Marek Locher is a Polish documentary photographer, who has been documenting Silesian mines for a long time. We asked him about how he started photographing, why he chose the Silesian landscape and the mine as a subject, how he interacts with the miners, and how difficult it is to work down in the mine.

How and why did you get into photography?

It was at the beginning of the 2000s. I picked up a camera because I felt the need to document the Silesian landscape, which was changing a lot due to the transformation of the political system. In the 1990s, there was a major restructuring of heavy industry, including the liquidation of the mines that had been part of my landscape since childhood.

How and why did you start photographing miners? How long have you been doing it?

I’m a graduate of a technical school for mining, but I never worked a single day in the mines. Nevertheless, the impulse to photograph them was the aforementioned liquidation process. My first conscious collaboration with a large mining company started in 2008.

Silesia is famous for its mining tradition. What is the situation of mining in the region today?

In Upper Silesia, coal mining has been greatly reduced since the 1990s. For example, of the eight mines of the company I started photographing for in 2008, only two are currently active. The company itself has already been taken over by another company, and this gives an idea of the extent to which this industry is being reduced in Silesia. There are currently 14 thermal coal mines operating in the region, and they will also be closed by the middle of the century. There are also 6 mines producing coking coal, which is a strategic raw material.

How do the miners react to you taking pictures of them and going down the mine with them?

Because I know the industry, I usually know what and how I want to photograph. This helps a lot in establishing a conversation with the crew because we often discuss professional topics. People feel more comfortable and are more willing to pose in front of the camera. I also use Silesian, which I know because I was born in Upper Silesia. This is also a reason to “understand each other better” and to trust the photographer.

There is no natural light down in the mine, and it can be dangerous. How difficult is it to work down there?

High humidity, high temperatures, dust, and of course the risk of gas explosions and rock falls... Anything can happen, so this is no job for the faint-hearted! While the extraction work itself is highly mechanized, the various preparation and transportation tasks can be very difficult. What counts is the close cooperation of the crew. This makes the whole plant work like a healthy organism. Traditionally, a miner is wished for as many trips to the surface as descents.

The medium of photography has been associated with mining since its invention but has received little attention. What is your objective with this series?

To document, archive, and preserve what I find interesting, essential, and original. I simply love Silesian mining, the architecture, the specificity of the place, and the people I meet.

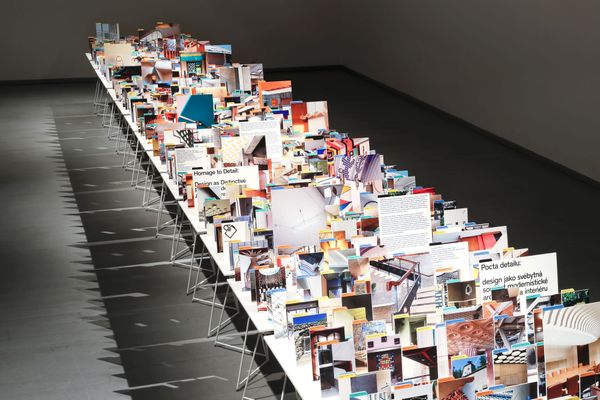

What are your future plans with the photos; showing them in exhibitions or making a photo book?

Yes, I do have exhibitions from time to time, but they are only temporary events. However, the most memorable thing would be to publish my own photo book. I’m thinking about it, and for now, it’s just a matter of considering... Probably because I still have the desire and the ability to add new mining images to my collection. Time will tell where this ends up.

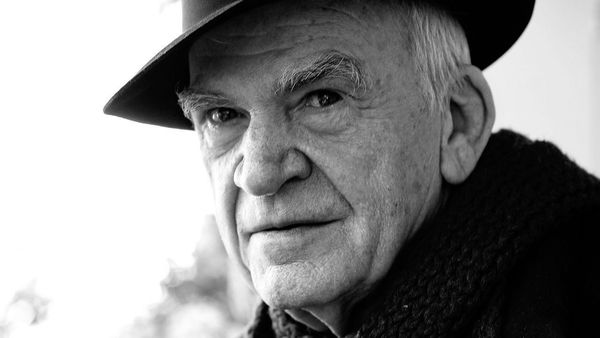

Milan Kundera passed away

Natural materials, combinable basic pieces | selera