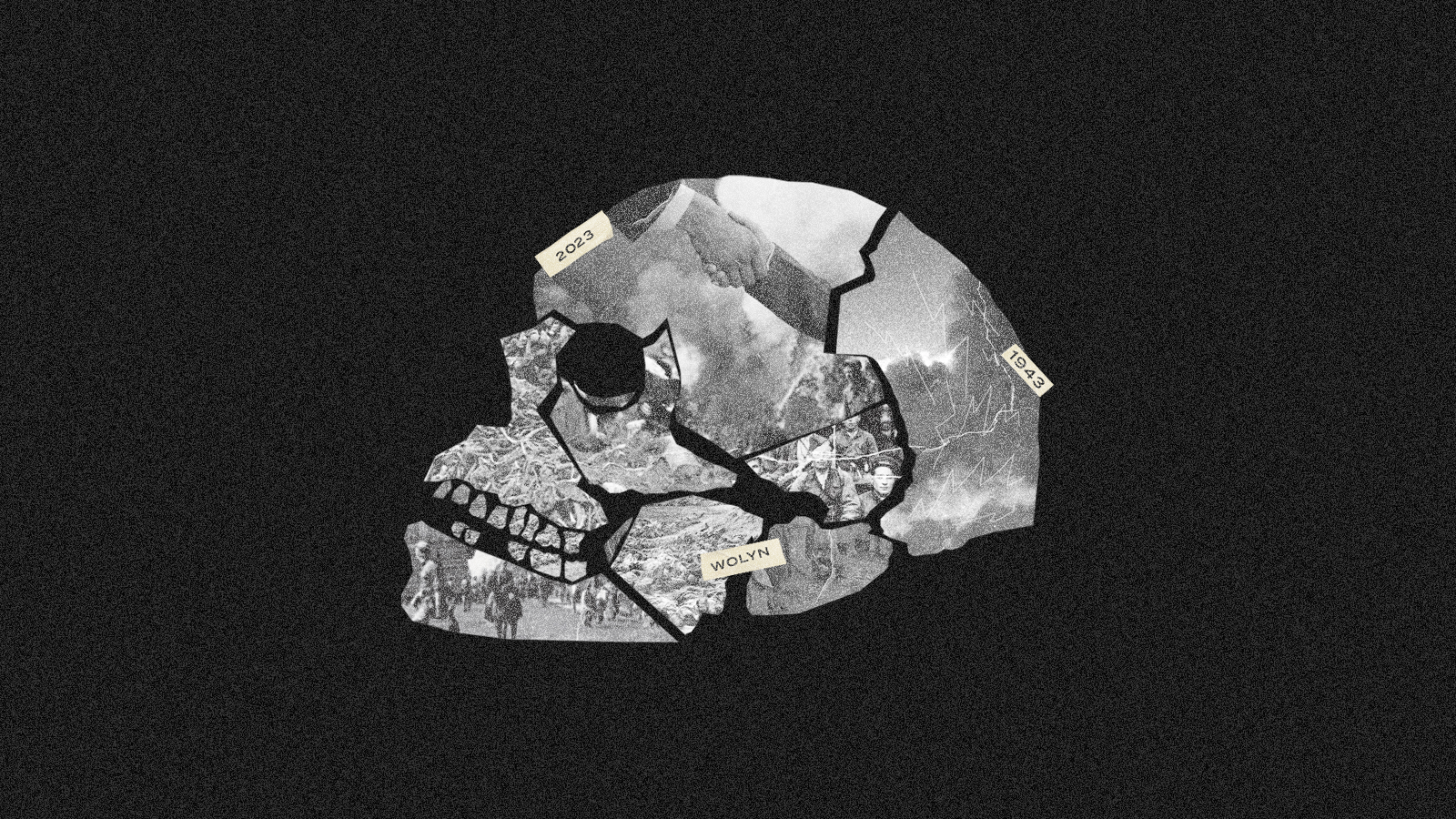

July 11, 2023, marks the eightieth anniversary of the Volhynia massacre – a horrific event in which the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA) murdered around 100,000 Polish civilians. Polish President Andrzej Duda and Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky jointly commemorated the massacre. While the Ukrainian President’s stand is significant, this blot on the two countries’ shared history is still a source of tension between them.

