No, this is not an essay on astronomy, and not even a review on W. G. Sebald’s novel of the same title[1]. Nevertheless, the sixth part of the Object Fetish series is, indeed, related to the solar system’s sixth planet. In this year’s first episode, we present you the Saturnus set by porcelain designer László Horváth.

Written by Piroska Novák

In Hungarian object culture, and within that, amongst the porcelain dinner sets, there is a legendary service that does not only stand out with its elegant form but also with its story full of exciting turns. What makes the Saturnus service legendary? Let’s start at the beginning!

The Saturnus set was made for the Varia dishware design competition announced jointly by the Ministry of Culture, the Applied Arts Council and Finomkerámiai Művek (Fine Ceramics Works, FIM) in 1971, the results of which were announced in the summer of 1972. The first prize was awarded to Éva Ambrus’s “Bella” set in the category of complete tableware, which we have already introduced to our readers in the third part of our Object Fetish series. The award committee also appreciated László Horváth’s proposal with a special award of HUF 50,000, which was quite a decent sum back then. The Saturnus set didn’t come near to the call’s criteria, but all experts praised it, especially for its innovative design clearly manifesting a familiarity with Scandinavian aesthetic. The person who praised the set most enthusiastically and who also cleared up the legends related to its story—by addressing the topic in several of his writings while also exploring links to cultural politics and economy—was art historian József Vadas.[2]

