Dubbed Datapolis, the new business engaged in data analysis functions as a bridge between academic life and the business sector. As there are representatives of both fields in their team, a continuous dialogue is formed: this dynamic is what differentiates Datapolis from other data mining companies operating in the field of urbanism amongst others, and as a result, they can offer focused answers to the partners’ questions that can be easily followed by real steps. And these steps may even lead us to more livable and sustainable cities.

“How do physicists end up on the field of urbanism?” – a question that Milán Janosov, a team member of Datapolis gets quite frequently. He is the Chief Data Scientist of the company, and as such, represents the academic community in the team together with László Barabási-Albert. “The answer to this question goes back to the start of an open dialogue between natural sciences and human sciences. Data analysts often coming from the field of mathematics or physics started to examine and test theories and hypotheses through many newly available and large-scale data sources that are heavily originating in social sciences, but can only be measured and verified authentically on the level of the population with various quantitative methods, such as the toolset of statistical physics.“

This dialogue has been going on for almost twenty years in BarabásiLab. Datapolis is a step towards incorporating these academic researches, methods and quantitative models into business solutions. This is not your average data analytics-consultant company, but a specific product, which “can help in issues of urban development, location selection or location evaluation as a product that scales well on the global market” – explains Datapolis CEO Balázs Szima-Mármarosi.

How was Datapolis’s team and the concept formed?

Balázs: The teams of Gergely Böszörményi-Nagy and Albert-László Barabás worked together on an adaptive urban development project earlier. Datapolis was launched owing to the excellent relationship formed in the course of this project, focusing on developing a tool that can answer questions of urban development, investment-related questions, questions of location evaluation for the business sector and questions related to moving and tourism for the population as a packaged product. Milán and I joined earlier this year, Milán as a Chief Data Scientist and I as a CEO, while Emese Décsi joined the project from the field of urbanism.

How is Datapolis different from data-based consulting companies and how should we imagine the product itself?

Balázs: A consulting company can only take on as many jobs as many experts there are in its team. In opposition, in the case of a packaged product virtually anyone can work with a city whose data we have already mapped and processed.

