How to make a small kitchen viable? What existing and newly designed objects are needed to carry out kitchen operations with as little annoyance as possible, or even more: making cooking, eating or even just preparing a cup of tea a pleasure? These were, among others, some of the questions being addressed by the first system-design-based project in Hungary, the Kitchen Program for Prefabricated Houses. Object fetish EXTRA, in duo!

Authors: Kitti Mayer & Piroska Novák

We dedicate this article to Mihály Pohárnok.

The Kitchen Program for Prefabricated Houses has been mentioned several times in our previous Object Fetish articles (we touched the subject in connection with the Termover heatproof dish set designed by Katalin Somkúti[1], and we also referred to it in the section on the Saturnus set (see here and here), so we thought the time had come to present this inevitable chapter of Hungarian design history in this episode. Because, in many ways, this experiment requires a separate discussion. Why?

On the one hand, because it was the first comprehensive project based on system-based design in Hungary, and therefore a prime example of the kind of design approach that we now take for granted in design practice. Namely that, the designer starts designing an object, a system or a service—offering a solution to the problems and deficiencies that arise—after having assessed the user’s needs and after thorough research. On the other hand, because this story is a telling account of the fact that, however, driven by the desire to improve, the designer is not enough to bring about spectacular change in industry and commerce (because, as always, a well-designed object can only really achieve its purpose if its potential is recognized by industrial decision-makers and they are willing to make it available to users who see a need).

For most of us today, the kitchen doesn’t have to mean a handkerchief-sized, dark, chaotic and cluttered room. For us, the kitchen is the American-style model, with a bright, spacious space, a logical arrangement of appliances and objects, space for all utensils, and a pleasure not only to cook but also to eat in. But this was not always the case.

“This article should be written in the kitchen,” Judit Fekete begins her review of the Kitchen Program for Prefabricated Houses in the pages of Művészet, and then continues, “partly because it is about the kitchen, its room for maneuver and furnishings, and partly because it is the room furthest from the bedroom, so it is the least likely to be the place from where the typewriter’s clacking would come in at night. But the kitchen, like most of the day, is empty.”[2] From these few sentences, it is clear that the kitchen at this time cannot be called the “soul of the home” (as we usually think of it) at all and for a reason.

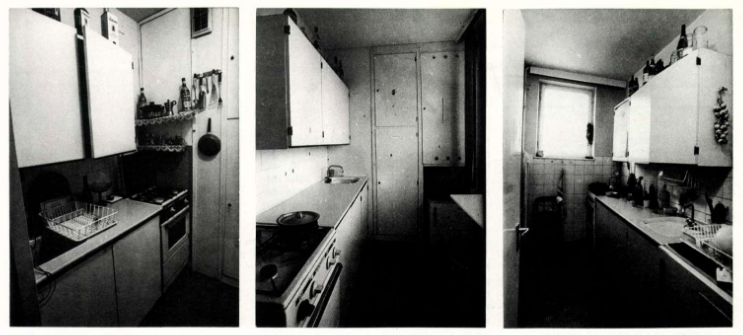

The kitchens of the prefabricated houses could hardly have had the “superpowers” we now take for granted. The kitchens of factory-built apartments, “invented” to solve pressing housing problems resulting from the world wars and social reorganization, usually had a floor area of 5-8 square meters, sometimes with a pantry or an attached dining area, and a few inalienable accessories such as built-in standard kitchen units, a sink and a stove.

How did the kitchens of the prefabricated houses look like? As confirmed by photo documentation taken during the program, and as we can read in József Vadas’ book: “The gloves, dishcloths and cleaning brushes on the gas pipe not only drew attention to the need to make every detail of this small room economical but also indicated that the tools are currently being replaced by forced solutions. The lack of space explains the hanger on the side of the cupboard, the tin shelf in the corner on which the coffee machine stands. (…) The windowsill is a veritable arsenal: ashtrays, tobacco, medicine, but even the soda siphon and the salt shaker found home there. (…) And the experience of messiness is only heightened when we look in the drawers or cupboards.’[3] And the ‘creativity’ of the residents seemed to be unlimited: “This is how a washcloth and a match were placed in the soap dish, a towel cloth on the tension rod connecting the table legs, a shopping bag hung on the radiator valve, a spark lighter on a nail in the wall (…).”[4]

This relatively isolated, rather small space, but the scene of many activities, was the subject of a design experiment by three young designers, Sándor Borz Kováts, György Soltész and Mihály Pohárnok, in December 1972. Perhaps at the outset, they had no idea of the challenges that this tiny space would present. But they knew one thing for sure: a complex approach and systematic research were needed to make a difference and make the project a success.