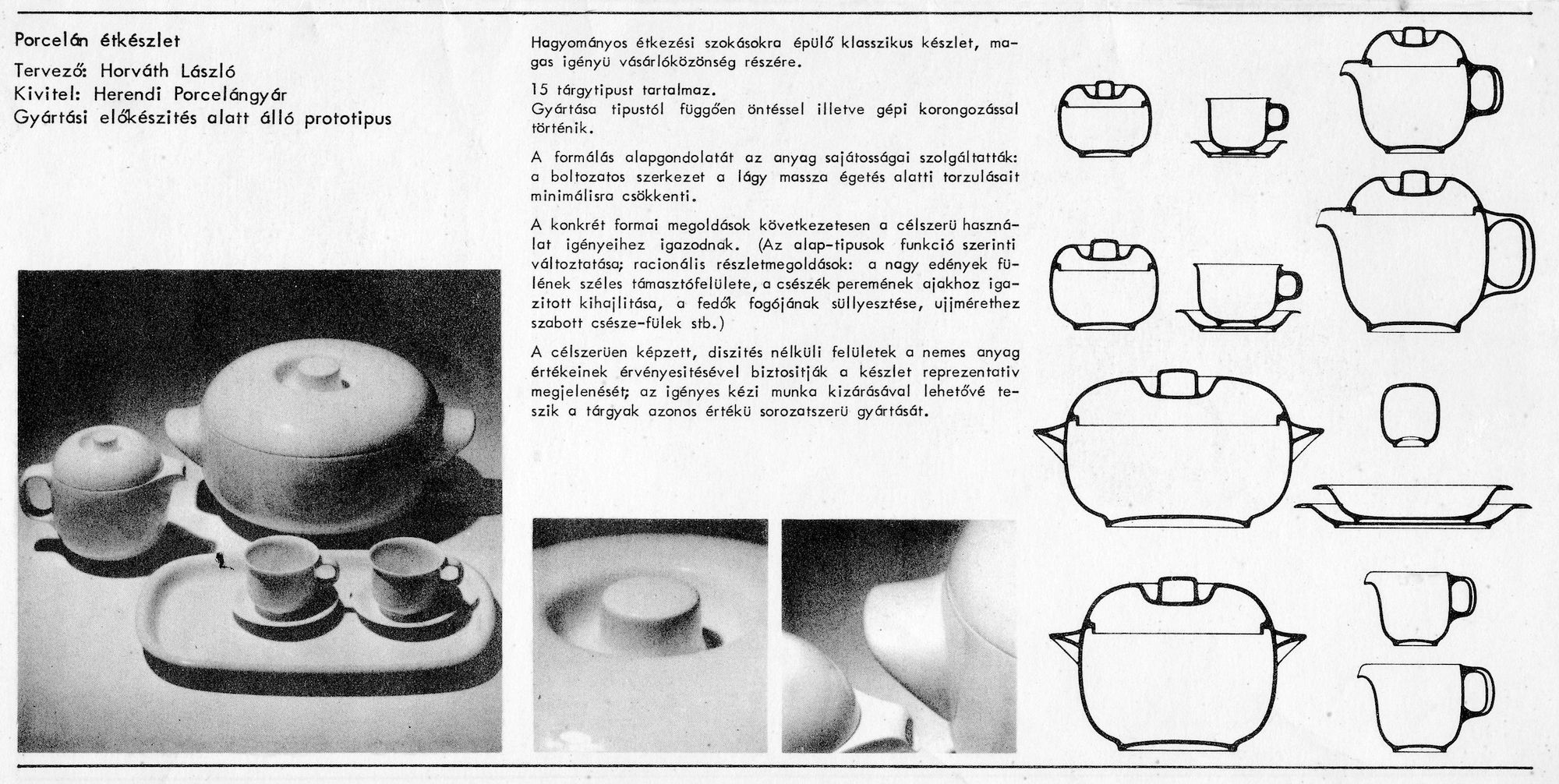

Besides having to meet the needs of the consumers of the time—fulfilling various kitchen and serving functions, saving space, modern design—, the proposals submitted to the Varia design competition fundamentally had to fulfil two criteria. On the one hand, they had to be suitable for manufacturing with industrial technology on the semi-automatic production line of the Alföld Porcelain Factory in Hódmezővásárhely brought to Hungary from the GDR. On the other hand, it was important that the pieces of the set could be purchased separately, at the consumer’s own discretion, instead of purchasing a complete set, thus allowing the customer to vary the pieces as they like and making sure that the pieces are replaceable and can be produced in the long-term. Glass designer Nikolett Dárday published a vitriolic review on the competition and the proposals submitted in the paper Ipari Művészet[3], even picking at the details of the awarded projects. Yet even she spoke favorably of the Saturnus set, and mentioned in her piece that if not in Hódmezővásárhely, it would definitely be placed into production in the Hollóházi Porcelain Factory. And why couldn’t they manufacture the Saturnus in Alföld Porcelain Factory? László Horváth was working as the designer of the Herend Porcelain Factory from 1965[4], the pieces of the Saturnus service were also made there out of Herend porcelain, using typical Herend (that is, hand-made) technology. This is what brought a resounding success for it on the Varia competition, as its taut, clean pieces with thin walls and built of outward bending elliptic arches correlated with hand-crafted Herend techniques: these delicate features would have been lost in the industrial serial production offered by Alföld Porcelain Factory.

The other reason lies in Herend Porcelain Factory itself, where the introduction of objects with innovative design and function was constrained by traditions. Owing to the domestic and particularly the foreign demand, the Herend repertoire remained of excellent quality, but it also got stuck in the world of anachronistic neo-baroque, neo-rococo dinner services, ornaments, hand-painted and hand gilded, mannered porcelain statuettes. On top of it all, the trust—as the designers called the Fine Ceramics Works back in the day—imposed strict regulations also in terms of production quota in addition to the product selection to reach the desired profit, which thus could not get out of the vicious circle of “tooth-aching dogs, dancers, sad shepherds and other bland figural compositions”[5]. And so the question arises naturally: why did a designer who achieved such a great professional success with the Saturnus set that was “modern” from every possible angle work in Herend, for long decades on top, from 1965 until 2001?

I asked László Horváth this question, and all he answered was that he was captured by the finesse of the excellent quality Herend raw material as well as the related high-quality artisan techniques when he had spent his college internship in the factory.[6] As a freshly graduated porcelain designer he thought he could reform or at least bring new colors into the factory, but he soon realized that Herend was quite hard to be forced out of its established and entrenched traditions. He made a lot of compromises for the values he mentioned earlier in the course of his career.