The once anti-Soviet and anti-Nazi, nationalist Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA) carried out brutal atrocities in the villages of Volhynia and Eastern Galicia in German-occupied Poland between 1943 and 1945. The events culminated in July 1943, and Poland established 11 July as a day to commemorate the horrific events. Around 80,000 Poles were murdered at that time, but the massacre series could have had up to 100,000 victims, and some believe the number could be double that. The victims were civilians, most of them children and women. The reason behind the massacre was presumably to prevent a post-war set-up in which a possible sovereign Polish state would emerge in the partly Ukrainian-inhabited territories.

Although the joint commemoration by Zelensky and Duda on the eightieth anniversary was symbolic and showed the unconditional commitment of the Ukrainian President, the tragedy of the Volhynia massacre casts a shadow over the alliance between the two countries. The Polish government, the leaders of the Catholic Church, and the vast majority of Polish society believe that the massacre was undoubtedly a genocide, and the lower house of the Polish parliament, the Sejm declared this in 2016 with no votes against it. But on the Ukrainian side, the situation is not that clear: Petro Poroshenko, the Ukrainian President in power in 2016, said on Facebook that he „regretted” the Sejm’s decision and quoted former Polish Pope John Paul II’s commandment for forgiving and asking for forgiveness. Poroshenko may also fear Russia would use Warsaw’s decision against Ukraine for political gain. In 2016 this issue was particularly sensitive as Warsaw has for many years assured its eastern neighbor of its support both in EU integration ambitions and in the face of Russian aggression. So Kyiv’s reluctance to use the term „genocide” was a major setback in the good relations between the two allies.

The view on the nationalist partisan UPA’s ethnic cleansing during World War II divides Ukrainians on both political and social levels. The issue is particularly sensitive as Ukrainian society tends to see the rebel formation’s actions with a certain exaltation as they were fighting against oppressive forces. Thus, the recognition of the cruel activities against the Polish civilians would be painful, meaning facing the not-so-heroic reality. Nevertheless, some Ukrainian intellectuals have no problem calling the massacre in Volhynia genocide. One example is Yaroslav Hrytsak, a prominent Ukrainian historian, who declared the UPA’s actions „genocide against Poles.”

Now that the Russian invasion of Ukraine is entering its eighteenth month, the Ukrainian perception of the massacre is being put in a new and quite remarkable perspective. Poland has been a staunch supporter of Ukraine since the beginning of the war, but this does not mean that the trauma of the massacre stopped depressing the Polish nation. Poles want the event to be declared genocide and wish the exhumation of the victims followed by their reburial with dignity. Although President Zelensky seems to be more willing to engage in these efforts than his predecessors, the tension is far from being resolved. In March, news started to circulate that Ukrainian President Zelensky had promised Polish Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki that the victims of the massacre would be exhumed. „They have promised that the exhumation will finally go ahead,” said Morawiecki, adding that „the truth about the massacres in Volhynia must be clarified.” He also said that „We will not let this topic go, regardless of what is happening in Ukraine now.” Zelensky, already at the beginning of his presidency, in 2020, together with Polish President Andrzej Duda, expressed his hope for „respect for historical truth,” which includes the exhumation of the victims. But the process could only begin in November 2022 as the Ukrainian authorities blocked its launch before. The authorization of exhumation in November was seen as a step forward in Polish-Ukrainian relations. Polish Deputy Foreign Minister Marcin Przydacz said that „this is a big change compared to the way the Ukrainian authorities have approached the situation before” and added that it was „a very good step in the right direction, which shows that consistent dialogue and cooperation can make it possible to overcome even such difficult decisions.” Regarding the exhumations, Andrii Deshchytsia, former Ambassador of Ukraine to Poland, said that local politicians often hinder the exhumations but added that „his opinion is that we should pay tribute to the deceased and bury them in a Christian way.”

