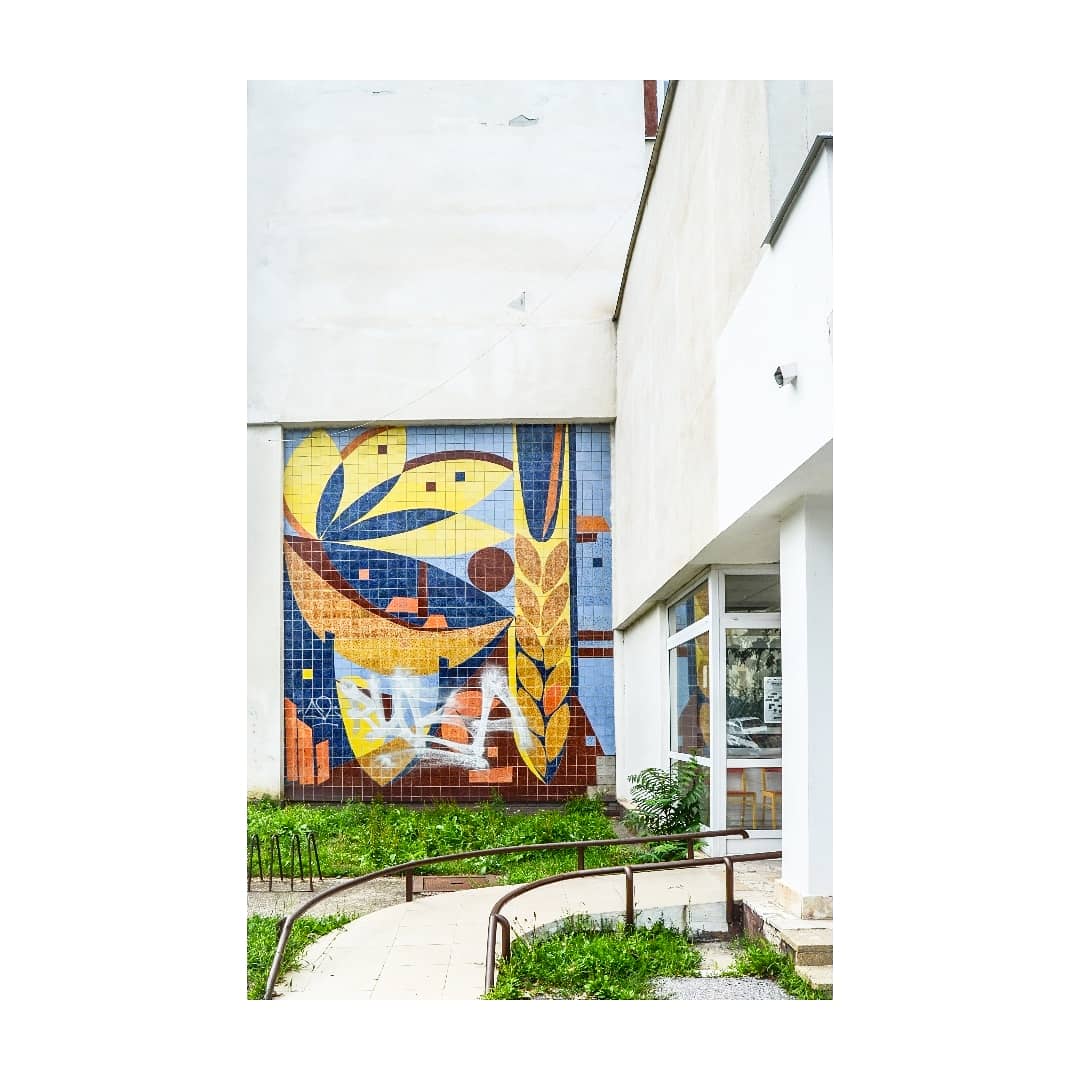

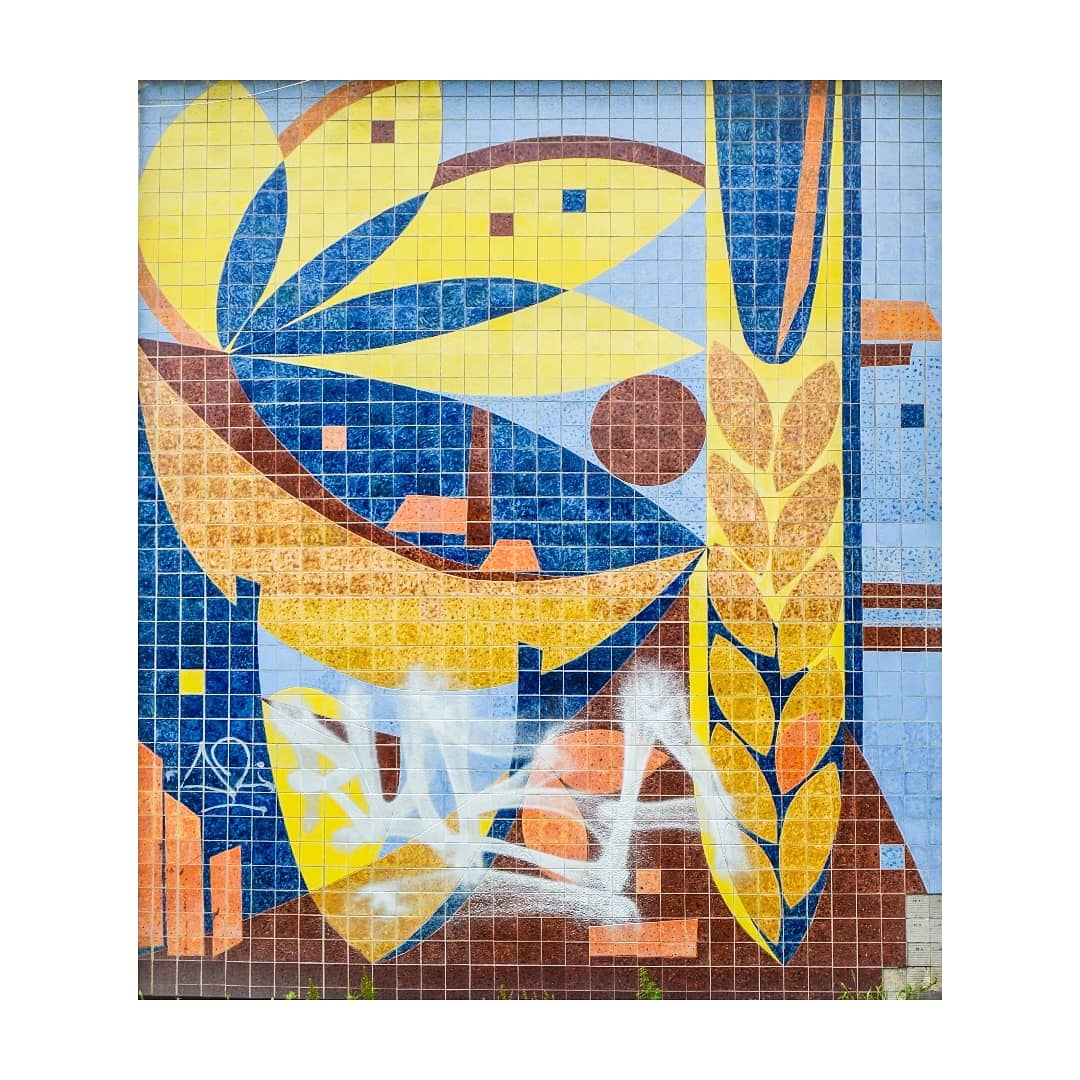

Mátyás Zagiba launched an Instagram account with the name LEN HLINA, or “Clay Only” to promote the unfairly forgotten building-decorating ceramics.

Mátyás Zagiba, a second-year ceramics student at MOME, came to Budapest from Jovice, a Slovakian village with barely eight hundred inhabitants. In March of this year, during the pandemic, he began systematically processing the monumental ceramic works left on the façades or interiors of various public institutions. To not just work for the account, he launched an Instagram page called LEN HLINA (Clay Only), promoting this unfairly overlooked genre. Building-decorating ceramics have suffered the same fate in our northern neighbors as in Hungary. Why?

Due to its genre specialties, monumental ceramics cover several areas at once: architecture, fine arts and applied arts meet in these works. There is architecture because it appears as an integral part of the building (on the exterior façade, interior wall), fine art because it conveys the message of one (or more) artists, and applied art, as it uses an unusual raw material, ceramics, to communicate the message you want to express. This genre diversity—where we could mention sculpture and urbanism in addition to those listed—makes the building-decorating ceramics fall behind: it belongs to several genres, but in fact, nowhere. While (ideally) such works attract a larger audience, they, as “peers” in the visual arts, appeal to the townspeople themselves and await visitors within the walls of museums. However, the layman is usually hardly aware of the presence of these monumental works of art—at best, we note the ornate, colorful wall surfaces for better orientation, but we know much less about their creator, the circumstances of their making.

By creating the LEN HLINA page, Mátyás wants to change that: to show the beauty and value of this genre for as long as possible. After all, in most cases—precisely because of the unprocessed nature of the subject, the lack of canonization—these works are demolished and destroyed during the reconstruction of the building, and at most such works remain in the form of archival recordings.