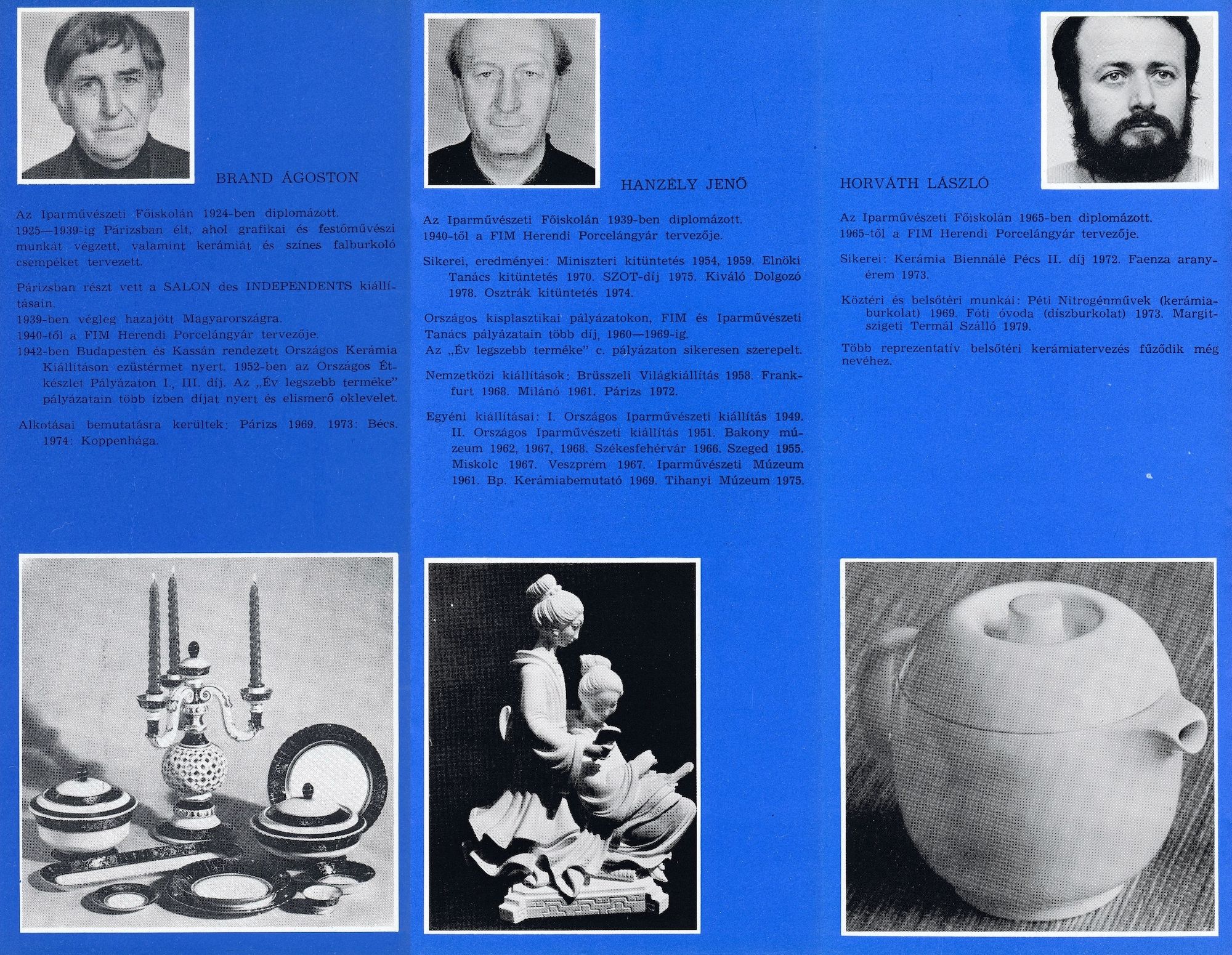

László Horváth studied at the Department of Porcelain Design of the Hungarian College of Applied Arts between 1960 and 1965. His master was Imre Schrammel. Before his admission, he worked as a semi-skilled worker in the plaster workshop of the Kőbánya Porcelain Factory for a year. It was already set in stone during his years in college that he would be hired by Herend Porcelain Factory after completing his studies, this is why it is no coincidence that he manufactured one of the tasks of his diploma project, a cold kitchen service for a fictive bar, in Herend, where no task was impossible for the excellent plaster masters. After he started working, he had to participate in “renewing” the Herend form and pattern collection—along the principles of anachronistic design—just as much as the other graduated designers, including Ágoston Brand and Jenő Hanzély.

