Jelena Jureša’s art unfolds in the fragile space between history and silence, between what is remembered and what is deliberately erased. Born in the former Yugoslavia and now based in Belgium, she has built a practice that interrogates the ways power and violence shape collective memory, while questioning who gets to narrate the past. Through film essays, installations, photography, and performance, Jureša challenges audiences to confront complicity and trauma not as distant events, but as living structures that continue to shape our present.

Born in the former Yugoslavia, currently based in Belgium, Jelena Jureša is a deeply engaged visual artist and filmmaker whose work operates at the intersection of memory, identity, violence, and the politics of forgetting. Her multi-layered practice includes film essays, video installations, photography, text and performance, all of which she deploys to challenge dominant historical narratives and to intervene in what we collectively choose to remember — or to silence. At the heart of Jureša’s work lies a sustained inquiry into how power, complicity, trauma and erasure operate in both personal and collective spheres. She often frames her explorations through the lens of spectral absence — investigating what is left out of official histories — and the difficulty of “speaking” or “representing” violence when it resists conventional narrative forms. Themes such as gender, cultural identity, colonialism, nationalism, and collective guilt or silence surface repeatedly in her projects.

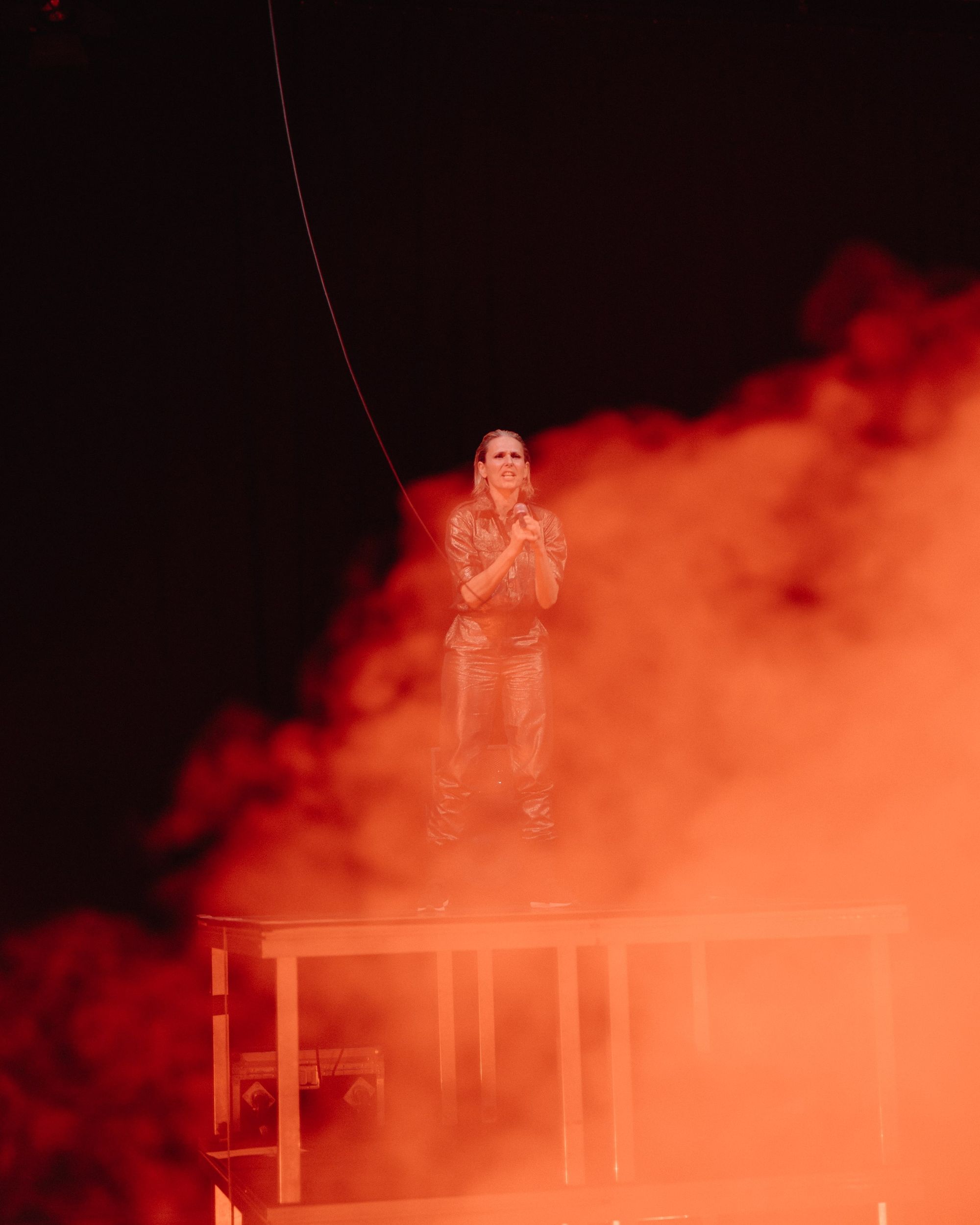