The “why” and the “how”

“…the prefabricated houses are becoming increasingly important in the domestic urban construction of the near future, (…) in these dwellings, which are cramped despite their comfort, it is particularly important to coordinate kitchen functions concentrated in a few square meters. The kitchen was therefore not only a suitable experimental subject but also a pressing task,” writes József Vadas in his book Nem mindennapi tárgyaink.[5] The Pohárnoks were primarily driven by the desire to raise the standards of production and design, which should not be confused with setting their minds to design purely aesthetic objects. Far from it. They wanted to turn the kitchen into a well-functioning system where space, object and man (as cogs in a wheel) work together in a well-oiled system. They could not change certain features of the system (layout, positioning and size of the built-in furniture), however much they wanted to. The aim was therefore to fill the kitchen with objects that would make life easier for the residents. But who the residents are, and what exactly is their job, was something they had to find out for themselves.

The first step of the program was to collect the available research (housing sociology research, dietary habits surveys, company market research reports, industrial supply, etc.) and to consult scientific experts who reported to the team on the different eating habits, hygiene, ergonomics and psychological requirements. But the empirical approach was not left out either: in May 1973, forty apartments in Újpalota were visited, and in 1974 a further thirty apartments in the Árpád-Híd and Kelenföld residential areas (the designers themselves—György Soltész, Anikó Preisich, Tibor Szentpéteri, Péter Csíkszentmihályi, István Ferencz, Ildikó Vincze, Magda Gál, Mihály Pohárnok—also took part in the survey in Óbuda).

The designers also had to determine what functions the kitchen should be able to perform (How often is cooked food prepared? At what times and where exactly do family members eat? How often does the dishwashing or ironing take place?) and what work processes are associated with these functions. They also needed to see which meals are prepared more frequently or what basic ingredients need to be stored. The twenty-seven-page questionnaire, prepared with the support of the Népművelési Intézet, had one hundred and six questions, such as “How many times do you buy food per week?”, “How many jars of preserves do you keep at home?”, “Do you use a tablecloth?”, “Do you use the same cutlery on weekdays and holidays?”, “Do your children have their own separate glasses?”. [6]

As the research progressed, the picture became clearer: what are the tools we really need in the kitchen? The designers of the Kitchen Program for Prefabricated Houses were not driven to populate the kitchen cabinets and drawers only with their own objects: they themselves analyzed the existing range of goods (they studied the product tests of the Nagyító magazine, and asked about the non-qualified products directly from KERMI), and only started to design a new object family if they could not find a commercially available product that could perform the desired function. In June 1973, to conclude the first part of the work, a study entitled Tervezési követelmények (Design requirements—free translation) was published, in which designers “pay equal attention to function, cleanability, harmonious relationship with the environment (…), surface properties and aesthetic appearance.”[7]

From exhibition to exhibition

An exhibition of the results of the first year of the Kitchen Program for Prefabricated Houses opened in November 1973 at the Fészek Artists’ Club, the same place where the whole initiative started. The direct antecedent of the kitchen program was the exhibition entitled Hungarian design (10 experiments) organized in October 1972, by Sándor Borz Kováts, Mihály Pohárnok and György Soltész (we have both written about this exhibition and its current, rethought version here and here). The exhibition of the eight designers aroused great interest and response, taking advantage of which, the start-up of the Kitchen Program for Prefabricated Houses was brought to life, which not only sought to ensure the smooth operation of prefabricated kitchens but also demonstrated the complexity of design and designer in the profession, industry and in front of consumers.