Later on, Horváth shifted his focus on rediscovering the lithophane technique[7]. As a mandatory task, he made portraits of famous people—including Einstein, J.F. Kennedy and Michelangelo—with the technique, which were then exported mainly to the USA. He also experimented with making lamps and wall cladding by using thin lithophane sheets. One of his compositions featuring a dandelion forms part of the permanent collection of the Herend Porcelain Museum, even though this was made much more later, after FIM had been terminated and Herend Studio had been established. Herend Studio was founded in 1985, building on the works of three designers—László Horváth, Zoltán Takács and Ákos Tamás. They designed and manufactured autonomous and applied genre products in custom and limited series (see for example in the collection of the Museum of Applied Arts).

Something the designers working in FIM’s factories all have in common is that often they could only work on their projects for the centrally announced competitions after completing their full time work and their official duties. This is exactly how the Saturnus set, too, was born, which was not entered into production by Herend Porcelain Factory in spite of the special award of the Varia competition—in fact, it could not have been placed into production at all according to the rules of the planned economy in place at the time. But Saturnus’s triumph really started after the results of the Varia competition had been announced.

The awarded items of the Vaira competition were exhibited as part of the Művész az iparban (Artist in the industry) exhibition series launched by the Applied Arts Council in the Museum of Applied Arts between December 15, 1972 and January 15, 1973. In the meantime, László Horváth won another award with the Saturnus set at the 3rd National Ceramics Biennale in Pécs, where the service came in second. In 1972, a few items of the Saturnus set were also displayed at the exhibition titled Magyar design (10 kísérlet) (Hungarian Design [10 experiments]) held in Fészek Art Club, organized by Sándor Borz Kováts, Mihály Pohárnok and György Soltész. The experimental exhibition showcasing 10 works of eight designers started a meaning conversation in the paper titled Művészet about the questions of design.[8] The high-impact show and the professional debate unfolding as a result of it can both be perceived as a vortex in calling to life both the House Factory Kitchen Program and the Design Center. The Saturnus service also received a prominent place at the first exhibition held in the showroom of the latter institution in Gerlóczy utca titled Terített asztal (Set Table) in 1980—Kitti Mayer has already written about this in detail.