The account was launched in March 2021 and mainly collects building-decorating sculptures made during the period of normalization, that is, between 1969 and 1989. Monumental ceramics attracted Mátyás’ attention already in high school, and he first visited Košice and its surroundings with open eyes. In Rožňava, on the wall of the former post office building, a sculpture made by Lýdia Čepková (born: Mészárosová) stood out in front of him, which also included the artist’s signature and the date of its making.

Lýdia Mészárosová studied at Otto Eckert’s workshop at the Academy of the Arts, Architecture and Design in Prague and met her future husband, Milán Čepek, who both worked for a short time at the porcelain factory in Brezova and moved to Košice in the 1960s.

Several monumental ceramics can be found in Rožňava: the façade of the train station is decorated with the work of Milán Čepek, and the abstract geometric mural of Ádám Szentpétery, born in Rožňava in 1986, can be seen on the wall of the marriage hall.

One of the most exciting discoveries of Mátyás was the case when he managed to identify the work of Imrich Vanek on a deserted field in Plešivec, based on a Facebook post of Čierne diery. The scattered pieces of the composition, made in 1978 and now in a rather dilapidated state, were donated to the Slovak Design Museum to save what could be saved.

In the absence of a signature and year, the research should start with the artists’ monographs or various archives, as at the moment we, unfortunately, do not know of an online database that would collect such building-decorating ceramics—in the Czech Republic the vetrelciavolavky.cz website deals with public works of art and in Hungary, the köztérkép.hu. This Czech page can be of help to those interested in the topic, as there are some examples of the territory of the former historical Hungary, a few works by Imrich Vanek from Košice can also be found here. However, monographs do not always help, because although Imrich Vanek, Miloš Balgavý, or Juraj Marth, born in Komárno, and his colleagues are recognized artists, rather their autonomous work has been processed, and there is less talk about monumental ceramics.

Mátyás was the first to aim to map the region of Eastern Slovakia, but later, if his duties allowed, he would extend the research to the whole of Slovakia, and it would be suggested that he even process the topic in the form of a thesis, giving word to the surviving artists.

Nature and technology merge together in the new Burberry installation

Hungarian talent attracted great interest in Dubai