The results of the research and surveys and the steps of the design method were presented at the exhibition a year later. In today’s terms, visitors could see infographics and data visualization diagrams and tableaus—this exhibition was more for the profession, less for the general public.

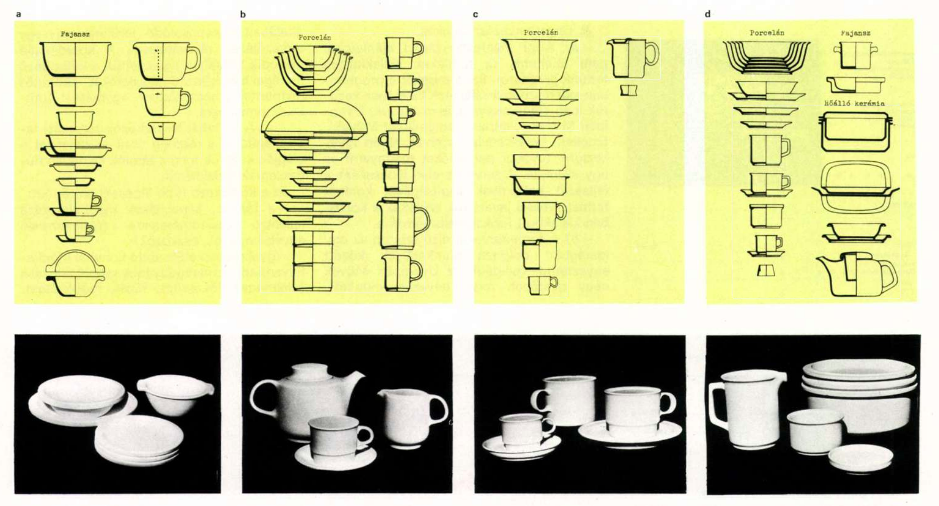

The design started in the spring of 1974: after evaluating the data, the needs assessment and the development of functional schemes were based on the principles of system-based design or, as the experimental documentation called “coordinated” design, where it is not the finished product that points in the direction of the process, but a given kitchen process designates a range of products designed to be optimized for the function and to provide multi-purpose use. With a detailed description, the Pohárnoks announced a competition for designers in the fine ceramics, enamel and glass industries, with the support of the directors of trusts that connected industries and factories—Fine Ceramics Industry Works, Enamel Industry Works, Glass Industry Works. Further preparatory meetings were held on the design of wood, plastic and textile objects. It can be concluded from the above that the organizers of the program did not primarily work as (product) designers, but also as theorists and design managers, as the experiment also aimed to organize successful cooperation between design teams, industry and trade representatives. And the fact that the work was carried out with the involvement of other professions allows us to evaluate the Kitchen Program for Prefabricated Houses as a multi- and even interdisciplinary experiment.

“The ceramic competition will be judged on 24 June 1974 and the glass design competition on 3 July (…). The winners continue to work, the prototypes are being made, and the idea that the companies participating in the kitchen program at the Budapest International Fair of autumn 1975 exhibit the objects together is becoming a decision. The fruit is ripe.”[8]

