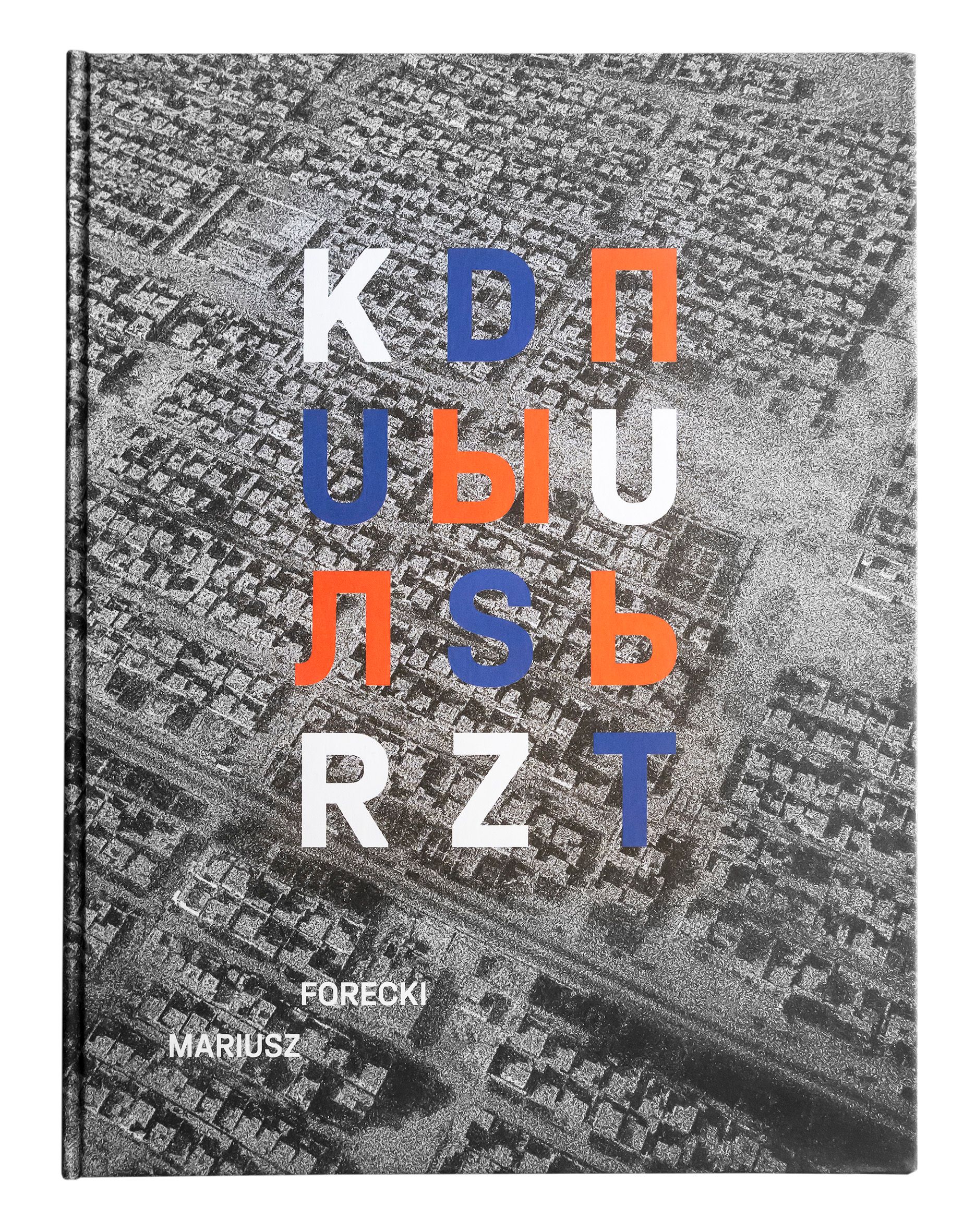

The title of the book is “Dust” written in three languages, with letters in three colors: white, blue, and red. They form a puzzling mosaic that takes time to decipher. This is a reference to the situation when a building collapses and dust is created. Only when it dissipates, when it settles down, when our sight penetrates through this dust, can we see what is left after the collapse, what emerged from it. The book was published at the end of 2022 when it was already clear that war had emerged from the dust after the collapse of the USSR.

Why did you decide to publish this photo book now, in 2022?

Between 2013 and 2018 I photographed in Russia, and in 2018 in Ukraine. The tension was already tangible. In mid-2021, I realized that I had recorded some important events, which are the stages of the collapse of the USSR and the evolution of what was left afterwards. Most of my books are about human beings caught up in socio-political processes (Man in Dark Glasses, 2016, Mechanism, 2019, Bluebox, 2020). I finished working on the book in December 2021, and at the end of February 2022, the war in Ukraine began. Then the last chapter of the book was written, telling the story of the first wave of refugees. Colleagues from the Pix.House Foundation for Documentary Photography, which published the book, helped raise the money for its publication, and the ZAiKS Association and the local government of the city of Poznań also contributed.

Mariusz Forecki: Kurz /Пыль/Dust. Pix.House, 2022

Mariusz Forecki | Web

In our Printed Pasts series, we focus on the past and the recent past of the Central Eastern European region through recently published books of different genres.

Inclusiveness in the ear—Introducing hEarrings | Dress-coding

The liminal cosmos of Jared Pike | #DIVE