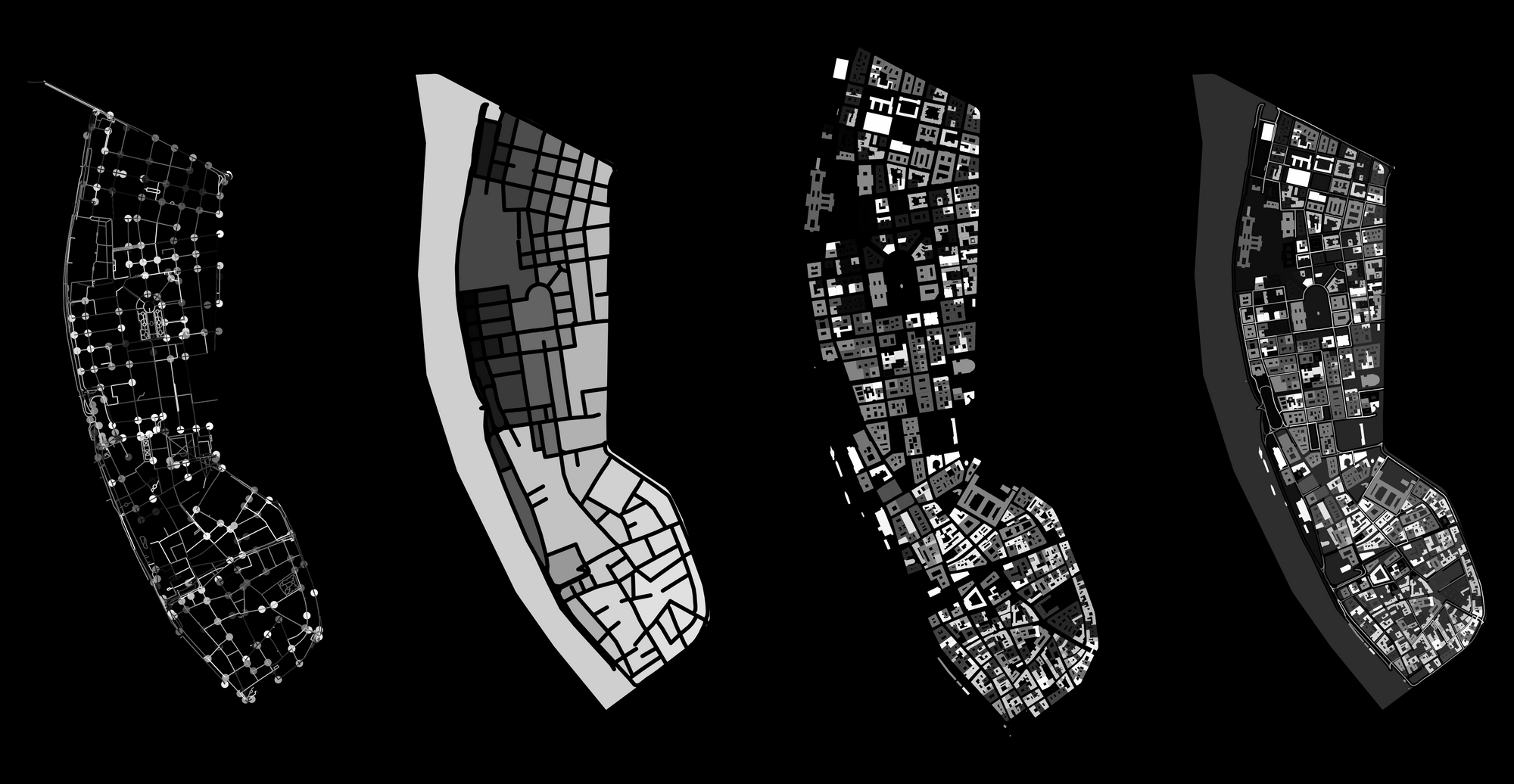

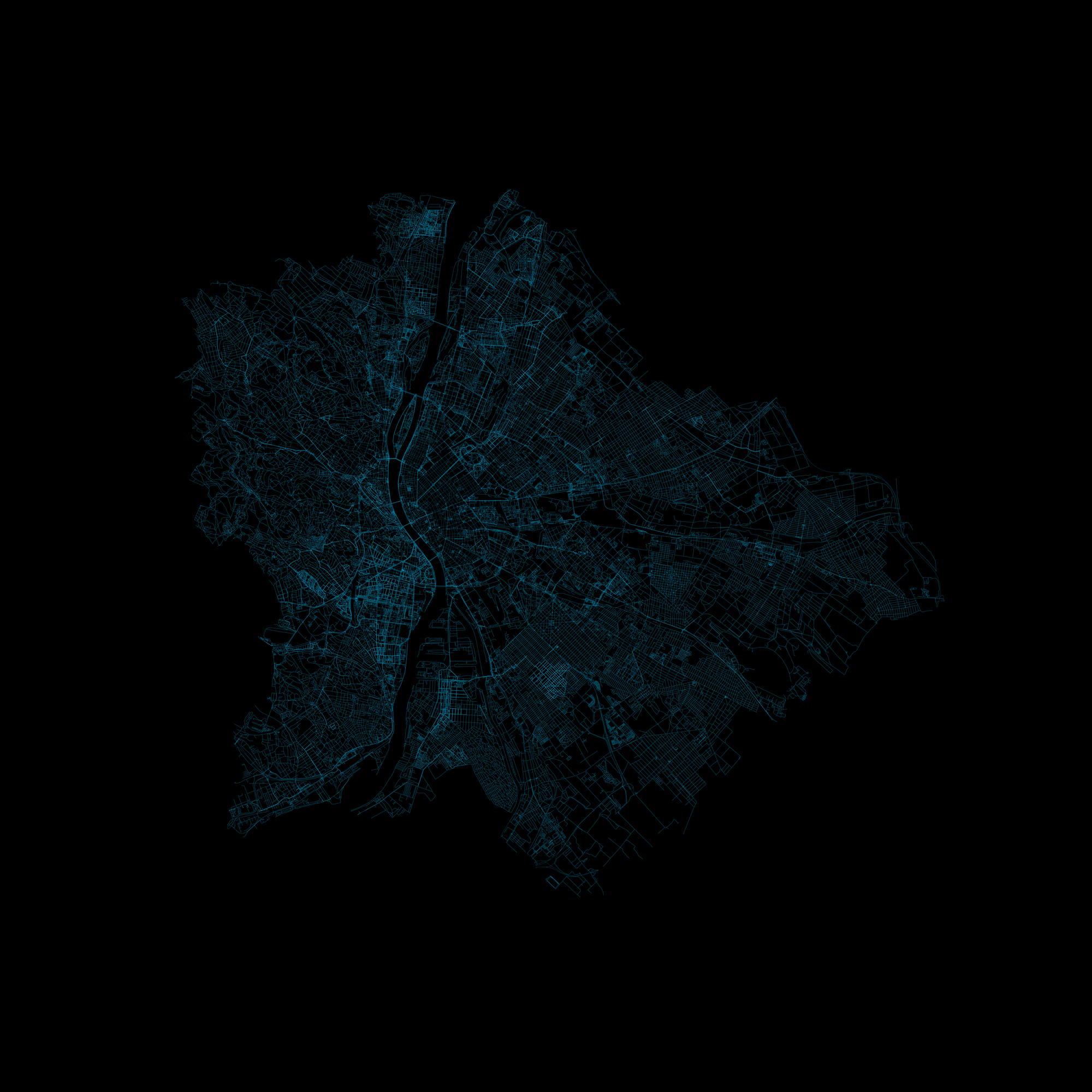

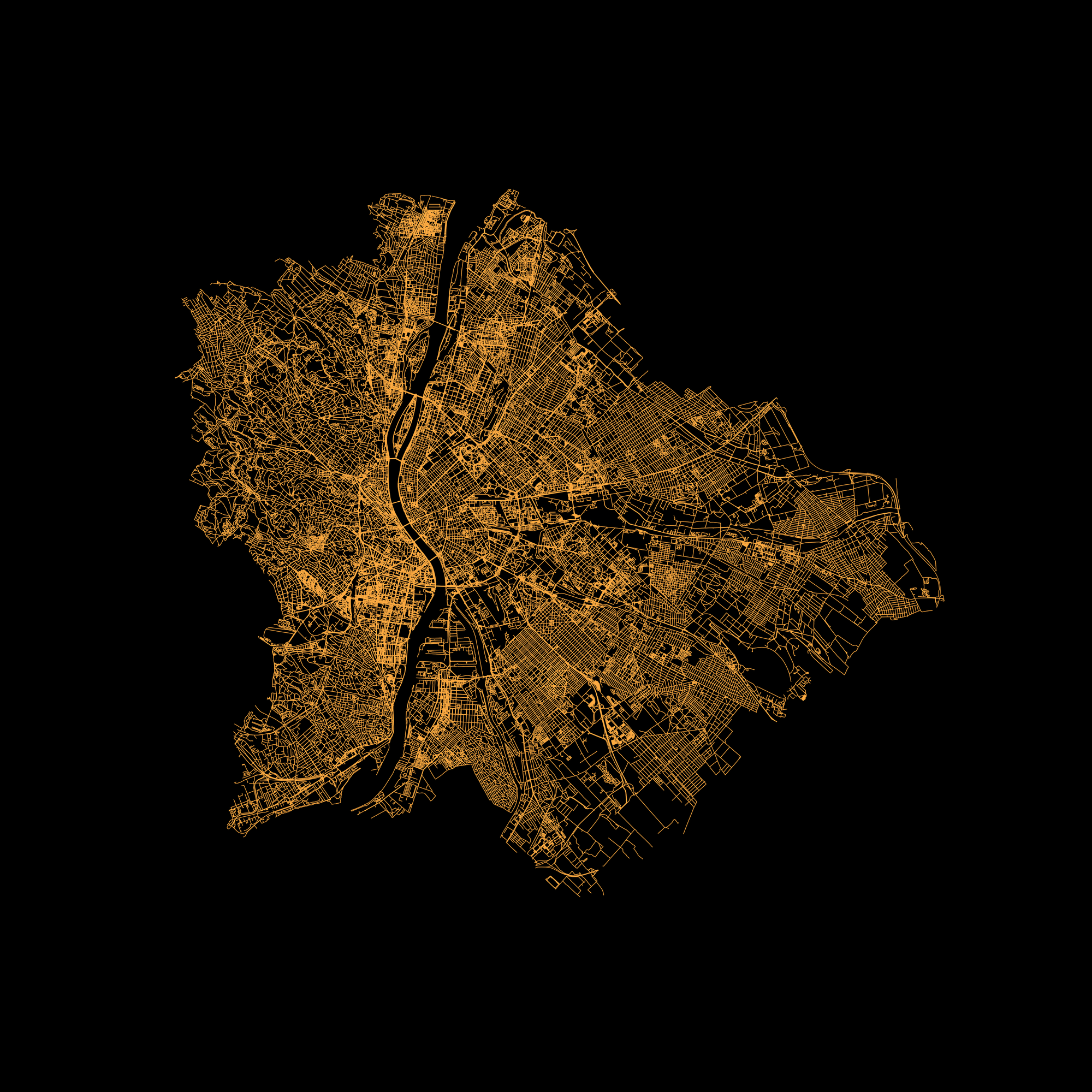

We focus on the general understanding of the behavior patterns of cities and the people living in them and on answering business questions based on the same. These can be questions asked by a governmental or state officer: for example, what kind of infrastructural changes are needed in order to improve the public safety of a district, or to reduce its car traffic? On this level, we can help by answering the questions of how a neighborhood can be made more livable, where a new park should be built or how a public transportation system should be reorganized.

This already gives a quite broad spectrum, and we haven’t even talked about business clients.

Balázs: Yes, and one of the greatest challenges of the project is how not to get lost in the beauty of data even when we can give answers to questions of incredible quantity and quality by understanding people’s behavior based on the data.

Our job is not to answer all the questions. We are looking for a focus for building a global product, this is why we chose the business sector, where the same questions arise in every entity, starting from restaurant chains, through shopping centers, gas stations or bank network companies: where should they put their next unit, or what kind of product selection should they offer in the existing locations? These questions concern everyone in this sector, but up until now the possibilities of data analysis were fairly limited. Of course there are big location-data analytics companies in the world that collect data about mobility: what we offer as a plus, and this is where Milán and Laci come into the picture, is that we not only examine this data in themselves, but also where the network of people in the given target audience is moving.