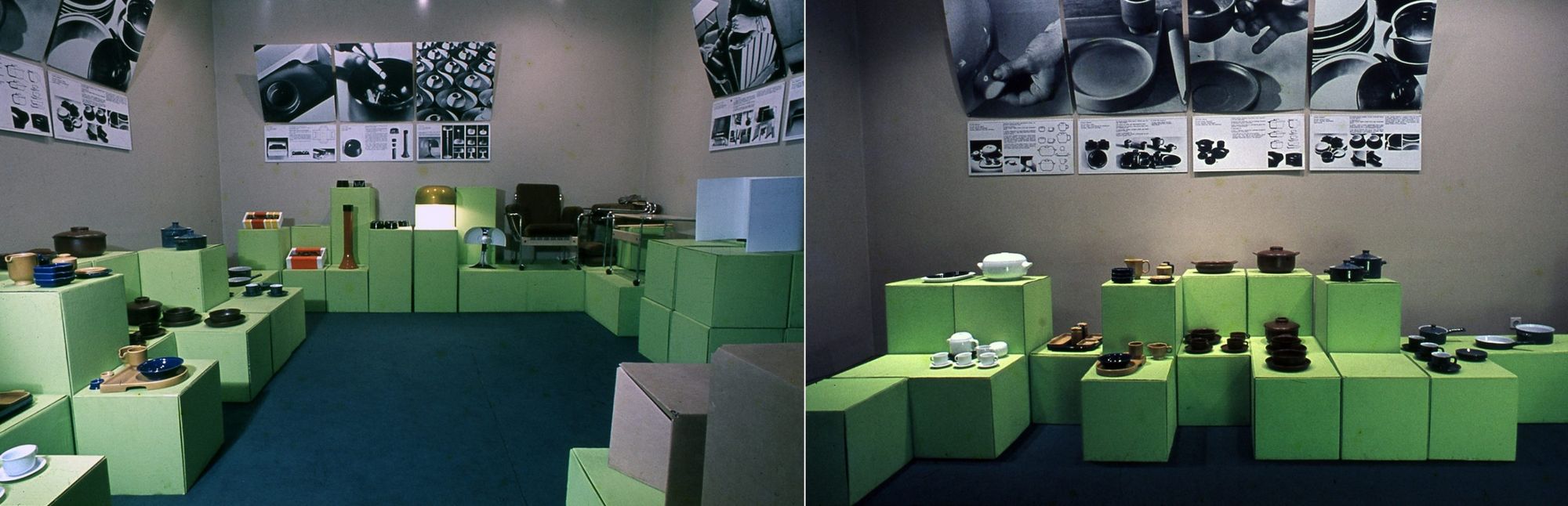

The completed and judged prototypes were presented at the Budapest International Fair (BIF) in the autumn of 1975 at a stand of two hundred square meters rented jointly by the mentioned trusts. The event summarizing the results of the Kitchen Program for Prefabricated Houses featured not only the newly designed objects, but also the products already on the market that correlated with the goals of the experiment, so the audience could see nearly four hundred objects. The green installation of the exhibition was designed by Emil Gaul and László Zsótér—similarly to the previous exhibitions of the program.