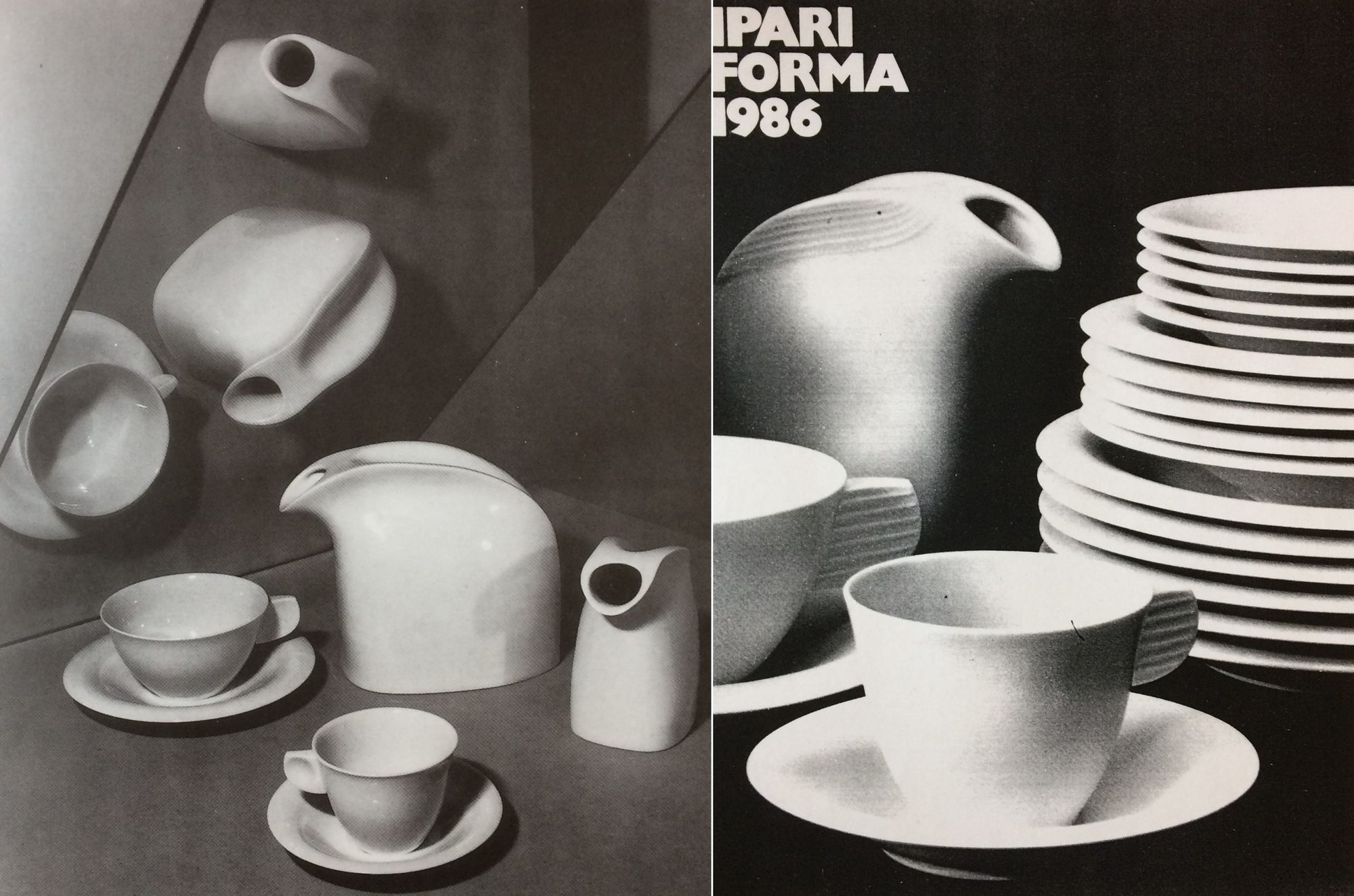

The Saturnus’s achieved its biggest international success at the celebrated Concorso Internazionale della Ceramica d’Arte (Faenza International Ceramics Competition), where László Horváth’s work came in third after Joe Colombo and Tapio Wirkkala in the category of household objects (i.e. design). László Horváth could even travel to the award ceremony together with FIM art director Dr. Győző Sikota, where the Italian Richard-Ginori and the Western-German Rosenthal porcelain concerns indeed took advantage of their “star designers” and advertising possibilities. At this time, it was uncertain whether the Saturnus set would be put into production or not. Perhaps it was the international recognition that pressured the Hungarian authorities who finally ordered the production of the Saturnus set in Hódmezővásárhely, i.e. the intended place of production of the Varia competition. However, in order to do that they had to alter the forms. László Horváth supervised this process, allowed by his colleague, Éva Ambrus, the art director of the Alföld Porcelain Factory at the time. As a result of the alteration, the wall of the products manufactured in Hódmezővásárhely became thicker, their forms became more static, and their texture also changed due to the casting compound different from that of Herend.

Interestingly, the award-winning Bella service of the Varia competition was only placed on the market in 1975 under the name Bella-207, while the Saturnus—with the form number 208 in Alföld Porcelain Factory—was first released in 1977-1978. There were plenty of technological problems with it even after the alteration, as most of the service’s items had an outward bending brim, which often deformed during firing, thus they could only manufacture it with a high scrap ratio. The first-class items were typically sent for export, while Hungarian consumers received the second and third-class sets. Not too many households in Hungary had a complete set with all the pieces—with more than thirty different functions. It is also noteworthy how while the Bella-207 set often received rather loud decorative stickers not matching in style, which heavily outweighed the beauty of the forms, in the case of the Saturnus set, they only used subdued decoration: a golden or platinum streak to accentuate the brims or the dandelion, a recurring motif in Horváth’s oeuvre. Most often—in line with the intentions of the designer—the pieces were left undecorated, allowing the noble qualities of the forms and the material to come to the spotlight.