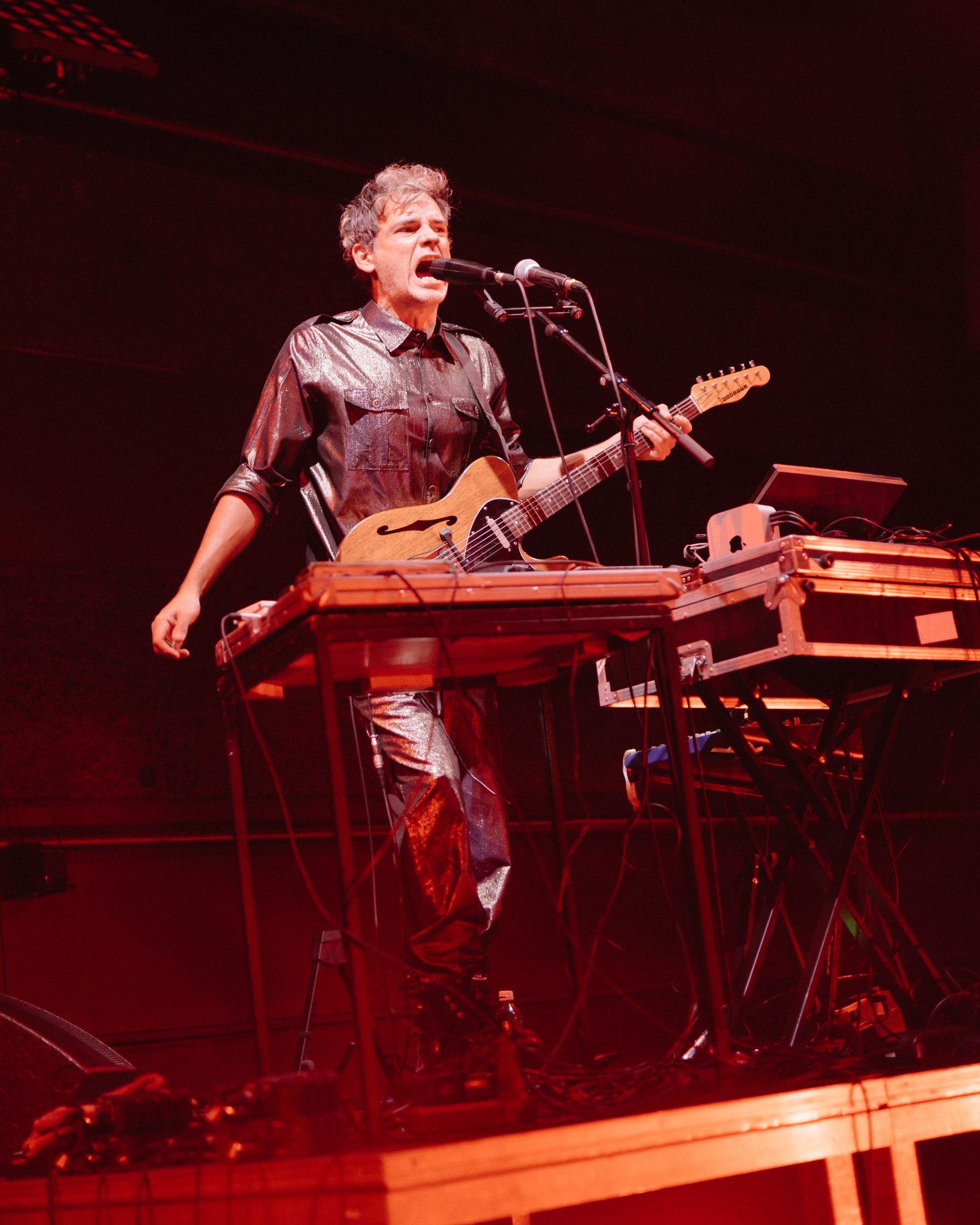

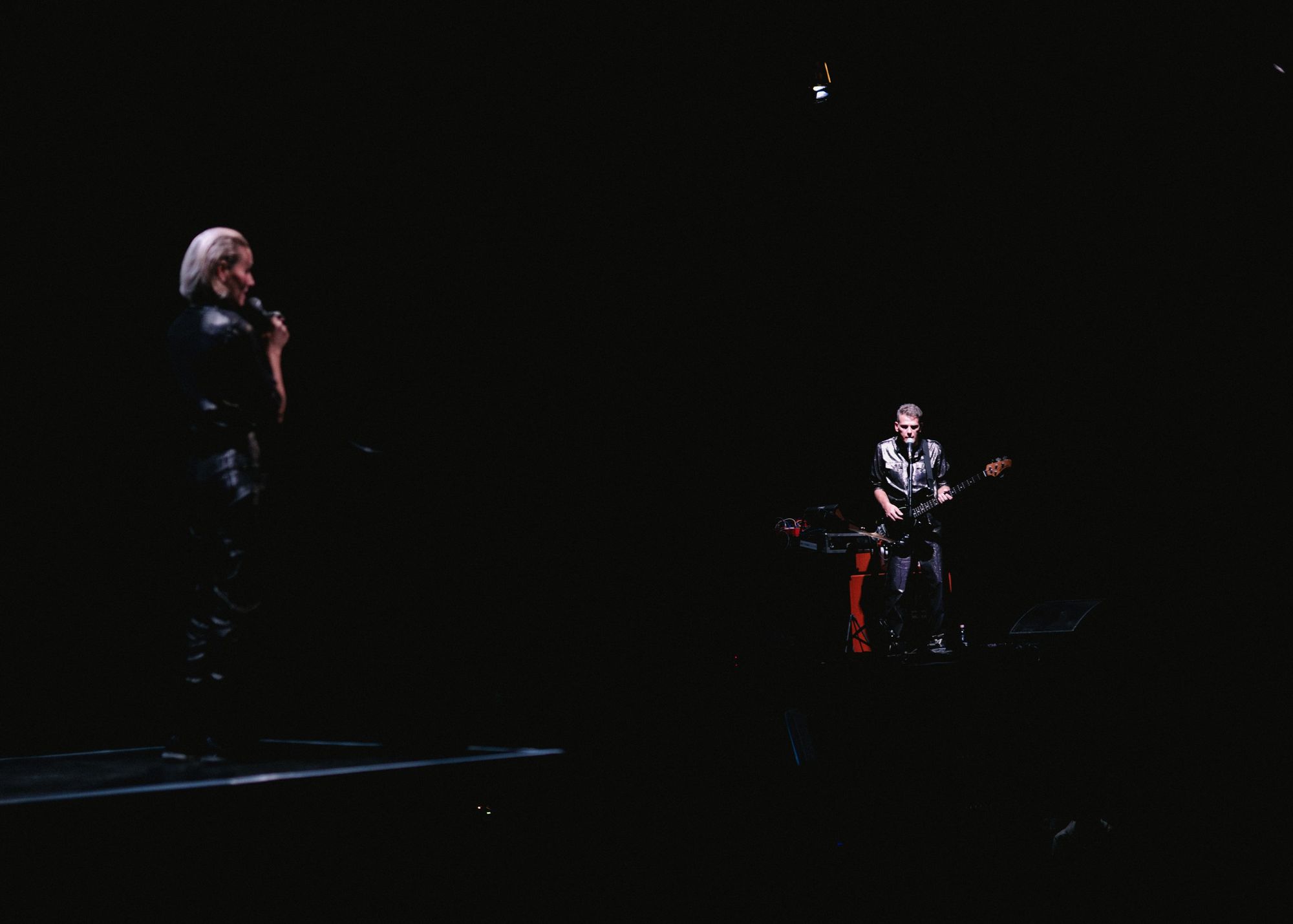

Jureša’s signature project is Aphasia, a film-essay and installation in three chapters that threads together narratives of Belgian colonial violence, Austrian racial experiments, and atrocities committed in the Bosnian war. In Aphasia, she asks: how do we find a language for collective silence, for crimes that persist in the shadows? From the film she developed an immersive concert-performance version in which a war photograph from Bosnia is reactivated in a club environment, collapsing witnessing and complicity, past and present. She came to Budapest at the end of September when the performance version of Aphasia was presented in Budapest as part of Trafó’s The End of Violence series.