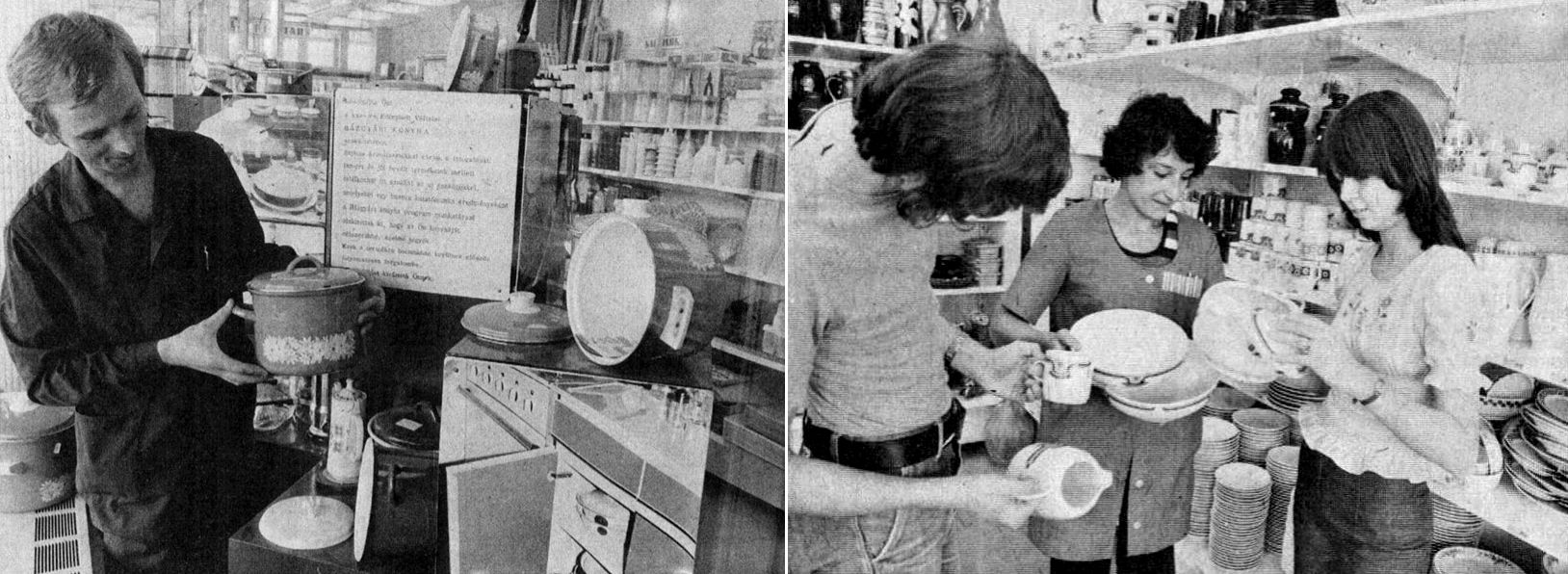

After a highly successful summary and introduction, the prefabricated kitchen shop of the Fővárosi Vas- és Edénybolt Vállalat (Budapest Iron And Utensil Company—free translation) was opened in Kelenföld in May 1976, where objects made and approved during the program were distributed.[9] But unfortunately, after a few years, the store changed its product range, as few of the objects planned during the kitchen program eventually became mass-produced, commercially available products.