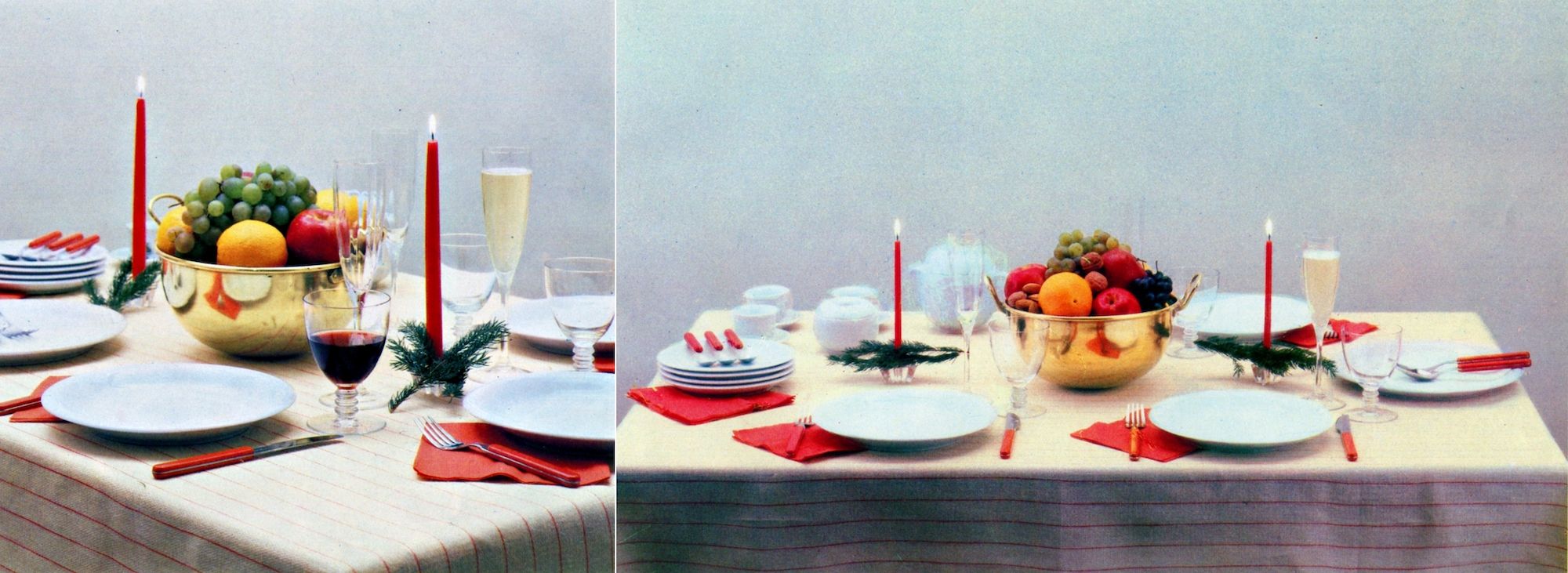

The publication A szépen terített asztal (The Well Set Table) edited by József Vadas[9] showcased commercially available products related to dining culture on colorful interior photos. The volume used the Saturnus most frequently and at the most diverse festive occasions—always highlighting that its versatile use was owing to its classic, clean forms and white, undecorated pieces.

To me, the forms of the Saturnus set can be interpreted as a late projection of the Space Race during the Cold War: I envision a Moon Capsule or space shuttle designed by NASA engineers in the sophisticated, snow-white soup bowl, and the ring system of the planet Saturn into the arched brims of the dinner plates and soup dishes. As told by László Horváth, others rather compared his objects to the shape of whitewashed beehive ovens, the forms of which he actually used as an inspiration in the course of designing his set. After his success in Faenza, his master, Imre Schrammel shared the opinion of his foreign colleagues with him, according to whom it did not reflect either Scandinavian or Italian aesthetic or the influences of the Rosenthal factory, it rather had something inexplicable, something exotic, a sort of Hungarian feel to it.[10]

József Vadas considers the Saturnus set László Horváth’s “enchantingly elegant”[11] masterpiece, which is also one of the most painfully sabotaged opportunity in Hungarian design culture. Usually there’s little point in asking questions starting with “what if…”, but this time perhaps we should stop for a minute and ask ourselves: what if the Saturnus set had been put into production at the Herend Porcelain Factory, which pursued a significant export activity at the time? What if in Faenza, in 1973, the product had been represented and managed both from a professional and economic aspect, or if they had sold its designs to an interested company beyond the Iron Curtain?