Let’s stick to one of the examples you mentioned. Could you outline what happens when for example a gas station network contacts you and says that they would like to better utilize the potential of their existing units?

Balázs: Let’s assume that based on the data we see that 10% of the guests entering the station later go into a grocery store to do a 15-minute shopping. In this case, the owner of the gas station can think about adding fresh bakery products, vegetables etc. to their selection. How a location can be utilized the most is an interesting question.

We believe that a business that knows and understands the needs and preferences of its customers can achieve a double-digit increase in revenue, and we can also verify this with numbers.

Data mining companies give rise to privacy concerns in many, and they also raise the question of how the data obtained is turned into useable information.

Balázs: It’s important to stress that the data that we receive are not individual data, we see masses and aggregates. Big companies that sell data, including Telekom or Mastercard comply with the legal framework, and do not disclose personal data.

The real challenge is not to obtain data, as it can be bought for money – it is what you do with the data once you have it. I think this is where our added value comes from: we work with people who achieved many things over the past years and decades and who built models that create information out of the data.

How often should the database be updated? As a result of the Covid-19, for example, people must have formed completely new habits that change the previous picture for sure.

Milán: This primarily depends on what data sources you mean. Population for example should not be updated on a daily basis obviously, but mobility could be updated per hours or even minutes especially if there are mass events and restrictions.

Balázs: That’s right. The visitor component of a given neighborhood will not change from Monday to Tuesday, but in a 3-month interval it should be reviewed, especially in extreme cases, like the situation brought on the by epidemic.

How did the epidemic affect your project? What phenomena resulting from Covid-19 have already seen?

Balázs: The coronavirus has changed habits and behaviors fundamentally. It forced the services sector to reinvent the relationship with its potential customers and to discover who these potential customers are. The changing habits and requirements also brought new opportunities: areas and neighborhoods that were “dormant quarters” previously could suddenly turn into flourishing districts. Another phenomenon observed during the quarantine was that as a result of people ordering food, books, groceries, etc. via home delivery, the importance of urban logistics increased.

Milán: It’s as if we got back to square one – we have to rethink a lot of models concerning human behavior and the life of cities built until now, which offers many new opportunities.

Balázs: Yes, and a great example of this is subcentralization, which is an important aspect from the perspective of the livability and sustainability of cities. This has accelerated significantly nowadays.