Objects, products, prototypes

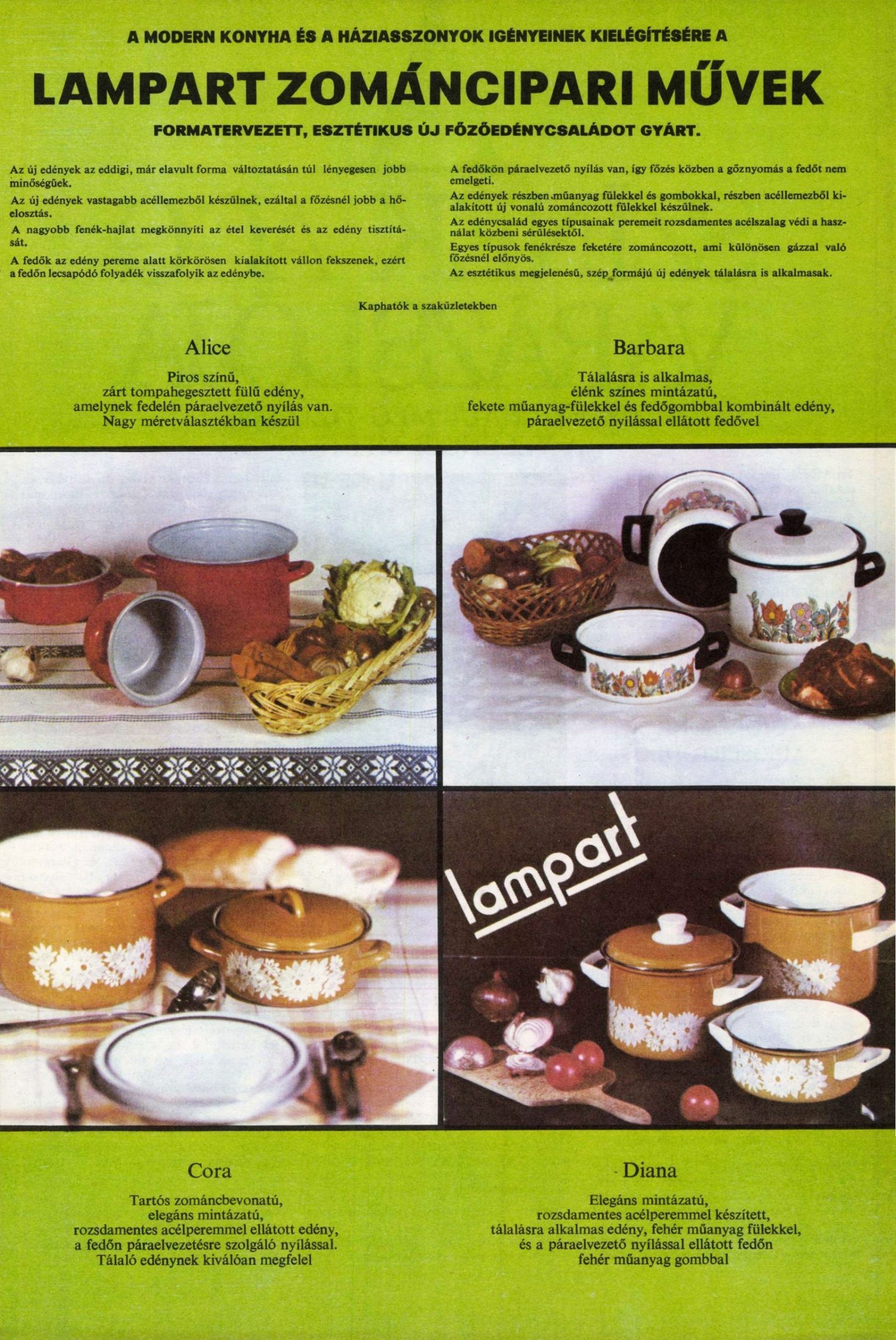

During the experiment of the Kitchen Program for Prefabricated Houses, there were people who saw the real and complex market-commercial opportunity that the program offered. Typically, representatives of these people, trusts and factories, went beyond the level of exhibition prototypes and came up with products. Lampart Enamel Industry Works already made a positive statement about the experiment at the BIF in 1974, and after 1975, so after the end of the program, they used the designers of the Kitchen Program for Prefabricated Houses as a consultant. Led by Csaba Ásztai and György Soltész, pans, pots, kettles and kitchen utensils were born, which the large company itself was happy to report in its paid advertisements.[10]

The kitchen utensils made of enameled sheet steel had several innovations: the pots and pans were designed to fit in the kitchen cabinet stacked on top of each other, their lids were designed with a gap for the removal of water vapor, and their solid metal or plastic handles could be easily cleaned. Their single-color or flower-patterned versions were based on the survey data that most housewives serve by placing the cookware directly on the dining table, so they should also have an aesthetic appearance. Perhaps this is why the products have been given female names in trade: Alice, Barbara, Cora, Diana.

The Metalwork Collection of the Museum of Applied Arts preserves solid blue, ocher and white enamel objects, which were donated to the institution by the Design Center led by Mihály Pohárnok, together with other memories of the kitchen program. (For the online thematic selection of the prototypes and products created as a result of the Kitchen Program for Prefabricated Houses in the collections of the Museum of Applied Arts, see here.)

On behalf of Glass Industry Works, several factories participated in the Kitchen Program for Prefabricated Houses. The apple grater and lemon press made of natron glass were made at the Salgótarján Glass Factory, designed by Júlia Kovács. However, the coolers designed by György Rénes, the spice holders based on the glass-metal material association, listed together with György Radnóti, and the sets of glasses with press technology were not put into production. Compote and cake services were made under the leadership of Tibor Házi at Ajka, but they were also stuck in prototype production. At the Kracag Glass Factory, on the other hand, popular products were born, which were mentioned by both the profession and the customers as “the Hungarian jénai”. Katalin Suháné Somkúti designed heat-resistant glass in the factory, based on the patent of Zoltán Veress, in which dishes could be both baked and served.

In the three factories of the Fine Ceramics Works—the Alföld Porcelain Factory, the Városlőd Majolica Factory and the Granite Polishing Stone and Earthenware Factory—they joined the system-based design experiment of the Kitchen Program for Prefabricated Houses, unfortunately, none of them developed products, only indirectly. At the Alföld Porcelain Factory, Éva Ambrus designed a complete table set, which was even accompanied by a transfer print, the work of Zsuzsa Péreli and László Zsótér. However, this is perhaps where the lack of coordination in the experiment became apparent, as the size of the decal failed to match the decorative surfaces of the plates. The lessons of the Kitchen Program for Prefabricated Houses were drawn in the design theory and practice of Éva Ambrus’ major work of her factory design era, the UNISET-212 catering set (see our article on the service here). Károly Szekeres designed a set from the red fired, heatproof clay used in the Városlőd Majolica Factory, of which prototypes of a teapot and a pot with a lid are in the museum’s Ceramics and Glass Collection, although according to the memoirs of the designer’s widow, Emese Vásárhelyi, also a ceramist, these were not made in the factory either, but in Szekeres’ workshop as a self-produced piece.