What inspired you to become a visual artist?

It was simply an interest I had since childhood. But the real pull towards the medium came later, through the topics I wanted to explore. For me, film lies on a thin line between other art forms — I see it more as a combination of mediums. Even when the final outcome of a project is a moving image, the research process often involves dramaturgical thinking through performance, photography, or text.

When did you move from Serbia to Belgium, and how did it affect your identity as an artist?

I moved to Belgium 11 years ago on a PhD scholarship, but, in truth, what mattered most was keeping my son away from the cycle of political violence in Serbia. That decision shaped how I reflect on many things today. I was born in Yugoslavia, and then lived in Serbia after its dissolution — so in a way, I changed countries without ever moving. Serbia was involved in war and perpetration, and the question of complicity was very present within me. Arriving to Belgium meant that I also became "the other." This shift deeply influenced how I understood identity, belonging, and the politics of perspective.

How did you come to work with issues of memory, forgetting, and collective violence?

Above all, it was my experience of living in Serbia during the proxy wars the country led. Still, it took me time to find a way to translate those experiences into the language of film. I am not interested in simply recounting events — I’m more drawn to the question of what it means to narrate. Who is speaking? Who gets to tell the story, and to whom? The gendered dimension of narration also matters to me — who is given authority as a storyteller? I’ve also been fascinated by collective denial, and how it operates in different systems, such as in imperial Europe. Anecdotes often interest me too, because they occupy an outsider’s place in relation to official historiography. Sometimes an anecdote can reveal blind spots more effectively than an “official” account.

How do you think about the role of the audience — as listeners, participants, or witnesses?

I mostly work in gallery contexts, with video installations. There, I always consider the positioning: how the work will be set up in space, where the audience will stand, what they will see, and how they will relate to it. That also influences how I think about the camera and the production of the work. I don’t usually work in theater as part of my artistic practice — the concert-performance Aphasia, now presented in Budapest, is actually my only live-audience work. I developed it from the earlier film Aphasia because I felt there were questions I couldn’t answer in the film alone. The performance was created in collaboration with musicians Alen and Nenad Sinkauz and dancer Ivana Jozic, and the piece really emerged from that collective process. The audience’s role here is partly participatory, but it also leaves them a lot of freedom. I always start from trusting the audience — I never want to over-explain. In this work, narration isn’t central; you actually learn much more through the music.

What does the title Aphasia mean to you? How does this concept relate to the politics of language, listening, and memory?

Aphasia means the loss of speech, the inability to translate your thoughts into language. The title came after I read an essay by Ann Laura Stoler, where she spoke about “colonial aphasia” in the context of French colonialism. I found it to be a powerful way of thinking about historical denial — not as collective amnesia, which suggests forgetting, but rather as an inability to translate knowledge into speech. We are aware of what happened, we know it, but we lack the language to articulate it.

Do you think it is possible to “cure” social amnesia through art, or should absence and silence be made visible as such?

It’s a difficult question. We are all complicit or implicated in our shared histories. As artists, we are also political subjects, and when we have the possibility to speak about something, we make a choice about how we want to participate in public discourse. I often doubt what artist can actually do — I don’t think I can change much. But I can choose to voice what matters to me. At the same time, I think it’s important not to take oneself too seriously.

How have different audiences reacted to the project — in Belgium, Austria, or the Balkans?

I wouldn't say audiences have different expectations, but their readings of the work do shift a bit. In Belgium, for example, people are not very informed about the wars in Yugoslavia — it feels distant, almost absent from public awareness as if it never took place in Europe. In Germany and Austria, the reception differs in the way that historical fascism and its references are more readily recognized. The work hasn't been shown in any ex-Yugoslav country, and it still cannot be shown in Serbia. In the work, I reference a member of the Serb Volunteer Guard, known as Arkan's Tigers. No one from that paramilitary unit has been brought to justice.

What other mediums would you like to explore? Where do you see further opportunities to push the boundaries of genre?

I seek to push boundaries from within the medium I am working in. With every project, I ask myself: what should I do next, how can I turn things on its head to critically engage with the problematics of inherited gaze? The process itself makes me mature as an artist. I grow together with the work — and that growth keeps me moving forward.

Opening photo: Bea Borgers