These are thought-provoking questions and there are even more of them if we take a look into the catalogues of the National Silicate Industrial Triennials organized four times between 1979 and 1988, in which we can find objects that also existed only on a prototype level almost exclusively, out of which many could have been known and recognized across the world had they made it into production. In the first and third catalogue of the triennials held in Kecskemét, László Horváth also appears with the Hólabda (Snowball) and Delta services—perhaps the latter could even competes with the qualities of the Saturnus.

The Varia competition was announced 50 years ago, thus the Saturnus set was born almost half a century ago. Its shapes have become an integral part of Hungarian object culture, many people are still looking for them, using them and collecting them today. This is where its name starts to truly make sense, because its pieces are modern, advanced and ageless even today—time, or rather Saturn, doesn’t seem to affect them. Emblematic objects from a designer who keeps creating today: Horváth manufactured his lamp design titled Mandula in Herend Porcelain Manufactory in 2019.[12]

In his poster series titled Hype forms, graphic designer László Bárdos pays homage to Hungarian design icons and their designers, including László Horváth and the Saturnus set—the 3-piece Hype forms series is available for sale in HYPEANDHYPER’s online store.

[1] SEBALD, Winfried Georg (2011): A Szaturnusz gyűrűi. Angliai zarándokút. Translated by Éva Blaschtik, Budapest: Európa Könyvkiadó. [Die Ringe des Saturn. Eine englische Wallfahrt. 1995.]

[2] See for example:

VADAS József (1980): Herend gyűrűjében. A Saturnus készlet története. In Kritika. 1980/5, pp 21-22

VADAS József (1985): A Saturnus bolyongása. In Nem mindennapi tárgyaink. Budapest: Szépirodalmi Könyvkiadó, pp 162-172

VADAS József (2008): Elitdesign vagy stílporcelán. Herend válaszúton. In Ha majd a szépnek asztalánál. Mindennapi design. Budapest: Jószöveg Műhely Kiadó. pp 60-68. [Kritika. 2000/8, pp 29-31.]

[3] D.N. (NikolettDárday) (1972): Porcelán- és üvegpályázat. In Ipari Művészet. 1972/4, pp 16-18

[4] Today known as Herendi Porcelánmanufaktúra Zrt.

[5] József Vadas quotes the statement of engineer-economist Dr. Béla Felek, the director of Herend Porcelain Factory at the time, which was originally published in Népszabadság’s issue released on May 12, 1970 in the article titled Az öreg Herend és a feltámadt Városlőd:

VADAS József (1985): A Saturnus bolyongása. In Nem mindennapi tárgyaink. Budapest: Szépirodalmi Könyvkiadó, pp 163-164

[6] Telephone interview with porcelain designer László Horváth on December 1, 2020.

[7] The porcelain sheets made with the lithophane technology are reliefs made with a cast technology, playing with the light-transmitting ability of the material. The plasticity of the scene or the portrait depicted becomes visible when lit from the back, depending on the thickness of the material. The technique mainly gained popularity in the 19th century and was used for decorating candle and fireplace shades, lampshades and sometimes dishes.

[8] Hopefully we can give a more detailed report of this significant design history event in relation to the design curator specialization of Moholy-Nagy University of Art and Design.

[9] VADAS József (ed.) (1986): A szépen terített asztal.Budapest: OMFB – Office of the Applied Design Council.

[10] Telephone interview with porcelain designer László Horváth on December 1, 2020.

[11] VADAS József (1985): 163.

[12] I would like to express my gratitude for the help provided for writing this article to: László Horváth, Lászlóné Horváth, Zsombor Horváth and Kitti Mayer.

In our Object Fetish article series, we introduce the emblematic pieces of Hungarian object culture. We go after objects and their designers: we ask questions, we investigate and we learn. A four-hand piece by design theorists Kitti Mayer and Piroska Novák, published every two months.

In partnership with:

From houseboats to quantum-coffins | STORQUE

Opening to the land | Fránek Architects