At the Granite Factory, Gabriella Semsey designed a service from the factory’s special yellowish-burning faience (which was incorrectly often called majolica in contemporary reports). The object family was later further developed with Maria Minya, and their joint work won them the Hungarian Design Award in 1980. The pieces in their collection are based on simple shapes in the spirit of Scandinavian design, decorated with colorful glazes and discreet hand-painting.

Legacy of the Kitchen Program for Prefabricated Houses

The enormous undertaking of the Kitchen Program for Prefabricated Houses, despite the huge amount of work that has been put in, has achieved only a small amount of direct results, but this was not down to the organizers. They offered a complex and progressive solution to a system that was not yet ready for it. From another perspective, the experiment of the Kitchen Program for Prefabricated Houses has produced a number of indirect results. Their work led to a restructuring of the governance and organization of industrial art and design; the Applied Arts Council was abolished. It was replaced, among other things, by the Industrial Design Information Center, which functioned as a Design Center, headed by Mihály Pohárnok. The journal, Ipari Művészet (Industrial Arts), until then only available to a limited audience, was relaunched as Ipari Forma (Industrial Design) with a new editorial team. As a long-term consequence of the program, system-based design and fieldwork, which provides practical experience, have been incorporated into design theory as basic methods in design education. A further indirect result of the Kitchen Program for Prefabricated Houses was the creation of a series of objects designed along the lines of the new design approach, thus shaping and leaving their mark on the domestic object culture of the period.

The Kitchen Program for Prefabricated Houses and its forerunner, the Magyar design (10 kísérlet) (Hungarian Design, 10 experiments) exhibition, were developed in academic detail at the Moholy-Nagy University of Art and Design in 2015 and this year.[11] The choice of themes also underlines the fact that these two events are key and defining moments in Hungarian design history, the legacy of which is worth, and even must be, shared with as many generations as possible. In 2022, we will commemorate the 50th anniversary of the launch of the Kitchen Program for Prefabricated Houses.[12]

In our Object Fetish series, we told you about emblematic pieces of domestic object culture. We explored objects and their designers: we asked questions, we investigated, we discovered. The pieces created in the collaboration of Kitti Mayer and Piroska Novák, design theorists, were published between 2019 and 2021.

Collaborating partner for the series:

Notes:

[1] The designer’s name is spelled Somkuti in some sources.

[2] Fekete, Judit: Egy rendszertervezés rendszertelenségei. In Művészet. 1977 (August), Vol. 18, No. 8, 12-13. [The source of the quotations is on page 12.]

[3] Vadas, József. A házgyárikonyha-program. In Nem mindennapi tárgyaink. Budapest: Szépirodalmi Könyvkiadó, 1985, pp. 341-360 [Source of quotation on pages 352-353].

[4] Vadas, József: op. cit., 353.

[5] Vadas, József: op. cit., pp. 347-348.

[6] Vadas, József: op. cit., 349.

[7] Vadas, József: op. cit., 351.

[8] Vadas, József: op. cit., 353.

[9] Cs. Benkő, Judit: Tudod-e, mi az a Házgyári konyhaprogram? Családoknak – „tárgycsaládok”. In Magyar Ifjúság. (14 November 1975), Vol. 19, No. 46, 28-29.

[10] (Ed. article). A Lampart Zománcipari Művek a BNV-n. A LAMPART a családok szolgálatában. In Világgazdaság. (11 October 1975) Vol. 7 No. 1692, 7.