We have arrived to the question of urban development: what role could Datapolis have in it? Have you received any enquiries from the city administration yet?

Balázs: I think city leaders who understand the value of data will sooner or later work with us or companies with a similar profile. For us, it is not only an opportunity but a responsibility to help city administrations in the spaces we live in. We have already worked on projects of the kind and it seems there is an increasing interest towards us both on a Hungarian and international level from the side of city administration and urban development, too.

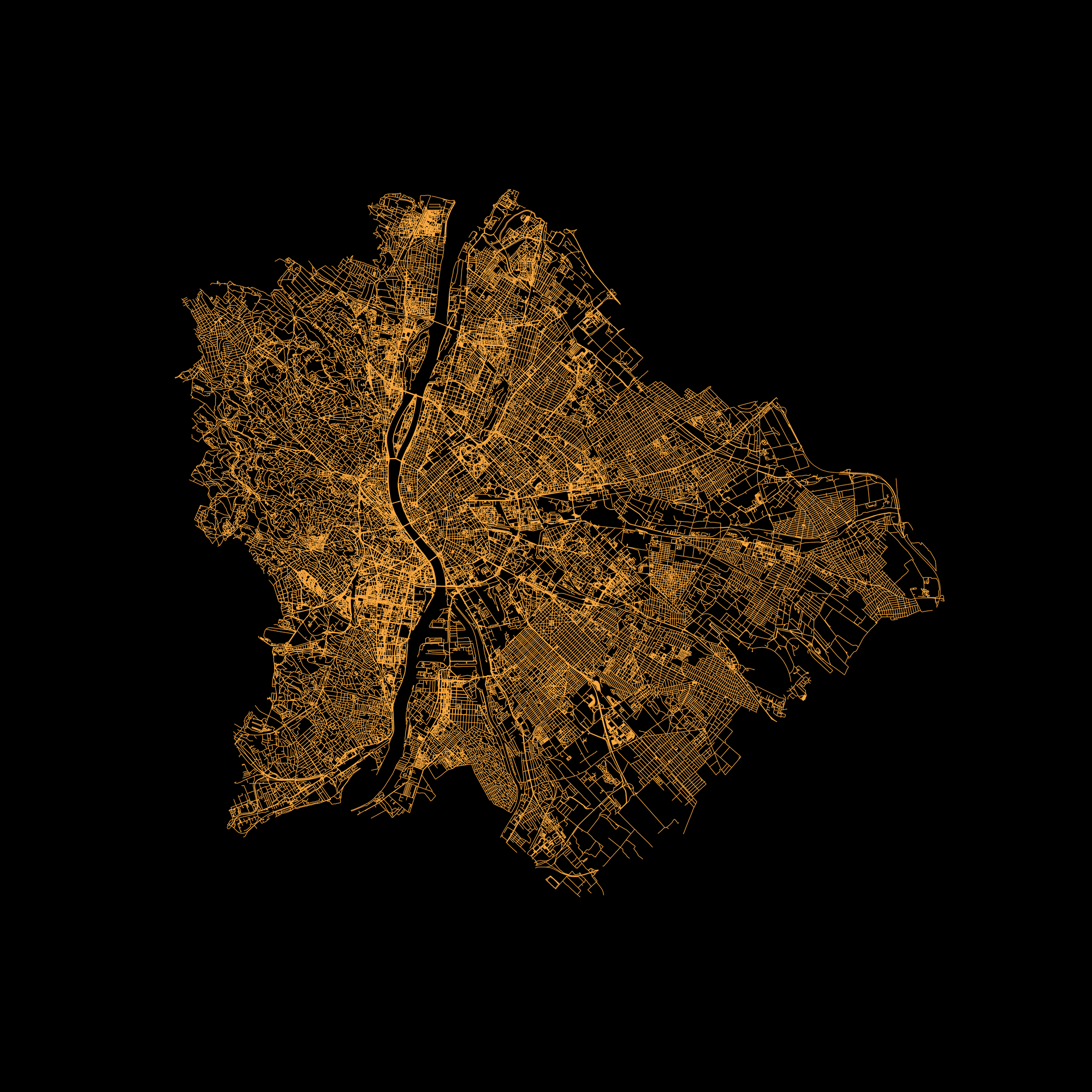

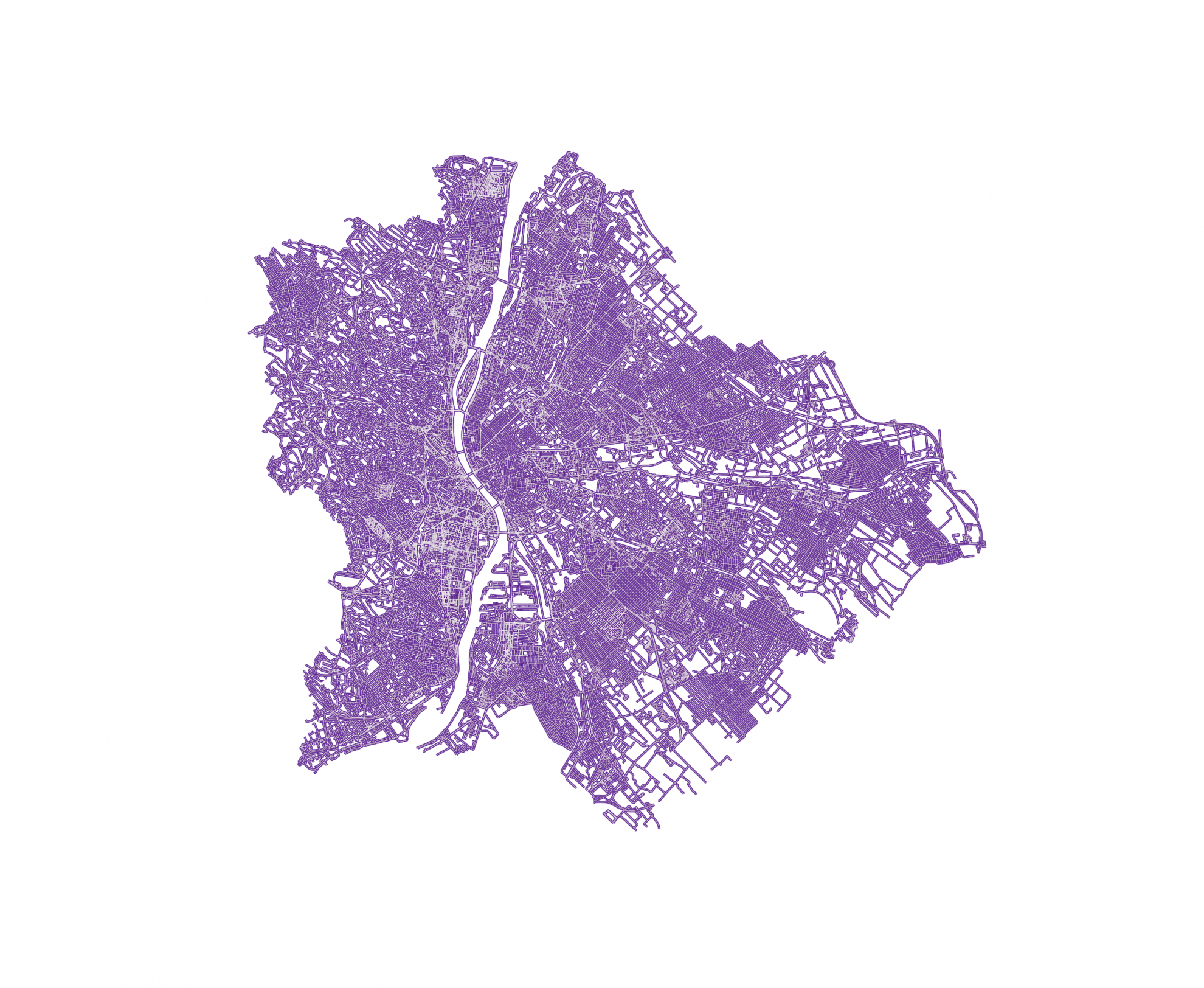

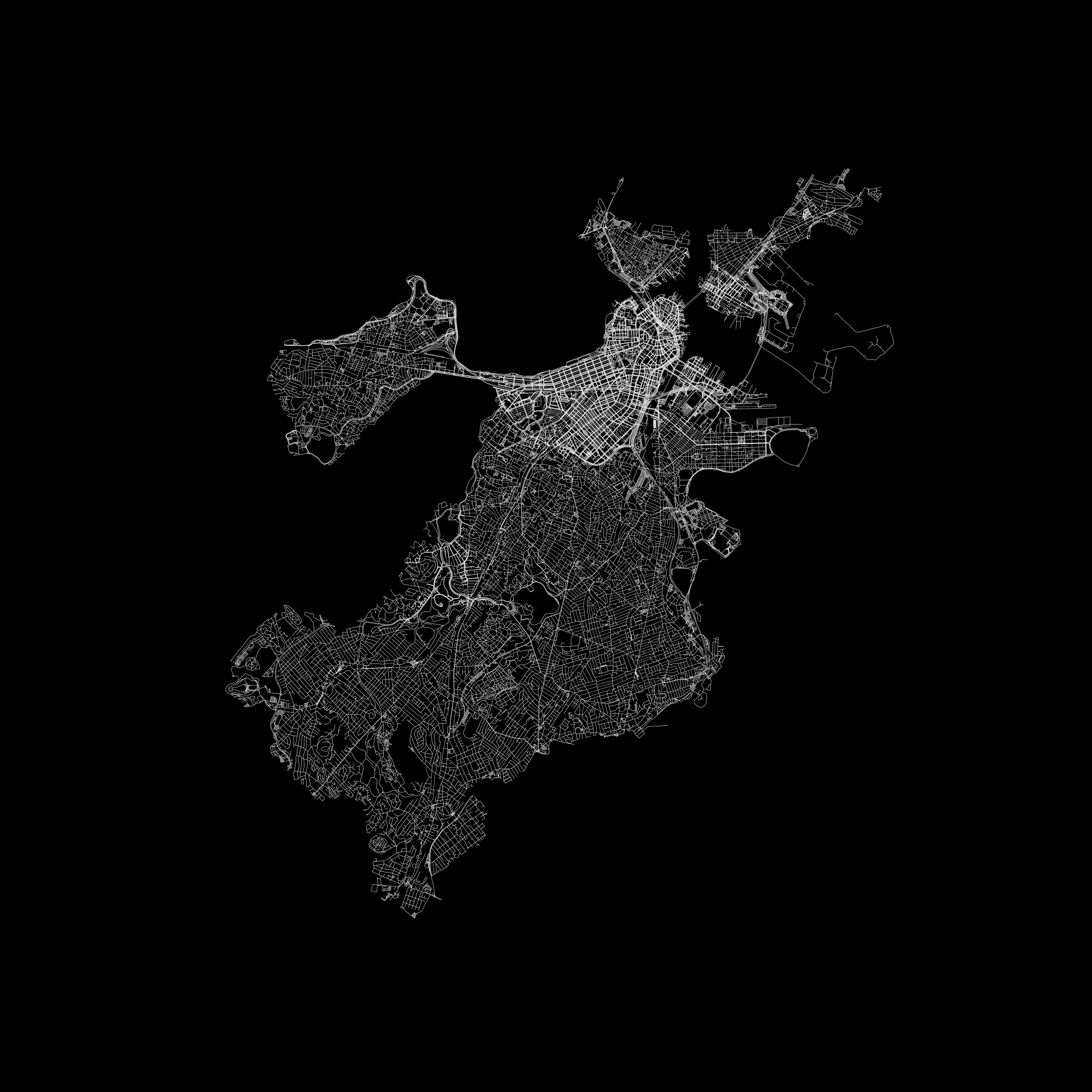

We would also like to interpret the city as a grid, as a social fabric. Milán Janosov

Milán: Many times it turns out that it is the characteristics of this underlying network that define whether a city will become a well-functioning or malfunctioning entity.

The same thing applies to the network between people: if everyone only meets a few people, then only small, micro-communities will be formed, where the flow of ideas and information will not be that creative. At the same time it is also not beneficial if a city forms a single community because it ends diversity, and the creative potential also decreases. We must find a balance between the two directions, which is possible through the establishment of park centers at good locations and the smart organization of transportation between them, through adequate cultural facilities, all in all via conscious and data-driven urban planning.

So far all signs point to us being able to find the network optimum in a complex system which can make our cities even more livable than they are at the moment from the point of both people and businesses.

Datapolis | Web

Atari is back