While this move was certainly a source of some optimism, there have since been events that have further increased tensions, such as the Ukrainian Institute of National Remembrance (UINR) reticence to exhume the victims’ remains. The UINR’s position is that the exhumation of Polish victims can proceed only if the damaged Ukrainian military graves on Polish territory are restored and protected in the future. The soldiers of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army were buried in these graves, whom the Poles murdered in retaliation for the massacre in Volhynia. According to the Head of the UINR, the Polish authorities have shown no willingness to cooperate, and there is a lack of reciprocity. „Until they are restored, we cannot give permission for another exhumation of Poles buried in Ukraine because Ukrainian graves in Poland remain at risk,” said Anton Drobovych, head of the Ukrainian Institute of National Remembrance. This stance has provoked strong negative feelings in Poland, particularly because the UINR considered the massacre in Volhynia, where civilians, mostly children and women, died, to be the same severity as the subsequent revenge where soldiers who committed the massacre were killed in far fewer numbers. Paweł Jabłoński, Deputy Foreign Minister of Poland, called Drobovych’s position „unwise, inappropriate and damaging to Polish-Ukrainian relations.” The Polish politician also said that while Kyiv is very keen on joining the European Union, „it is hard to imagine that this issue will not be resolved before Ukraine joins the EU.” So, the Poles see a Ukrainian EU accession justified only with the condition that Kyiv can deal with their shared history in appropriate terms.

Moreover, in May this year, regarding the eightieth anniversary of the massacre, Polish Foreign Ministry spokesman Łukasz Janisa said that while it is clear that Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky is now the head of state of a country at war, he should still take more responsibility for the massacre in Volhynia, including an apology. He added that he believes that Ukrainians have little understanding of the significance of the massacre but hopes that the eightieth anniversary can lead to change. But his statements have angered the Ukrainian side. Ukraine’s ambassador to Poland, Vasyl Zvarych, in an emotional Twitter post that he later deleted, called such and similar requests to Ukraine’s president unacceptable, adding that Ukraine remembers the common history but “calls for respect and balance in statements, especially given the complex reality of the genocidal Russian aggression against the Ukrainian people.” But he later replaced this with a more moderate tweet, stressing that they understood the importance of history and respected the memory of the victims.

During last year’s 79th anniversary, a few months after the start of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Polish Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki pointed out that the Russo-Ukrainian war was an opportunity to calm the strained Ukrainian-Polish relationship over the massacre. Morawiecki drew parallels between the atrocities committed by Ukrainian nationalists during World War II and Russia’s invasion, identifying the Ukrainian Insurgent Army, which committed the massacre, with the „Russian world.” „When Ukraine heroically took up arms, when Poland helped Ukraine, when we opened our homes to Ukrainian refugees... we have an opportunity to overcome centuries of hatred and resentment, an opportunity we cannot lose because posterity will not forgive us,” Morawiecki said on last year’s anniversary. Polish President Andrzej Duda then stressed that the search for historical truth for Poles is not about revenge but about reconciliation.

So the conflict has not been completely resolved, but the joint commemoration by the Ukrainian and Polish presidents is undoubtedly significant in easing tensions between the two countries. On 9 July, the two heads of state lit a candle in a church in the Ukrainian city of Lutsk. Also, as part of the commemoration of the eightieth anniversary, the head of the Polish Catholic Church, Stanisław Gądecki, and the head of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church, Sviatoslav Shevchuk, held a ceremony in Warsaw on 7 July. The two archbishops jointly signed a statement saying that „Russia’s aggression against Ukraine makes us realize that reconciliation and cooperation between our nations is a necessary condition for peace in this part of Europe.” The Polish Church leader stressed the importance of calling the event a genocide publicly „instead of a tragedy, ethnic cleansing or a crime.” Gądecki also warned Ukrainians against glorifying Ukrainian nationalists. The Ukrainian Church leader also emphasized the necessity of „forgiveness and apology.” But whether this can ever actually happen between the two countries without all the strife and recriminations is hard to tell.

Graphics by Roland Molnár

Architect Petr Janda launches new project in Prague