[11] Kitchen Program for Prefabricated Houses 1972-1975—Exhibition and symposium organised by the Moholy-Nagy University of Art and Design (Ponton Gallery, 1015 Budapest, Batthyány Street 65., 17-27 March 2015.)

Magyar design – 10+1 kísérlet (Hungarian design, 10+1 experiments—free translation)—Exhibition organised by the Moholy-Nagy University of Art and Design (Fészek Gallery, 1073 Budapest, Kertész Street 36., 2 November 2021—2 January 2022)

[12] In addition to the writings already cited in the text, the following are the most important contemporary sources on the Kitchen Program for Prefabricated Houses:

Péter Búza: Tenger a teáskannában. In Magyar Ifjúság. 1974 (4 October), Vol. 18, No. 40, 19.

I. CS. (Imre Csatár). Design. Kísérérlet a konyhával. In Magyar Nemzet. 1974 (19 April), Vol. 30, No. 90, 5.

csatár (Imre Csatár): A konyhaprogram. Már nem kísérlet. In Magyar Nemzet. 1974 (12 September), Vol. 30, No. 213, 6.

Csatár, Imre. Útközben. Hamis lobogók. In Magyar Nemzet. 1977 (4 September), Vol. 33, No. 208, 10.

Csatár, Imre. A magyar „design” útja. In A Magyar Hírek Kincses Kalendáriuma 1977. Iván Boldizsár (ed.) Budapest: Magyarok Világszövetsége, 1977, 105-109

Cs. Benkő, Judit. Tudod-e, mi az a Házgyári konyhaprogram? Családoknak – „tárgycsaládok”. In Magyar Ifjúság. 1975 (14 November) Vol. 19, No. 46, 28-29.

Ernyey, Gyula. Az ipari művészettől a rendszertervezésig. III. Szocialista tervezés. In Művészet. 1977. (May), Vol. 18, No. 5, 36-39.

Ernyey, Gyula: Kitchens for prefab housing units. In Made in Hungary. The best of 150 years in industrial design. Budapest: Rubik Innovation Foundation, 1993, 124.

Pohárnok, Mihály: A Házgyári konyhaprogram. In Ipari Művészet. 1974/1, 3-11.

Pohárnok, Mihály. Miért a konyha? In Magyar Nemzet. 1974. (21 May), Vol. 30, No. 116, 8.

Pohárnok, Mihály: Egy tervezési kísérlet dokumentumaiból. A Házgyári konyhaprogram négy éve. In Művészet. 1977. (August), Vol. 18 No. 8, 2-11.

Soltész, György. Házgyári konyha-program. Dokumentumok egy tervezési kísérletről. In Mozgó Világ. 1977. (April), Vol. 3, No. 2, 60-73.

SZ., T.: Eredményes vita nyomán. Minden elfér a kis konyhában. Praktikusabb bútorokat gyártanak. In Esti Hírlap. 1974. (December) Vol. 19, No. 293 [No page numbers.]

Tamás, Mihály. Mikor lesz rend a konyhában? In Népszabadság. 1975 (29 December), Vol. 33 No. 303, No. 8.

Vadas, József: Tárgyaktól a tárgyilagosságig. In Élet és Irodalom. 1973. (1 December), Vol. 17, No. 18, 12.

Vadas, József: Serleg a konyhaasztalon. In Élet és Irodalom. 1974. (30 November), Vol. 18, No. 48, 4.

Vadas, József: Konyha a kirakatban. In Élet és Irodalom. 1975. (8 November), Vol. 19, No. 45, 12

Vadas, József: Rend van-e a konyhában? Egy tervezési kísérlet. In Valóság. 1980. (1 June), Vol. 23, No. 6, 86-97.

Vámossy, Ferenc: Új szemlélet az építészet és a tárgyalkotás területén. In Építés–Építészettudomány. Publications of the Department of Technical Sciences of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. Máté Major (ed.), Budapest. Akadémiai Kiadó, 1975, Vol. VII, No. 1-2, 257-260.

Like a local 2021—Fehérvári Street Market Hall, Fågel by Artizán, Magvető Café

TOP 10 contemporary buildings from within and beyond the region